Volume 16, Issue 6 (November & December 2025)

BCN 2025, 16(6): 1097-1112 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Houshmandi N, Azizi H, Shojaei A, Semnanian S. Altered Pain, Emotion, and Stress in Adulthood: Neurobehavioral and Neuroendocrine Consequences of Adolescent Morphine Exposure. BCN 2025; 16 (6) :1097-1112

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3299-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3299-en.html

1- Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. & Institute for Brain and Cognition, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. & Institute for Brain and Cognition, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Adolescent morphine exposure, Emotional behaviors, Pain sensitivity, Corticosterone, Behavioral and neuroendocrine correlations

Full-Text [PDF 1102 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

Introduction

Opioids account for approximately 70% of the global burden of adverse health outcomes associated with drug use disorders (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2018). Adolescents and young adults (aged 12-25) are more susceptible to misusing prescription opioids and engaging in illicit opioid use than other age groups (National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2018). Adolescence is a critical developmental window, often marked by increased impulsivity and risk-taking behaviors (Salmanzadeh et al., 2021; Spear, 2000). This developmental stage confers heightened vulnerability to substance experimentation and increases the risk of developing substance-use disorders (Chambers et al., 2003; Salmanzadeh et al., 2020; Wagner & Anthony, 2002). Understanding the long-term consequences of opioid exposure during adolescence is essential for designing effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that morphine exposure during adolescence induces long-lasting alterations in pain modulation and opioid responsiveness. Specifically, adolescent morphine administration accelerated the development of tolerance to its antinociceptive effects and increased the excitability of neurons in the lateral paragigantocellularis (LPGi) region (Salmanzadeh et al., 2017; Samanzadeh et al., 2018). Furthermore, rats exposed to morphine during adolescence exhibited heightened pain sensitivity in adulthood, with significantly elevated pain scores across all phases of the formalin test compared to controls (Ghasemi et al., 2019). Recently, our findings revealed that adolescent morphine exposure exacerbated both allodynia and hyperalgesia in adulthood under both baseline and neuropathic pain conditions (Alami et al., 2025). These findings collectively suggest that opioid exposure during sensitive periods of neurodevelopment can induce persistent changes in both pain sensitivity and opioid efficacy.

Epidemiological studies have shown a strong relationship between opioid use disorders and the later development of mood disorders (Grant et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 2003; Kessler et al., 2005; Regier et al., 1990). We previously observed that chronic morphine exposure during adolescence reduces anxiety-like behavior in adulthood, as assessed using the open field and elevated plus maze (Khani et al., 2022). In the present study, we utilized the elevated zero maze (EZM), which offers methodological advantages over the traditional elevated plus maze by removing the ambiguous central zone and allowing continuous exploration, to more accurately assess anxiety-related behavior.

Anxiety and emotional regulation are closely associated with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the stress response via glucocorticoid secretion. The endogenous opioid system modulates HPA axis activity through both inhibitory and excitatory pathways (Odio & Brodish, 1990). Dysregulation of the HPA axis has been implicated in mood and anxiety disorders (Holsboer & Ising, 2010; Kammerer et al., 2006). Pharmacological studies have shown that mu-opioid receptor agonists, such as morphine, reduce anxiety, whereas antagonists tend to produce anxiogenic effects (Asakawa et al., 1998; Kõks et al., 1998; Tsuda et al., 1996; Zarrindast et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 1996). Notably, prior research suggests that adolescent morphine exposure may induce long-lasting, sex specific alterations in HPA axis function, even across generations (Vassoler et al., 2014; Vassoler et al., 2018).

To address existing gaps in the literature, the present study is the first to evaluate plasma corticosterone levels in adulthood following adolescent morphine exposure. Importantly, this study uniquely assessed behavioral profiles, including pain sensitivity, anxiety-like behavior, depression-like behavior, and corticosterone levels within the same animals. This was integrated within the subject design, enabling the investigation of potential associations between behavioral and neuroendocrine outcomes, providing a more integrated understanding of the long-term effects of adolescent opioid exposure on emotional behavior, stress regulation, and nociceptive processing. Identifying multidimensional behavioral patterns associated with adolescent morphine exposure remains challenging. While individual behavioral tests provide limited insight, multivariate approaches, such as principal component analysis (PCA), allow detection of integrated behavioral changes that persist into adulthood. This study also investigated whether morphine administration during adolescence produces distinguishable adult behavioral signatures, which could improve understanding of the long-term effects of morphine exposure on behavioral profile.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats were obtained on postnatal day (PND) 23 from the Razi Institute (Tehran, Iran) and housed in groups of four under controlled conditions (12-hour light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water). The animals were allowed to acclimate for one week before the experimental procedures. All protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran, and conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Experimental procedure

To reduce stress, rats were gently handled daily during the acclimation period.

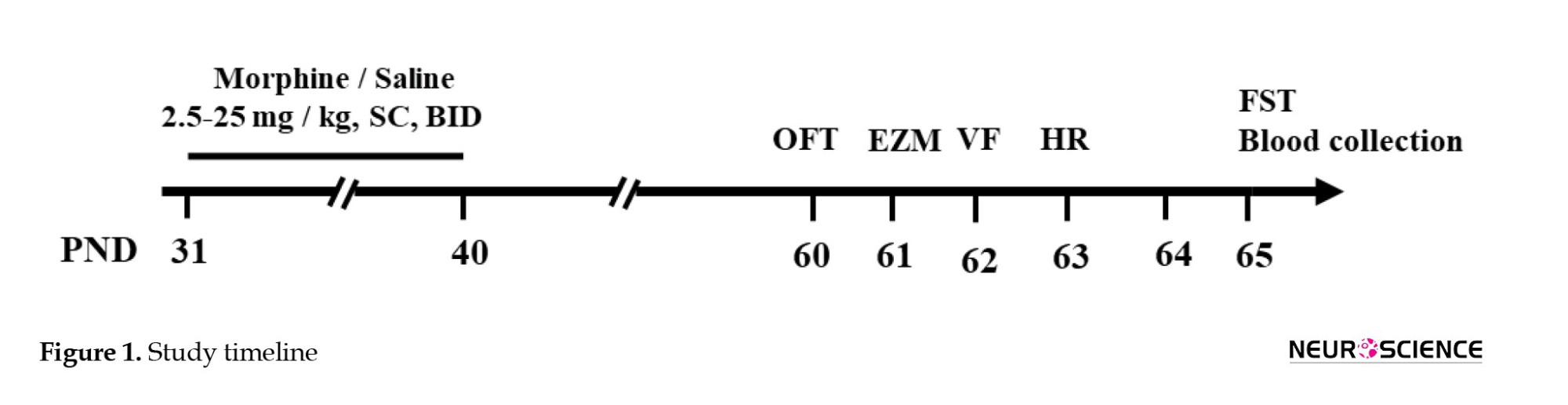

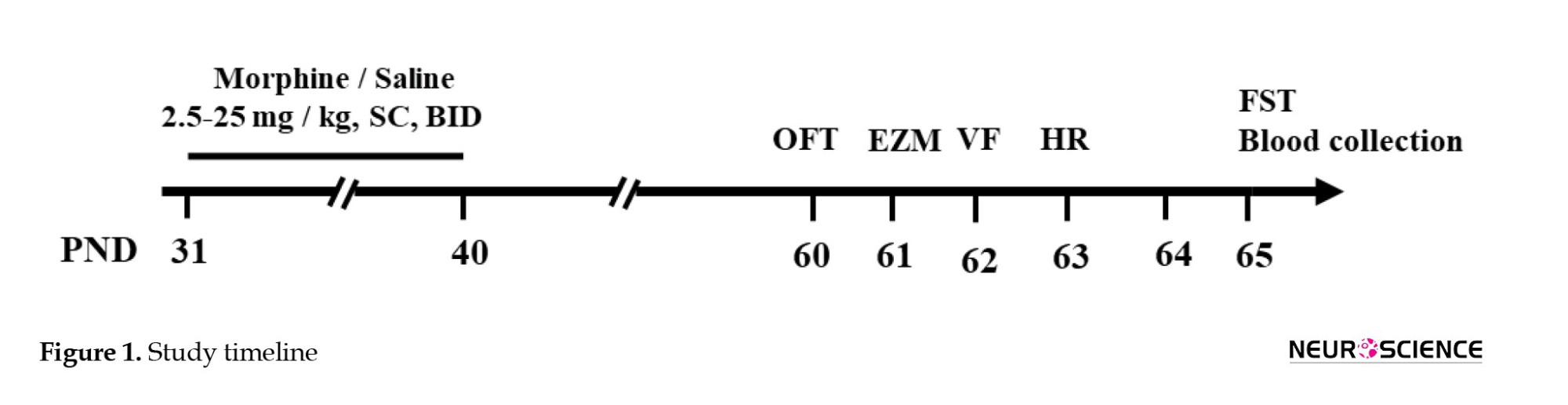

Beginning on PND 31, adolescent rats received subcutaneous (s.c.) injections of morphine sulfate (Temad, Tehran, Iran) twice daily (08:00 and 20:00) for 10 consecutive days. Morphine was administered according to an escalating dose regimen of 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 17.5, 20, 22.5, and 25 mg/kg. For each injection, the appropriate dose was freshly prepared by dissolving morphine in 2 mL of sterile normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride [NaCl]) immediately prior to administration. Age-matched control animals were administered equivalent volumes of saline using the same injection schedule. After the final injection, all animals remained drug-free for a 20-day washout period. Behavioral assessments were conducted between PND 60 and 65 (Figure 1).

Behavioral experiments

Open field test (OFT)

The OFT was used to evaluate anxiety-related behaviors. The testing apparatus comprised a black Plexiglass square arena (measuring 60×60×60 cm) with its floor divided into 16 squares by virtual lines, delineating the central and peripheral areas. The rats were placed in the central part of the arena and given five minutes to explore their surroundings freely. The rat’s movements were observed and documented using a video-tracking system (EthoVision software,version 9; Noldus Information Technology, Netherlands). Locomotor activity was assessed by recording the distance travelled over 5 minutes. Additionally, the duration the animal spent in the center of the open field was measured to assess anxiety-like behaviors (Walsh & Cummins, 1976). After each test, the arena was cleaned with 70% ethanol.

EZM test

The EZM consisted of a circular platform made of black Perspex. The platform had a diameter of 105 cm and a width of 10 cm. It was elevated 65 cm above the ground and divided into four quadrants. Each rat was initially placed in the central region of the enclosed square during the 10-minute testing period. After each testing session, the maze is sanitized with 70% ethanol and left to air dry. The animal’s movements within the maze were recorded using an overhead camera and subsequently analyzed with a tracking system (EthoVision XT, version 9; Noldus Information Technology, Netherlands). The key behavioral parameters included the number of entries into each arm and the duration of time spent in each arm (Shepherd et al., 1994).

Von-Frey (VF) test

Mechanical pain sensitivity was evaluated using VF filaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA) applied to the plantar surface of the hind paw, according to the up–down method outlined by Chaplan et al. (1994). Animals were placed individually in transparent acrylic enclosures on a 30 cm-high elevated wire-mesh platform (11×12×20 cm) to allow access to the paw. Prior to testing, the rats were habituated to the apparatus for 15 minutes. A collection of 10 VF filaments, with stiffness values increasing logarithmically (0.4, 0.6, 1, 1.4, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 26 g), was employed. During the test, each filament was applied perpendicularly to the mid-plantar region of both paws until it bent, and held for 2–5 s. Each filament was presented five times, and the withdrawal responses were recorded to determine mechanical sensitivity.

Hargreaves test

The latency of paw withdrawal in response to thermal stimuli was measured using radiant heat with a Hargreaves apparatus (IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, CA, USA). Unrestrained animals were placed in Plexiglass containers (11×12×20 cm) and allowed to acclimate for 15 minutes. Subsequently, a radiant heat source was applied to the plantar surface of both hind paws. The testing device was set to approximately 55% of its maximum power. Thermal response latencies were documented across three distinct trials, each conducted at a 5-minute interval. The mean of these three measurements was determined as the paw withdrawal latency (PWL). A maximum cut-off duration of 20 s was implemented to avert potential tissue damage (Hargreaves et al., 1988).

Forced swimming test (FST)

The FST was a two-day testing process. During the pre-test session, rats were individually submerged in a glass cylinder (95 cm high and 15.5 cm in diameter) filled with 30 cm of water maintained at 23-24 °C for 15 minutes. The next day, these rats were subjected to a 5-minute test session. The experiment’s testing section was monitored and assessed by an unbiased observer using a computer-based event recording system. Following the FST, rats were towel-dried and returned to their home cages, which were maintained for approximately 20 minutes to aid recovery (Porsolt et al., 1977).

Blood collection and corticosterone measurement

Thirty minutes following the completion of the 6-minute FST, the rats were decapitated, and trunk blood was collected into sterile Eppendorf tubes (Connor et al., 1997). Samples were immediately placed on ice, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C, and the resulting serum was stored at −80 °C until analysis. Serum corticosterone concentrations were determined using a commercially available ELISA kit (Cat. No: CSB-E05112r; Cusabio, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 µL of serum was added to 100 µL of enzyme conjugate per well, and the plate was incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer. The assay demonstrated good precision, with intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation below 8% and 10%, respectively. Corticosterone levels were calculated using a standard curve constructed from serial dilutions ranging from 3.12 to 200 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 1.56 ng/mL.

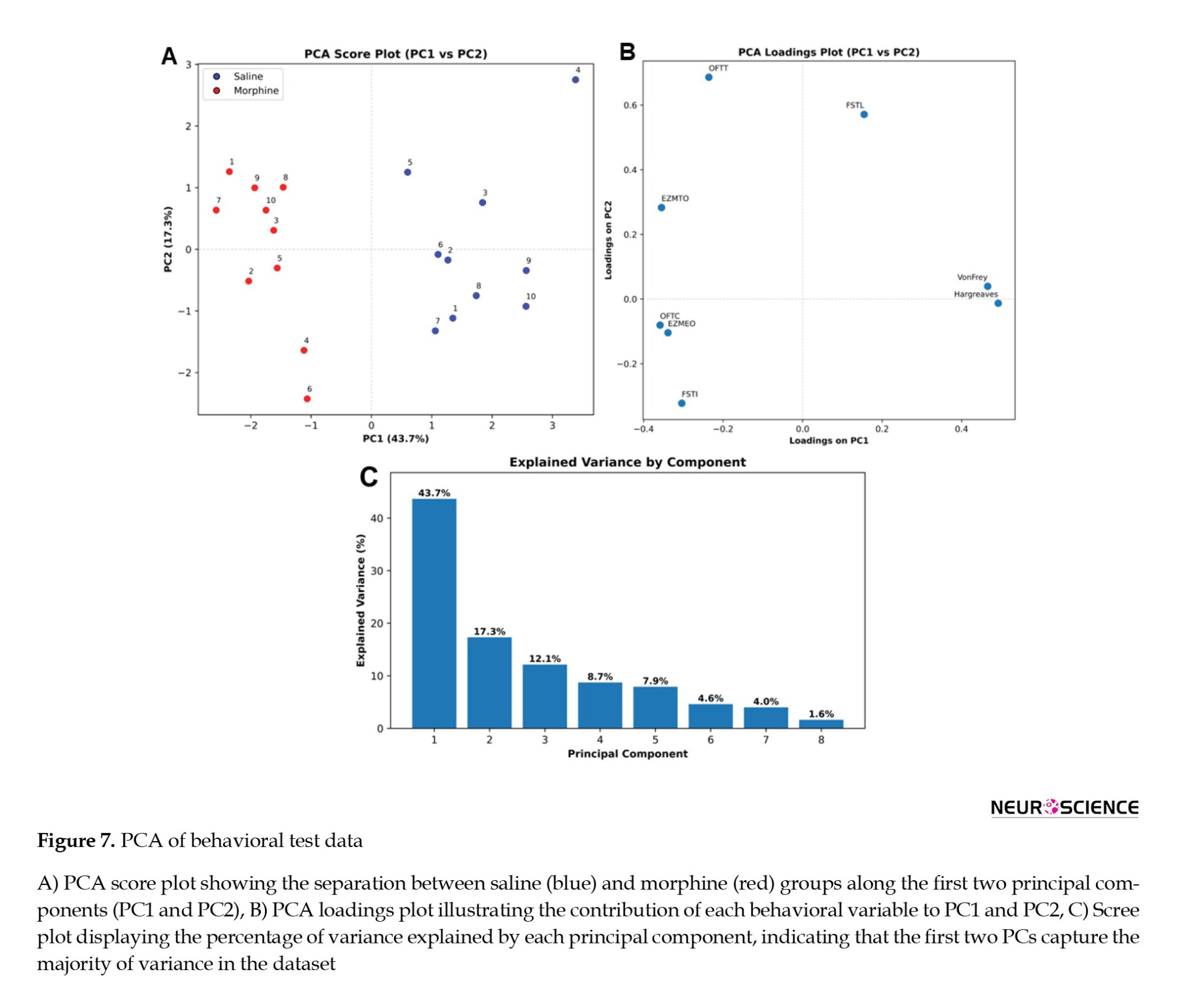

Behavioral PCA

Adult rodents previously treated with morphine or saline during adolescence were evaluated across multiple behavioral assays, including the OFT, EZM, VF, Hargreaves, and FST. Eight behavioral measures were standardized using Z-scores and analyzed using PCA to reduce dimensionality and identify principal components capturing maximal variance. PCA scores and loadings were visualized to examine treatment-specific clustering and the contribution of each behavioral measure to the principal components (Python 3.13.5, Anaconda Distribution, Anaconda Inc).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software, version 7. Data are expressed as Mean±SEM, with a P<0.05 indicating statistical significance. Data distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. For datasets exhibiting normal distributions, an unpaired student’s t-test was employed, whereas the Mann–Whitney U test was utilized for datasets not conforming to this distribution.

Results

Adolescent morphine exposure effects on anxiety-like behavior in adulthood

From PND 31 to 40, adolescent rats were subjected to chronic morphine exposure for 10 consecutive days. To assess anxiety-like behavior, behavioral testing was conducted on PND 60 and 61 using the OFT and EZM (Figure 1).

Treatment and behavioral testing

Rats were administered either saline or morphine during adolescence (PNDs 31–40). Between PNDs 60 and 65, a series of behavioral tests were conducted to assess long-term effects. Anxiety-like behavior was evaluated using the OFT and EZM, while pain sensitivity was assessed with the VF and Hargreaves tests. Depression-like behavior was examined using the FST, followed by blood collection for corticosterone level measurement.

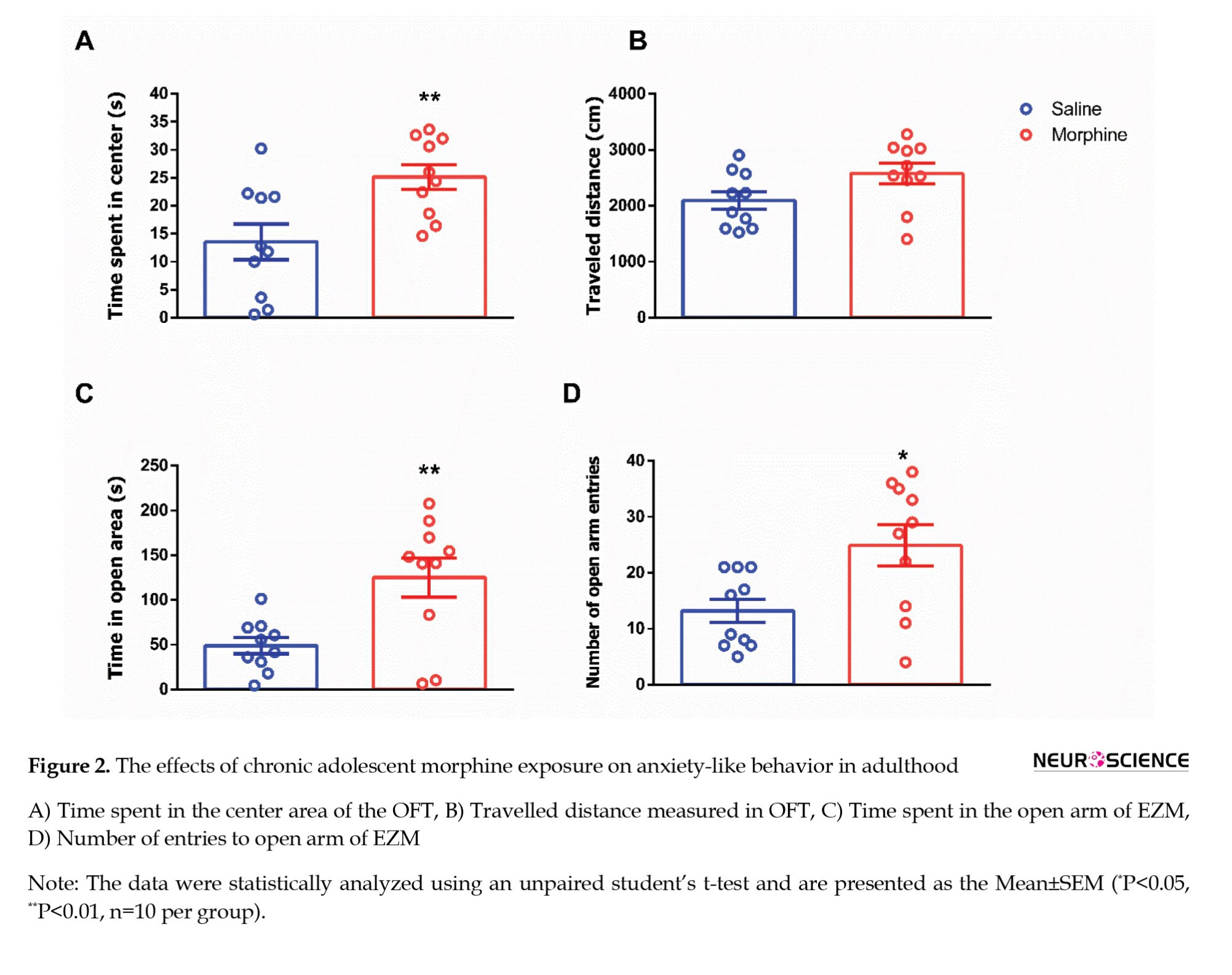

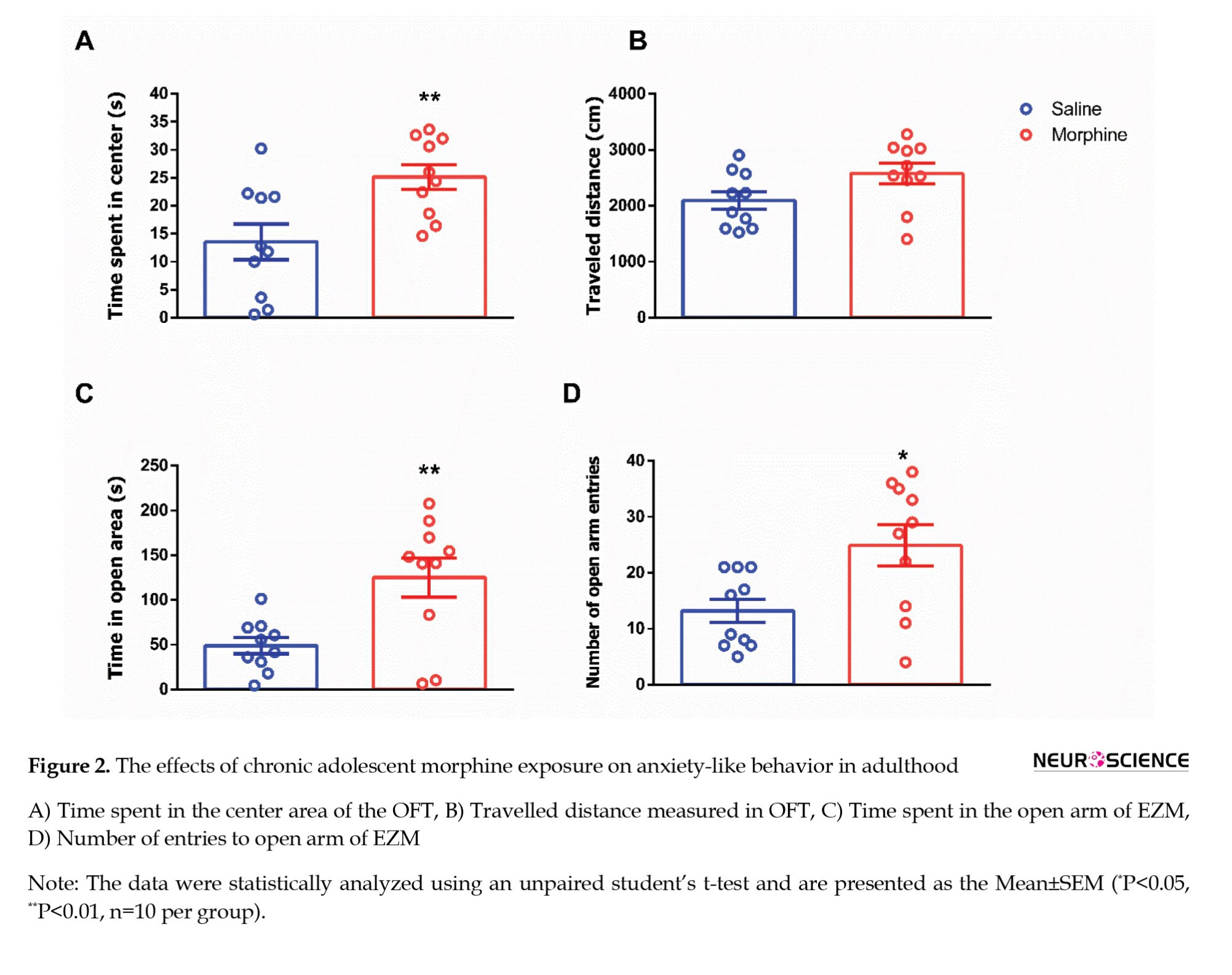

In the OFT, morphine-exposed rats spent significantly more time in the center of the arena than saline-treated controls (t=2.982, P=0.0080; Figure 2A), suggesting reduced anxiety-like behavior. However, no significant difference was observed in the total distance travelled between the two groups (t=1.993, P=0.0616; Figure 2B), indicating that locomotor activity was not affected. Anxiety-like behavior was further evaluated using the EZM test. Rats exposed to morphine during adolescence spent more time in the open arms (t=3.207, P=0.0076; Figure 2C) and made significantly more entries into the open arms (Mann-Whitney U=20, P=0.0221; Figure 2D) compared to the saline group, further supporting an anxiolytic-like effect of adolescent morphine exposure.

Adolescent morphine exposure effects on pain thresholds in adulthood

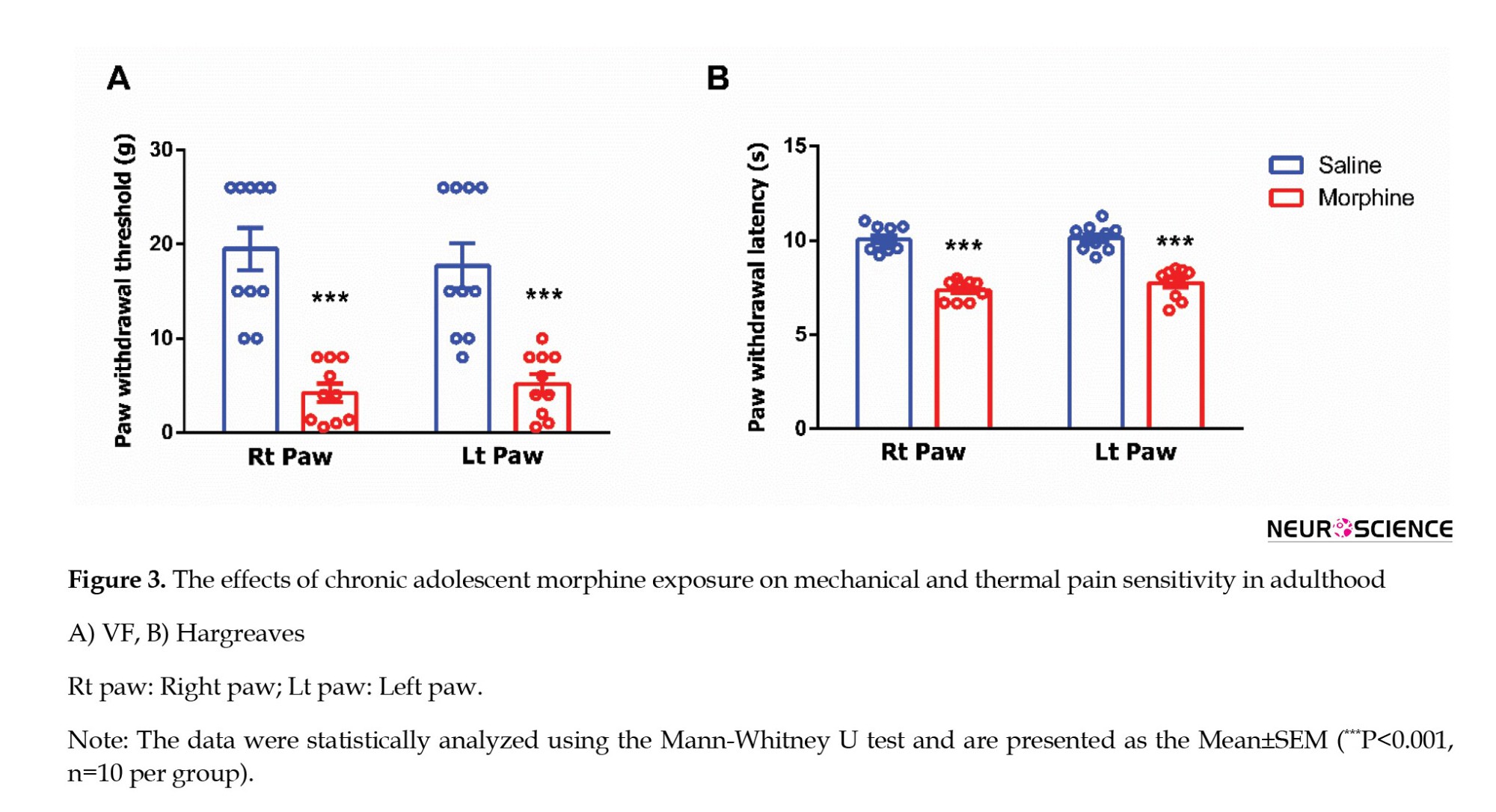

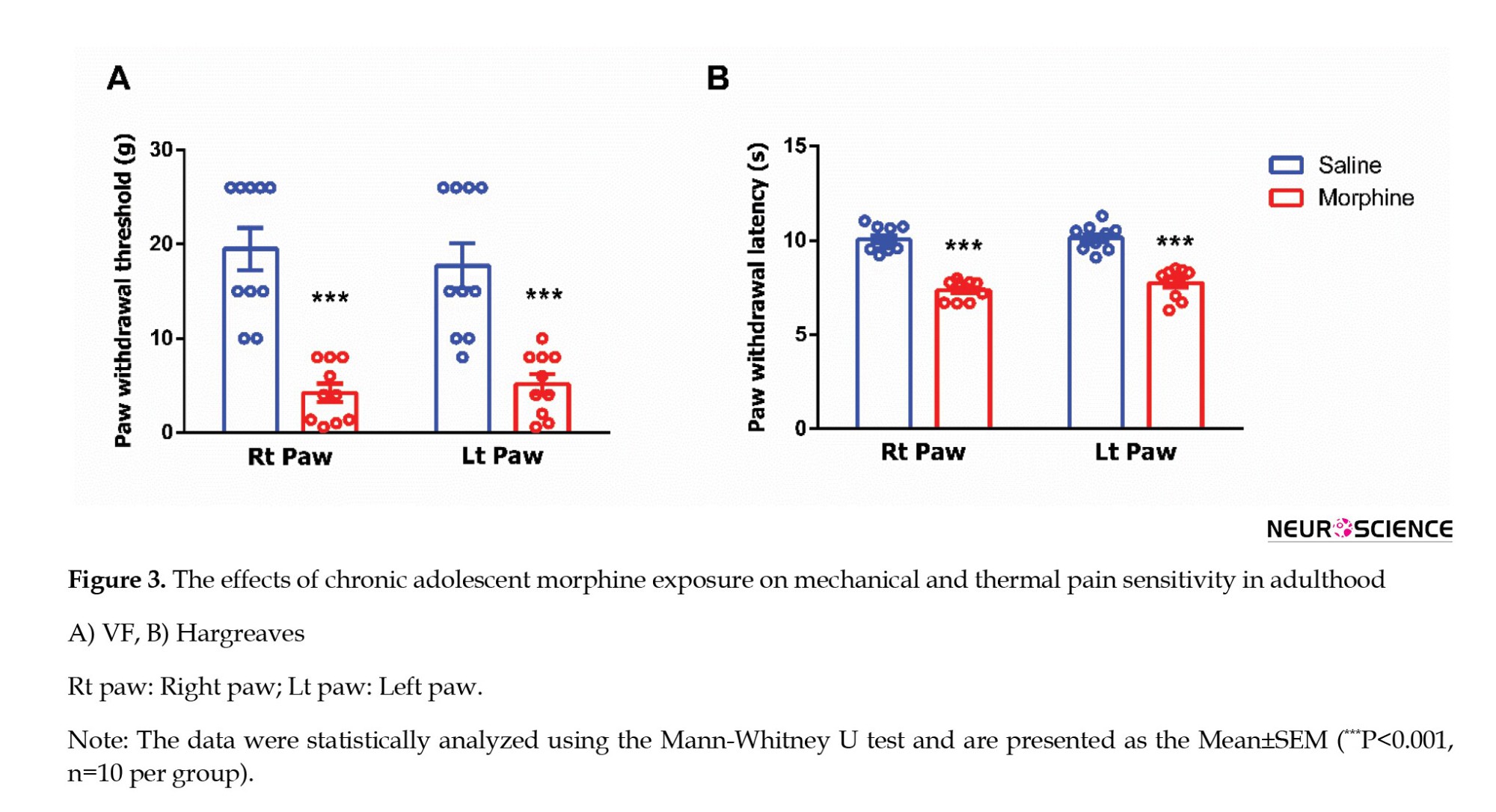

Next, we assessed mechanical allodynia, defined as abnormal sensitivity to non-noxious mechanical stimuli, and thermal hyperalgesia, characterized by an intensified response to noxious thermal stimuli, on PNDs 62 and 63 (Figure 1). Mechanical allodynia was evaluated using the VF filament test. Adolescent rats exposed to morphine exhibited a significantly reduced threshold for tactile sensitivity in both hind paws compared to saline-treated controls (right paw: Mann-Whitney U=0, P<0.0001; left paw: Mann-Whitney U=3.5, P=0.0001; Figure 3A). Thermal nociception was assessed using the Hargreaves test to determine the effects of morphine exposure during adolescence. Morphine-treated rats demonstrated significantly decreased paw withdrawal latencies in both hind paws relative to the saline group, indicating heightened thermal sensitivity (right paw: Mann-Whitney U=0, P<0.0001; left paw: Mann-Whitney U=0, P<0.0001; Figure 3B).

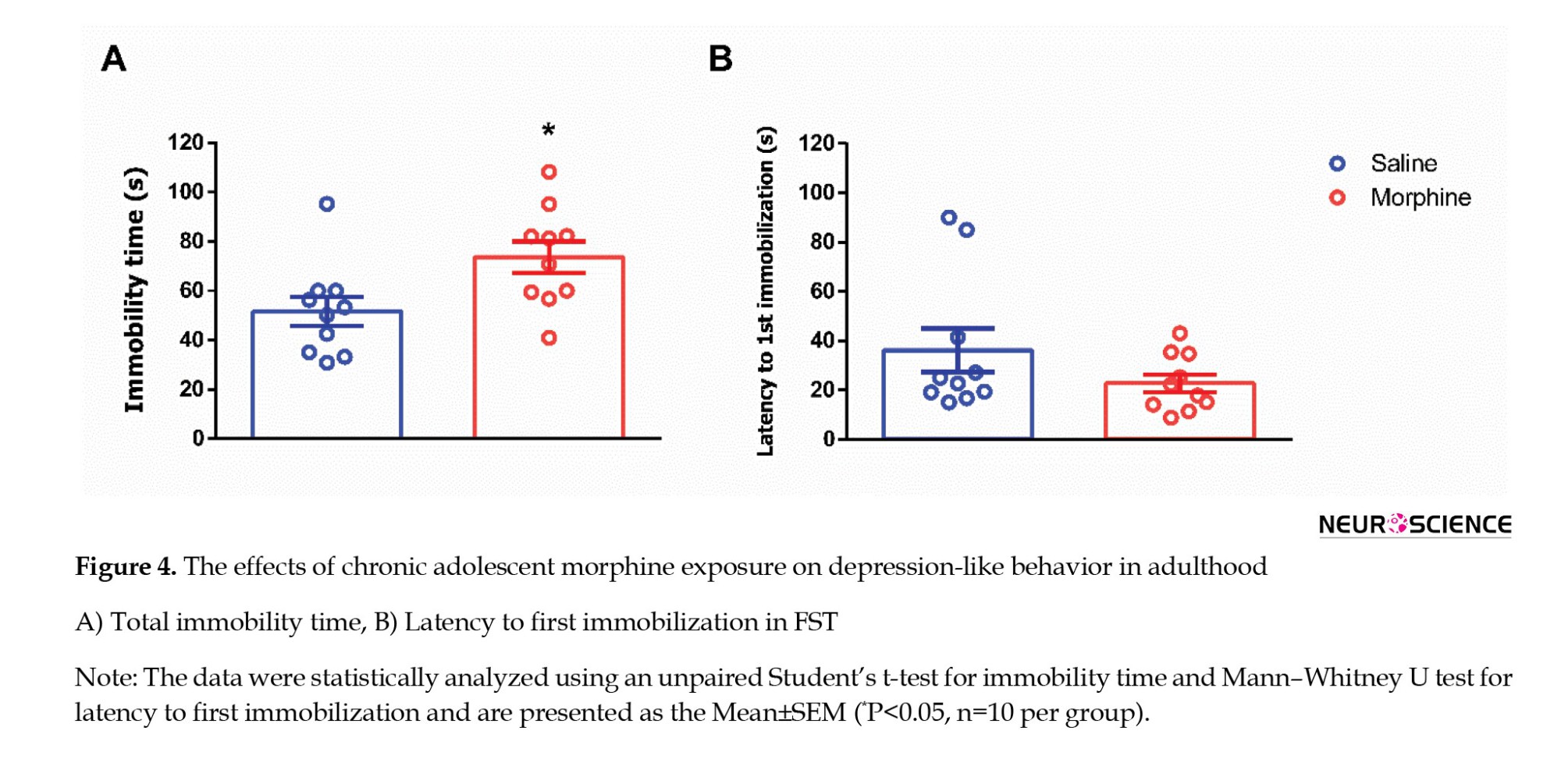

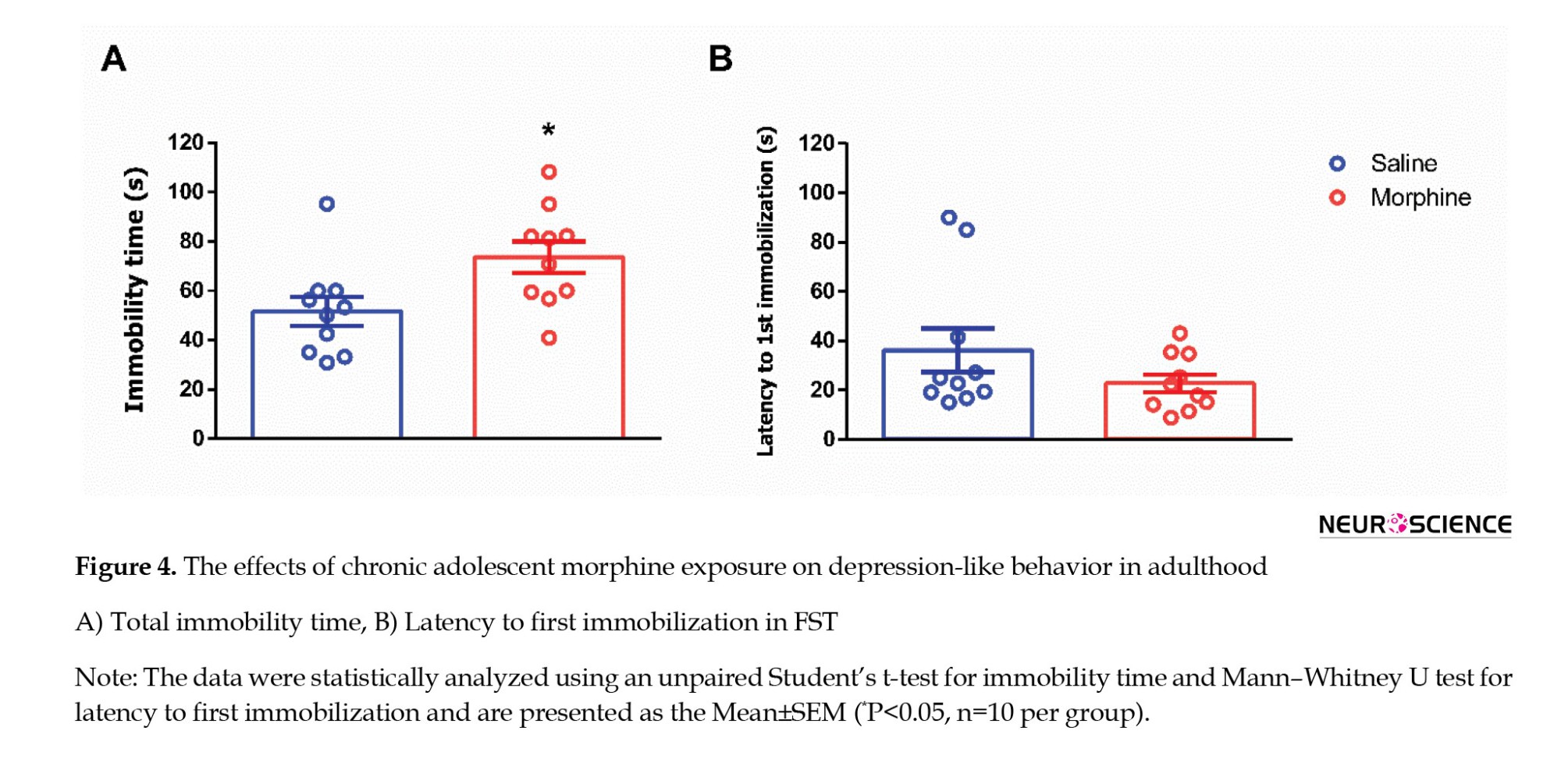

Adolescent morphine exposure effects on depression-like behavior in adulthood

Depression-like behavior was evaluated using the FST on PND 65 (Figure 1). Animals exposed to morphine during adolescence exhibited a significant increase in total immobility time compared to saline-treated controls (t=2.528, P=0.0210; Figure 4A), indicating enhanced behavioral despair. In contrast, no significant difference was observed between the groups in latency to first immobility (Mann–Whitney U=35, P=0.2761; Figure 4B).

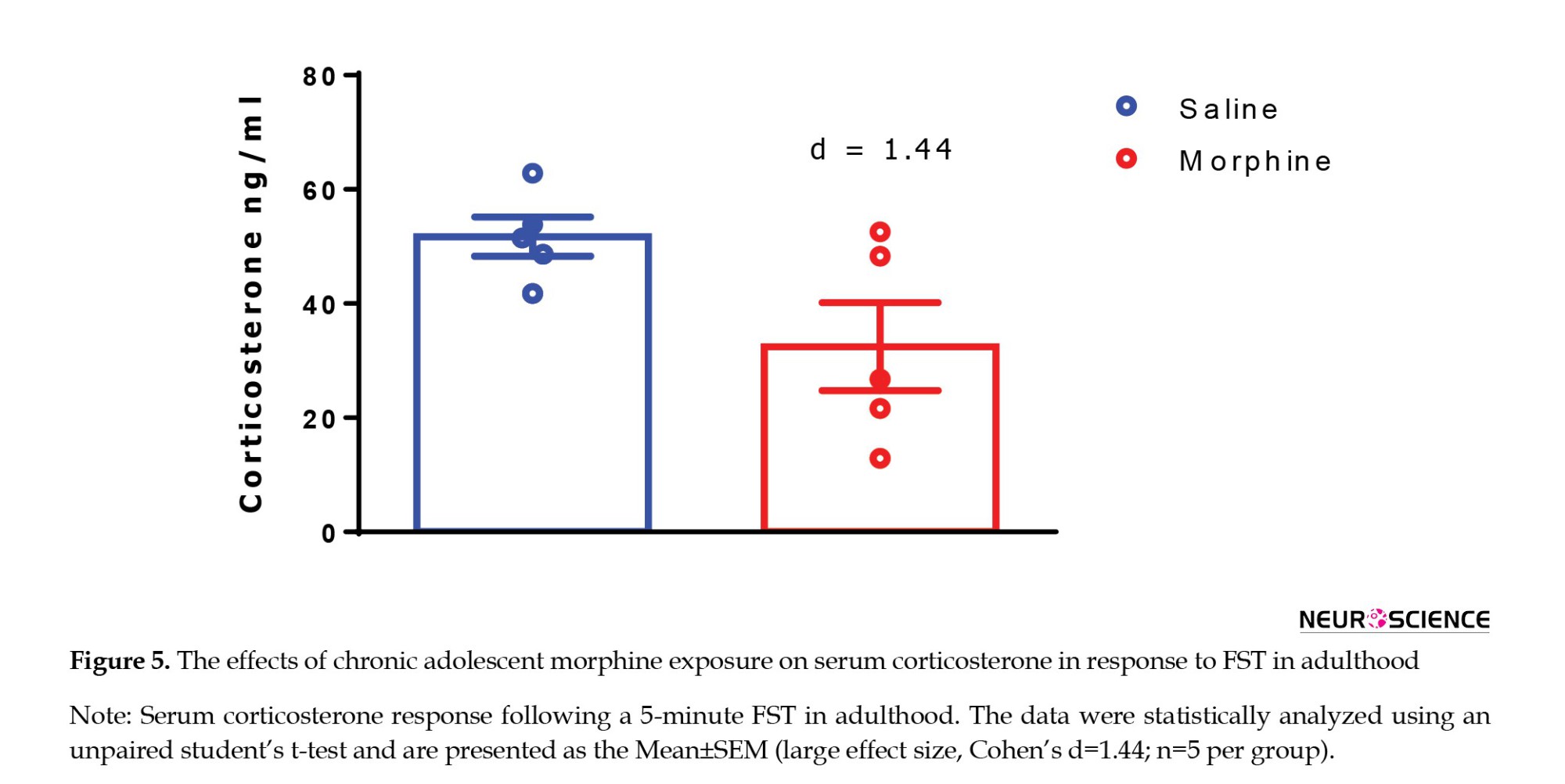

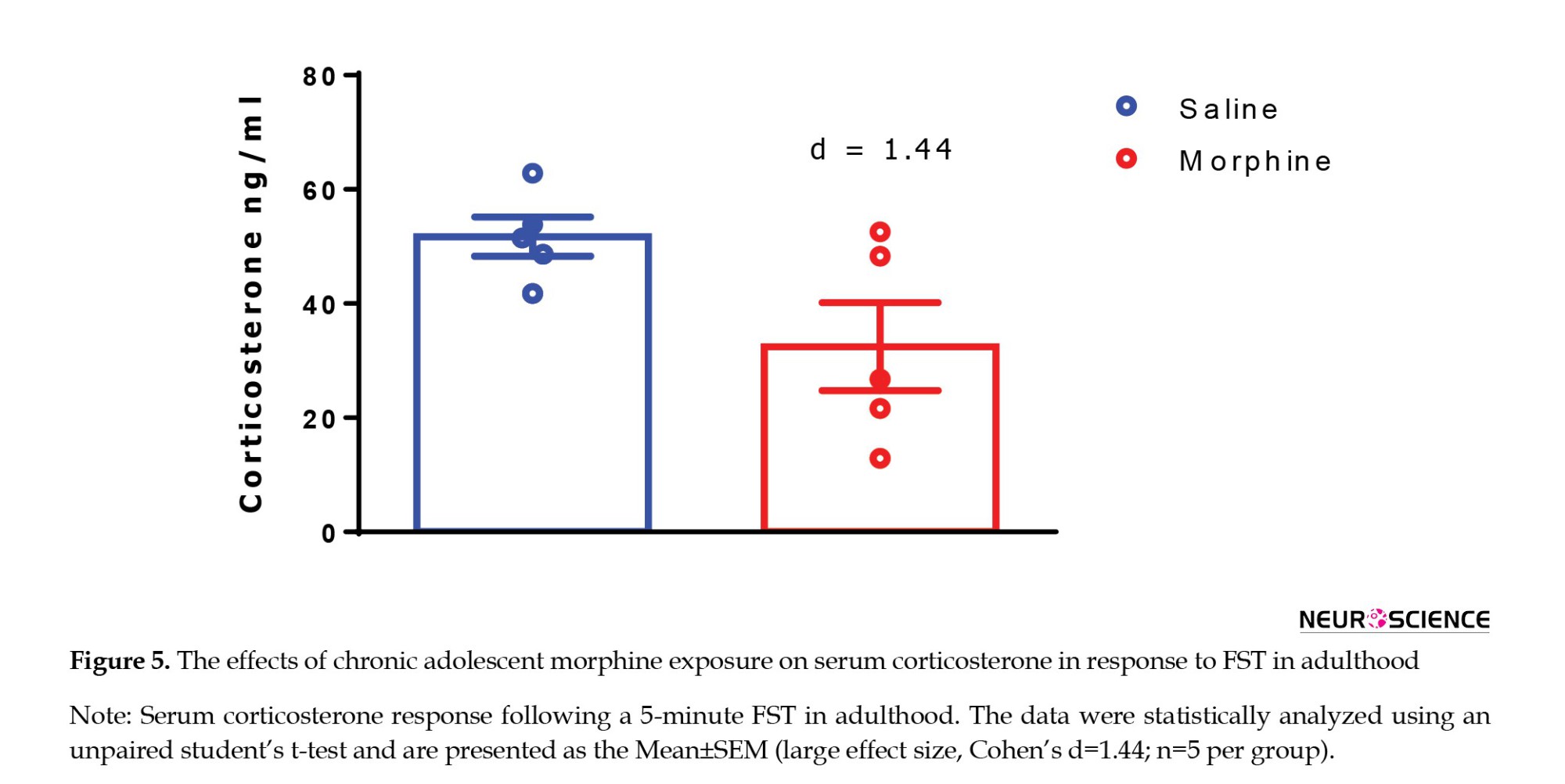

Adolescent morphine exposure effects on serum corticosterone level in adulthood

Following the FST, we measured serum corticosterone levels to assess the physiological stress response. Our analysis revealed a reduction in corticosterone concentrations in adolescent rats treated with morphine compared to those treated with saline. However, this difference was not statistically significant (t=2.282, P=0.0663; Figure 5), but the magnitude of the difference showed a large effect size (Cohen’s d=1.44), suggesting that chronic morphine exposure during adolescence may markedly attenuate HPA axis responsiveness in adulthood.

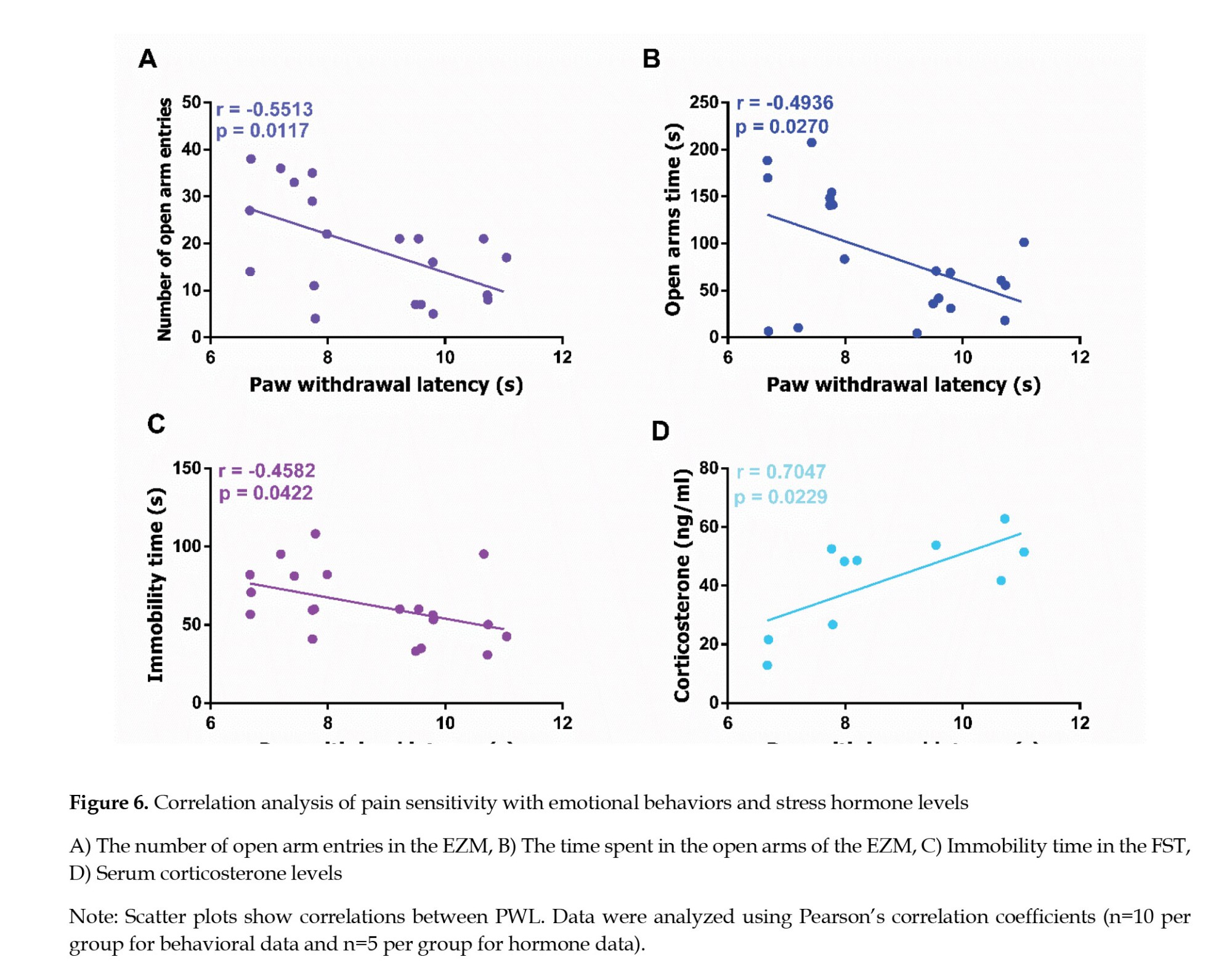

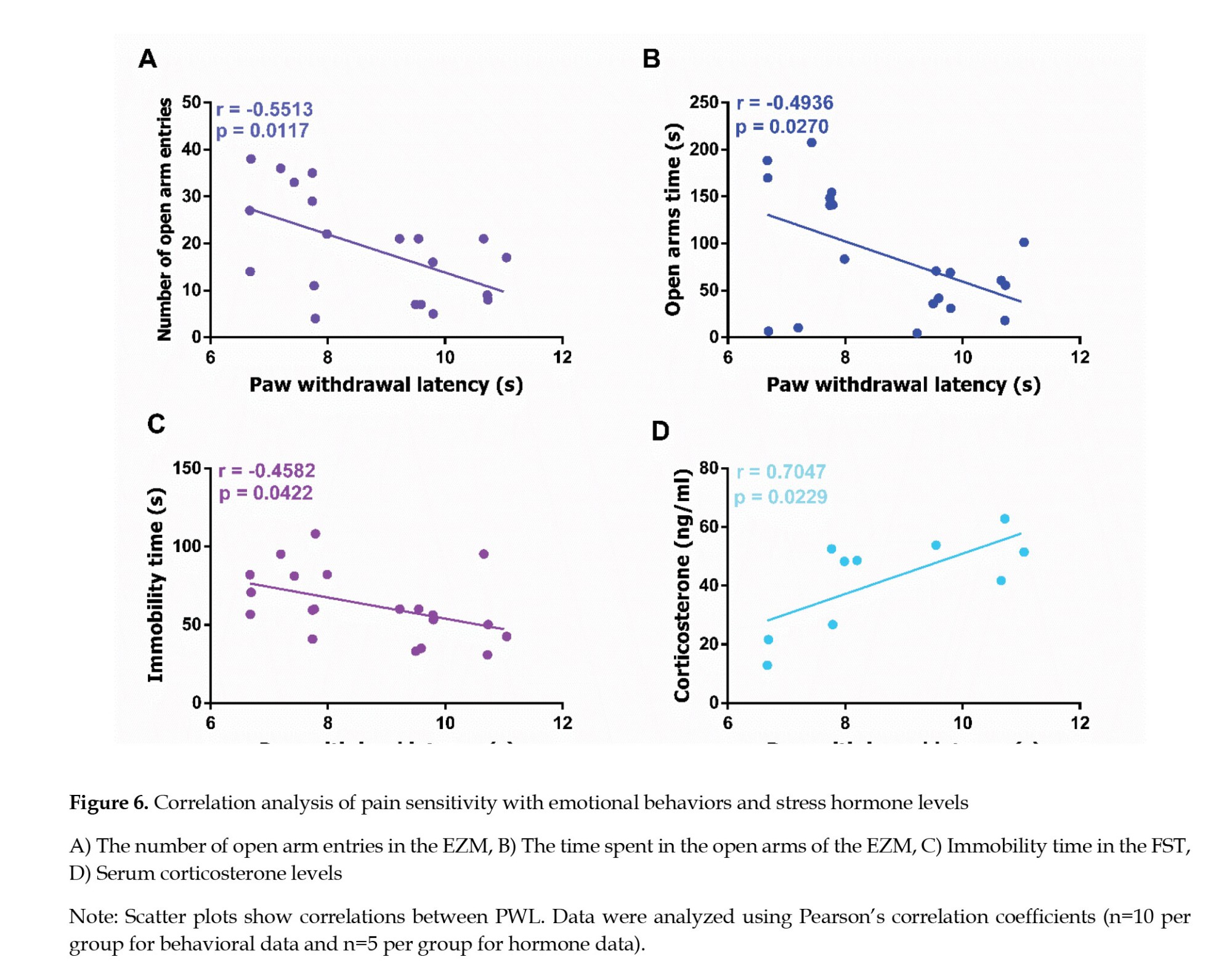

Correlation between nociceptive sensitivity and behavioral and hormonal stress responses

To investigate the relationship between nociceptive sensitivity and stress-related phenotypes, we conducted correlation analyses between PWL and multiple behavioral and hormonal stress markers. Specifically, we examined the associations between PWL and the following variables: The number of entries into the open arms of the EZM, the duration spent in the open arms of the EZM, serum corticosterone concentrations, and immobility time in the FST. These analyses aimed to determine whether altered pain sensitivity is associated with anxiety-like behavior, HPA axis regulation, and behavioral despair.

PWL demonstrated a significant negative correlation with the number of entries into the open arms of the EZM (r=-0.5513, P=0.0117; Figure 6A), and a significant negative correlation with the duration spent in the open arms (r=-0.4936, P=0.0270; Figure 6B), suggesting that reduced nociceptive sensitivity may be associated with increased anxiety-like behavior. In addition, PWL was significantly negatively correlated with immobility time in the FST (r=–0.4582, P=0.0422; Figure 6C), indicating a potential link between lower pain sensitivity and reduced behavioral despair. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation was observed between PWL and serum corticosterone concentrations (r=0.7047, P=0.0229; Figure 6D), highlighting a possible relationship between pain sensitivity and stress hormone levels.

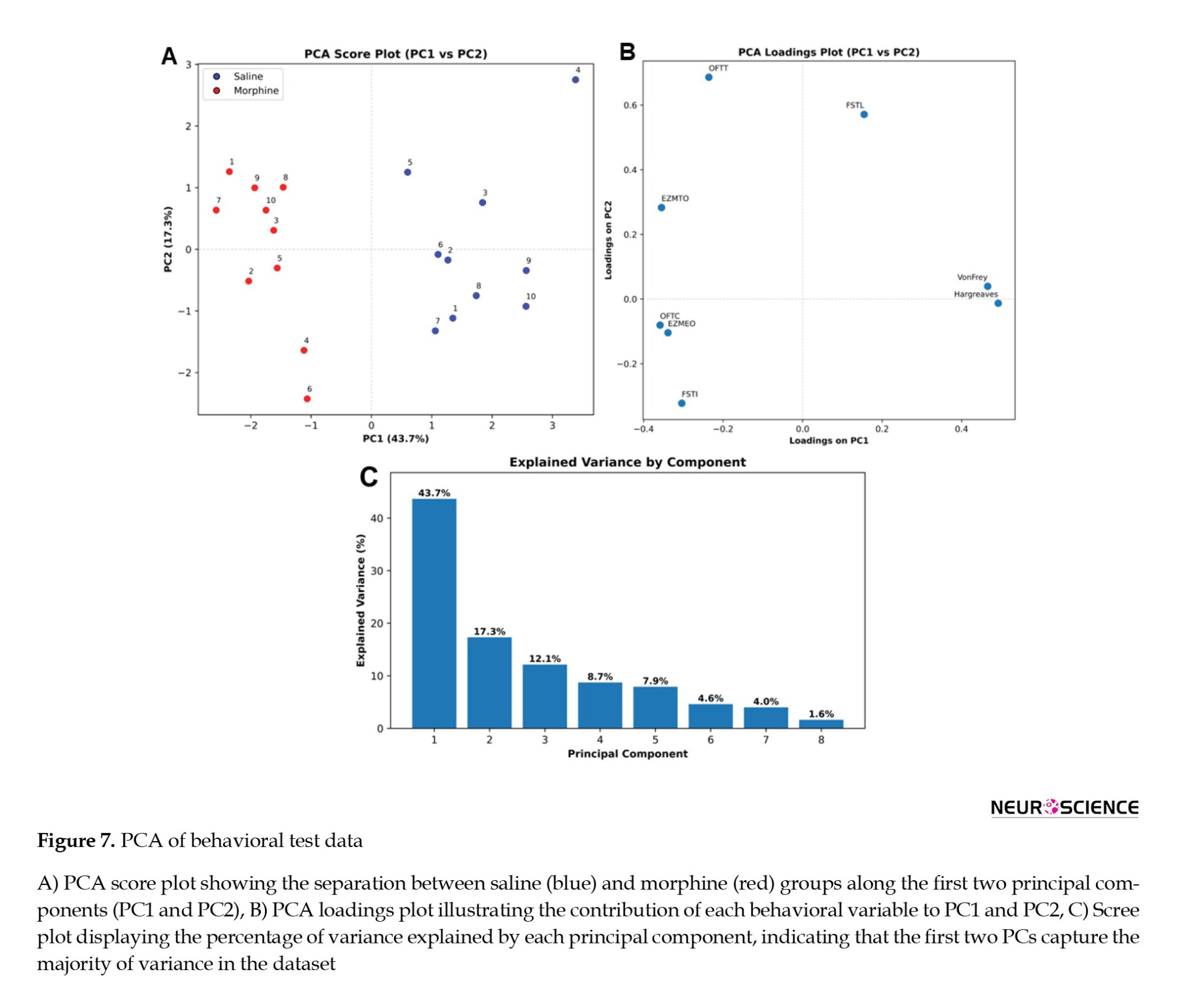

Treatment-specific behavioral profiles revealed by PCA

PCA showed that the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) explained 43.7% and 17.3% of the total variance, respectively (Figure 7C). Morphine-treated animals clustered distinctly from saline-treated controls along PC1 (Figure 7A), demonstrating systematic behavioral differences induced by adolescent morphine exposure. Loading analysis indicated that OFTT (T: Travelled distance), EZMTO (TO: Time spent in the open arm), and FSTL (L: latency to first immobilization) contributed most strongly to PC1, whereas Hargreaves and VF measurements loaded predominantly on PC2 (Figure 7B). These results suggest that adolescent morphine treatment produces separable multidimensional behavioral profiles in adulthood, affecting both OFT/EZM-related parameters and nociceptive measures. Since the number of animals (20 subjects) relative to the number of variables (8 behavioral measures) did not reach the ideal 5:1 ratio, the PCA results were reported as an exploratory analysis and should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that exposure to morphine during adolescence produces enduring behavioral and neuroendocrine disturbances in adulthood. Compared to saline-treated rats, morphine-exposed animals exhibited reduced anxiety-like behavior, heightened pain sensitivity (manifested as both hyperalgesia and allodynia), and increased depression-like responses. The PCA results also demonstrate that adolescent morphine exposure produces a distinct and lasting behavioral profile in adulthood, clearly separating treated animals from saline controls. These findings indicate that morphine influences multiple behavioral domains in a coordinated manner, underscoring the utility of multivariate approaches, such as PCA, for capturing complex treatment-specific patterns that may otherwise go undetected in univariate analyses.

Adolescence represents a critical developmental window during which the opioid system is still maturing, as receptor expression gradually reaches functionally adequate levels (Carretero et al., 2004; Gazyakan et al., 2000; Kivell et al., 2004). Chronic morphine exposure during this period can induce persistent alterations in both mu and kappa opioid receptor systems, which play essential roles in regulating affective states (Byrnes, 2008; Mague et al., 2003). The emotional and anxiety-like behavioral alterations observed following adolescent morphine exposure may be partly attributed to the incomplete development of top-down regulatory systems responsible for behavioral control that are more fully established in adulthood (Casey & Caudle, 2013). These behavioral modifications may be driven by disrupted prefrontal cortex (PFC)–amygdala circuitry (Figueroa et al., 2021), alterations in mesolimbic dopamine signaling, including D1 receptor and tyrosine hydroxylase expression (Bolaños et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2022), and dysregulation of activity-dependent genes involved in synaptic plasticity (e.g. c-Fos and ΔFosB) (Figueroa et al., 2021; Yazdanfar et al., 2021). Our findings are consistent with previous research from our laboratory, which demonstrated similar anxiety-like behavioral changes using the open field and elevated plus maze following adolescent morphine exposure (Khani et al., 2022).

Interestingly, evidence suggests the potential transgenerational effects of adolescent morphine exposure. For example, female rats exposed to morphine during adolescence produced offspring that exhibited reduced anxiety-like behaviors in adulthood, possibly influenced by hormonal cycles and transgenerational mechanisms (Vassoler & Byrnes, 2021). Comparable findings have been reported for other psychostimulants. Adolescent exposure to cocaine (Daws et al., 2011) and methamphetamine (Buck et al., 2017) has been associated with reduced anxiety-like behavior in adulthood, whereas exposure to THC (tetrahydrocannabinol: Cannabinoid receptor agonist) is associated with increased anxiety-like behaviors in adulthood (Higuera-Matas et al., 2009; Llorente-Berzal et al., 2013; Renard et al., 2017). These divergent effects highlight the complexity of drug exposure during adolescence. Notably, Zhu et al. (2016) found that adolescent cocaine administration could also lead to anxiogenic responses in adulthood, while other studies reported no significant long-term effects (Bortolato et al., 2014; Rubino et al., 2008; Sanchez et al., 2016). Such discrepancies underscore the influence of experimental variables, including strain differences, sex, dosage regimens, developmental timing, and duration of drug exposure, all of which can critically shape long-term behavioral outcomes (Azadi et al., 2021).

Consistent with our findings, previous investigations on adolescent morphine exposure have reported no significant differences in total distance traveled or overall activity levels when comparing treated and control animals. This suggests that the observed behavioral changes were specific to anxiety-like responses rather than general locomotor activity (Khani et al., 2022; Vassoler & Byrnes, 2021). The mechanisms underlying these long-lasting alterations appear to involve brain regions critically implicated in emotional regulation, particularly the amygdala and PFC, both of which are susceptible to drug exposure during adolescence (Akwa et al., 1999; Kenwood et al., 2022). Evidence from studies on other psychostimulants supports this view. For instance, adolescent cocaine use has been shown to induce enduring emotional effects by transiently altering gene expression patterns related to synaptic development within the amygdala (Daws et al., 2011). Similarly, adolescent amphetamine exposure disrupts inhibitory signaling in the PFC by interfering with dopamine–GABA interactions (Kang et al., 2016; Paul et al., 2016), and subsequently enhances monoaminergic activity in adulthood (Labonte et al., 2012).

The dopaminergic system, which undergoes heightened activity during adolescence, is particularly vulnerable to drug-induced modifications (Wahlstrom et al., 2010). In parallel, prolonged opioid exposure has been reported to reduce levels of cytoskeletal proteins, such as neurofilaments (NFs), within the PFC (Beitner-Johnson et al., 1992; Boronat et al., 1998; Garcí-Sevilla et al., 1997). Such reductions are thought to contribute to neurotoxicity and cortical degeneration (Jiménez-Romero et al., 2020; Nestler et al., 1996). These structural vulnerabilities in key cortical and limbic circuits may underlie the persistent emotional and behavioral disturbances observed following adolescent morphine exposure.

We observed reduced pain thresholds in adulthood following adolescent morphine exposure. This result is consistent with previous findings from our laboratory, which similarly reported long-lasting alterations in nociceptive processing (Alami et al., 2024; Ghasemi et al., 2019; Pachenari et al., 2018). Our findings align with broader evidence indicating that morphine exposure during early developmental stages produces enduring changes in pain sensitivity. For example, exposure during infancy has been shown to reduce both thermal and mechanical pain thresholds and to enhance formalin-evoked nociceptive behaviors in later life (Nunes et al., 2017; Rozisky et al., 2012). These results suggest that opioid exposure during critical developmental periods may predispose individuals to long-lasting hypersensitivity.

The mechanisms underlying these effects may involve neuroimmune processes, particularly microglial activation and inflammatory signaling (Ho et al., 2020). The toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) has been implicated explicitly in morphine-induced allodynia (Ellis et al., 2016; Green-Fulgham et al., 2019). Notably, inhibiting microglial activation during adolescence has been shown to mitigate hypersensitivity, highlighting this pathway as a potential therapeutic target (Alami et al., 2025).

Persistent nociceptive alterations following adolescent morphine exposure also appear to involve changes in brain regions that regulate pain. Modifications in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG) and LPGi nuclei have been linked to disrupted endogenous opioid signaling and altered neuronal activity (Alami et al., 2024; Salmanzadeh et al., 2018). In addition, our laboratory previously demonstrated that adolescent morphine exposure induces long-lasting alterations in the locus coeruleus, a key brain region involved in pain modulation, and enhances its excitability in subsequent generations (Pachenari et al., 2019).

Our findings of increased pain sensitivity, together with reduced anxiety-like behavior, raise important questions about whether these alterations are also accompanied by changes in depression-like states. Pain processing and emotional regulation share overlapping neural substrates, including the PFC, amygdala, and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), as well as common neuroimmune mechanisms such as microglial activation (Duan et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025). Given these shared pathways, it is plausible that adolescent morphine exposure induces parallel changes across nociceptive and affective domains. Therefore, we evaluated the impact of adolescent morphine exposure on depression-like responses.

Depression-like behavior was assessed using the FST, in which morphine-exposed animals exhibited increased immobility, a well-established marker of behavioral despair. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have reported that adolescent morphine exposure in both mice and rats leads to the emergence of depression-like behavior later in life (Jiménez-Romero et al., 2020; Lutz et al., 2013). These animal models have provided important insights, although most have relied on specific strains and dosing regimens that differ from the approach used in our study. By employing a different rat strain and varying morphine dosages, and durations of exposure, our results expand on the existing literature and highlight the robustness of this behavioral outcome.

Prolonged morphine exposure during adolescence disrupts the normal development of neural circuits involved in emotional regulation, particularly within the PFC. This disruption is associated with neurotoxic effects, including reductions in NF proteins, which play a critical role in maintaining axonal caliber and conduction velocity (Sakaguchi et al., 1993). Decreased NF expression can also impair axonal transport (Beitner-Johnson & Nestler, 1993), further contributing to neuronal injury and dysfunction (Nestler et al., 1996). These structural alterations in the PFC may impair synaptic efficiency and neural connectivity, thereby producing long-term deficits in emotional regulation and cognitive function. Notably, the association between NF reductions and depression-like behavior appears to be sex-specific. Jiménez-Romero et al (2020) demonstrated that prolonged withdrawal from adolescent morphine exposure significantly decreased in NF proteins in male rats, which coincided with enhanced behavioral despair. In contrast, female rats did not show comparable reductions, suggesting a distinct neurobiological response to opioid exposure. The absence of neurotoxic changes in females may reflect a neuroprotective mechanism or greater resilience during this critical developmental period. These findings underscore the importance of considering sex as a biological variable in evaluating the long-term effects of adolescent opioid exposure.

Our investigation revealed that adolescent morphine exposure was associated with a non-significant reduction in the corticosterone response to acute stressors, such as the FST, in adulthood. Although this decrease did not reach statistical significance, the large effect size suggests a potentially meaningful biological difference. This observation is consistent with previous work showing that the offspring of female rats exposed to morphine during adolescence exhibit decreased expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, along with diminished corticosterone secretion in response to stress or opioid challenge (Vassoler et al., 2018). Notably, these effects were particularly evident in males, highlighting sex-specific differences in the regulation of the HPA axis. Importantly, the alterations observed in the first-generation offspring were not attributable to differences in mu opioid receptor (Oprm1) expression within the paraventricular nucleus. However, subsequent generations displayed progressive dysregulation of Oprm1, suggesting transgenerational molecular adaptation.

More broadly, both morphine exposure and chronic stress during adolescence have been shown to exert long-lasting effects on corticosterone regulation, the primary stress hormone in rodents. Blunted corticosterone responses in adulthood may reflect an impaired ability of the HPA axis to mount or recover from acute challenges. For instance, mice subjected to chronic variable social stress during adolescence exhibit slower corticosterone recovery after acute stress in adulthood. This suggests that early-life stress may suppress the HPA axis response later in life, potentially through changes in gene expression within the PFC and other regulatory pathways (Kamens et al., 2021).

Animals exhibiting higher pain sensitivity displayed diminished anxiety-like behavior and reduced corticosterone levels. Furthermore, these animals showed increased immobility in the FST, indicating heightened depression-like behavior. Together, these observations allowed us to examine the relationships among pain sensitivity, affective behaviors, and corticosterone levels. We found significant negative correlations between PWL and measures of anxiety- and depression-like behavior, including the duration and number of open-arm entries in the EZM and immobility in the FST. This pattern indicates that reduced nociceptive sensitivity is linked to greater anxiety-like responses but diminished behavioral despair. These findings are consistent with evidence that stress and pain processing are tightly interconnected. Chronic stress can elicit both nociceptive hypersensitivity and anxiety-like behaviors through convergent neural mechanisms, particularly within the amygdala and in the regulation of the HPA axis.

Complex interactions among brain regions, neurotransmitter systems, and neuroimmune pathways mediate the neurobiological mechanisms linking nociceptive sensitivity with depression-like behavior. The ACC and amygdala are key nodes in which alterations in synaptic plasticity and extracellular matrix components (e.g. laminin β1) have been implicated in modulating both pain perception and affective behaviors, including anxiety and depression. Disruptions in these pathways may lead to nociceptive hypersensitivity and increased depression-like behavior (Chen et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Zhuo, 2016). The observed negative correlation between nociceptive thresholds and immobility in the forced swim test suggests that animals with reduced nociceptive sensitivity may display enhanced stress resilience, as indicated by reduced immobility. A significant positive correlation between PWL and serum corticosterone levels was observed, representing a key finding of this study. This relationship indicates that higher pain thresholds are correlated with increased stress-hormone levels. This observation appears paradoxical in light of the well-documented role of corticosterone in mediating stress-induced analgesia (Bodnar et al., 1980; Pinto-Ribeiro et al., 2009). This result aligns with recent evidence demonstrating a complex, bidirectional relationship between glucocorticoids and pain-processing mechanisms (Benson et al., 2019; Eller-Smith et al., 2018; Hannibal & Bishop, 2014).

Multiple underlying mechanisms may explain the observed positive correlation. One plausible mechanism involves chronic stress adaptation, in which elevated corticosterone levels reflect prolonged exposure to stress. Such sustained elevation may alter pain-processing pathways through diverse neurobiological mechanisms. Notably, prolonged glucocorticoid exposure has been demonstrated to exert antinociceptive effects by modulating neuropeptide expression in the spinal cord, including reductions in pronociceptive neuropeptides such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (Pinto-Ribeiro et al., 2009). Previous studies on stress-induced analgesia have demonstrated that acute stress elicits analgesic responses via both opioid-dependent and opioid-independent mechanisms (Bodnar et al., 1980; Gaab et al., 2017). Elevated corticosterone levels observed in animals with higher pain thresholds may reflect the activation of endogenous analgesic systems, potentially involving opioid- and non-opioid–mediated pathways (Butler & Finn, 2009; Löffler et al., 2023).

Although this study has several strengths, it is not without limitations. A primary limitation is the exclusive use of male rats, which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Given the well-established sex-specific differences in opioid sensitivity, neurodevelopmental trajectories, and stress responsiveness, future investigations should include both male and female subjects to delineate potential sex-dependent effects. Moreover, examining the interplay among nociceptive, affective, and hormonal responses across sexes may yield a more comprehensive understanding of the developmental impact of morphine. Another limitation of the present study is the exclusive focus on behavioral and hormonal outcomes without addressing the underlying molecular mechanisms. Future research would benefit from incorporating molecular analyses of key brain regions implicated in affective and pain regulation, particularly the amygdala and ACC. These regions represent critical hubs within emotional and nociceptive circuits and are especially vulnerable to drug exposure during developmental periods. Examining gene expression profiles related to stress, pain, and neuroplasticity may help elucidate the specific pathways altered by morphine exposure during adolescence. Candidate genes of particular interest include brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and c-Fos within the ACC and amygdala, as potential indicators of synaptic plasticity and emotional regulation. In addition, genes associated with glial activation and neuroinflammation, such as toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), interleukin (IL)-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, are promising targets given their established roles in opioid-induced hypersensitivity and mood dysregulation.

The present findings raise important questions regarding the long-term consequences of adolescent morphine exposure. These results suggest that even brief opioid use during this critical developmental period may produce enduring alterations in emotional behavior, pain processing, and stress regulation in adulthood. Observed changes in anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, coupled with increased pain sensitivity and attenuated HPA axis responses, indicate a reorganization of neurobiological systems that may increase vulnerability to psychiatric disorders and chronic pain later in life. These effects may arise not only from direct neurotoxic impacts on developing brain circuits but also from persistent alterations in neuroimmune and endocrine signaling. Moreover, the observed correlations among nociception, affective responses, and corticosterone levels imply shared mechanistic pathways, potentially involving glial activation, receptor desensitization, or epigenetic modifications, warranting further investigation. A comprehensive understanding of these complex interactions is essential for designing interventions to mitigate or prevent the long-term consequences of adolescent opioid exposure, particularly given the rising prevalence of opioid use among adolescents and its associated public health implications.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.MODARES.REC.1399.159).

Funding

This study was supported by the Cognitive Sciences and Technologies Council of Iran, Iran National Science Foundation (INSF), and Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Hossein Azizi and Saeed Semnanian; Methodology, and formal analysis: Nasrin Houshmandi, Hossein Azizi, and Amir Shojaei; Experiments, software, visualization and writing original draft: Nasrin Houshmandi; Review and editing: Hossein Azizi, Amir Shojaei, and Saeed Semnanian; Funding acquisition, project administration, and supervision: Saeed Semnanian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Opioids account for approximately 70% of the global burden of adverse health outcomes associated with drug use disorders (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2018). Adolescents and young adults (aged 12-25) are more susceptible to misusing prescription opioids and engaging in illicit opioid use than other age groups (National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2018). Adolescence is a critical developmental window, often marked by increased impulsivity and risk-taking behaviors (Salmanzadeh et al., 2021; Spear, 2000). This developmental stage confers heightened vulnerability to substance experimentation and increases the risk of developing substance-use disorders (Chambers et al., 2003; Salmanzadeh et al., 2020; Wagner & Anthony, 2002). Understanding the long-term consequences of opioid exposure during adolescence is essential for designing effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that morphine exposure during adolescence induces long-lasting alterations in pain modulation and opioid responsiveness. Specifically, adolescent morphine administration accelerated the development of tolerance to its antinociceptive effects and increased the excitability of neurons in the lateral paragigantocellularis (LPGi) region (Salmanzadeh et al., 2017; Samanzadeh et al., 2018). Furthermore, rats exposed to morphine during adolescence exhibited heightened pain sensitivity in adulthood, with significantly elevated pain scores across all phases of the formalin test compared to controls (Ghasemi et al., 2019). Recently, our findings revealed that adolescent morphine exposure exacerbated both allodynia and hyperalgesia in adulthood under both baseline and neuropathic pain conditions (Alami et al., 2025). These findings collectively suggest that opioid exposure during sensitive periods of neurodevelopment can induce persistent changes in both pain sensitivity and opioid efficacy.

Epidemiological studies have shown a strong relationship between opioid use disorders and the later development of mood disorders (Grant et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 2003; Kessler et al., 2005; Regier et al., 1990). We previously observed that chronic morphine exposure during adolescence reduces anxiety-like behavior in adulthood, as assessed using the open field and elevated plus maze (Khani et al., 2022). In the present study, we utilized the elevated zero maze (EZM), which offers methodological advantages over the traditional elevated plus maze by removing the ambiguous central zone and allowing continuous exploration, to more accurately assess anxiety-related behavior.

Anxiety and emotional regulation are closely associated with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs the stress response via glucocorticoid secretion. The endogenous opioid system modulates HPA axis activity through both inhibitory and excitatory pathways (Odio & Brodish, 1990). Dysregulation of the HPA axis has been implicated in mood and anxiety disorders (Holsboer & Ising, 2010; Kammerer et al., 2006). Pharmacological studies have shown that mu-opioid receptor agonists, such as morphine, reduce anxiety, whereas antagonists tend to produce anxiogenic effects (Asakawa et al., 1998; Kõks et al., 1998; Tsuda et al., 1996; Zarrindast et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 1996). Notably, prior research suggests that adolescent morphine exposure may induce long-lasting, sex specific alterations in HPA axis function, even across generations (Vassoler et al., 2014; Vassoler et al., 2018).

To address existing gaps in the literature, the present study is the first to evaluate plasma corticosterone levels in adulthood following adolescent morphine exposure. Importantly, this study uniquely assessed behavioral profiles, including pain sensitivity, anxiety-like behavior, depression-like behavior, and corticosterone levels within the same animals. This was integrated within the subject design, enabling the investigation of potential associations between behavioral and neuroendocrine outcomes, providing a more integrated understanding of the long-term effects of adolescent opioid exposure on emotional behavior, stress regulation, and nociceptive processing. Identifying multidimensional behavioral patterns associated with adolescent morphine exposure remains challenging. While individual behavioral tests provide limited insight, multivariate approaches, such as principal component analysis (PCA), allow detection of integrated behavioral changes that persist into adulthood. This study also investigated whether morphine administration during adolescence produces distinguishable adult behavioral signatures, which could improve understanding of the long-term effects of morphine exposure on behavioral profile.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats were obtained on postnatal day (PND) 23 from the Razi Institute (Tehran, Iran) and housed in groups of four under controlled conditions (12-hour light/dark cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water). The animals were allowed to acclimate for one week before the experimental procedures. All protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences at Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran, and conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Experimental procedure

To reduce stress, rats were gently handled daily during the acclimation period.

Beginning on PND 31, adolescent rats received subcutaneous (s.c.) injections of morphine sulfate (Temad, Tehran, Iran) twice daily (08:00 and 20:00) for 10 consecutive days. Morphine was administered according to an escalating dose regimen of 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 17.5, 20, 22.5, and 25 mg/kg. For each injection, the appropriate dose was freshly prepared by dissolving morphine in 2 mL of sterile normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride [NaCl]) immediately prior to administration. Age-matched control animals were administered equivalent volumes of saline using the same injection schedule. After the final injection, all animals remained drug-free for a 20-day washout period. Behavioral assessments were conducted between PND 60 and 65 (Figure 1).

Behavioral experiments

Open field test (OFT)

The OFT was used to evaluate anxiety-related behaviors. The testing apparatus comprised a black Plexiglass square arena (measuring 60×60×60 cm) with its floor divided into 16 squares by virtual lines, delineating the central and peripheral areas. The rats were placed in the central part of the arena and given five minutes to explore their surroundings freely. The rat’s movements were observed and documented using a video-tracking system (EthoVision software,version 9; Noldus Information Technology, Netherlands). Locomotor activity was assessed by recording the distance travelled over 5 minutes. Additionally, the duration the animal spent in the center of the open field was measured to assess anxiety-like behaviors (Walsh & Cummins, 1976). After each test, the arena was cleaned with 70% ethanol.

EZM test

The EZM consisted of a circular platform made of black Perspex. The platform had a diameter of 105 cm and a width of 10 cm. It was elevated 65 cm above the ground and divided into four quadrants. Each rat was initially placed in the central region of the enclosed square during the 10-minute testing period. After each testing session, the maze is sanitized with 70% ethanol and left to air dry. The animal’s movements within the maze were recorded using an overhead camera and subsequently analyzed with a tracking system (EthoVision XT, version 9; Noldus Information Technology, Netherlands). The key behavioral parameters included the number of entries into each arm and the duration of time spent in each arm (Shepherd et al., 1994).

Von-Frey (VF) test

Mechanical pain sensitivity was evaluated using VF filaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA) applied to the plantar surface of the hind paw, according to the up–down method outlined by Chaplan et al. (1994). Animals were placed individually in transparent acrylic enclosures on a 30 cm-high elevated wire-mesh platform (11×12×20 cm) to allow access to the paw. Prior to testing, the rats were habituated to the apparatus for 15 minutes. A collection of 10 VF filaments, with stiffness values increasing logarithmically (0.4, 0.6, 1, 1.4, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 26 g), was employed. During the test, each filament was applied perpendicularly to the mid-plantar region of both paws until it bent, and held for 2–5 s. Each filament was presented five times, and the withdrawal responses were recorded to determine mechanical sensitivity.

Hargreaves test

The latency of paw withdrawal in response to thermal stimuli was measured using radiant heat with a Hargreaves apparatus (IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, CA, USA). Unrestrained animals were placed in Plexiglass containers (11×12×20 cm) and allowed to acclimate for 15 minutes. Subsequently, a radiant heat source was applied to the plantar surface of both hind paws. The testing device was set to approximately 55% of its maximum power. Thermal response latencies were documented across three distinct trials, each conducted at a 5-minute interval. The mean of these three measurements was determined as the paw withdrawal latency (PWL). A maximum cut-off duration of 20 s was implemented to avert potential tissue damage (Hargreaves et al., 1988).

Forced swimming test (FST)

The FST was a two-day testing process. During the pre-test session, rats were individually submerged in a glass cylinder (95 cm high and 15.5 cm in diameter) filled with 30 cm of water maintained at 23-24 °C for 15 minutes. The next day, these rats were subjected to a 5-minute test session. The experiment’s testing section was monitored and assessed by an unbiased observer using a computer-based event recording system. Following the FST, rats were towel-dried and returned to their home cages, which were maintained for approximately 20 minutes to aid recovery (Porsolt et al., 1977).

Blood collection and corticosterone measurement

Thirty minutes following the completion of the 6-minute FST, the rats were decapitated, and trunk blood was collected into sterile Eppendorf tubes (Connor et al., 1997). Samples were immediately placed on ice, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C, and the resulting serum was stored at −80 °C until analysis. Serum corticosterone concentrations were determined using a commercially available ELISA kit (Cat. No: CSB-E05112r; Cusabio, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 µL of serum was added to 100 µL of enzyme conjugate per well, and the plate was incubated for 30 minutes at 37 °C. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer. The assay demonstrated good precision, with intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation below 8% and 10%, respectively. Corticosterone levels were calculated using a standard curve constructed from serial dilutions ranging from 3.12 to 200 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 1.56 ng/mL.

Behavioral PCA

Adult rodents previously treated with morphine or saline during adolescence were evaluated across multiple behavioral assays, including the OFT, EZM, VF, Hargreaves, and FST. Eight behavioral measures were standardized using Z-scores and analyzed using PCA to reduce dimensionality and identify principal components capturing maximal variance. PCA scores and loadings were visualized to examine treatment-specific clustering and the contribution of each behavioral measure to the principal components (Python 3.13.5, Anaconda Distribution, Anaconda Inc).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software, version 7. Data are expressed as Mean±SEM, with a P<0.05 indicating statistical significance. Data distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test. For datasets exhibiting normal distributions, an unpaired student’s t-test was employed, whereas the Mann–Whitney U test was utilized for datasets not conforming to this distribution.

Results

Adolescent morphine exposure effects on anxiety-like behavior in adulthood

From PND 31 to 40, adolescent rats were subjected to chronic morphine exposure for 10 consecutive days. To assess anxiety-like behavior, behavioral testing was conducted on PND 60 and 61 using the OFT and EZM (Figure 1).

Treatment and behavioral testing

Rats were administered either saline or morphine during adolescence (PNDs 31–40). Between PNDs 60 and 65, a series of behavioral tests were conducted to assess long-term effects. Anxiety-like behavior was evaluated using the OFT and EZM, while pain sensitivity was assessed with the VF and Hargreaves tests. Depression-like behavior was examined using the FST, followed by blood collection for corticosterone level measurement.

In the OFT, morphine-exposed rats spent significantly more time in the center of the arena than saline-treated controls (t=2.982, P=0.0080; Figure 2A), suggesting reduced anxiety-like behavior. However, no significant difference was observed in the total distance travelled between the two groups (t=1.993, P=0.0616; Figure 2B), indicating that locomotor activity was not affected. Anxiety-like behavior was further evaluated using the EZM test. Rats exposed to morphine during adolescence spent more time in the open arms (t=3.207, P=0.0076; Figure 2C) and made significantly more entries into the open arms (Mann-Whitney U=20, P=0.0221; Figure 2D) compared to the saline group, further supporting an anxiolytic-like effect of adolescent morphine exposure.

Adolescent morphine exposure effects on pain thresholds in adulthood

Next, we assessed mechanical allodynia, defined as abnormal sensitivity to non-noxious mechanical stimuli, and thermal hyperalgesia, characterized by an intensified response to noxious thermal stimuli, on PNDs 62 and 63 (Figure 1). Mechanical allodynia was evaluated using the VF filament test. Adolescent rats exposed to morphine exhibited a significantly reduced threshold for tactile sensitivity in both hind paws compared to saline-treated controls (right paw: Mann-Whitney U=0, P<0.0001; left paw: Mann-Whitney U=3.5, P=0.0001; Figure 3A). Thermal nociception was assessed using the Hargreaves test to determine the effects of morphine exposure during adolescence. Morphine-treated rats demonstrated significantly decreased paw withdrawal latencies in both hind paws relative to the saline group, indicating heightened thermal sensitivity (right paw: Mann-Whitney U=0, P<0.0001; left paw: Mann-Whitney U=0, P<0.0001; Figure 3B).

Adolescent morphine exposure effects on depression-like behavior in adulthood

Depression-like behavior was evaluated using the FST on PND 65 (Figure 1). Animals exposed to morphine during adolescence exhibited a significant increase in total immobility time compared to saline-treated controls (t=2.528, P=0.0210; Figure 4A), indicating enhanced behavioral despair. In contrast, no significant difference was observed between the groups in latency to first immobility (Mann–Whitney U=35, P=0.2761; Figure 4B).

Adolescent morphine exposure effects on serum corticosterone level in adulthood

Following the FST, we measured serum corticosterone levels to assess the physiological stress response. Our analysis revealed a reduction in corticosterone concentrations in adolescent rats treated with morphine compared to those treated with saline. However, this difference was not statistically significant (t=2.282, P=0.0663; Figure 5), but the magnitude of the difference showed a large effect size (Cohen’s d=1.44), suggesting that chronic morphine exposure during adolescence may markedly attenuate HPA axis responsiveness in adulthood.

Correlation between nociceptive sensitivity and behavioral and hormonal stress responses

To investigate the relationship between nociceptive sensitivity and stress-related phenotypes, we conducted correlation analyses between PWL and multiple behavioral and hormonal stress markers. Specifically, we examined the associations between PWL and the following variables: The number of entries into the open arms of the EZM, the duration spent in the open arms of the EZM, serum corticosterone concentrations, and immobility time in the FST. These analyses aimed to determine whether altered pain sensitivity is associated with anxiety-like behavior, HPA axis regulation, and behavioral despair.

PWL demonstrated a significant negative correlation with the number of entries into the open arms of the EZM (r=-0.5513, P=0.0117; Figure 6A), and a significant negative correlation with the duration spent in the open arms (r=-0.4936, P=0.0270; Figure 6B), suggesting that reduced nociceptive sensitivity may be associated with increased anxiety-like behavior. In addition, PWL was significantly negatively correlated with immobility time in the FST (r=–0.4582, P=0.0422; Figure 6C), indicating a potential link between lower pain sensitivity and reduced behavioral despair. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation was observed between PWL and serum corticosterone concentrations (r=0.7047, P=0.0229; Figure 6D), highlighting a possible relationship between pain sensitivity and stress hormone levels.

Treatment-specific behavioral profiles revealed by PCA

PCA showed that the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) explained 43.7% and 17.3% of the total variance, respectively (Figure 7C). Morphine-treated animals clustered distinctly from saline-treated controls along PC1 (Figure 7A), demonstrating systematic behavioral differences induced by adolescent morphine exposure. Loading analysis indicated that OFTT (T: Travelled distance), EZMTO (TO: Time spent in the open arm), and FSTL (L: latency to first immobilization) contributed most strongly to PC1, whereas Hargreaves and VF measurements loaded predominantly on PC2 (Figure 7B). These results suggest that adolescent morphine treatment produces separable multidimensional behavioral profiles in adulthood, affecting both OFT/EZM-related parameters and nociceptive measures. Since the number of animals (20 subjects) relative to the number of variables (8 behavioral measures) did not reach the ideal 5:1 ratio, the PCA results were reported as an exploratory analysis and should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that exposure to morphine during adolescence produces enduring behavioral and neuroendocrine disturbances in adulthood. Compared to saline-treated rats, morphine-exposed animals exhibited reduced anxiety-like behavior, heightened pain sensitivity (manifested as both hyperalgesia and allodynia), and increased depression-like responses. The PCA results also demonstrate that adolescent morphine exposure produces a distinct and lasting behavioral profile in adulthood, clearly separating treated animals from saline controls. These findings indicate that morphine influences multiple behavioral domains in a coordinated manner, underscoring the utility of multivariate approaches, such as PCA, for capturing complex treatment-specific patterns that may otherwise go undetected in univariate analyses.

Adolescence represents a critical developmental window during which the opioid system is still maturing, as receptor expression gradually reaches functionally adequate levels (Carretero et al., 2004; Gazyakan et al., 2000; Kivell et al., 2004). Chronic morphine exposure during this period can induce persistent alterations in both mu and kappa opioid receptor systems, which play essential roles in regulating affective states (Byrnes, 2008; Mague et al., 2003). The emotional and anxiety-like behavioral alterations observed following adolescent morphine exposure may be partly attributed to the incomplete development of top-down regulatory systems responsible for behavioral control that are more fully established in adulthood (Casey & Caudle, 2013). These behavioral modifications may be driven by disrupted prefrontal cortex (PFC)–amygdala circuitry (Figueroa et al., 2021), alterations in mesolimbic dopamine signaling, including D1 receptor and tyrosine hydroxylase expression (Bolaños et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2022), and dysregulation of activity-dependent genes involved in synaptic plasticity (e.g. c-Fos and ΔFosB) (Figueroa et al., 2021; Yazdanfar et al., 2021). Our findings are consistent with previous research from our laboratory, which demonstrated similar anxiety-like behavioral changes using the open field and elevated plus maze following adolescent morphine exposure (Khani et al., 2022).

Interestingly, evidence suggests the potential transgenerational effects of adolescent morphine exposure. For example, female rats exposed to morphine during adolescence produced offspring that exhibited reduced anxiety-like behaviors in adulthood, possibly influenced by hormonal cycles and transgenerational mechanisms (Vassoler & Byrnes, 2021). Comparable findings have been reported for other psychostimulants. Adolescent exposure to cocaine (Daws et al., 2011) and methamphetamine (Buck et al., 2017) has been associated with reduced anxiety-like behavior in adulthood, whereas exposure to THC (tetrahydrocannabinol: Cannabinoid receptor agonist) is associated with increased anxiety-like behaviors in adulthood (Higuera-Matas et al., 2009; Llorente-Berzal et al., 2013; Renard et al., 2017). These divergent effects highlight the complexity of drug exposure during adolescence. Notably, Zhu et al. (2016) found that adolescent cocaine administration could also lead to anxiogenic responses in adulthood, while other studies reported no significant long-term effects (Bortolato et al., 2014; Rubino et al., 2008; Sanchez et al., 2016). Such discrepancies underscore the influence of experimental variables, including strain differences, sex, dosage regimens, developmental timing, and duration of drug exposure, all of which can critically shape long-term behavioral outcomes (Azadi et al., 2021).

Consistent with our findings, previous investigations on adolescent morphine exposure have reported no significant differences in total distance traveled or overall activity levels when comparing treated and control animals. This suggests that the observed behavioral changes were specific to anxiety-like responses rather than general locomotor activity (Khani et al., 2022; Vassoler & Byrnes, 2021). The mechanisms underlying these long-lasting alterations appear to involve brain regions critically implicated in emotional regulation, particularly the amygdala and PFC, both of which are susceptible to drug exposure during adolescence (Akwa et al., 1999; Kenwood et al., 2022). Evidence from studies on other psychostimulants supports this view. For instance, adolescent cocaine use has been shown to induce enduring emotional effects by transiently altering gene expression patterns related to synaptic development within the amygdala (Daws et al., 2011). Similarly, adolescent amphetamine exposure disrupts inhibitory signaling in the PFC by interfering with dopamine–GABA interactions (Kang et al., 2016; Paul et al., 2016), and subsequently enhances monoaminergic activity in adulthood (Labonte et al., 2012).

The dopaminergic system, which undergoes heightened activity during adolescence, is particularly vulnerable to drug-induced modifications (Wahlstrom et al., 2010). In parallel, prolonged opioid exposure has been reported to reduce levels of cytoskeletal proteins, such as neurofilaments (NFs), within the PFC (Beitner-Johnson et al., 1992; Boronat et al., 1998; Garcí-Sevilla et al., 1997). Such reductions are thought to contribute to neurotoxicity and cortical degeneration (Jiménez-Romero et al., 2020; Nestler et al., 1996). These structural vulnerabilities in key cortical and limbic circuits may underlie the persistent emotional and behavioral disturbances observed following adolescent morphine exposure.

We observed reduced pain thresholds in adulthood following adolescent morphine exposure. This result is consistent with previous findings from our laboratory, which similarly reported long-lasting alterations in nociceptive processing (Alami et al., 2024; Ghasemi et al., 2019; Pachenari et al., 2018). Our findings align with broader evidence indicating that morphine exposure during early developmental stages produces enduring changes in pain sensitivity. For example, exposure during infancy has been shown to reduce both thermal and mechanical pain thresholds and to enhance formalin-evoked nociceptive behaviors in later life (Nunes et al., 2017; Rozisky et al., 2012). These results suggest that opioid exposure during critical developmental periods may predispose individuals to long-lasting hypersensitivity.

The mechanisms underlying these effects may involve neuroimmune processes, particularly microglial activation and inflammatory signaling (Ho et al., 2020). The toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) has been implicated explicitly in morphine-induced allodynia (Ellis et al., 2016; Green-Fulgham et al., 2019). Notably, inhibiting microglial activation during adolescence has been shown to mitigate hypersensitivity, highlighting this pathway as a potential therapeutic target (Alami et al., 2025).

Persistent nociceptive alterations following adolescent morphine exposure also appear to involve changes in brain regions that regulate pain. Modifications in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG) and LPGi nuclei have been linked to disrupted endogenous opioid signaling and altered neuronal activity (Alami et al., 2024; Salmanzadeh et al., 2018). In addition, our laboratory previously demonstrated that adolescent morphine exposure induces long-lasting alterations in the locus coeruleus, a key brain region involved in pain modulation, and enhances its excitability in subsequent generations (Pachenari et al., 2019).

Our findings of increased pain sensitivity, together with reduced anxiety-like behavior, raise important questions about whether these alterations are also accompanied by changes in depression-like states. Pain processing and emotional regulation share overlapping neural substrates, including the PFC, amygdala, and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), as well as common neuroimmune mechanisms such as microglial activation (Duan et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025). Given these shared pathways, it is plausible that adolescent morphine exposure induces parallel changes across nociceptive and affective domains. Therefore, we evaluated the impact of adolescent morphine exposure on depression-like responses.

Depression-like behavior was assessed using the FST, in which morphine-exposed animals exhibited increased immobility, a well-established marker of behavioral despair. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have reported that adolescent morphine exposure in both mice and rats leads to the emergence of depression-like behavior later in life (Jiménez-Romero et al., 2020; Lutz et al., 2013). These animal models have provided important insights, although most have relied on specific strains and dosing regimens that differ from the approach used in our study. By employing a different rat strain and varying morphine dosages, and durations of exposure, our results expand on the existing literature and highlight the robustness of this behavioral outcome.

Prolonged morphine exposure during adolescence disrupts the normal development of neural circuits involved in emotional regulation, particularly within the PFC. This disruption is associated with neurotoxic effects, including reductions in NF proteins, which play a critical role in maintaining axonal caliber and conduction velocity (Sakaguchi et al., 1993). Decreased NF expression can also impair axonal transport (Beitner-Johnson & Nestler, 1993), further contributing to neuronal injury and dysfunction (Nestler et al., 1996). These structural alterations in the PFC may impair synaptic efficiency and neural connectivity, thereby producing long-term deficits in emotional regulation and cognitive function. Notably, the association between NF reductions and depression-like behavior appears to be sex-specific. Jiménez-Romero et al (2020) demonstrated that prolonged withdrawal from adolescent morphine exposure significantly decreased in NF proteins in male rats, which coincided with enhanced behavioral despair. In contrast, female rats did not show comparable reductions, suggesting a distinct neurobiological response to opioid exposure. The absence of neurotoxic changes in females may reflect a neuroprotective mechanism or greater resilience during this critical developmental period. These findings underscore the importance of considering sex as a biological variable in evaluating the long-term effects of adolescent opioid exposure.

Our investigation revealed that adolescent morphine exposure was associated with a non-significant reduction in the corticosterone response to acute stressors, such as the FST, in adulthood. Although this decrease did not reach statistical significance, the large effect size suggests a potentially meaningful biological difference. This observation is consistent with previous work showing that the offspring of female rats exposed to morphine during adolescence exhibit decreased expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, along with diminished corticosterone secretion in response to stress or opioid challenge (Vassoler et al., 2018). Notably, these effects were particularly evident in males, highlighting sex-specific differences in the regulation of the HPA axis. Importantly, the alterations observed in the first-generation offspring were not attributable to differences in mu opioid receptor (Oprm1) expression within the paraventricular nucleus. However, subsequent generations displayed progressive dysregulation of Oprm1, suggesting transgenerational molecular adaptation.

More broadly, both morphine exposure and chronic stress during adolescence have been shown to exert long-lasting effects on corticosterone regulation, the primary stress hormone in rodents. Blunted corticosterone responses in adulthood may reflect an impaired ability of the HPA axis to mount or recover from acute challenges. For instance, mice subjected to chronic variable social stress during adolescence exhibit slower corticosterone recovery after acute stress in adulthood. This suggests that early-life stress may suppress the HPA axis response later in life, potentially through changes in gene expression within the PFC and other regulatory pathways (Kamens et al., 2021).

Animals exhibiting higher pain sensitivity displayed diminished anxiety-like behavior and reduced corticosterone levels. Furthermore, these animals showed increased immobility in the FST, indicating heightened depression-like behavior. Together, these observations allowed us to examine the relationships among pain sensitivity, affective behaviors, and corticosterone levels. We found significant negative correlations between PWL and measures of anxiety- and depression-like behavior, including the duration and number of open-arm entries in the EZM and immobility in the FST. This pattern indicates that reduced nociceptive sensitivity is linked to greater anxiety-like responses but diminished behavioral despair. These findings are consistent with evidence that stress and pain processing are tightly interconnected. Chronic stress can elicit both nociceptive hypersensitivity and anxiety-like behaviors through convergent neural mechanisms, particularly within the amygdala and in the regulation of the HPA axis.

Complex interactions among brain regions, neurotransmitter systems, and neuroimmune pathways mediate the neurobiological mechanisms linking nociceptive sensitivity with depression-like behavior. The ACC and amygdala are key nodes in which alterations in synaptic plasticity and extracellular matrix components (e.g. laminin β1) have been implicated in modulating both pain perception and affective behaviors, including anxiety and depression. Disruptions in these pathways may lead to nociceptive hypersensitivity and increased depression-like behavior (Chen et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; Zhuo, 2016). The observed negative correlation between nociceptive thresholds and immobility in the forced swim test suggests that animals with reduced nociceptive sensitivity may display enhanced stress resilience, as indicated by reduced immobility. A significant positive correlation between PWL and serum corticosterone levels was observed, representing a key finding of this study. This relationship indicates that higher pain thresholds are correlated with increased stress-hormone levels. This observation appears paradoxical in light of the well-documented role of corticosterone in mediating stress-induced analgesia (Bodnar et al., 1980; Pinto-Ribeiro et al., 2009). This result aligns with recent evidence demonstrating a complex, bidirectional relationship between glucocorticoids and pain-processing mechanisms (Benson et al., 2019; Eller-Smith et al., 2018; Hannibal & Bishop, 2014).

Multiple underlying mechanisms may explain the observed positive correlation. One plausible mechanism involves chronic stress adaptation, in which elevated corticosterone levels reflect prolonged exposure to stress. Such sustained elevation may alter pain-processing pathways through diverse neurobiological mechanisms. Notably, prolonged glucocorticoid exposure has been demonstrated to exert antinociceptive effects by modulating neuropeptide expression in the spinal cord, including reductions in pronociceptive neuropeptides such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (Pinto-Ribeiro et al., 2009). Previous studies on stress-induced analgesia have demonstrated that acute stress elicits analgesic responses via both opioid-dependent and opioid-independent mechanisms (Bodnar et al., 1980; Gaab et al., 2017). Elevated corticosterone levels observed in animals with higher pain thresholds may reflect the activation of endogenous analgesic systems, potentially involving opioid- and non-opioid–mediated pathways (Butler & Finn, 2009; Löffler et al., 2023).

Although this study has several strengths, it is not without limitations. A primary limitation is the exclusive use of male rats, which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Given the well-established sex-specific differences in opioid sensitivity, neurodevelopmental trajectories, and stress responsiveness, future investigations should include both male and female subjects to delineate potential sex-dependent effects. Moreover, examining the interplay among nociceptive, affective, and hormonal responses across sexes may yield a more comprehensive understanding of the developmental impact of morphine. Another limitation of the present study is the exclusive focus on behavioral and hormonal outcomes without addressing the underlying molecular mechanisms. Future research would benefit from incorporating molecular analyses of key brain regions implicated in affective and pain regulation, particularly the amygdala and ACC. These regions represent critical hubs within emotional and nociceptive circuits and are especially vulnerable to drug exposure during developmental periods. Examining gene expression profiles related to stress, pain, and neuroplasticity may help elucidate the specific pathways altered by morphine exposure during adolescence. Candidate genes of particular interest include brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and c-Fos within the ACC and amygdala, as potential indicators of synaptic plasticity and emotional regulation. In addition, genes associated with glial activation and neuroinflammation, such as toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), interleukin (IL)-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, are promising targets given their established roles in opioid-induced hypersensitivity and mood dysregulation.

The present findings raise important questions regarding the long-term consequences of adolescent morphine exposure. These results suggest that even brief opioid use during this critical developmental period may produce enduring alterations in emotional behavior, pain processing, and stress regulation in adulthood. Observed changes in anxiety- and depression-like behaviors, coupled with increased pain sensitivity and attenuated HPA axis responses, indicate a reorganization of neurobiological systems that may increase vulnerability to psychiatric disorders and chronic pain later in life. These effects may arise not only from direct neurotoxic impacts on developing brain circuits but also from persistent alterations in neuroimmune and endocrine signaling. Moreover, the observed correlations among nociception, affective responses, and corticosterone levels imply shared mechanistic pathways, potentially involving glial activation, receptor desensitization, or epigenetic modifications, warranting further investigation. A comprehensive understanding of these complex interactions is essential for designing interventions to mitigate or prevent the long-term consequences of adolescent opioid exposure, particularly given the rising prevalence of opioid use among adolescents and its associated public health implications.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.MODARES.REC.1399.159).

Funding

This study was supported by the Cognitive Sciences and Technologies Council of Iran, Iran National Science Foundation (INSF), and Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Hossein Azizi and Saeed Semnanian; Methodology, and formal analysis: Nasrin Houshmandi, Hossein Azizi, and Amir Shojaei; Experiments, software, visualization and writing original draft: Nasrin Houshmandi; Review and editing: Hossein Azizi, Amir Shojaei, and Saeed Semnanian; Funding acquisition, project administration, and supervision: Saeed Semnanian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Akwa, Y., Purdy, R. H., Koob, G. F., & Britton, K. T. (1999). The amygdala mediates the anxiolytic-like effect of the neurosteroid allopregnanolone in rat. Behavioural Brain Research, 106(1-2), 119-125. [DOI:10.1016/S0166-4328(99)00101-1] [PMID]

Alami, K., Fathollahi, Y., Hashemizadeh, S., Mosleh, M., Semnanian, S., & Mousavi, S. Y., et al. (2025). Microglia-dependent peripheral neuropathic pain in adulthood following adolescent exposure to morphine in male rats. Neuropharmacology, 263, 110211. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2024.110211] [PMID]

Alami, K., Ghasemi, E., Semnanian, S., & Azizi, H. (2024). Adolescent morphine exposure changes the endogenous vlPAG opioid response to inflammatory pain in rats. Developmental Psychobiology, 66(1), e22447. [DOI:10.1002/dev.22447] [PMID]

Asakawa, A., Inui, A., Momose, K., Ueno, N., Fujino, M. A., & Kasuga, M. (1998). Endomorphins have orexigenic and anxiolytic activities in mice. Neuroreport, 9(10), 2265-2267. [DOI:10.1097/00001756-199807130-00022] [PMID]

Azadi, M., Zare, M., Pachenari, N., Shojaei, A., Semnanian, S., & Azizi, H. (2021). Sex-specific transgenerational effects of adolescent morphine exposure on short-term memory and anxiety behavior: male linage. Neuroscience Letters, 761, 136111. [DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2021.136111] [PMID]