Volume 16, Issue 6 (November & December 2025)

BCN 2025, 16(6): 1159-1168 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Haghani M, Namavar M R, Dehghani F, Vatanparast J, Naseh Z, Kokhdan S P et al . Sodium Valproate Mitigates Hippocampal Structural and Functional Alterations Following Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion in a Rat Model. BCN 2025; 16 (6) :1159-1168

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3165-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3165-en.html

Masoud Haghani1

, Mohammad Reza Namavar2

, Mohammad Reza Namavar2

, Farzaneh Dehghani3

, Farzaneh Dehghani3

, Jafar Vatanparast4

, Jafar Vatanparast4

, Zahra Naseh5

, Zahra Naseh5

, Samira Panahi Kokhdan6

, Samira Panahi Kokhdan6

, Maryam Naseh *7

, Maryam Naseh *7

, Mohammad Reza Namavar2

, Mohammad Reza Namavar2

, Farzaneh Dehghani3

, Farzaneh Dehghani3

, Jafar Vatanparast4

, Jafar Vatanparast4

, Zahra Naseh5

, Zahra Naseh5

, Samira Panahi Kokhdan6

, Samira Panahi Kokhdan6

, Maryam Naseh *7

, Maryam Naseh *7

1- Histomorphometry and Stereology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. & Department of Physiology, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

2- Histomorphometry and Stereology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. & Department of Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. & Clinical Neurology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

3- Histomorphometry and Stereology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. & Department of Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

4- Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

5- Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Center for Transfusion Medicine and Cellular Therapies, School of Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, United States.

6- Department of Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

7- Histomorphometry and Stereology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

2- Histomorphometry and Stereology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. & Department of Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. & Clinical Neurology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

3- Histomorphometry and Stereology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. & Department of Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

4- Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

5- Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Center for Transfusion Medicine and Cellular Therapies, School of Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, United States.

6- Department of Anatomical Sciences, School of Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

7- Histomorphometry and Stereology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1630 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

Introduction

Brain ischemia is one of the most prevalent cerebrovascular diseases and is the second contributor to global morbidity and mortality. Cerebral ischemia can occur when blood flow to a part of the brain is temporarily restricted because of embolism, thrombosis, or systemic hypoperfusion, and then blood flow is restored to the affected areas, which is called reperfusion. The pathological mechanisms of ischemia-reperfusion injury include oxidative stress, inflammation, excitotoxicity, and the complement system, which lead to necrosis and apoptosis in the ischemic area (Jiang et al., 2022). These destructive events can ultimately cause neurological deficits and behavioral dysfunctions (Deb et al., 2010). After reperfusion, oxygen and glucose re-enter the brain, further challenging the ischemic tissue. Oxidative glycolysis of glucose yields substantial amounts of the reduced cofactors nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2), and during electron transfer, superoxide anion (O2−) is generated, contributing to the buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (Nishi et al., 2005). The excessive generation of oxidative free radicals promotes lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, nitrification, and DNA and mitochondrial damage (Beckman, 1996). Additionally, ROS and RNS cause leukocyte recruitment, chemokine and inflammatory mediator production, impairment of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), and the consequent cerebral edema (del Zoppo & Mabuchi, 2003). Currently, mechanical thrombectomy and intravenous thrombolysis are the primary therapies for ischemic stroke; nevertheless, each method has its own set of restrictions. Therefore, to overcome these problems, researchers need to identify new neuroprotective agents for the treatment of ischemic stroke.

Sodium valproate (VPA) is widely utilized to treat neurological diseases, including bipolar disorder and seizures, and can also be used as a new strategy for treating ischemic stroke (Johannessen, 2000). It has been shown that VPA can have protective effects against animal models of ischemic stroke by increasing antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities reducing the production of oxidative metabolites, as well as its capacity to restrain histolysis (HDAC) and suppress glycogen synthase kinase 3 (Chen et al., 2014; Pang et al., 2016; Shao et al., 2005; Silva et al., 2018). Similarly, the antioxidant activity of VPA has been investigated in vitro, and it has been suggested that the mechanism of VPA can be through the inhibition of glutamate-induced neurotoxicity, disturbances in intracellular calcium homeostasis, DNA fragmentation, protein oxidation, and lipid peroxidation (Kanai et al., 2004; Rekling, 2003).

In a previous study, we examined the effects of VPA on synaptic plasticity and memory function impairments in a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model (Naseh et al., 2022). Building on the previous study, this research investigated the spatial organization of pyramidal neurons, the three-dimensional structure of the hippocampal CA1 region, and oxidative stress changes in MCAO rats. Studying possible microanatomical changes in the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons after MCAO is an excellent opportunity to better explain brain dysfunction after stroke. Furthermore, in studies related to cerebral ischemia, most researchers have focused on neuronal quantity (Moralí et al., 2005), with comparatively little attention paid to the spatial organization of neurons or to the three-dimensional structure of CA1 region, which may critically influence functional recovery. Therefore, we decided to assess the impact of VPA on the spatial arrangement and three-dimensional structure of the CA1 pyramidal neurons in an experimental MCAO model.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Thirty male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–250 g, 6–8 weeks old) were obtained from the Center of Comparative and Experimental Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Animals were housed under controlled conditions (21±2 °C; 12 h light/ 12 h dark cycle) with free access to food and water. The experimental procedure was approved by the Committee for the Ethics of Scientific Research of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, and all procedures complied with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Experimental groups

The rats were randomly assigned to three groups: Sham, MCAO, and MCAO + VPA (n=10 in each group).

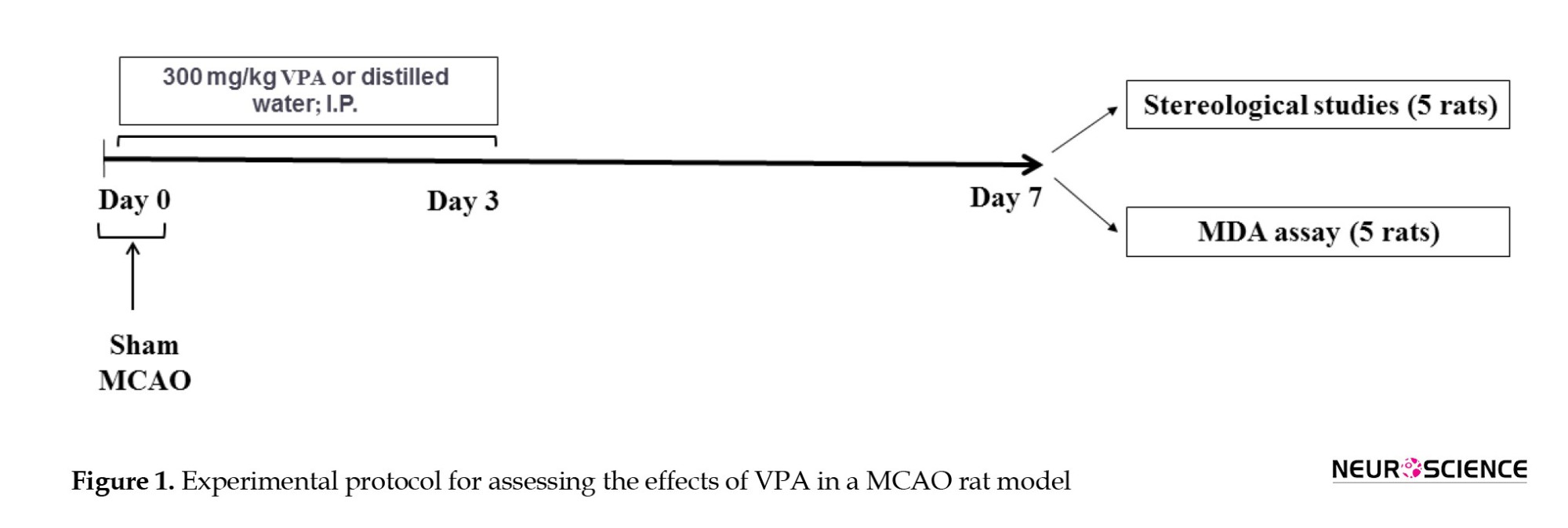

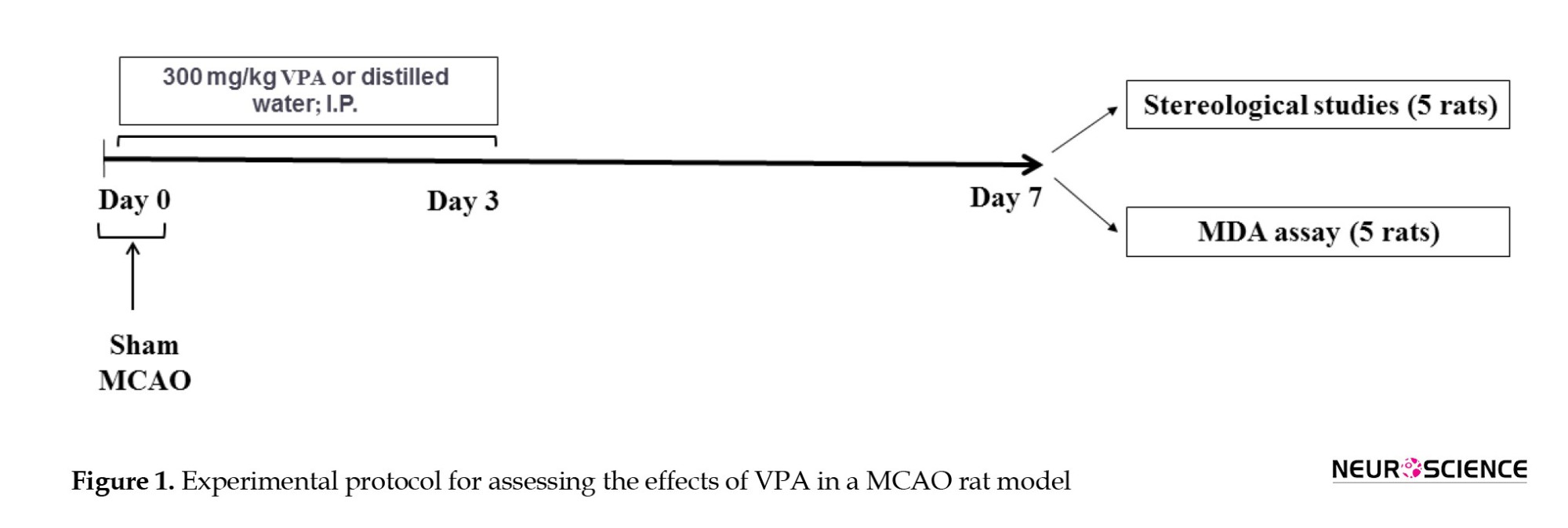

The MCAO model was established as described in our previous studies (Naseh et al., 2022; Naseh et al., 2020). Briefly, the rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal (IP) injection of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Then, the right common carotid and external carotid arteries (ECA) were exposed. A silicone-coated monofilament suture (4043PK5Re, Doccol, USA) was introduced to the external carotid artery (ECA) and advanced through the internal carotid artery (ICA) to occlude the middle cerebral artery (MCA) for an hour. The suture was subsequently removed, allowing reperfusion. Notably, the body temperature of rats was controlled by a rectal thermometer. Sham surgery was performed similar to the MCAO protocol except without inserting a monofilament into the ICA. VPA (300 mg/kg (Mann Brukner et al., 2018; Naseh et al., 2022; Xuan et al., 2012); Merck, Germany) was solubilized in 300 μL distilled water, and injected IP on days 0, 1, 2, and 3 post-MCAO (Figure 1). Intraperitoneal administration was chosen to ensure accurate dosing and to avoid the stress associated with oral gavage.

One week after MCAO, the brains (ischemic hemisphere) of five animals were removed and preserved in 10% buffered formaldehyde for a week. The brains were then placed in 30% sucrose solution for three days and stored at -80 °C until further analysis (stereological study). Additionally, the brains (ischemic hemisphere) of five other rats were removed and kept at -80 °C until biochemical evaluations.

Stereological assessment

The ischemic hemisphere of the brain was coronally and serially sectioned at 50 μm thickness using a cryostat (Microm HM 525, Germany) and stained with cresyl violet. The CA1 hippocampal region was identified according to the Paxinos and Watson Atlas (Paxinos & Watson, 2007).

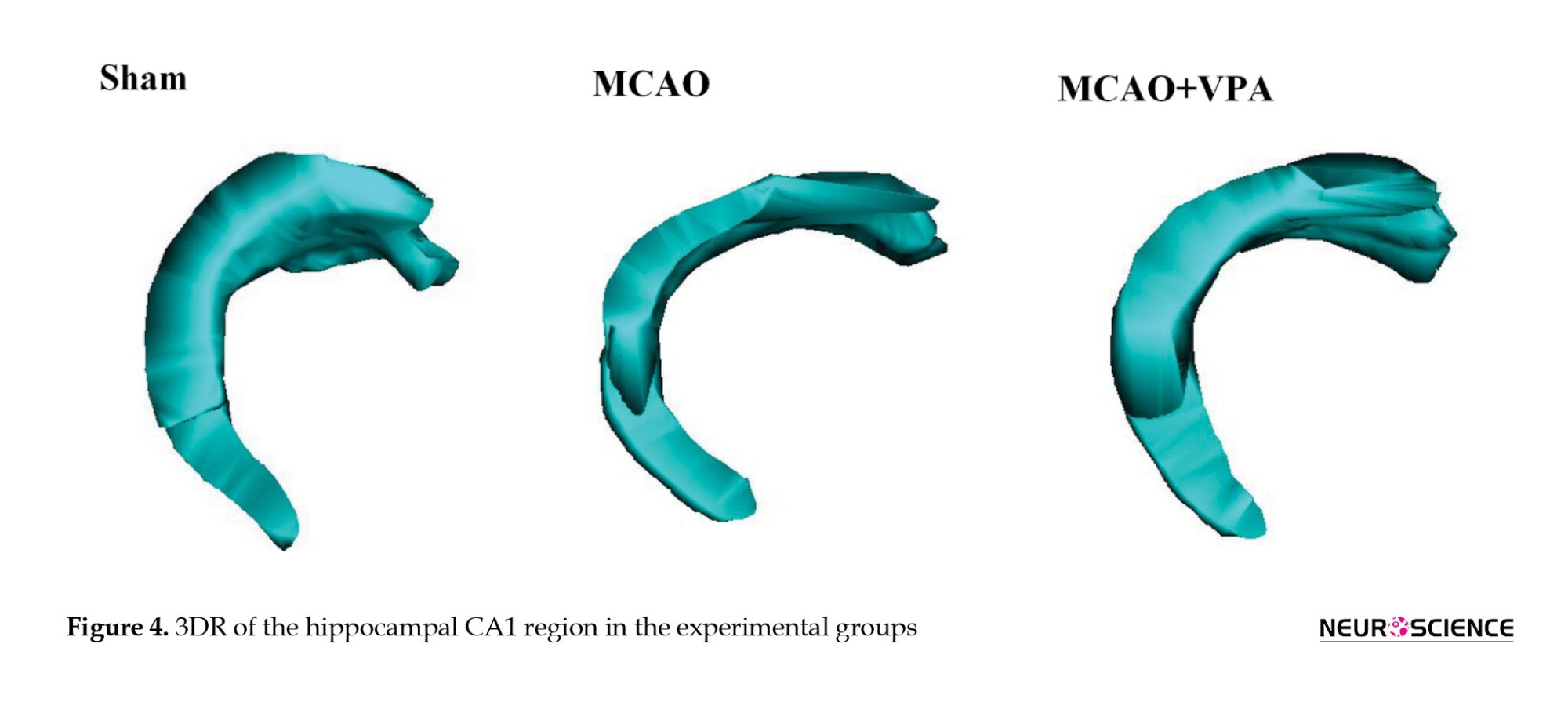

Voronoi tessellations

In our study, a Voronoi tessellation was utilized to assess the spatial organization of pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region of the ischemic hemisphere across all experimental groups. Voronoi tessellation was performed on microscopic images of randomly sampled fields in the CA1 of the ischemic hemisphere of rats. CA1 pyramidal neurons were mapped by the ImageJ Voronoi Plugin, which involved outlining a polygon around each point representing a CA1 neuron (Moroni et al., 2008). The Voronoi polygons varied in size, and the variation in polygon areas was evaluated through their variance. The coefficient of variation (CV), calculated as the standard deviation of the polygon areas divided by the mean and multiplied by 100, indicated the spatial distribution of pyramidal neurons. CV values between 33% and 64% indicated a random distribution; values below 33% suggested a regular distribution; and values exceeding 64% indicated a clustered distribution (Duyckaerts & Godefroy, 2000).

Assessment of the total number of CA1 pyramidal dead neurons

A population of pyknotic, shrunken, and smaller cells was observed among pyramidal neurons in MCAO animals, which were considered dead neurons. The total number of dead neurons in the CA1 region of the ischemic hemisphere was assessed by a computer connected to a Nikon E200 light microscope equipped with an oil-immersion lens at 40x magnification. Following the optical disector technique, an unbiased counting frame was superimposed onto monitor images of the sections. Microscopic fields were systematically sampled by moving the microscope stage in x and y with equal increments. Dead neurons within the sampling frame (area of counting frames “a/f” multiplied by disector height “h”) were counted. The total number of dead neurons in the CA1 region was determined by multiplying the numerical density (Nv) and the CA1volume, estimated by the Cavalieri method (Equation 1) (Jahromi et al., 2024).

1. Nv=[ΣQ/ΣP×(a / f)×h] × [t/BA]

“ΣQ” denotes the total number of dead neurons in the CA1 region of the ischemic hemisphere; “ΣP” was the total number of counting frames; “t” was the mean section thickness obtained using the microcator; and “BA” the block advance, set at 50 µm (Asadinejad et al., 2024).

Three-dimensional reconstruction (3DR)

To assess 3D visualization of the CA1 region, serial sections of the ischemic hemisphere were used in all experimental groups. To determine the 3D features of the CA1 region, a 3DR was generated by the “reconstruct”. The program creates 3DR figures by reconstructing montages, visualizing, and aligning serial sections (Helander, 2006).

Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay

The hippocampus from the ischemic hemispheres was dissected, and the MDA levels were measured by the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay. Each issue sample was homogenized and then centrifuged (12,000 rpm) for 15 minutes. The resulting standards and supernatants (1,1,3,3-tetra ethoxy propane, Sigma, Germany) were combined via a mixture of 0.25 N hydrochloric acid (Sigma, Germany), 20% trichloroacetic acid (Sigma, Germany), and 0.8% thiobarbituric acid (Sigma, Germany).

The solution was then incubated at 90 ˚C for one h and subsequently centrifuged (12,000 rpm) for 5 minutes. Finally, the absorbance of the samples was measured by a microplate reader (Biotek, USA) at 532 nm (Naseh et al., 2020).

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism software, version 6, and presented as Mean±SEM in the experimental groups. Statistical analysis was done on normally distributed data using analysis of variance (ANOVA) (post hoc Tukey’s test), and on non-parametric data by Kruskal-Wallis (post hoc Mann-Whitney U test). Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation analysis was utilized to explore the possible associations between the stereological and biochemical parameters. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Stereological assays

Spatial arrangement of CA1 pyramidal neurons

Figure 2 shows the parameters of Voronoi polygon areas for CA1 pyramidal neurons. The Voronoi polygon area’s distribution in the range of 1-202 μm2 was 93% in the sham group, 32% in the MCAO group, and only 83% in the MCAO + VPA group. The distribution polygon in the MCAO group was shifted to the right, whereas VPA treatment shifted it to the left, closer to the sham group (Figure 2B).

The mean Voronoi polygon area increased significantly in the MCAO group compared to the sham group (P<0.001). Although, VPA significantly decreased this parameter (P<0.001) (Figures 2A and 2C).

The CV of polygon areas was 29.2%, 47.8%, and 27.5% in the sham, MCAO, and MCAO + VPA groups, respectively. These parameters demonstrate that the neuronal distribution in the sham and MCAO + VPA groups was regular, while the MCAO group showed a random distribution (Figure 2D).

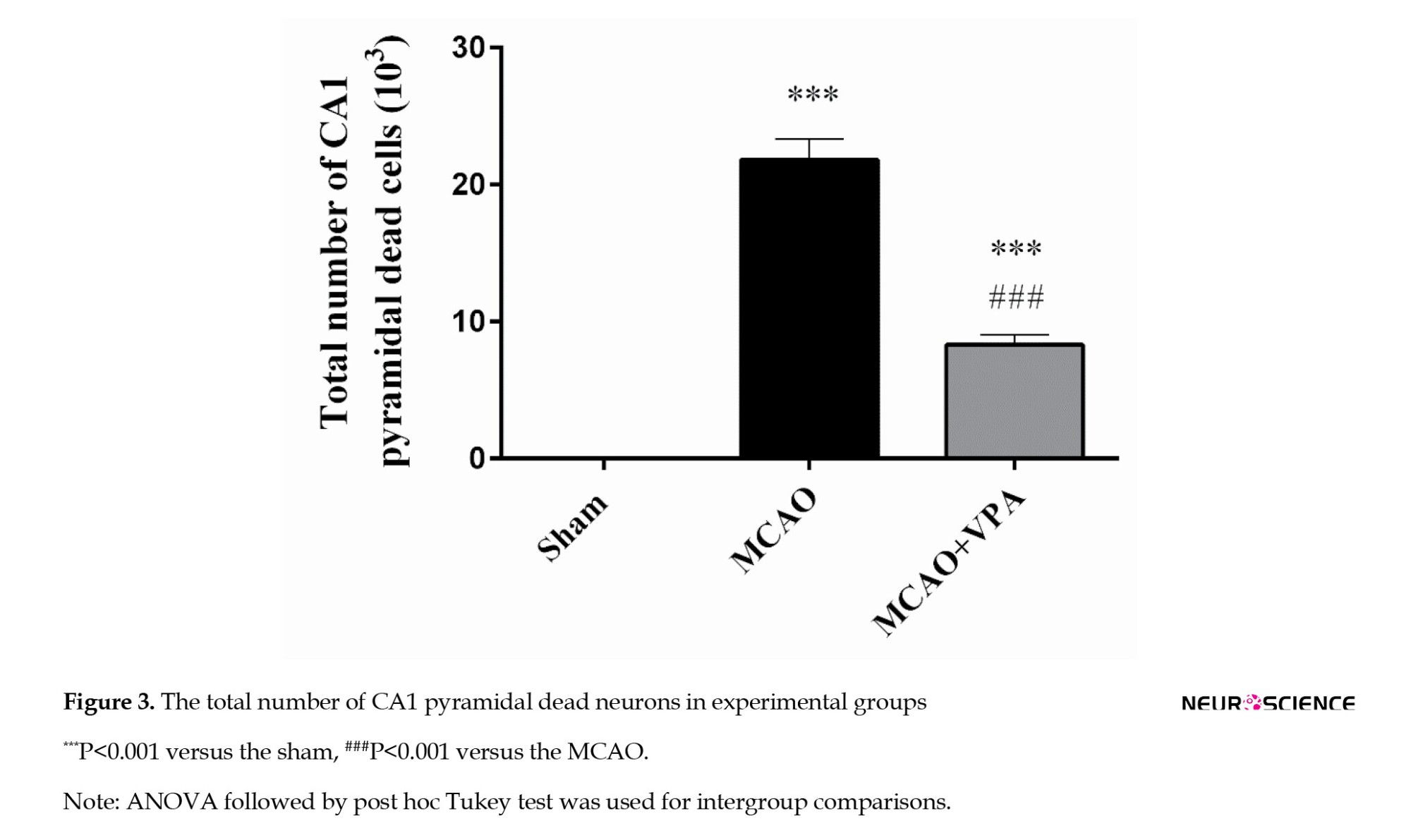

The total number of CA1 pyramidal dead neurons

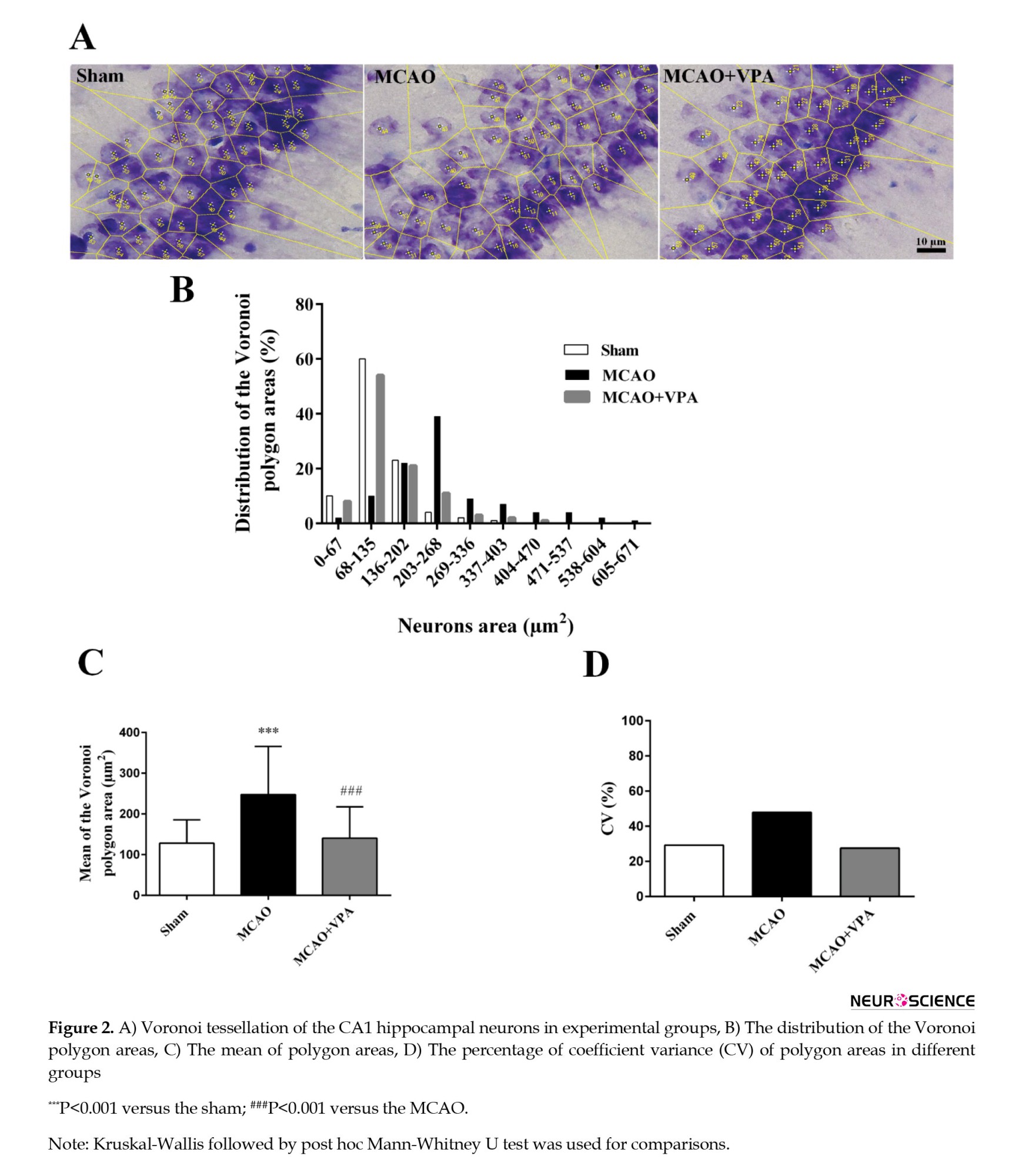

The total number of dead pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region was significantly higher in the MCAO group (21.82±1.52×103) than in the sham group (0) (P<0.001). However, treatment with VPA resulted in a significant reduction of this parameter relative to the MCAO group (21.82±1.52 vs 8.32±0.72; P<0.001) (Figure 3).

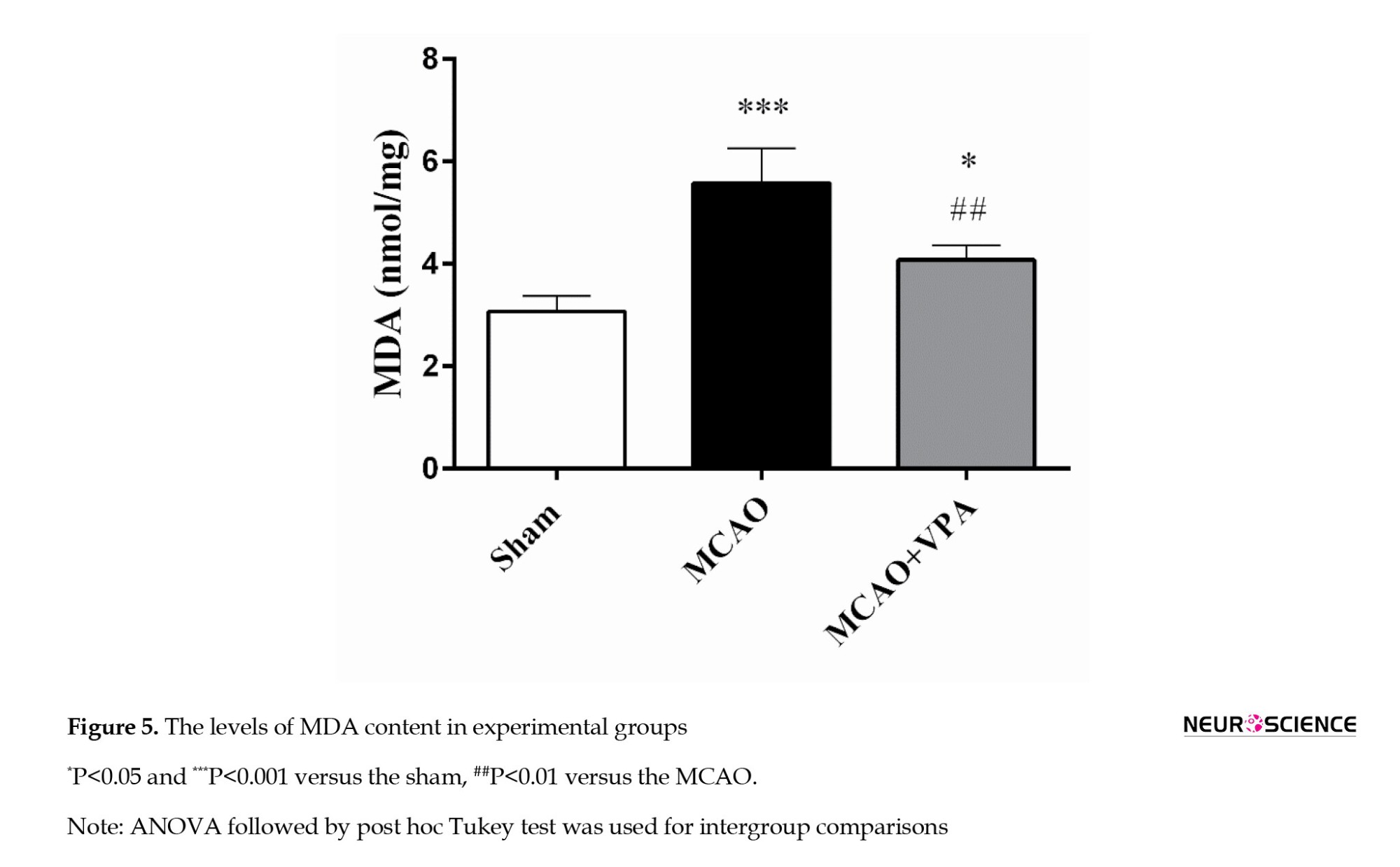

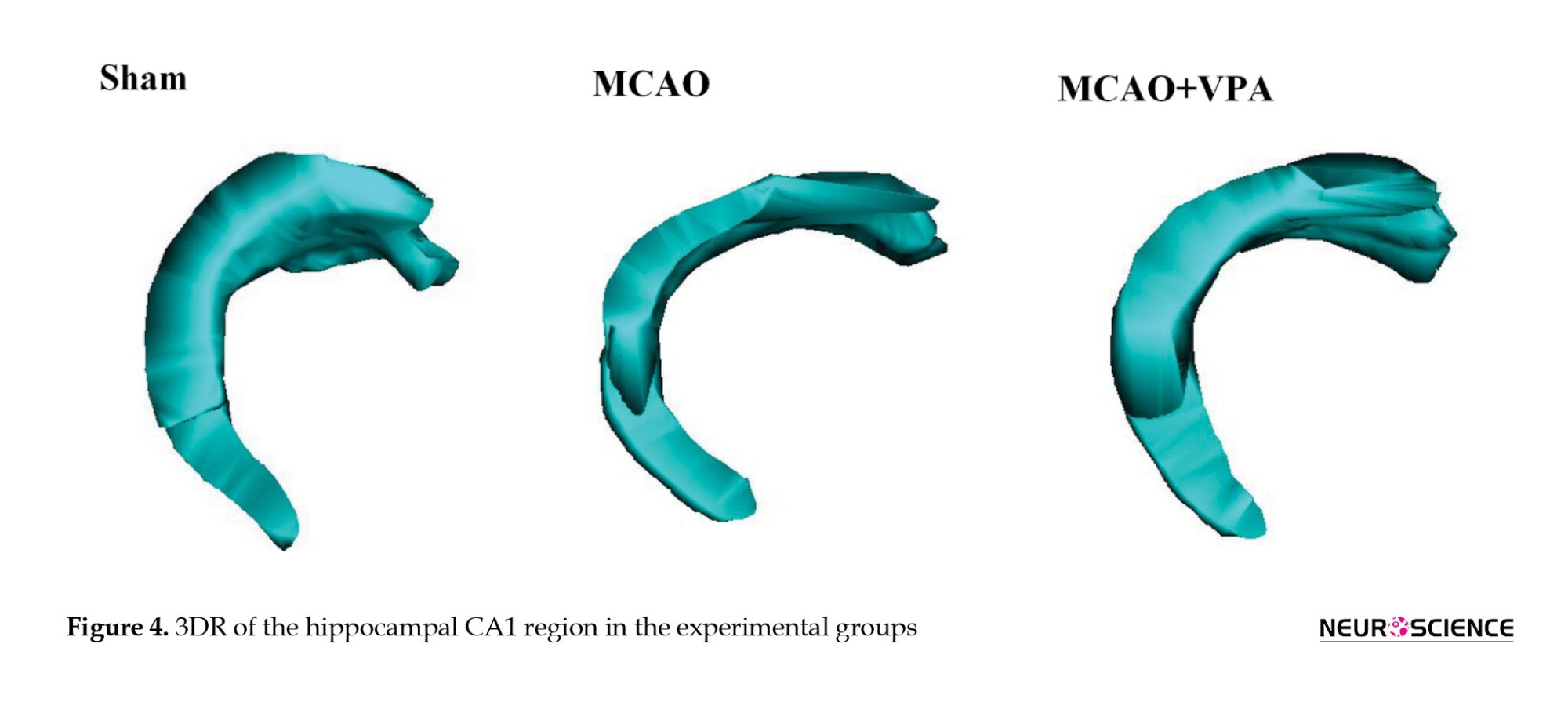

3DR

Figure 4 shows the 3DR of the CA1 hippocampal region. The structure of CA1 in the MCAO group showed significant deformation compared to the sham group. However, the shape of CA1 in the MCAO + VPA group remained within the normal range and was close to that of sham group.

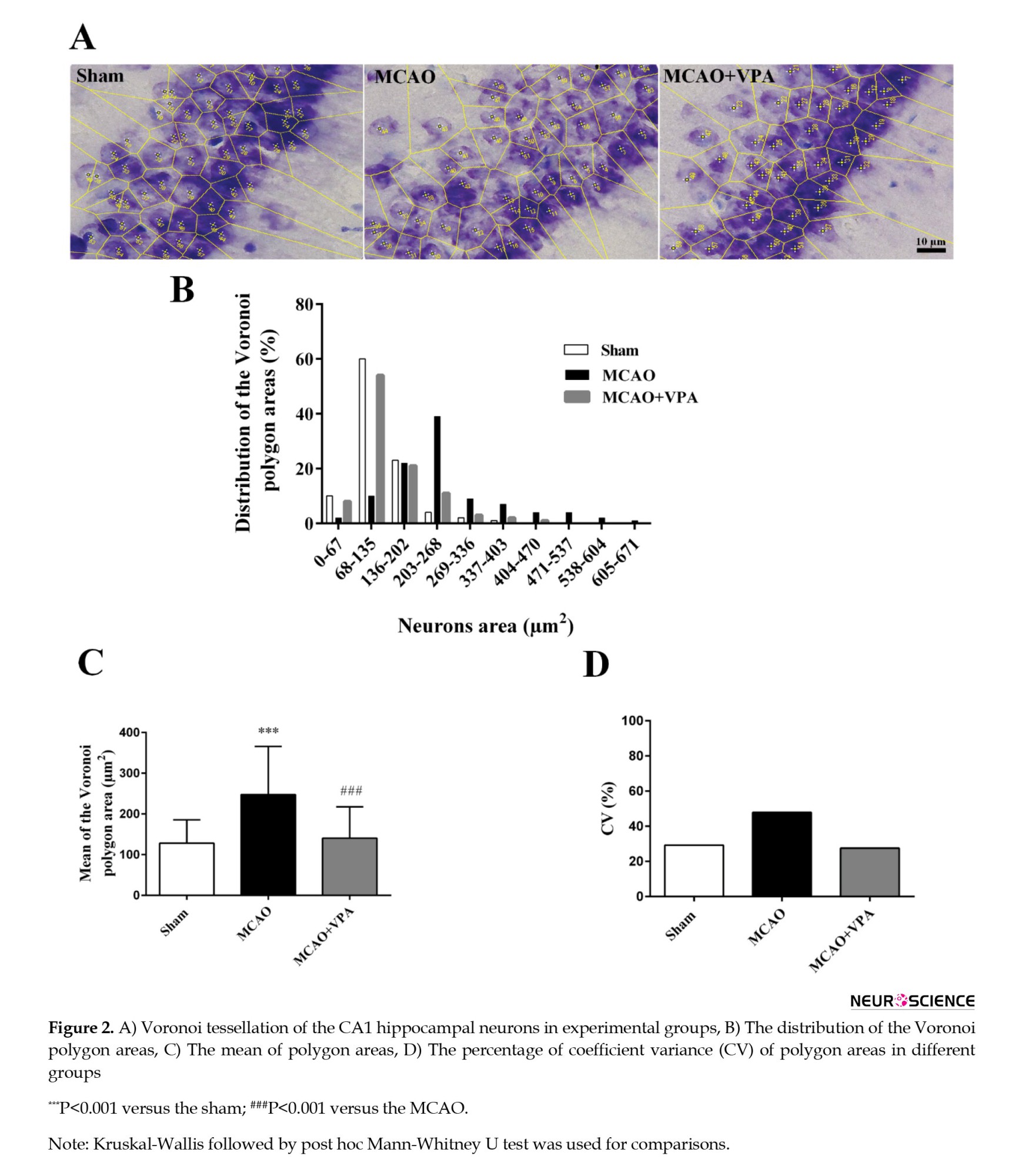

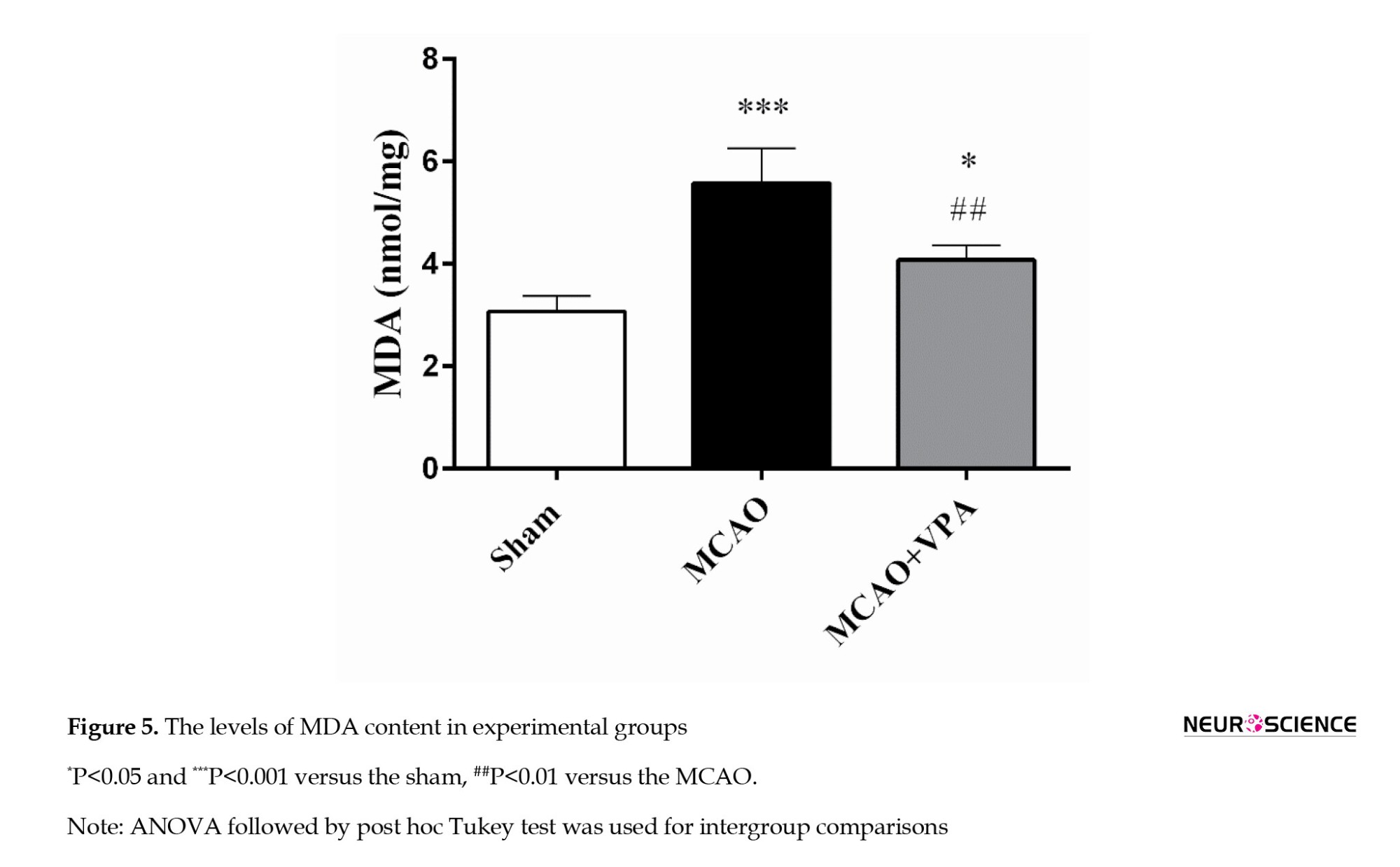

Biochemical study

The MDA levels

The MDA levels were significantly elevated in the MCAO and MCAO + VPA groups compared to those in the sham group (P<0.001 and P<0.05, respectively). Notably, VPA treatment significantly reduced this parameter in the MCAO + VPA group compared to the MCAO group (P<0.01) (Figure 5).

Correlation analysis

The possible associations between the stereological and biochemical parameters were investigated using Pearson’s correlation analysis.

The mean Voronoi polygon area indicated a strong positive correlation with the number of CA1 dead neurons, in the MCAO group (r=0.9577, P=0.0026) and in the MCAO + VPA group (r=0.9927, P=0.001). Also, the mean of the Voronoi polygon area was associated with the MDA levels in the MCAO (r=0.9087, P=0.0326) and MCAO + VPA (r=0.9392, P=0.0178) groups. Furthermore, a direct correlation was observed between the number of CA1 dead neurons and MDA levels in both the MCAO (r=0.8964, P=0.0394) and MCAO+VPA (r=0.9382, P=0.0183) rats.

Discussion

The present study examined the spatial arrangement of CA1 pyramidal neurons, the three-dimensional structure of the hippocampus, and the biochemical changes in MCAO rats. Our findings demonstrated that MCAO led to an increase in the spatial arrangement, total number of CA1 dead neurons, and oxidative stress levels. Also, we found a positive relationship between these parameters in the hippocampus.

Hippocampal neurons are vulnerable to oxidative stress owing to their high oxygen consumption, the significant presence of unsaturated fatty acids, and comparatively low antioxidant concentration (Huang et al., 2015). In our study, increased oxidative stress (MDA content) induced CA1 neuronal death (i.e. an increase in the total number of pyramidal dead neurons) and caused structural changes (i.e. an increase in Voronoi polygon area and three-dimensional deformation) within the hippocampal CA1 region of MCAO rats. Similarly, it has been shown that hippocampal oxidative stress reduces neurogenesis and increases neuronal death (Abbah et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2012). These changes occur through a cascade of damaging processes affecting cell membranes, proteins, and DNA, leading to reduced cell viability, neuroinflammation, and cognitive impairment. In addition, increased ROS production in the hippocampus after cerebral ischemia is associated with mitochondrial oxidative stress, suggesting that oxidative damage and cell death may be of mitochondrial origin (Friberg et al., 2002). This series of events highlights the crucial role of maintaining redox balance in preventing neurodegeneration, and structural and functional changes.

Our findings implied that the VPA could restore the hippocampal spatial arrangement, reverse three-dimensional deformation, and decrease the total number of dead neurons and MDA levels induced by MCAO. Our results indicated that reduced cell death in the CA1 region, along with improvements in hippocampal cell spatial arrangement and three-dimensional structure, may be correlated with reduced oxidative stress. Our findings indicated that lowering oxidative stress reduces neuronal death in this area and improves the spatial arrangement and three-dimensional structure of hippocampal cells. This proposes that VPA protects on hippocampal CA1 cells and maintains their organization by reducing oxidative stress. Recently, we showed that VPA prevented volume shrinkage and neuronal depletion in the hippocampal CA1 and dentate gyrus subregions after MCAO, confirming the improvement of MCAO-induced structural changes in the present study (Naseh et al., 2022). Consistent with our findings, it has been reported that VPA can prevent CA1 neurons from dying on the seventh day following transient brain ischemia and improve memory function (Xuan et al., 2012).

The neuroprotective effects of VPA after cerebral ischemia could involve several mechanisms, such as substantial inhibition of ischemia-induced cerebral oxidation and inflammation, reduced HDAC activity, and the superinduction of the 70-kilodalton heat shock protein (Xuan et al., 2012). Some evidence has demonstrated that VPA may exert neuroprotective effects by attenuating inflammatory pathways that lead to neuronal cell death (Xuan et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2019). VPA treatment significantly reduced inflammation-related pathways leading to neuronal loss, specifically in the hippocampal CA1 region. Furthermore, VPA enhanced survival and viability of hippocampal neurons in vitro in a brain ischemia model (oxygen-glucose deprivation) (Zhu et al., 2019). Similarly, VPA effectively prevented reduction in neuronal cell viability following glutamate‑induced excitotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells by reducing oxidative parameters, including H2O2 and MDA (Terzioğlu Bebitoğlu et al., 2020).

VPA may offer neuroprotective effects and promote structural recovery following cerebral ischemia by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, among other mechanisms. Previous studies have indicated that HDAC inhibitors, such as VPA, may enhance the differentiation and survival of neuronal progenitors in the hippocampus through activation of phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (p-CREB), which in turn regulates the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Kim et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012). VPA has been shown to reduce infarct volume, promote angiogenesis, and support functional restoration following MCAO in rats. These processes are mediated by pathways that inhibit histone deacetylases and upregulate hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α, which, in turn, increases the activity of matrix metalloproteinases 2/9 and vascular endothelial growth factor (Wang et al., 2012). Furthermore, another study suggested that VPA may protect against brain injury following transient focal cerebral ischemia by reducing BBB disruption and brain edema. These protective effects appear to involve the suppression of MCAO-induced overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-9, and downregulation of zonula occludens-1 and Claudin-5 (Wang et al., 2011). Notably, although various mechanisms have been proposed to explain VPA’s neuroprotective effects in experimental brain ischemia, further research is still needed.

In summary, our study found that VPA could restore the spatial arrangement and three-dimensional structure of the hippocampal CA1 region by reducing the number of dead cells. Additionally, the observed decrease in oxidative stress plays a crucial role in preventing structural changes following MCAO.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (Code: IR.SUMS.REC.1399.1343).

Funding

The present work was financially supported Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (Grant No.: 1399.1343).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Masoud Haghani, Mohammad Reza Namavar, Zahra Naseh, Samira Panahi Kokhd, and Maryam Naseh; Methodology: Masoud Haghani, Mohammad Reza Namavar, Zahra Naseh and Samira Panahi Kokhdan; Data collection: Zahra Naseh and Samira Panahi Kokhdan; Data curation: Masoud Haghani, Mohammad Reza Namavar, Farzaneh Dehghani and Jafar Vatanparast; Investigation: Masoud Haghani and Mohammad Reza Namavar, Zahra Naseh and Samira Panahi Kokhdan; Validation and visualization: Farzaneh Dehghani, Jafar Vatanparast, and Maryam Naseh; Formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, software, supervision, and writing the original draft: Maryam Naseh; Review and editing: Farzaneh Dehghani, Jafar Vatanparast, and Maryam Naseh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Histomorphometry and Stereology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

References

Brain ischemia is one of the most prevalent cerebrovascular diseases and is the second contributor to global morbidity and mortality. Cerebral ischemia can occur when blood flow to a part of the brain is temporarily restricted because of embolism, thrombosis, or systemic hypoperfusion, and then blood flow is restored to the affected areas, which is called reperfusion. The pathological mechanisms of ischemia-reperfusion injury include oxidative stress, inflammation, excitotoxicity, and the complement system, which lead to necrosis and apoptosis in the ischemic area (Jiang et al., 2022). These destructive events can ultimately cause neurological deficits and behavioral dysfunctions (Deb et al., 2010). After reperfusion, oxygen and glucose re-enter the brain, further challenging the ischemic tissue. Oxidative glycolysis of glucose yields substantial amounts of the reduced cofactors nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2), and during electron transfer, superoxide anion (O2−) is generated, contributing to the buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (Nishi et al., 2005). The excessive generation of oxidative free radicals promotes lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, nitrification, and DNA and mitochondrial damage (Beckman, 1996). Additionally, ROS and RNS cause leukocyte recruitment, chemokine and inflammatory mediator production, impairment of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), and the consequent cerebral edema (del Zoppo & Mabuchi, 2003). Currently, mechanical thrombectomy and intravenous thrombolysis are the primary therapies for ischemic stroke; nevertheless, each method has its own set of restrictions. Therefore, to overcome these problems, researchers need to identify new neuroprotective agents for the treatment of ischemic stroke.

Sodium valproate (VPA) is widely utilized to treat neurological diseases, including bipolar disorder and seizures, and can also be used as a new strategy for treating ischemic stroke (Johannessen, 2000). It has been shown that VPA can have protective effects against animal models of ischemic stroke by increasing antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities reducing the production of oxidative metabolites, as well as its capacity to restrain histolysis (HDAC) and suppress glycogen synthase kinase 3 (Chen et al., 2014; Pang et al., 2016; Shao et al., 2005; Silva et al., 2018). Similarly, the antioxidant activity of VPA has been investigated in vitro, and it has been suggested that the mechanism of VPA can be through the inhibition of glutamate-induced neurotoxicity, disturbances in intracellular calcium homeostasis, DNA fragmentation, protein oxidation, and lipid peroxidation (Kanai et al., 2004; Rekling, 2003).

In a previous study, we examined the effects of VPA on synaptic plasticity and memory function impairments in a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model (Naseh et al., 2022). Building on the previous study, this research investigated the spatial organization of pyramidal neurons, the three-dimensional structure of the hippocampal CA1 region, and oxidative stress changes in MCAO rats. Studying possible microanatomical changes in the hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons after MCAO is an excellent opportunity to better explain brain dysfunction after stroke. Furthermore, in studies related to cerebral ischemia, most researchers have focused on neuronal quantity (Moralí et al., 2005), with comparatively little attention paid to the spatial organization of neurons or to the three-dimensional structure of CA1 region, which may critically influence functional recovery. Therefore, we decided to assess the impact of VPA on the spatial arrangement and three-dimensional structure of the CA1 pyramidal neurons in an experimental MCAO model.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Thirty male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–250 g, 6–8 weeks old) were obtained from the Center of Comparative and Experimental Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Animals were housed under controlled conditions (21±2 °C; 12 h light/ 12 h dark cycle) with free access to food and water. The experimental procedure was approved by the Committee for the Ethics of Scientific Research of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, and all procedures complied with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Experimental groups

The rats were randomly assigned to three groups: Sham, MCAO, and MCAO + VPA (n=10 in each group).

The MCAO model was established as described in our previous studies (Naseh et al., 2022; Naseh et al., 2020). Briefly, the rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal (IP) injection of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Then, the right common carotid and external carotid arteries (ECA) were exposed. A silicone-coated monofilament suture (4043PK5Re, Doccol, USA) was introduced to the external carotid artery (ECA) and advanced through the internal carotid artery (ICA) to occlude the middle cerebral artery (MCA) for an hour. The suture was subsequently removed, allowing reperfusion. Notably, the body temperature of rats was controlled by a rectal thermometer. Sham surgery was performed similar to the MCAO protocol except without inserting a monofilament into the ICA. VPA (300 mg/kg (Mann Brukner et al., 2018; Naseh et al., 2022; Xuan et al., 2012); Merck, Germany) was solubilized in 300 μL distilled water, and injected IP on days 0, 1, 2, and 3 post-MCAO (Figure 1). Intraperitoneal administration was chosen to ensure accurate dosing and to avoid the stress associated with oral gavage.

One week after MCAO, the brains (ischemic hemisphere) of five animals were removed and preserved in 10% buffered formaldehyde for a week. The brains were then placed in 30% sucrose solution for three days and stored at -80 °C until further analysis (stereological study). Additionally, the brains (ischemic hemisphere) of five other rats were removed and kept at -80 °C until biochemical evaluations.

Stereological assessment

The ischemic hemisphere of the brain was coronally and serially sectioned at 50 μm thickness using a cryostat (Microm HM 525, Germany) and stained with cresyl violet. The CA1 hippocampal region was identified according to the Paxinos and Watson Atlas (Paxinos & Watson, 2007).

Voronoi tessellations

In our study, a Voronoi tessellation was utilized to assess the spatial organization of pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region of the ischemic hemisphere across all experimental groups. Voronoi tessellation was performed on microscopic images of randomly sampled fields in the CA1 of the ischemic hemisphere of rats. CA1 pyramidal neurons were mapped by the ImageJ Voronoi Plugin, which involved outlining a polygon around each point representing a CA1 neuron (Moroni et al., 2008). The Voronoi polygons varied in size, and the variation in polygon areas was evaluated through their variance. The coefficient of variation (CV), calculated as the standard deviation of the polygon areas divided by the mean and multiplied by 100, indicated the spatial distribution of pyramidal neurons. CV values between 33% and 64% indicated a random distribution; values below 33% suggested a regular distribution; and values exceeding 64% indicated a clustered distribution (Duyckaerts & Godefroy, 2000).

Assessment of the total number of CA1 pyramidal dead neurons

A population of pyknotic, shrunken, and smaller cells was observed among pyramidal neurons in MCAO animals, which were considered dead neurons. The total number of dead neurons in the CA1 region of the ischemic hemisphere was assessed by a computer connected to a Nikon E200 light microscope equipped with an oil-immersion lens at 40x magnification. Following the optical disector technique, an unbiased counting frame was superimposed onto monitor images of the sections. Microscopic fields were systematically sampled by moving the microscope stage in x and y with equal increments. Dead neurons within the sampling frame (area of counting frames “a/f” multiplied by disector height “h”) were counted. The total number of dead neurons in the CA1 region was determined by multiplying the numerical density (Nv) and the CA1volume, estimated by the Cavalieri method (Equation 1) (Jahromi et al., 2024).

1. Nv=[ΣQ/ΣP×(a / f)×h] × [t/BA]

“ΣQ” denotes the total number of dead neurons in the CA1 region of the ischemic hemisphere; “ΣP” was the total number of counting frames; “t” was the mean section thickness obtained using the microcator; and “BA” the block advance, set at 50 µm (Asadinejad et al., 2024).

Three-dimensional reconstruction (3DR)

To assess 3D visualization of the CA1 region, serial sections of the ischemic hemisphere were used in all experimental groups. To determine the 3D features of the CA1 region, a 3DR was generated by the “reconstruct”. The program creates 3DR figures by reconstructing montages, visualizing, and aligning serial sections (Helander, 2006).

Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay

The hippocampus from the ischemic hemispheres was dissected, and the MDA levels were measured by the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay. Each issue sample was homogenized and then centrifuged (12,000 rpm) for 15 minutes. The resulting standards and supernatants (1,1,3,3-tetra ethoxy propane, Sigma, Germany) were combined via a mixture of 0.25 N hydrochloric acid (Sigma, Germany), 20% trichloroacetic acid (Sigma, Germany), and 0.8% thiobarbituric acid (Sigma, Germany).

The solution was then incubated at 90 ˚C for one h and subsequently centrifuged (12,000 rpm) for 5 minutes. Finally, the absorbance of the samples was measured by a microplate reader (Biotek, USA) at 532 nm (Naseh et al., 2020).

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism software, version 6, and presented as Mean±SEM in the experimental groups. Statistical analysis was done on normally distributed data using analysis of variance (ANOVA) (post hoc Tukey’s test), and on non-parametric data by Kruskal-Wallis (post hoc Mann-Whitney U test). Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation analysis was utilized to explore the possible associations between the stereological and biochemical parameters. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Stereological assays

Spatial arrangement of CA1 pyramidal neurons

Figure 2 shows the parameters of Voronoi polygon areas for CA1 pyramidal neurons. The Voronoi polygon area’s distribution in the range of 1-202 μm2 was 93% in the sham group, 32% in the MCAO group, and only 83% in the MCAO + VPA group. The distribution polygon in the MCAO group was shifted to the right, whereas VPA treatment shifted it to the left, closer to the sham group (Figure 2B).

The mean Voronoi polygon area increased significantly in the MCAO group compared to the sham group (P<0.001). Although, VPA significantly decreased this parameter (P<0.001) (Figures 2A and 2C).

The CV of polygon areas was 29.2%, 47.8%, and 27.5% in the sham, MCAO, and MCAO + VPA groups, respectively. These parameters demonstrate that the neuronal distribution in the sham and MCAO + VPA groups was regular, while the MCAO group showed a random distribution (Figure 2D).

The total number of CA1 pyramidal dead neurons

The total number of dead pyramidal neurons in the CA1 region was significantly higher in the MCAO group (21.82±1.52×103) than in the sham group (0) (P<0.001). However, treatment with VPA resulted in a significant reduction of this parameter relative to the MCAO group (21.82±1.52 vs 8.32±0.72; P<0.001) (Figure 3).

3DR

Figure 4 shows the 3DR of the CA1 hippocampal region. The structure of CA1 in the MCAO group showed significant deformation compared to the sham group. However, the shape of CA1 in the MCAO + VPA group remained within the normal range and was close to that of sham group.

Biochemical study

The MDA levels

The MDA levels were significantly elevated in the MCAO and MCAO + VPA groups compared to those in the sham group (P<0.001 and P<0.05, respectively). Notably, VPA treatment significantly reduced this parameter in the MCAO + VPA group compared to the MCAO group (P<0.01) (Figure 5).

Correlation analysis

The possible associations between the stereological and biochemical parameters were investigated using Pearson’s correlation analysis.

The mean Voronoi polygon area indicated a strong positive correlation with the number of CA1 dead neurons, in the MCAO group (r=0.9577, P=0.0026) and in the MCAO + VPA group (r=0.9927, P=0.001). Also, the mean of the Voronoi polygon area was associated with the MDA levels in the MCAO (r=0.9087, P=0.0326) and MCAO + VPA (r=0.9392, P=0.0178) groups. Furthermore, a direct correlation was observed between the number of CA1 dead neurons and MDA levels in both the MCAO (r=0.8964, P=0.0394) and MCAO+VPA (r=0.9382, P=0.0183) rats.

Discussion

The present study examined the spatial arrangement of CA1 pyramidal neurons, the three-dimensional structure of the hippocampus, and the biochemical changes in MCAO rats. Our findings demonstrated that MCAO led to an increase in the spatial arrangement, total number of CA1 dead neurons, and oxidative stress levels. Also, we found a positive relationship between these parameters in the hippocampus.

Hippocampal neurons are vulnerable to oxidative stress owing to their high oxygen consumption, the significant presence of unsaturated fatty acids, and comparatively low antioxidant concentration (Huang et al., 2015). In our study, increased oxidative stress (MDA content) induced CA1 neuronal death (i.e. an increase in the total number of pyramidal dead neurons) and caused structural changes (i.e. an increase in Voronoi polygon area and three-dimensional deformation) within the hippocampal CA1 region of MCAO rats. Similarly, it has been shown that hippocampal oxidative stress reduces neurogenesis and increases neuronal death (Abbah et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2012). These changes occur through a cascade of damaging processes affecting cell membranes, proteins, and DNA, leading to reduced cell viability, neuroinflammation, and cognitive impairment. In addition, increased ROS production in the hippocampus after cerebral ischemia is associated with mitochondrial oxidative stress, suggesting that oxidative damage and cell death may be of mitochondrial origin (Friberg et al., 2002). This series of events highlights the crucial role of maintaining redox balance in preventing neurodegeneration, and structural and functional changes.

Our findings implied that the VPA could restore the hippocampal spatial arrangement, reverse three-dimensional deformation, and decrease the total number of dead neurons and MDA levels induced by MCAO. Our results indicated that reduced cell death in the CA1 region, along with improvements in hippocampal cell spatial arrangement and three-dimensional structure, may be correlated with reduced oxidative stress. Our findings indicated that lowering oxidative stress reduces neuronal death in this area and improves the spatial arrangement and three-dimensional structure of hippocampal cells. This proposes that VPA protects on hippocampal CA1 cells and maintains their organization by reducing oxidative stress. Recently, we showed that VPA prevented volume shrinkage and neuronal depletion in the hippocampal CA1 and dentate gyrus subregions after MCAO, confirming the improvement of MCAO-induced structural changes in the present study (Naseh et al., 2022). Consistent with our findings, it has been reported that VPA can prevent CA1 neurons from dying on the seventh day following transient brain ischemia and improve memory function (Xuan et al., 2012).

The neuroprotective effects of VPA after cerebral ischemia could involve several mechanisms, such as substantial inhibition of ischemia-induced cerebral oxidation and inflammation, reduced HDAC activity, and the superinduction of the 70-kilodalton heat shock protein (Xuan et al., 2012). Some evidence has demonstrated that VPA may exert neuroprotective effects by attenuating inflammatory pathways that lead to neuronal cell death (Xuan et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2019). VPA treatment significantly reduced inflammation-related pathways leading to neuronal loss, specifically in the hippocampal CA1 region. Furthermore, VPA enhanced survival and viability of hippocampal neurons in vitro in a brain ischemia model (oxygen-glucose deprivation) (Zhu et al., 2019). Similarly, VPA effectively prevented reduction in neuronal cell viability following glutamate‑induced excitotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells by reducing oxidative parameters, including H2O2 and MDA (Terzioğlu Bebitoğlu et al., 2020).

VPA may offer neuroprotective effects and promote structural recovery following cerebral ischemia by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, among other mechanisms. Previous studies have indicated that HDAC inhibitors, such as VPA, may enhance the differentiation and survival of neuronal progenitors in the hippocampus through activation of phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (p-CREB), which in turn regulates the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (Kim et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012). VPA has been shown to reduce infarct volume, promote angiogenesis, and support functional restoration following MCAO in rats. These processes are mediated by pathways that inhibit histone deacetylases and upregulate hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1α, which, in turn, increases the activity of matrix metalloproteinases 2/9 and vascular endothelial growth factor (Wang et al., 2012). Furthermore, another study suggested that VPA may protect against brain injury following transient focal cerebral ischemia by reducing BBB disruption and brain edema. These protective effects appear to involve the suppression of MCAO-induced overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-9, and downregulation of zonula occludens-1 and Claudin-5 (Wang et al., 2011). Notably, although various mechanisms have been proposed to explain VPA’s neuroprotective effects in experimental brain ischemia, further research is still needed.

In summary, our study found that VPA could restore the spatial arrangement and three-dimensional structure of the hippocampal CA1 region by reducing the number of dead cells. Additionally, the observed decrease in oxidative stress plays a crucial role in preventing structural changes following MCAO.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (Code: IR.SUMS.REC.1399.1343).

Funding

The present work was financially supported Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (Grant No.: 1399.1343).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Masoud Haghani, Mohammad Reza Namavar, Zahra Naseh, Samira Panahi Kokhd, and Maryam Naseh; Methodology: Masoud Haghani, Mohammad Reza Namavar, Zahra Naseh and Samira Panahi Kokhdan; Data collection: Zahra Naseh and Samira Panahi Kokhdan; Data curation: Masoud Haghani, Mohammad Reza Namavar, Farzaneh Dehghani and Jafar Vatanparast; Investigation: Masoud Haghani and Mohammad Reza Namavar, Zahra Naseh and Samira Panahi Kokhdan; Validation and visualization: Farzaneh Dehghani, Jafar Vatanparast, and Maryam Naseh; Formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, software, supervision, and writing the original draft: Maryam Naseh; Review and editing: Farzaneh Dehghani, Jafar Vatanparast, and Maryam Naseh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Histomorphometry and Stereology Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran.

References

Abbah, J., Vacher, C. M., Goldstein, E. Z., Li, Z., Kundu, S., & Talbot, B., et al. (2022). Oxidative stress-induced damage to the developing hippocampus is mediated by GSK3β. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 42(24), 4812–4827. [DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2389-21.2022] [PMID]

Asadi Nejad, H., Yousefi Nejad, A., Akbari, S., Naseh, M., Shid Moosavi, S. M., & Haghani, M. (2024). The low and high doses administration of lutein improves memory and synaptic plasticity impairment through different mechanisms in a rat model of vascular dementia. Plos One, 19(5), e0302850.[DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0302850] [PMID]

Beckman, J. S. (1996). Oxidative damage and tyrosine nitration from peroxynitrite. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 9(5), 836-844. [DOI:10.1021/tx9501445] [PMID]

Chen, S., Wu, H., Klebe, D., Hong, Y., & Zhang, J. (2014). Valproic acid: A new candidate of therapeutic application for the acute central nervous system injuries. Neurochemical Research, 39(9), 1621-1633. [DOI:10.1007/s11064-014-1241-2] [PMID]

Deb, P., Sharma, S., & Hassan, K. M. (2010). Pathophysiologic mechanisms of acute ischemic stroke: An overview with emphasis on therapeutic significance beyond thrombolysis. Pathophysiology: The Official Journal of the International Society for Pathophysiology, 17(3), 197–218. [DOI:10.1016/j.pathophys.2009.12.001] [PMID]

del Zoppo, G. J., & Mabuchi, T. (2003). Cerebral microvessel responses to focal ischemia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 23(8), 879-894. [DOI:10.1097/01.WCB.0000078322.96027.78] [PMID]

Duyckaerts, C., & Godefroy, G. (2000). Voronoi tessellation to study the numerical density and the spatial distribution of neurones. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy, 20(1), 83-92. [DOI:10.1016/S0891-0618(00)00064-8] [PMID]

Friberg, H., Wieloch, T., & Castilho, R. F. (2002). Mitochondrial oxidative stress after global brain ischemia in rats. Neuroscience Letters, 334(2), 111-114. [DOI:10.1016/S0304-3940(02)01116-3] [PMID]

Helander, H. F. (2006). Re: Reconstruct: A free editor for serial section microscopy. Journal of Microscopy, 224(Pt 2), 211-212. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01691.x] [PMID]

Huang, T. T., Leu, D., & Zou, Y. (2015). Oxidative stress and redox regulation on hippocampal-dependent cognitive functions. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 576, 2–7.[DOI:10.1016/j.abb.2015.03.014] [PMID]

Huang, T. T., Zou, Y., & Corniola, R. (2012). Oxidative stress and adult neurogenesis--effects of radiation and superoxide dismutase deficiency. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 23(7), 738–744. [DOI:10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.04.003] [PMID]

Jahromi, H. M., Rafati, A., Karbalay-Doust, S., Keshavarz, S., & Naseh, M. (2024). The combination treatment of hypothermia and intranasal insulin ameliorates the structural and functional changes in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Brain Structure and Function, 229(4), 947-957. [DOI:10.1007/s00429-024-02769-5] [PMID]

Jiang, Y., Liu, Z., Liao, Y., Sun, S., Dai, Y., & Tang, Y. (2022). Ischemic stroke: From pathological mechanisms to neuroprotective strategies. Frontiers in Neurology, 13, 1013083. [DOI:10.3389/fneur.2022.1013083] [PMID]

Johannessen, C. U. (2000). Mechanisms of action of valproate: A commentatory. Neurochemistry International, 37(2-3), 103-110. [DOI:10.1016/S0197-0186(00)00013-9]

Kanai, H., Sawa, A., Chen, R. W., Leeds, P., & Chuang, D. M. (2004). Valproic acid inhibits histone deacetylase activity and suppresses excitotoxicity-induced GAPDH nuclear accumulation and apoptotic death in neurons. The Pharmacogenomics Journal, 4(5), 336–344. [DOI:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500269] [PMID]

Kim, H. J., Leeds, P., & Chuang, D. M. (2009). The HDAC inhibitor, sodium butyrate, stimulates neurogenesis in the ischemic brain. Journal of Neurochemistry, 110(4), 1226-1240. [DOI:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06212.x] [PMID]

Liu, X. S., Chopp, M., Kassis, H., Jia, L. F., Hozeska-Solgot, A., & Zhang, R. L., et al. (2012). Valproic acid increases white matter repair and neurogenesis after stroke. Neuroscience, 220, 313-321. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.06.012] [PMID]

Mann Brukner, A., Ben-Hur, T., Honig, A., Ekstein, D., & Eyal, S. (2018). Effects of valproic acid on cerebral nutrient carriers’ expression in the rat. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9, 1054. [DOI:10.3389/fphar.2018.01054] [PMID]

Moralí, G., Letechipía-Vallejo, G., López-Loeza, E., Montes, P., Hernández-Morales, L., & Cervantes, M. (2005). Post-ischemic administration of progesterone in rats exerts neuroprotective effects on the hippocampus. Neuroscience Letters, 382(3), 286-290. [DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2005.03.066] [PMID]

Moroni, R. F., Inverardi, F., Regondi, M. C., Panzica, F., Spreafico, R., & Frassoni, C. (2008). Altered spatial distribution of PV‐cortical cells and dysmorphic neurons in the somatosensory cortex of BCNU‐treated rat model of cortical dysplasia. Epilepsia, 49(5), 872-887. [DOI:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01440.x] [PMID]

Naseh, M., Bayat, M., Akbari, S., Vatanparast, J., Shabani, M., & Haghighi, A. B., et al. (2022). Neuroprotective effects of sodium valproate on hippocampal cell and volume, and cognitive function in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. Physiology & Behavior, 251, 113806. [DOI:10.1016/j.physbeh.2022.113806] [PMID]

Naseh, M., Dehghanian, A., Keshtgar, S., & Ketabchi, F. (2020). Lung injury in brain ischemia/reperfusion is exacerbated by mechanical ventilation with moderate tidal volume in rats. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 319(2), R133-R141. [DOI:10.1152/ajpregu.00367.2019] [PMID]

Naseh, M., Dehghanian, A., & Ketabchi, F. (2020). Vagotomy improves hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in rats subjected to brain ischemia-reperfusion injury. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences, 45(4), 250-258. [PMID]

Nishi, T., Maier, C. M., Hayashi, T., Saito, A., & Chan, P. H. (2005). Superoxide dismutase 1 overexpression reduces MCP-1 and MIP-1α expression after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 25(10), 1312-1324. [DOI:10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600124] [PMID]

Pang, T., Wang, Y. J., Gao, Y. X., Xu, Y., Li, Q., & Zhou, Y. B., et al. (2016). A novel GSK-3β inhibitor YQ138 prevents neuronal injury induced by glutamate and brain ischemia through activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 37(6), 741–752. [DOI:10.1038/aps.2016.3] [PMID]

Paxinos, G., Watson, C. (2007). The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates: Hard cover edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. [Link]

Rekling, J. C. (2003). Neuroprotective effects of anticonvulsants in rat hippocampal slice cultures exposed to oxygen/glucose deprivation. Neuroscience Letters, 335(3), 167-170. [DOI:10.1016/S0304-3940(02)01193-X] [PMID]

Shao, L., Young, L. T., & Wang, J. F. (2005). Chronic treatment with mood stabilizers lithium and valproate prevents excitotoxicity by inhibiting oxidative stress in rat cerebral cortical cells. Biological Psychiatry, 58(11), 879-884. [DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.052] [PMID]

Silva, M. R., Correia, A. O., Dos Santos, G. C. A., Parente, L. L. T., de Siqueira, K. P., & Lima, D. G. S., et al. (2018). Neuroprotective effects of valproic acid on brain ischemia are related to its HDAC and GSK3 inhibitions. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 167, 17-28. [DOI:10.1016/j.pbb.2018.02.001] [PMID]

Terzioğlu Bebitoğlu, B., Oğuz, E., & Gökçe, A. (2020). Effect of valproic acid on oxidative stress parameters of glutamate-induced excitotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 20(2), 1321-1328. [DOI:10.3892/etm.2020.8802] [PMID]

Wang, Z., Leng, Y., Tsai, L. K., Leeds, P., & Chuang, D. M. (2011). Valproic acid attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in a rat model of transient focal cerebral ischemia: The roles of HDAC and MMP-9 inhibition. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 31(1), 52-57. [DOI:10.1038/jcbfm.2010.195] [PMID]

Wang, Z., Tsai, L. K., Munasinghe, J., Leng, Y., Fessler, E. B., & Chibane, F., et al. (2012). Chronic valproate treatment enhances postischemic angiogenesis and promotes functional recovery in a rat model of ischemic stroke. Stroke, 43(9), 2430–2436. [DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.652545] [PMID]

Xuan, A., Long, D., Li, J., Ji, W., Hong, L., & Zhang, M., et al. (2012). Neuroprotective effects of valproic acid following transient global ischemia in rats. Life Sciences, 90(11-12), 463-468. [DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2012.01.001] [PMID]

Zhu, S., Zhang, Z., Jia, L. Q., Zhan, K. X., Wang, L. J., & Song, N., et al. (2019). Valproic acid attenuates global cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in gerbils via anti-pyroptosis pathways. Neurochemistry International, 124, 141–151. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuint.2019.01.003] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Cellular and molecular Neuroscience

Received: 2025/03/11 | Accepted: 2025/08/31 | Published: 2025/11/7

Received: 2025/03/11 | Accepted: 2025/08/31 | Published: 2025/11/7

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |