Volume 16, Issue 5 (September & October 2025)

BCN 2025, 16(5): 857-868 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Niknamfar S, Alaedini K, Mokri A, Nazar E, Rafaiee R, Seyedhosseini Tamijani S M, et al . tDCS Targeting the DLPFC for Reducing Cigarette Craving and Risky Decision Making. BCN 2025; 16 (5) :857-868

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3259-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3259-en.html

Saba Niknamfar1

, Kamaledin Alaedini2

, Kamaledin Alaedini2

, Azarakhsh Mokri3

, Azarakhsh Mokri3

, Eisa Nazar2

, Eisa Nazar2

, Raheleh Rafaiee1

, Raheleh Rafaiee1

, Seyedeh Masoumeh Seyedhosseini Tamijani1

, Seyedeh Masoumeh Seyedhosseini Tamijani1

, Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini4

, Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini4

, Hamed Ghazvini *5

, Hamed Ghazvini *5

, Kamaledin Alaedini2

, Kamaledin Alaedini2

, Azarakhsh Mokri3

, Azarakhsh Mokri3

, Eisa Nazar2

, Eisa Nazar2

, Raheleh Rafaiee1

, Raheleh Rafaiee1

, Seyedeh Masoumeh Seyedhosseini Tamijani1

, Seyedeh Masoumeh Seyedhosseini Tamijani1

, Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini4

, Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini4

, Hamed Ghazvini *5

, Hamed Ghazvini *5

1- Department of Neuroscience, Faculty of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

2- Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Addiction Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

3- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Psychiatry, Psychosomatic Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Sari Imam Khomeini Hospital, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

5- Department of Neuroscience, Faculty of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. & Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Addiction Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

2- Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Addiction Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

3- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Psychiatry, Psychosomatic Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Sari Imam Khomeini Hospital, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

5- Department of Neuroscience, Faculty of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. & Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Addiction Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

Keywords: Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), Risky decision-making behavior, Brain wave pattern, Nicotine, Craving

Full-Text [PDF 1725 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

Introduction

Aicotine is the main psychoactive component of cigarette smoke and plays a major role in the global burden of disease. Cigarette smoking, a prevalent form of tobacco use, is a significant public health risk, and it is projected that the number of smokers will increase to 1.7 billion by 202 (Conti & Baldacchino, 2021; WHO, 2020). It is estimated that by 2030, the number of deaths caused by smoking will reach 8 million annually. Additionally, smokers often exhibit behaviors such as risky decision-making (Kekic et al., 2016). Currently, many approaches are used to prevent and manage tobacco addiction. Despite numerous available interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and pharmaceutical treatments, smoking relapse remains a major challenge (Cahill et al., 2013; Stead et al., 2016). Thus, novel strategies such as brain stimulation have been proposed to reduce tobacco cravings and support smoking cessation. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a widely used non-invasive technique for modulating brain function, particularly in individuals with central nervous system (CNS) disorders (Shourmasti et al., 2023). Numerous studies have verified that tDCS can modulate excitability in both superficial and deep brain structures. During tDCS, anodal stimulation increases cortical excitability through neural depolarization, whereas cathodal stimulation reduces it via hyperpolarization (Barr et al., 2008; Garavan & Hester, 2007). Since alterations in the activity of prefrontal regions, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), are associated with drug craving, studies suggest that anodal tDCS may enhance DLPFC activity and thereby reduce craving (Fregni et al., 2008; Huhn et al., 2019). Loss of control over drug-seeking is a well-recognized feature of drug addiction, which is defined as a compulsive drive to seek drugs for acute rewards despite the risk of aversive consequences.

In this manner, dysfunctions within prefrontal cortical circuits, the DLPFC, contribute to impaired decision-making and cognitive evaluation of consequences, which play a key role in compulsive drug-seeking behavior. In addition, several human studies emphasized that drug addiction leads to significant behavioral impairments in tasks related to making risky decisions (Balconi et al., 2014; Gorini et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013). From this perspective, evidence suggests that tDCS applied to frontal regions such as the DLPFC can influence risk-taking behavior. For instance, Gorini et al. (2014) demonstrated that anodal stimulation of the DLPFC modulated risky choices in abstinent, cocaine-dependent individuals. Moreover, to date, few studies have investigated the effects of non-invasive brain stimulation on electroencephalography (EEG) frequency power changes in cigarette smokers. In a study, Pripfl et al. (2014) applied repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to the left DLPFC and reduced nicotine craving and found decreased EEG delta power in cigarette smokers. It appears that a decrease in delta power has been associated with increased activity of the dopaminergic mesolimbic system. Nevertheless, from a neuropsychological perspective, risk-taking and addictive behaviors share several features that influence brain electrical activity. Taken together, this study aims to evaluate and compare the effects of the left and right-sided tDCS over the DLPFC on performance in two risk-taking tasks and EEG frequency power changes in nicotine smokers and control participants.

Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of tDCS on the DLPFC in reducing craving, risky decision-making, and altering EEG power spectra in cigarette smokers. We hypothesize that tDCS can alter EEG frequency power in the DLPFC, thereby decreasing craving and risky decision-making, and ultimately leading to reduced cigarette consumption among smokers.

Specific objectives

To assess the effect of tDCS on nicotine craving in cigarette smokers using the tobacco craving questionnaire (TCQ).

To compare the differential effects of left- versus right-sided DLPFC stimulation on craving intensity.

To examine the effects of left- and right-sided tDCS on risky decision-making behavior using the Iowa gambling task (IGT) and the balloon analogue risk task (BART).

To analyze shifts in the power spectra of the EEG (alpha, beta, theta, delta, and gamma bands) after stimulation of the left and right DLPFC, comparing relative power and dominant brainwave profiles after tDCS in both conditions.

Trial design

This randomized clinical trial includes three parallel arms: An intervention group, a control group, and a sham group. The study aims to evaluate the effects of electrical stimulation on the DLPFC on risky decision-making and brain wave patterns, and craving induction in cigarette smokers. Participants will be randomly assigned to one of the three groups to ensure balanced allocation across study arms. Specific outcome measures will include decision-making tasks and EEG recordings to assess brain wave patterns associated with craving and risk-related behavior. This structured approach enables a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of electrical stimulation in enhancing decision-making compared to sham treatment.

Materials and Methods

Study setting

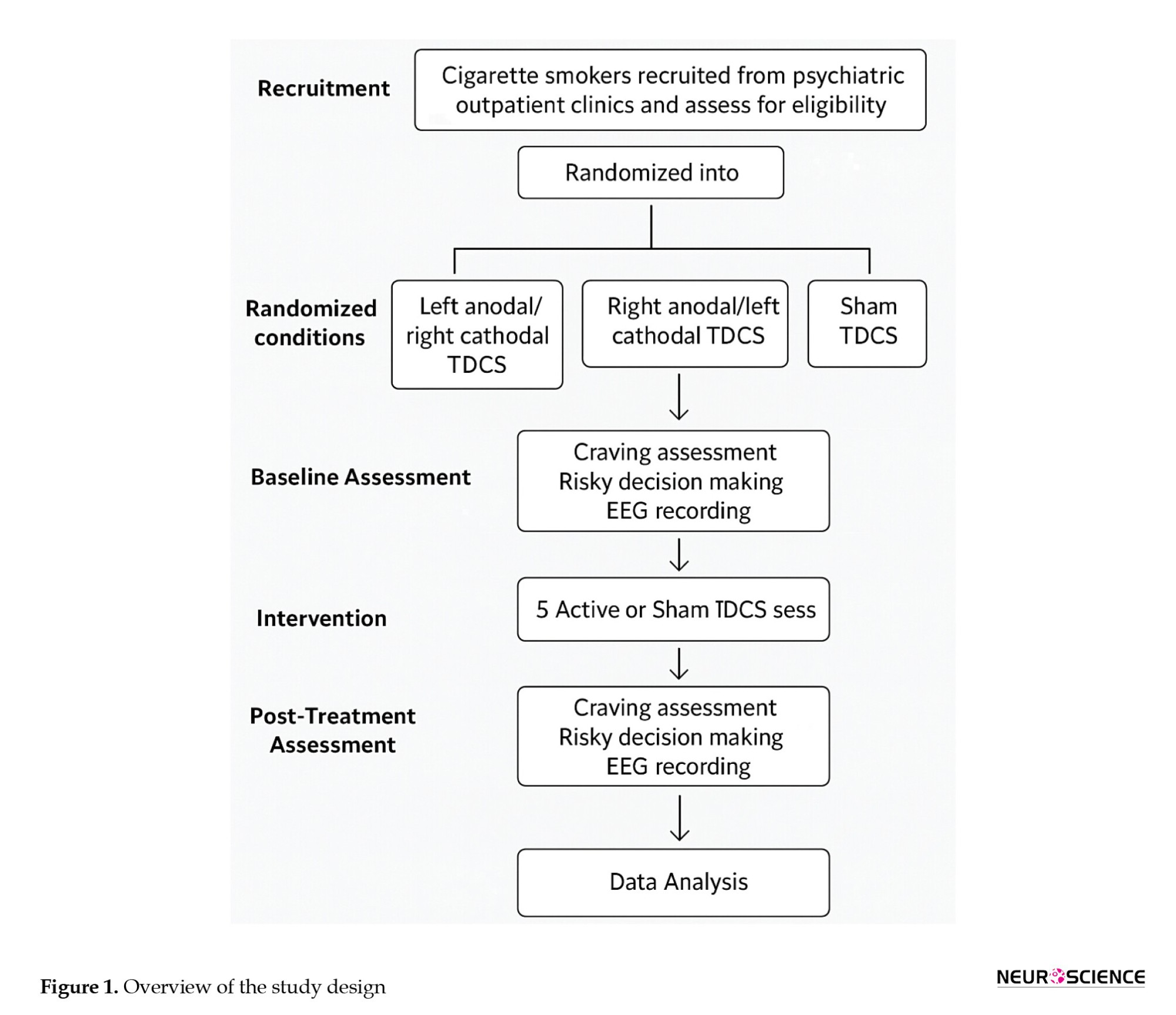

The study will be conducted at Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, located in Mazandaran Province, Iran. The research sample will include individuals from the target population who meet the predefined eligibility criteria. Participants will be recruited via a public announcement targeting interested and eligible individuals. People who express interest and meet the eligibility criteria will be enrolled in the study. Based on Krejcie and Morgan’s sample size determination table (Morgan, 1970), 63 participants are required for this study, assuming unknown population variance and a 50% response probability (Figure 1) (Regner et al., 2018). It should be noted that, in addition to obtaining written informed consent from all participants, the study protocol will incorporate continuous monitoring for any adverse psychological effects that may occur during and after each stimulation session. Participants will be specifically observed for signs of increased anxiety, emotional instability, or discomfort. A licensed clinical psychologist will be present on-site throughout the intervention period to provide immediate evaluation and support if needed. Moreover, participants will be clearly informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without any consequences. These measures are designed to ensure the psychological safety and well-being of all participants throughout the entire experiment.

Participants will be randomly assigned to one of three tDCS conditions (active left, active right, or sham). Craving, risky decision-making, and electroencephalogram will be assessed before and after five stimulation sessions.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible participants will be male cigarette smokers between the ages of 18 and 45 who provide informed consent and are proficient in Persian, including the Mazandarani dialect. Participants must have a history of daily smoking (at least 10 cigarettes per day) for a minimum of 2 years. They must not have any history of head trauma, brain injury, or neurological disorders such as epilepsy, seizures, stroke, or brain/spinal cord tumors. Individuals with metallic implants in the head, visual impairments, or who are currently enrolled in other research studies will be excluded. Participants must also have no current or past psychiatric disorders according to diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria. The decision to include only male participants was based on practical, cultural, and scientific considerations. Prior tDCS studies in addiction research have predominantly focused on males, and cultural sensitivities in Iran, along with limited female volunteerism, pose significant challenges to recruiting a gender-balanced sample.

Furthermore, sex differences in craving, risk-taking, and neural responses may introduce variability in EEG measures; thus, limiting the sample to males improves internal validity. Nonetheless, future studies will aim to include female participants to explore gender-specific effects. Participants will be excluded if they report uncomfortable physical symptoms during testing, have a history of chronic physical illnesses (e.g. multiple sclerosis, diabetes, cardiovascular, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal diseases), psychiatric illness, seizures (regardless of cause), or recent use (within the past 3 months) of psychiatric or anticonvulsant medications. Additionally, individuals with any substance or alcohol abuse history, sleep deprivation the night before testing, or consumption of tea or caffeine within three hours before cognitive testing will be excluded (Bandeira & Mendoza, 2018; O’Donnell, 2007).

Additionally, participants will be informed and provided consent before participating in the study. Subjects must understand, before signing, whether they could be harmed or might benefit from the study. Subjects will be informed that their participation is completely voluntary and that they have the right to withdraw their consent at any time without penalty.

A study information sheet, clearly worded in non-specialist language, will be given to aid participants with differing levels of literacy.

Study intervention

A total of 63 participants who meet the eligibility criteria will be enrolled in the study. Before randomization, demographic and descriptive data will be collected as previously described. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence will be used to assess the degree of nicotine dependence among participants (Diamond et al., 2007; Ekhtiari et al., 2016). The scale includes 6 items reflecting: Time to first cigarette, number of cigarettes per day, the cigarette considered to be most important to the respondent, cigarettes per day smoked, smoking during illness, and smoking in forbidden areas. The scores range from 0 to 10, with 0–4 indicating low dependence, 5–7 moderate dependence, and 8–10 high dependence.

Cue-induced craving measures

In the subsequent stage, participants will be presented with smoking-related pictures to provoke cue-induced craving. The TCQ will rate cravings following exposure. Afterward, participants will undertake the IGT and the BART, followed by EEG recordings.

Brain mapping procedure

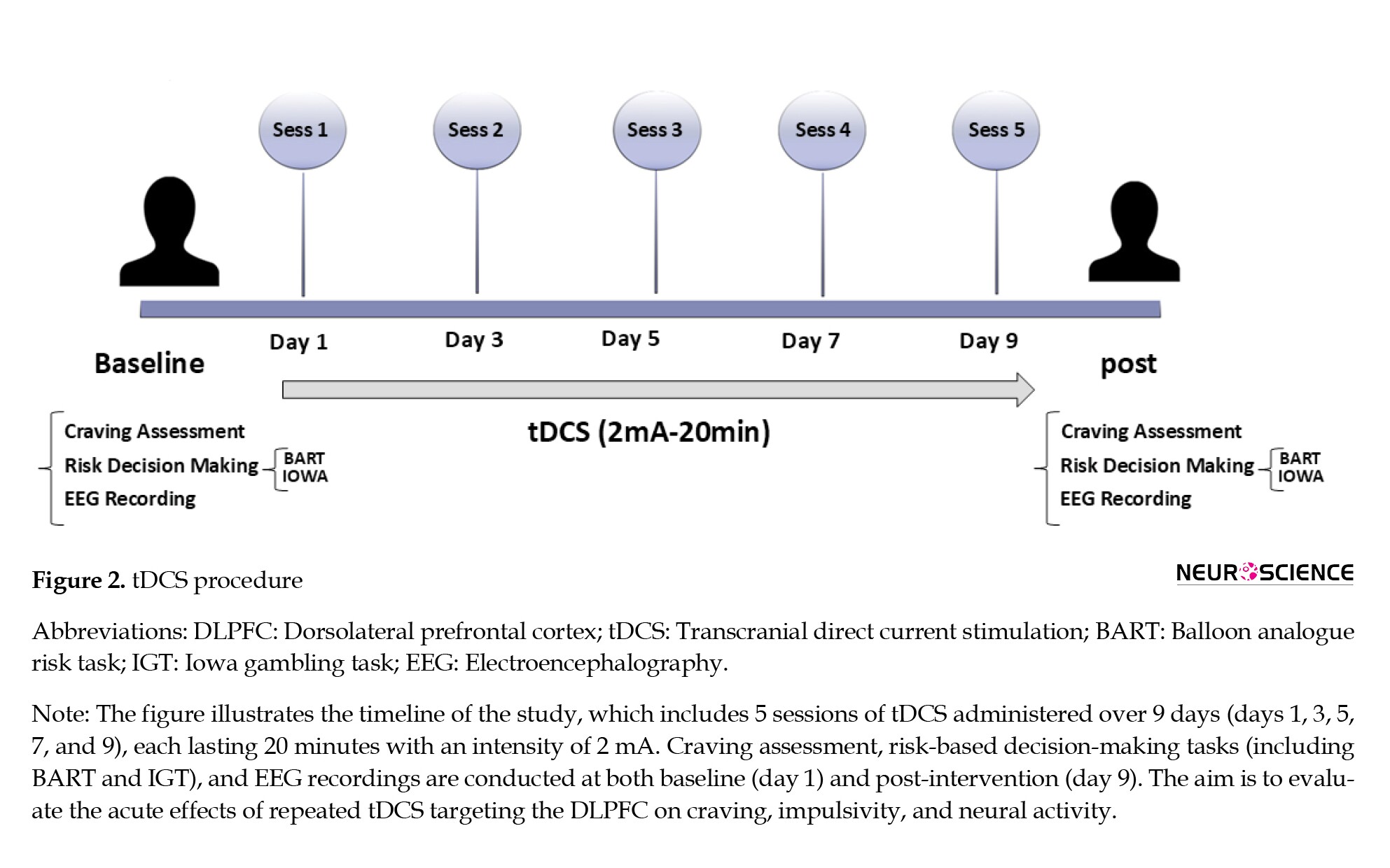

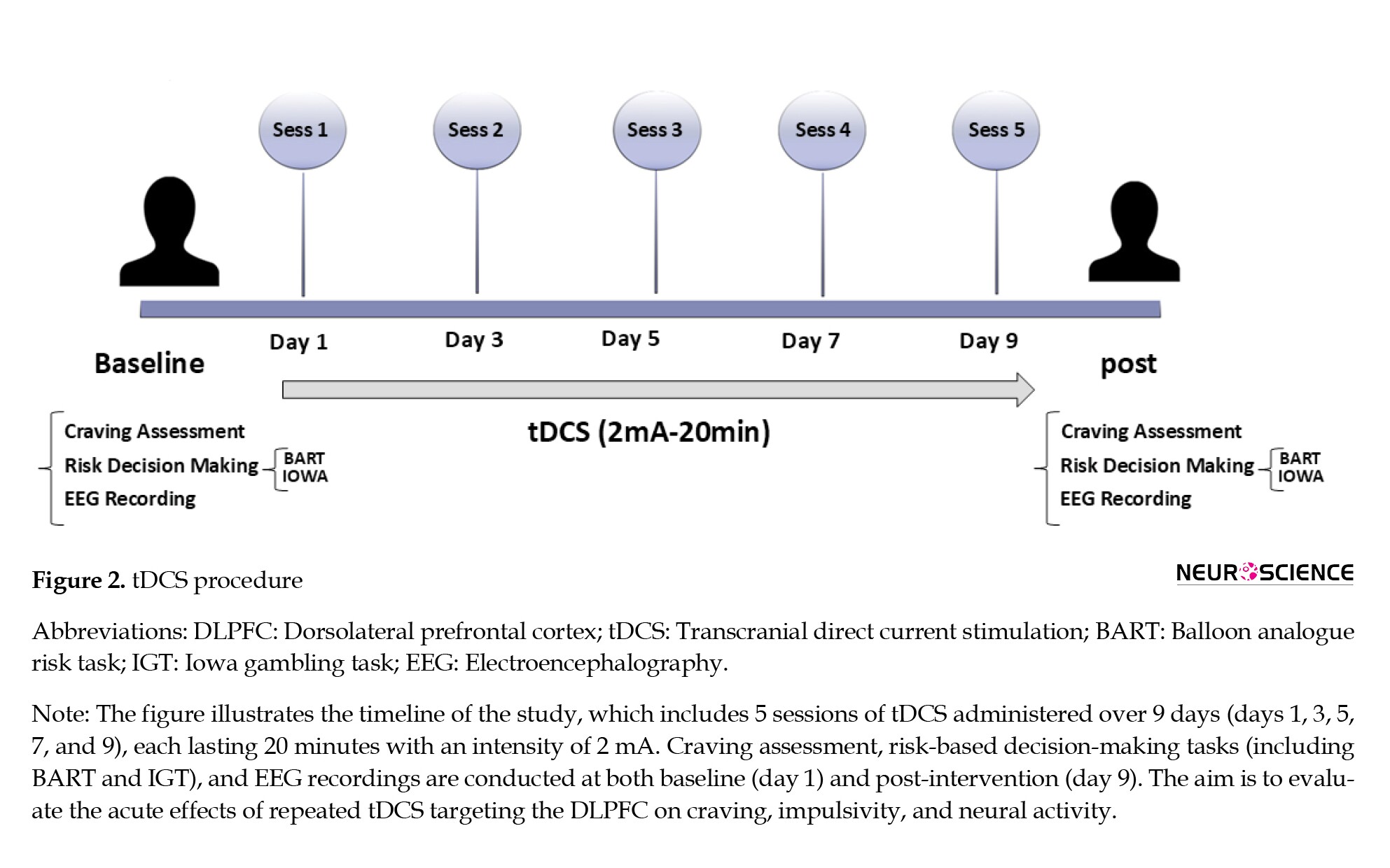

As illustrated in Figure 2, a trained technician, who is blind to the study aims and group allocations, will perform the EEG recordings. After acclimatization, the EEG will be measured under resting conditions.

Participants will be asked to refrain from drinking coffee or tea for at least 3 hours and smoking for 1 hour before the EEG recording.

EEG collection will be performed using a 21-electrode system from MITSAR. We will adhere to the 10–20 system, using an electrocap with a 500 Hz sample rate, an impedance of less than 5 kΩ, a 0.3 Hz low-pass filter, and a 45–55 Hz notch filter.

Collected EEG data will be processed using Python-based tools to eliminate motion and visual artifacts. The collected data will be analyzed using Python software to remove motion and visual artifacts.

BART

The BART is a computerized risk task based on real-world risky behavior. Participants are incentivized to take risks, though too much risk is not beneficial.

This method allows for the assessment of the risk-prone decision-making style of an individual, as well as the way (s)he exaggerates the risk-taking approach in real-life conditions. Low “adjusted values” (the average number of balloon pumps before an explosion) and few “pumps” on the part of the participant in the BART reflect low risk-taking behavior and impulsivity (Beeli et al., 2008; Ekhtiari et al., 2003; Fecteau et al., 2007).

IGT

IGT uses cards to mimic real-life decision-making and consists of four decks of cards (A, B, C, and D): Two decks (C and D) offering long-term advantages and the remaining two (A and B) generating losses.

This activity requires subjects to make judgments by comparing the navigation of the risk-reward of at least one deck to that of all others.

Randomization and blinding

Randomization will be performed through block randomization and random allocation software, ensuring stratification. This approach is called block random allocation and involves creating blocks of subject allocations by regrouping three basic interventions (treatment, control, and placebo) randomly, led by another colleague who is ignorant of the nature of the interventions.

Both participants and assessors will remain blinded to minimize bias regarding the effects of transcranial stimulation.

Participants will be randomized using block randomization and random allocation software.

Intervention groups

The experimental group consisted of three subgroups:

Group 1 includes smokers who will receive tDCS for 20 minutes at an intensity of 2 mA, which targets the left DLPFC, with the cathode electrode placed on the right side.

Group 2 consisted of smokers who received the same duration of tDCS at an intensity of 2 mA to the right DLPFC.

In group 3 (sham), stimulation electrodes are placed on the DLPFC for 30 s without active stimulation.

The participants will undergo five 20-minute sessions using the neurostim device, with electrodes covered by salt-absorbing sponges, scheduled every other day at a power of 2 mA.

To limit any possible bias and to precisely assess the real effects of tDCS, we used a sham stimulation group. This method adheres to standard strategies employed in the growing body of research on tDCS, ensuring proper blinding while controlling for placebo bias.

Study outcomes

Diagnostic interview

Diagnoses will be confirmed via a semi-structured psychiatric diagnostic assessment based on the validated structured clinical interview for DSM mental disorders, which an experienced psychiatrist will conduct according to the DSM-5 criteria.

Demographic data

Basic demographic information, including age, sex, years of education, place of birth, marital status, number of children, financial condition, family history of affective disorders, and household income, will be collected at the time of study entry. Medical comorbidities will be evaluated using the cumulative illness rating scale (CIRS). Psychiatric history data, age at onset of the first depressive episode, number of relapses, and current medication and dosage will also be collected.

Primary outcomes

Craving reduction

The primary outcome will be the difference scores in craving levels (as measured by TCQ) between pre- and post-intervention. We postulate that tDCS of left and right DLPFC significantly decreases the craving scores in smokers of tobacco.

Cigarette consumption

The second outcome will be a decrease in the number of cigarettes smoked per day. This will be measured at baseline, post-intervention, and at follow-up (e.g. 2 and 4 weeks post-treatment).

Secondary outcomes

Risky decision-making

The effects of tDCS on risky decision-making will be evaluated via the IGT and the BART. Performance metrics such as total points earned in the IGT and adjusted values in the BART will be analyzed before and after the intervention.

Cognitive functioning

Global cognitive status will be assessed using the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA), which is expected to reflect changes in cognitive function following the intervention.

EEG frequency power changes

Frequency powers (alpha, beta, theta, delta, and gamma) will be examined using EEG recordings. We hypothesize that tDCS will modulate these frequency bands in the DLPFC area, indicating that alterations in coupling (changes in excitability) of the underlying cortex are related to craving reduction.

Subjective assessments

Craving intensity and subjective mental fatigue will be assessed using a subjective measure of craving and a visual analogue scale (VAS) (before and after each session) to estimate perceived changes in craving intensity and mental fatigue.

Acceptability and tolerability

The acceptability of tDCS as an intervention will be measured through participant feedback collected via the VAS regarding their levels of tension, stress, and anxiety before and after each session. Treatment tolerability will also be assessed by recording any discomfort experienced during the sessions.

Sample size

The sample size for this study was estimated using G*Power software, version 3.1, based on previous research indicating the effectiveness of tDCS in reducing cravings and improving decision-making. For the present study, 63 participants are required (21 in each group). Considering a 20% dropout rate, we aim to recruit a total of 75 participants (25 per group).

Recruitment

The recruitment process begins after approval is obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. Participants will be recruited through advertisements targeting cigarette smokers who meet the eligibility criteria. Interested individuals will undergo screening to confirm their eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in the study protocol.

Assignment of interventions: Allocation

Sequence generation

Block randomization will be used to assign participants to one of three intervention groups: Left anodal/right cathodal tDCS, right anodal/left cathodal tDCS, and sham tDCS. Each block will consist of 8 participants to ensure balanced allocation across groups.

Concealing mechanism

An independent team member not involved in recruitment or assessment will conduct the randomization process and maintain the allocation sequence confidentiality by sealing it in opaque envelopes.

Implementation

The participants will be informed about the study’s purpose and procedures by trained investigators who are not involved in data collection or analysis. After providing informed consent, the participants will be randomized to their respective groups.

Assignment of interventions: Blinding

Who will be blinded

This study employs a double-blind design, in which both participants and assessors are unaware of their group assignments to minimize bias in data collection and analysis.

Procedure for unblinding if needed

If unblinding is necessary due to medical emergencies, the principal investigator will make the final decision regarding unblinding procedures.

Data collection and management

Plans for the assessment and collection of outcomes

A trained clinician investigator who is not involved in the intervention or randomization procedure will perform evaluations at baseline and immediately postintervention.

Participant retention

To prevent dropouts, they will be reminded by short message service or phone before the appointment and paid for travel costs for attending the assessment.

Data management

Information on demographics and health will be maintained securely on a clinical management system (CMS), with the data entered being able to be verified by trained individuals to help minimize the inaccuracy of responses.

Confidentiality

Participant details will be confidential, with ID numbers assigned, to ensure privacy is protected. The state is stored securely, so only authorized individuals have access. No biological samples were collected in this study.

Statistical methods

Statistical methods for primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measurement will be the change in craving levels assessed via the TCQ. A significant reduction in TCQ scores postintervention will indicate the effectiveness of the tDCS intervention. The secondary outcomes are described as changes in cigarette consumption, changes in risky decision-making as measured by the IGT and BART, and changes in EEG frequency power.

Statistical analysis

A 2-way, 2×2 repeated measures analysis of variance will be conducted to examine the effect of group allocation (active tDCS vs. sham tDCS) and time (pre- vs post-intervention) on the set of primary and secondary outcome variables. Post hoc analyses using the Bonferroni correction will be undertaken to adjust for multiple comparisons, with significance levels set at P<0.05 for primary outcomes and P<0.0125 for secondary outcomes.

Interim analyses

Interim analyses will be conducted once approximately half of the participants have been recruited. The study team will review data for any serious adverse effects reported during the intervention or significant deterioration in participants’ mental or physical health. An early termination of the trial would have to be decided upon by the principal investigator in consultation with the Ethics Committee.

Additional statistical analyses

Subgroup analyses may be conducted according to demographic variables such as age, smoking history, etc.to see if the effects of tDCS differ regarding craving and decision-making outcomes.

Methods of analysis to handle protocol non-adherence and missing data

The analyses will be conducted on an intention-to-treat basis; therefore, for missing data, a carry-forward method will be used, possibly the last observation carried forward. Where patterns of missing data are found to be random, multiple imputation techniques will be employed to facilitate more robust statistical analyses.

Plans to give access to the full protocol, participant-level data, and statistical code

The full study protocol will be made available through the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT). Anonymized participant-level data and statistical code can be requested from the principal investigator upon completion of the study.

Oversight and monitoring

Composition of the coordinating centre and trial steering committee

The trial will be overseen by a research management group comprising the principal investigator and coinvestigators, including psychiatrists and neuroscientists from Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. This group will meet monthly to discuss progress and ensure compliance with ethical standards.

Composition of the data monitoring committee, role, and reporting structure

For data monitoring, an independent committee will be composed of a psychiatrist, a methodologist, a statistician, and a data manager. This committee oversees the data collection processes, ensuring they comply with research protocols and reports any issues directly to the principal investigator.

Adverse event reporting and harms

A checklist of potential adverse effects associated with tDCS administration will be developed based on the literature. Participants will be informed about possible side effects during the consent process. Any adverse effects reported during the study will be documented in the CMS, and participants experiencing significant discomfort will be monitored closely by the principal investigator until resolution. Serious adverse events occurring during treatment sessions will mandate the immediate notification of local healthcare professionals, and emergency protocols will be implemented. Any serious adverse events will be reviewed by the principal investigator to be reported to the Ethics Committee.

Frequency and plans for auditing trial conduct

On-site monitoring of the trial’s conduct will be conducted monthly by designated clinical coordinators affiliated with Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences to ensure participant safety and protocol adherence.

Plans for communicating important protocol amendments

Significant amendments to the protocol (such as changes in eligibility criteria or outcome measures) will be discussed by the investigators and submitted to the Ethics Committee for approval before being implemented.

Dissemination plans

The results of this trial will be disseminated among healthcare professionals, researchers, and policymakers through conferences and publication in peer-reviewed journals. The participants will then receive a summary of their results in layman’s terms, accompanied by visual aids to aid their understanding.

Discussion

tDCS is a growing method that uses gentle electric signals to alter the function of specific brain parts, potentially strengthening nerve connections (Mondino et al., 2015). It offers a new way to deal with being too impulsive, different from usual drug treatments. It is safe and easy to use in cases of drug misuse. Recent studies have shown that tDCS affects our thought processes in three primary ways: Activating the right brain area through electrical stimulation, altering key brain chemicals, and improving blood flow and oxygenation in the brain (Groppa et al., 2010; Rango et al., 2008).

Recent human neuroimaging and neurophysiological studies have advanced our understanding of how tDCS modulates brain function in addiction-related behaviors. For example, Kalu et al. (2012) demonstrated that anodal tDCS over the DLPFC enhances cortical excitability and connectivity within executive control networks, which are crucial for regulating craving and impulsivity. Furthermore, a study by Pripfl & Lamm (2015) using combined tDCS and EEG showed modulation of frontal midline theta oscillations, correlating with improved inhibitory control and reduced risk-taking behavior. These findings underscore the role of tDCS in reshaping neural circuits that govern decision-making and craving, supporting the neurobiological rationale for its use in tobacco addiction. Integrating these human-based mechanistic insights with behavioral data enriches the interpretation of tDCS effects and guides optimization of stimulation

tDCS alters synaptic plasticity by influencing N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and modulating the gamma-aminobutyric acid and dopaminergic systems (Fertonani & Miniussi, 2017). It immediately affects regional cerebral blood flow, with anodic stimulation increasing blood flow by approximately 17.1% and cathodic stimulation by 5.6%. After the stimulation session, blood flow returns to baseline levels. Moreover, stimulating the DLPFC with an electrical current of 1–2 mA increases blood flow in related areas, suggesting a role in enhancing awareness and cognitive functions (Thibaut et al., 2019). The DLPFC plays a critical role in risky decision-making by influencing how probabilities are weighted and the subjective valuation of rewards. Downregulating the left DLPFC decreases the likelihood of choosing options with higher expected values, whereas TMS increases distorted probability weighting, suggesting that the left DLPFC weights probabilities more objectively. The DLPFC integrates reward magnitude and probability to assess option value; disrupting it leads to distorted probability weighting and altered perceptions of expected value and risk. In short, the DLPFC evaluates opportunities. The left side of the DLPFC helps individuals avoid taking risks when there is a chance to gain, while the right side leans towards taking risks when there could be a loss, considering the potential reward and its likelihood to make informed decisions about risky choices. As far as we know, this work is the first of its kind to check how tDCS can change craving and risk-taking acts in people who smoke. The findings will contribute to new treatment concepts for smoking cessation and enhance our understanding of the neural mechanisms involved, providing better insights into the cortical brain areas associated with craving and subsequent risky behavior through a combination of EEG and behavioral measures. The point that needs to be considered is that, despite the promising therapeutic potential of tDCS, it will be essential to consider possible psychological side effects, such as transient increases in anxiety, mood fluctuations, or mental fatigue that may arise during or after stimulation sessions. In this study, continuous monitoring protocols will be implemented to detect any adverse psychological reactions promptly. Participants will be regularly assessed for discomfort or changes in affective state using standardized self-report scales and clinical interviews. Any participant exhibiting significant distress will be provided with immediate psychological support, and stimulation sessions will be adjusted or discontinued if necessary to ensure participant safety. These precautions will underscore our commitment to minimizing potential harm and safeguarding mental well-being throughout the intervention.

However, one notable limitation of the present study is the exclusion of female participants, which restricts the generalizability of our findings to the broader population of smokers. This decision was primarily driven by practical and cultural barriers in recruiting female smokers in Iran, especially in studies involving brain stimulation. Furthermore, sex-related hormonal fluctuations may influence neural responses to tDCS and EEG, introducing additional variability. By limiting the sample to males, we aimed to enhance internal validity in this pilot phase. Nevertheless, future studies should aim to include both genders to explore potential sex-specific effects and improve the external validity of the findings. Moreover, we acknowledge that the absence of a follow-up phase represents a significant limitation of the current protocol. Given that this study is designed as an initial pilot protocol, the primary focus was on assessing the immediate, acute effects of tDCS on craving and risky decision-making. However, to fully understand the durability and clinical relevance of these effects, longitudinal follow-up assessments are essential. We have now explicitly addressed this limitation in the manuscript’s limitations section, indicating that future studies will incorporate follow-up phases to evaluate the long-term sustainability and potential clinical benefits of the intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1402.044). All participants will provide written informed consent before participation. The trial is registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), Tehran, Iran (Code: IRCT20230806059051N1).

Funding

This study was supported by the Research Council of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Grant No.: 17548).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, and methodology: Hamed Ghazvini and Saba Niknamfar; Experiments: Saba Niknamfar; Kamaledin Alaedini, Data interpretation: Raheleh Rafaiee, Seyedeh Masoumeh Seyedhosseini Tamijani, and Eisa Nazar; Data analysis: Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini; Supervision: Azarakhsh Mokri, Writing: Saba Niknamfar and Hamed Ghazvini; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Aicotine is the main psychoactive component of cigarette smoke and plays a major role in the global burden of disease. Cigarette smoking, a prevalent form of tobacco use, is a significant public health risk, and it is projected that the number of smokers will increase to 1.7 billion by 202 (Conti & Baldacchino, 2021; WHO, 2020). It is estimated that by 2030, the number of deaths caused by smoking will reach 8 million annually. Additionally, smokers often exhibit behaviors such as risky decision-making (Kekic et al., 2016). Currently, many approaches are used to prevent and manage tobacco addiction. Despite numerous available interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and pharmaceutical treatments, smoking relapse remains a major challenge (Cahill et al., 2013; Stead et al., 2016). Thus, novel strategies such as brain stimulation have been proposed to reduce tobacco cravings and support smoking cessation. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a widely used non-invasive technique for modulating brain function, particularly in individuals with central nervous system (CNS) disorders (Shourmasti et al., 2023). Numerous studies have verified that tDCS can modulate excitability in both superficial and deep brain structures. During tDCS, anodal stimulation increases cortical excitability through neural depolarization, whereas cathodal stimulation reduces it via hyperpolarization (Barr et al., 2008; Garavan & Hester, 2007). Since alterations in the activity of prefrontal regions, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), are associated with drug craving, studies suggest that anodal tDCS may enhance DLPFC activity and thereby reduce craving (Fregni et al., 2008; Huhn et al., 2019). Loss of control over drug-seeking is a well-recognized feature of drug addiction, which is defined as a compulsive drive to seek drugs for acute rewards despite the risk of aversive consequences.

In this manner, dysfunctions within prefrontal cortical circuits, the DLPFC, contribute to impaired decision-making and cognitive evaluation of consequences, which play a key role in compulsive drug-seeking behavior. In addition, several human studies emphasized that drug addiction leads to significant behavioral impairments in tasks related to making risky decisions (Balconi et al., 2014; Gorini et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013). From this perspective, evidence suggests that tDCS applied to frontal regions such as the DLPFC can influence risk-taking behavior. For instance, Gorini et al. (2014) demonstrated that anodal stimulation of the DLPFC modulated risky choices in abstinent, cocaine-dependent individuals. Moreover, to date, few studies have investigated the effects of non-invasive brain stimulation on electroencephalography (EEG) frequency power changes in cigarette smokers. In a study, Pripfl et al. (2014) applied repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to the left DLPFC and reduced nicotine craving and found decreased EEG delta power in cigarette smokers. It appears that a decrease in delta power has been associated with increased activity of the dopaminergic mesolimbic system. Nevertheless, from a neuropsychological perspective, risk-taking and addictive behaviors share several features that influence brain electrical activity. Taken together, this study aims to evaluate and compare the effects of the left and right-sided tDCS over the DLPFC on performance in two risk-taking tasks and EEG frequency power changes in nicotine smokers and control participants.

Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of tDCS on the DLPFC in reducing craving, risky decision-making, and altering EEG power spectra in cigarette smokers. We hypothesize that tDCS can alter EEG frequency power in the DLPFC, thereby decreasing craving and risky decision-making, and ultimately leading to reduced cigarette consumption among smokers.

Specific objectives

To assess the effect of tDCS on nicotine craving in cigarette smokers using the tobacco craving questionnaire (TCQ).

To compare the differential effects of left- versus right-sided DLPFC stimulation on craving intensity.

To examine the effects of left- and right-sided tDCS on risky decision-making behavior using the Iowa gambling task (IGT) and the balloon analogue risk task (BART).

To analyze shifts in the power spectra of the EEG (alpha, beta, theta, delta, and gamma bands) after stimulation of the left and right DLPFC, comparing relative power and dominant brainwave profiles after tDCS in both conditions.

Trial design

This randomized clinical trial includes three parallel arms: An intervention group, a control group, and a sham group. The study aims to evaluate the effects of electrical stimulation on the DLPFC on risky decision-making and brain wave patterns, and craving induction in cigarette smokers. Participants will be randomly assigned to one of the three groups to ensure balanced allocation across study arms. Specific outcome measures will include decision-making tasks and EEG recordings to assess brain wave patterns associated with craving and risk-related behavior. This structured approach enables a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of electrical stimulation in enhancing decision-making compared to sham treatment.

Materials and Methods

Study setting

The study will be conducted at Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, located in Mazandaran Province, Iran. The research sample will include individuals from the target population who meet the predefined eligibility criteria. Participants will be recruited via a public announcement targeting interested and eligible individuals. People who express interest and meet the eligibility criteria will be enrolled in the study. Based on Krejcie and Morgan’s sample size determination table (Morgan, 1970), 63 participants are required for this study, assuming unknown population variance and a 50% response probability (Figure 1) (Regner et al., 2018). It should be noted that, in addition to obtaining written informed consent from all participants, the study protocol will incorporate continuous monitoring for any adverse psychological effects that may occur during and after each stimulation session. Participants will be specifically observed for signs of increased anxiety, emotional instability, or discomfort. A licensed clinical psychologist will be present on-site throughout the intervention period to provide immediate evaluation and support if needed. Moreover, participants will be clearly informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point without any consequences. These measures are designed to ensure the psychological safety and well-being of all participants throughout the entire experiment.

Participants will be randomly assigned to one of three tDCS conditions (active left, active right, or sham). Craving, risky decision-making, and electroencephalogram will be assessed before and after five stimulation sessions.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible participants will be male cigarette smokers between the ages of 18 and 45 who provide informed consent and are proficient in Persian, including the Mazandarani dialect. Participants must have a history of daily smoking (at least 10 cigarettes per day) for a minimum of 2 years. They must not have any history of head trauma, brain injury, or neurological disorders such as epilepsy, seizures, stroke, or brain/spinal cord tumors. Individuals with metallic implants in the head, visual impairments, or who are currently enrolled in other research studies will be excluded. Participants must also have no current or past psychiatric disorders according to diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria. The decision to include only male participants was based on practical, cultural, and scientific considerations. Prior tDCS studies in addiction research have predominantly focused on males, and cultural sensitivities in Iran, along with limited female volunteerism, pose significant challenges to recruiting a gender-balanced sample.

Furthermore, sex differences in craving, risk-taking, and neural responses may introduce variability in EEG measures; thus, limiting the sample to males improves internal validity. Nonetheless, future studies will aim to include female participants to explore gender-specific effects. Participants will be excluded if they report uncomfortable physical symptoms during testing, have a history of chronic physical illnesses (e.g. multiple sclerosis, diabetes, cardiovascular, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal diseases), psychiatric illness, seizures (regardless of cause), or recent use (within the past 3 months) of psychiatric or anticonvulsant medications. Additionally, individuals with any substance or alcohol abuse history, sleep deprivation the night before testing, or consumption of tea or caffeine within three hours before cognitive testing will be excluded (Bandeira & Mendoza, 2018; O’Donnell, 2007).

Additionally, participants will be informed and provided consent before participating in the study. Subjects must understand, before signing, whether they could be harmed or might benefit from the study. Subjects will be informed that their participation is completely voluntary and that they have the right to withdraw their consent at any time without penalty.

A study information sheet, clearly worded in non-specialist language, will be given to aid participants with differing levels of literacy.

Study intervention

A total of 63 participants who meet the eligibility criteria will be enrolled in the study. Before randomization, demographic and descriptive data will be collected as previously described. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence will be used to assess the degree of nicotine dependence among participants (Diamond et al., 2007; Ekhtiari et al., 2016). The scale includes 6 items reflecting: Time to first cigarette, number of cigarettes per day, the cigarette considered to be most important to the respondent, cigarettes per day smoked, smoking during illness, and smoking in forbidden areas. The scores range from 0 to 10, with 0–4 indicating low dependence, 5–7 moderate dependence, and 8–10 high dependence.

Cue-induced craving measures

In the subsequent stage, participants will be presented with smoking-related pictures to provoke cue-induced craving. The TCQ will rate cravings following exposure. Afterward, participants will undertake the IGT and the BART, followed by EEG recordings.

Brain mapping procedure

As illustrated in Figure 2, a trained technician, who is blind to the study aims and group allocations, will perform the EEG recordings. After acclimatization, the EEG will be measured under resting conditions.

Participants will be asked to refrain from drinking coffee or tea for at least 3 hours and smoking for 1 hour before the EEG recording.

EEG collection will be performed using a 21-electrode system from MITSAR. We will adhere to the 10–20 system, using an electrocap with a 500 Hz sample rate, an impedance of less than 5 kΩ, a 0.3 Hz low-pass filter, and a 45–55 Hz notch filter.

Collected EEG data will be processed using Python-based tools to eliminate motion and visual artifacts. The collected data will be analyzed using Python software to remove motion and visual artifacts.

BART

The BART is a computerized risk task based on real-world risky behavior. Participants are incentivized to take risks, though too much risk is not beneficial.

This method allows for the assessment of the risk-prone decision-making style of an individual, as well as the way (s)he exaggerates the risk-taking approach in real-life conditions. Low “adjusted values” (the average number of balloon pumps before an explosion) and few “pumps” on the part of the participant in the BART reflect low risk-taking behavior and impulsivity (Beeli et al., 2008; Ekhtiari et al., 2003; Fecteau et al., 2007).

IGT

IGT uses cards to mimic real-life decision-making and consists of four decks of cards (A, B, C, and D): Two decks (C and D) offering long-term advantages and the remaining two (A and B) generating losses.

This activity requires subjects to make judgments by comparing the navigation of the risk-reward of at least one deck to that of all others.

Randomization and blinding

Randomization will be performed through block randomization and random allocation software, ensuring stratification. This approach is called block random allocation and involves creating blocks of subject allocations by regrouping three basic interventions (treatment, control, and placebo) randomly, led by another colleague who is ignorant of the nature of the interventions.

Both participants and assessors will remain blinded to minimize bias regarding the effects of transcranial stimulation.

Participants will be randomized using block randomization and random allocation software.

Intervention groups

The experimental group consisted of three subgroups:

Group 1 includes smokers who will receive tDCS for 20 minutes at an intensity of 2 mA, which targets the left DLPFC, with the cathode electrode placed on the right side.

Group 2 consisted of smokers who received the same duration of tDCS at an intensity of 2 mA to the right DLPFC.

In group 3 (sham), stimulation electrodes are placed on the DLPFC for 30 s without active stimulation.

The participants will undergo five 20-minute sessions using the neurostim device, with electrodes covered by salt-absorbing sponges, scheduled every other day at a power of 2 mA.

To limit any possible bias and to precisely assess the real effects of tDCS, we used a sham stimulation group. This method adheres to standard strategies employed in the growing body of research on tDCS, ensuring proper blinding while controlling for placebo bias.

Study outcomes

Diagnostic interview

Diagnoses will be confirmed via a semi-structured psychiatric diagnostic assessment based on the validated structured clinical interview for DSM mental disorders, which an experienced psychiatrist will conduct according to the DSM-5 criteria.

Demographic data

Basic demographic information, including age, sex, years of education, place of birth, marital status, number of children, financial condition, family history of affective disorders, and household income, will be collected at the time of study entry. Medical comorbidities will be evaluated using the cumulative illness rating scale (CIRS). Psychiatric history data, age at onset of the first depressive episode, number of relapses, and current medication and dosage will also be collected.

Primary outcomes

Craving reduction

The primary outcome will be the difference scores in craving levels (as measured by TCQ) between pre- and post-intervention. We postulate that tDCS of left and right DLPFC significantly decreases the craving scores in smokers of tobacco.

Cigarette consumption

The second outcome will be a decrease in the number of cigarettes smoked per day. This will be measured at baseline, post-intervention, and at follow-up (e.g. 2 and 4 weeks post-treatment).

Secondary outcomes

Risky decision-making

The effects of tDCS on risky decision-making will be evaluated via the IGT and the BART. Performance metrics such as total points earned in the IGT and adjusted values in the BART will be analyzed before and after the intervention.

Cognitive functioning

Global cognitive status will be assessed using the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA), which is expected to reflect changes in cognitive function following the intervention.

EEG frequency power changes

Frequency powers (alpha, beta, theta, delta, and gamma) will be examined using EEG recordings. We hypothesize that tDCS will modulate these frequency bands in the DLPFC area, indicating that alterations in coupling (changes in excitability) of the underlying cortex are related to craving reduction.

Subjective assessments

Craving intensity and subjective mental fatigue will be assessed using a subjective measure of craving and a visual analogue scale (VAS) (before and after each session) to estimate perceived changes in craving intensity and mental fatigue.

Acceptability and tolerability

The acceptability of tDCS as an intervention will be measured through participant feedback collected via the VAS regarding their levels of tension, stress, and anxiety before and after each session. Treatment tolerability will also be assessed by recording any discomfort experienced during the sessions.

Sample size

The sample size for this study was estimated using G*Power software, version 3.1, based on previous research indicating the effectiveness of tDCS in reducing cravings and improving decision-making. For the present study, 63 participants are required (21 in each group). Considering a 20% dropout rate, we aim to recruit a total of 75 participants (25 per group).

Recruitment

The recruitment process begins after approval is obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. Participants will be recruited through advertisements targeting cigarette smokers who meet the eligibility criteria. Interested individuals will undergo screening to confirm their eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in the study protocol.

Assignment of interventions: Allocation

Sequence generation

Block randomization will be used to assign participants to one of three intervention groups: Left anodal/right cathodal tDCS, right anodal/left cathodal tDCS, and sham tDCS. Each block will consist of 8 participants to ensure balanced allocation across groups.

Concealing mechanism

An independent team member not involved in recruitment or assessment will conduct the randomization process and maintain the allocation sequence confidentiality by sealing it in opaque envelopes.

Implementation

The participants will be informed about the study’s purpose and procedures by trained investigators who are not involved in data collection or analysis. After providing informed consent, the participants will be randomized to their respective groups.

Assignment of interventions: Blinding

Who will be blinded

This study employs a double-blind design, in which both participants and assessors are unaware of their group assignments to minimize bias in data collection and analysis.

Procedure for unblinding if needed

If unblinding is necessary due to medical emergencies, the principal investigator will make the final decision regarding unblinding procedures.

Data collection and management

Plans for the assessment and collection of outcomes

A trained clinician investigator who is not involved in the intervention or randomization procedure will perform evaluations at baseline and immediately postintervention.

Participant retention

To prevent dropouts, they will be reminded by short message service or phone before the appointment and paid for travel costs for attending the assessment.

Data management

Information on demographics and health will be maintained securely on a clinical management system (CMS), with the data entered being able to be verified by trained individuals to help minimize the inaccuracy of responses.

Confidentiality

Participant details will be confidential, with ID numbers assigned, to ensure privacy is protected. The state is stored securely, so only authorized individuals have access. No biological samples were collected in this study.

Statistical methods

Statistical methods for primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome measurement will be the change in craving levels assessed via the TCQ. A significant reduction in TCQ scores postintervention will indicate the effectiveness of the tDCS intervention. The secondary outcomes are described as changes in cigarette consumption, changes in risky decision-making as measured by the IGT and BART, and changes in EEG frequency power.

Statistical analysis

A 2-way, 2×2 repeated measures analysis of variance will be conducted to examine the effect of group allocation (active tDCS vs. sham tDCS) and time (pre- vs post-intervention) on the set of primary and secondary outcome variables. Post hoc analyses using the Bonferroni correction will be undertaken to adjust for multiple comparisons, with significance levels set at P<0.05 for primary outcomes and P<0.0125 for secondary outcomes.

Interim analyses

Interim analyses will be conducted once approximately half of the participants have been recruited. The study team will review data for any serious adverse effects reported during the intervention or significant deterioration in participants’ mental or physical health. An early termination of the trial would have to be decided upon by the principal investigator in consultation with the Ethics Committee.

Additional statistical analyses

Subgroup analyses may be conducted according to demographic variables such as age, smoking history, etc.to see if the effects of tDCS differ regarding craving and decision-making outcomes.

Methods of analysis to handle protocol non-adherence and missing data

The analyses will be conducted on an intention-to-treat basis; therefore, for missing data, a carry-forward method will be used, possibly the last observation carried forward. Where patterns of missing data are found to be random, multiple imputation techniques will be employed to facilitate more robust statistical analyses.

Plans to give access to the full protocol, participant-level data, and statistical code

The full study protocol will be made available through the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT). Anonymized participant-level data and statistical code can be requested from the principal investigator upon completion of the study.

Oversight and monitoring

Composition of the coordinating centre and trial steering committee

The trial will be overseen by a research management group comprising the principal investigator and coinvestigators, including psychiatrists and neuroscientists from Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. This group will meet monthly to discuss progress and ensure compliance with ethical standards.

Composition of the data monitoring committee, role, and reporting structure

For data monitoring, an independent committee will be composed of a psychiatrist, a methodologist, a statistician, and a data manager. This committee oversees the data collection processes, ensuring they comply with research protocols and reports any issues directly to the principal investigator.

Adverse event reporting and harms

A checklist of potential adverse effects associated with tDCS administration will be developed based on the literature. Participants will be informed about possible side effects during the consent process. Any adverse effects reported during the study will be documented in the CMS, and participants experiencing significant discomfort will be monitored closely by the principal investigator until resolution. Serious adverse events occurring during treatment sessions will mandate the immediate notification of local healthcare professionals, and emergency protocols will be implemented. Any serious adverse events will be reviewed by the principal investigator to be reported to the Ethics Committee.

Frequency and plans for auditing trial conduct

On-site monitoring of the trial’s conduct will be conducted monthly by designated clinical coordinators affiliated with Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences to ensure participant safety and protocol adherence.

Plans for communicating important protocol amendments

Significant amendments to the protocol (such as changes in eligibility criteria or outcome measures) will be discussed by the investigators and submitted to the Ethics Committee for approval before being implemented.

Dissemination plans

The results of this trial will be disseminated among healthcare professionals, researchers, and policymakers through conferences and publication in peer-reviewed journals. The participants will then receive a summary of their results in layman’s terms, accompanied by visual aids to aid their understanding.

Discussion

tDCS is a growing method that uses gentle electric signals to alter the function of specific brain parts, potentially strengthening nerve connections (Mondino et al., 2015). It offers a new way to deal with being too impulsive, different from usual drug treatments. It is safe and easy to use in cases of drug misuse. Recent studies have shown that tDCS affects our thought processes in three primary ways: Activating the right brain area through electrical stimulation, altering key brain chemicals, and improving blood flow and oxygenation in the brain (Groppa et al., 2010; Rango et al., 2008).

Recent human neuroimaging and neurophysiological studies have advanced our understanding of how tDCS modulates brain function in addiction-related behaviors. For example, Kalu et al. (2012) demonstrated that anodal tDCS over the DLPFC enhances cortical excitability and connectivity within executive control networks, which are crucial for regulating craving and impulsivity. Furthermore, a study by Pripfl & Lamm (2015) using combined tDCS and EEG showed modulation of frontal midline theta oscillations, correlating with improved inhibitory control and reduced risk-taking behavior. These findings underscore the role of tDCS in reshaping neural circuits that govern decision-making and craving, supporting the neurobiological rationale for its use in tobacco addiction. Integrating these human-based mechanistic insights with behavioral data enriches the interpretation of tDCS effects and guides optimization of stimulation

tDCS alters synaptic plasticity by influencing N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and modulating the gamma-aminobutyric acid and dopaminergic systems (Fertonani & Miniussi, 2017). It immediately affects regional cerebral blood flow, with anodic stimulation increasing blood flow by approximately 17.1% and cathodic stimulation by 5.6%. After the stimulation session, blood flow returns to baseline levels. Moreover, stimulating the DLPFC with an electrical current of 1–2 mA increases blood flow in related areas, suggesting a role in enhancing awareness and cognitive functions (Thibaut et al., 2019). The DLPFC plays a critical role in risky decision-making by influencing how probabilities are weighted and the subjective valuation of rewards. Downregulating the left DLPFC decreases the likelihood of choosing options with higher expected values, whereas TMS increases distorted probability weighting, suggesting that the left DLPFC weights probabilities more objectively. The DLPFC integrates reward magnitude and probability to assess option value; disrupting it leads to distorted probability weighting and altered perceptions of expected value and risk. In short, the DLPFC evaluates opportunities. The left side of the DLPFC helps individuals avoid taking risks when there is a chance to gain, while the right side leans towards taking risks when there could be a loss, considering the potential reward and its likelihood to make informed decisions about risky choices. As far as we know, this work is the first of its kind to check how tDCS can change craving and risk-taking acts in people who smoke. The findings will contribute to new treatment concepts for smoking cessation and enhance our understanding of the neural mechanisms involved, providing better insights into the cortical brain areas associated with craving and subsequent risky behavior through a combination of EEG and behavioral measures. The point that needs to be considered is that, despite the promising therapeutic potential of tDCS, it will be essential to consider possible psychological side effects, such as transient increases in anxiety, mood fluctuations, or mental fatigue that may arise during or after stimulation sessions. In this study, continuous monitoring protocols will be implemented to detect any adverse psychological reactions promptly. Participants will be regularly assessed for discomfort or changes in affective state using standardized self-report scales and clinical interviews. Any participant exhibiting significant distress will be provided with immediate psychological support, and stimulation sessions will be adjusted or discontinued if necessary to ensure participant safety. These precautions will underscore our commitment to minimizing potential harm and safeguarding mental well-being throughout the intervention.

However, one notable limitation of the present study is the exclusion of female participants, which restricts the generalizability of our findings to the broader population of smokers. This decision was primarily driven by practical and cultural barriers in recruiting female smokers in Iran, especially in studies involving brain stimulation. Furthermore, sex-related hormonal fluctuations may influence neural responses to tDCS and EEG, introducing additional variability. By limiting the sample to males, we aimed to enhance internal validity in this pilot phase. Nevertheless, future studies should aim to include both genders to explore potential sex-specific effects and improve the external validity of the findings. Moreover, we acknowledge that the absence of a follow-up phase represents a significant limitation of the current protocol. Given that this study is designed as an initial pilot protocol, the primary focus was on assessing the immediate, acute effects of tDCS on craving and risky decision-making. However, to fully understand the durability and clinical relevance of these effects, longitudinal follow-up assessments are essential. We have now explicitly addressed this limitation in the manuscript’s limitations section, indicating that future studies will incorporate follow-up phases to evaluate the long-term sustainability and potential clinical benefits of the intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1402.044). All participants will provide written informed consent before participation. The trial is registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), Tehran, Iran (Code: IRCT20230806059051N1).

Funding

This study was supported by the Research Council of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Grant No.: 17548).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, study design, and methodology: Hamed Ghazvini and Saba Niknamfar; Experiments: Saba Niknamfar; Kamaledin Alaedini, Data interpretation: Raheleh Rafaiee, Seyedeh Masoumeh Seyedhosseini Tamijani, and Eisa Nazar; Data analysis: Seyed Hamzeh Hosseini; Supervision: Azarakhsh Mokri, Writing: Saba Niknamfar and Hamed Ghazvini; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Balconi, M., Finocchiaro, R., & Canavesio, Y. (2014). Reward-system effect (BAS rating), left hemispheric "unbalance" (alpha band oscillations) and decisional impairments in drug addiction. Addictive Behaviors, 39(6), 1026–1032. [DOI:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.007] [PMID]

Bandeira, I. D., & Mendoza, J. (2018). Medical education and leadership: A call to action for Brazil's mental health system. International Journal of Medical Education, 9, 170–172.[DOI:10.5116/ijme.5b1b.b0a2] [PMID]

Barr, M. S., Fitzgerald, P. B., Farzan, F., George, T. P., & Daskalakis, Z. J. (2008). Transcranial magnetic stimulation to understand the pathophysiology and treatment of substance use disorders. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 1(3), 328–339.[DOI:10.2174/1874473710801030328] [PMID]

Beeli, G., Koeneke, S., Gasser, K., & Jancke, L. (2008). Brain stimulation modulates driving behavior. Behavioral and Brain Functions: BBF, 4, 34. [DOI:10.1186/1744-9081-4-34] [PMID]

Cahill, K., Stevens, S., Perera, R., & Lancaster, T. (2013). Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(5), CD009329. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2] [PMID]

Conti, A. A., & Baldacchino, A. M. (2021). Neuroanatomical correlates of impulsive choices and risky decision making in young chronic tobacco smokers: A voxel-based morphometry study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 708925. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.708925] [PMID]

Diamond, D. M., Campbell, A. M., Park, C. R., Halonen, J., & Zoladz, P. R. (2007). The temporal dynamics model of emotional memory processing: A synthesis on the neurobiological basis of stress-induced amnesia, flashbulb and traumatic memories, and the Yerkes-Dodson law. Neural Plasticity, 2007, 60803. [DOI:10.1155/2007/60803] [PMID]

Ekhtiari, H., Janati, A., Moghimi, A., & Behzadi, A. (2003). [The Farsi Version of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task: An Instrument for the Assessment of Riskful-Decision Making (Persian)]. Advances in Cognitive Sciences, 4(4), 9-11. [Link]

Ekhtiari, H., Nasseri, P., Yavari, F., Mokri, A., & Monterosso, J. (2016). Neuroscience of drug craving for addiction medicine: From circuits to therapies. Progress in Brain Research, 223, 115-141. [DOI:10.1016/bs.pbr.2015.10.002] [PMID]

Fecteau, S., Knoch, D., Fregni, F., Sultani, N., Boggio, P., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2007). Diminishing risk-taking behavior by modulating activity in the prefrontal cortex: A direct current stimulation study. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(46), 12500-12505. [DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3283-07.2007] [PMID]

Fertonani, A., & Miniussi, C. (2017). Transcranial electrical stimulation: what we know and do not know about mechanisms. The Neuroscientist, 23(2), 109-123. [DOI:10.1177/1073858416631966] [PMID]

Fregni, F., Liguori, P., Fecteau, S., Nitsche, M. A., Pascual-Leone, A., & Boggio, P. S. (2008). Cortical stimulation of the prefrontal cortex with transcranial direct current stimulation reduces cue-provoked smoking craving: A randomized, sham-controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(1), 32-40. [DOI:10.4088/JCP.v69n0105] [PMID]

Garavan, H., & Hester, R. (2007). The role of cognitive control in cocaine dependence. Neuropsychology Review, 17(3), 337-345. [DOI:10.1007/s11065-007-9034-x] [PMID]

Gorini, A., Lucchiari, C., Russell-Edu, W., & Pravettoni, G. (2014). Modulation of risky choices in recently abstinent dependent cocaine users: A transcranial direct-current stimulation study. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 661. [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00661] [PMID]

Groppa, S., Bergmann, T., Siems, C., Mölle, M., Marshall, L., & Siebner, H. (2010). Slow-oscillatory transcranial direct current stimulation can induce bidirectional shifts in motor cortical excitability in awake humans. Neuroscience, 166(4), 1219-1225. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.019] [PMID]

Huhn, A. S., Sweeney, M. M., Brooner, R. K., Kidorf, M. S., Tompkins, D. A., & Ayaz, H., et al. (2019). Prefrontal cortex response to drug cues, craving, and current depressive symptoms are associated with treatment outcomes in methadone-maintained patients. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44(4), 826-833. [DOI:10.1038/s41386-018-0252-0] [PMID]

Kalu, U. G., Sexton, C. E., Loo, C. K., & Ebmeier, K. P. (2012). Transcranial direct current stimulation in the treatment of major depression: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 42(9), 1791-1800. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291711003059] [PMID]

Kekic, M., Boysen, E., Campbell, I. C., & Schmidt, U. (2016). A systematic review of the clinical efficacy of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in psychiatric disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 74, 70-86. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.12.018] [PMID]

Mondino, M., Brunelin, J., Palm, U., R Brunoni, A., Poulet, E., & Fecteau, S. (2015). Transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of refractory symptoms of schizophrenia. Current Evidence and Future Directions. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 21(23), 3373-3383. [DOI:10.2174/1381612821666150619093648] [PMID]

Morgan, K. (1970). Sample size determination using Krejcie and Morgan table. Kenya Projects Organization (KENPRO), 38(1970), 607-610. [Link]

O'Donnell, O. (2007). Access to health care in developing countries: breaking down demand side barriers. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 23(12), 2820–2834. [DOI:10.1590/S0102-311X2007001200003] [PMID]

Pripfl, J., & Lamm, C. (2015). Focused transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex modulates specific domains of self-regulation. Neuroscience Research, 91, 41-47. [DOI:10.1016/j.neures.2014.09.007] [PMID]

Pripfl, J., Tomova, L., Riecansky, I., & Lamm, C. (2014). Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex decreases cue-induced nicotine craving and EEG delta power. Brain Stimulation, 7(2), 226-233. [DOI:10.1016/j.brs.2013.11.003] [PMID]

Rango, M., Cogiamanian, F., Marceglia, S., Barberis, B., Arighi, A., & Biondetti, P., et al. (2008). Myoinositol content in the human brain is modified by transcranial direct current stimulation in a matter of minutes: A 1H‐MRS study. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 60(4), 782-789. [DOI:10.1002/mrm.21709] [PMID]

Regner, G. G., Pereira, P., Leffa, D. T., de Oliveira, C., Vercelino, R., & Fregni, F., et al. (2018). Preclinical to clinical translation of studies of transcranial direct-current stimulation in the treatment of epilepsy: A systematic review. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, 189. [DOI:10.3389/fnins.2018.00189] [PMID]

Shourmasti, F. R., Khodamoradi, M., Tamijani, S. M. S., Rafaiee, R., de Vasconcelos, C. A. C., & Mohammadi, H., et al. (2023). The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer›s Disease: A narrative review. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, 27(2), e136442. [DOI:10.5812/jkums-136442]

Stead, L. F., Koilpillai, P., Fanshawe, T. R., & Lancaster, T. (2016). Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3(3), CD008286. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008286.pub3] [PMID]

Thibaut, A., Schiff, N., Giacino, J., Laureys, S., & Gosseries, O. (2019). Therapeutic interventions in patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness. The Lancet Neurology, 18(6), 600-614. [DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30031-6] [PMID]

Wang, G., Shi, J., Chen, N., Xu, L., Li, J., & Li, P., et al. (2013). Effects of length of abstinence on decision-making and craving in methamphetamine abusers. Plos One, 8(7), e68791.[DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0068791] [PMID]

WHO (2020). WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use 2000-2025. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Link]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Behavioral Neuroscience

Received: 2025/07/1 | Accepted: 2025/07/12 | Published: 2025/09/19

Received: 2025/07/1 | Accepted: 2025/07/12 | Published: 2025/09/19

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |