Volume 16, Issue 6 (November & December 2025)

BCN 2025, 16(6): 1131-1142 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Vosoughian F, Khodagholi F, Zeinaddini-Meymand A, Mousavi M A, Karimi R, Rasooli T, et al . Promoting Mental Well-being in Iranian Children: Assessing the Impact of a Philosophy for Children Program Through Behavioral Evaluation. BCN 2025; 16 (6) :1131-1142

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3159-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-3159-en.html

Fatemeh Vosoughian1

, Fariba Khodagholi1

, Fariba Khodagholi1

, Arman Zeinaddini-Meymand1

, Arman Zeinaddini-Meymand1

, Maryam Alsadat Mousavi1

, Maryam Alsadat Mousavi1

, Roohollah Karimi2

, Roohollah Karimi2

, Taravat Rasooli3

, Taravat Rasooli3

, Fereshteh Khodagholi3

, Fereshteh Khodagholi3

, Yahya Ghaedi4

, Yahya Ghaedi4

, Saba Amiri *1

, Saba Amiri *1

, Fariba Khodagholi1

, Fariba Khodagholi1

, Arman Zeinaddini-Meymand1

, Arman Zeinaddini-Meymand1

, Maryam Alsadat Mousavi1

, Maryam Alsadat Mousavi1

, Roohollah Karimi2

, Roohollah Karimi2

, Taravat Rasooli3

, Taravat Rasooli3

, Fereshteh Khodagholi3

, Fereshteh Khodagholi3

, Yahya Ghaedi4

, Yahya Ghaedi4

, Saba Amiri *1

, Saba Amiri *1

1- Neuroscience Research Center, Institute of Neuroscience and Cognition, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, Ethics and Training, Tehran, Iran.

3- Neurobiology Research Center, Institute of Neuroscience and Cognition, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Educational Philosophy, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, Ethics and Training, Tehran, Iran.

3- Neurobiology Research Center, Institute of Neuroscience and Cognition, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Educational Philosophy, Kharazmi University, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Philosophy for children (P4C), Mental well-being, Conduct problems, Social problems, Inattention, Hyperactivity, Anxiety

Full-Text [PDF 634 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

Introduction

Childhood is crucial for developing social, emotional, and intellectual abilities. This is due to the high level of brain malleability during this time, which facilitates learning and adjusting to one’s surroundings (Gabard-Durnam & McLaughlin, 2020; Kolb & Gibb, 2014). Cognitive ability is the human mind’s capacity to extract, process, store, communicate, and reproduce information from the external world (Yan & Li, 2023). Cognitive ability typically includes verbal, numerical, technological proficiency, and logical reasoning skills (Hunter, 1986). Individuals with lower cognitive performance during youth have an increased likelihood of mental health problems many years later (Gale et al., 2012). Cognitive difficulties may involve problems with focus, information recall, scheduling, organizing, logical reasoning, and problem-solving. These cognitive skills are essential for numerous functional duties, such as employment, education, social interactions, community participation, and independent living (Clements & Karmas, 2015). Children and adolescents with higher intelligence test scores are generally less likely to be diagnosed with depressive or anxiety disorders or to report indications (signs) of psychological suffering later in life (Hatch et al., 2007; Koenen et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2007). These issues represent only one extreme of the broad spectrum of mental well-being. Due to the significant scientific and societal implications, the possibility of improving cognitive skills through training and interventions has been one of the most influential topics in cognitive psychology. Research has shown that digital education technology can stimulate students’ intrinsic motivation, inspire them to learn, and improve their cognitive skills (Yan & Li, 2023). Moreover, studies have explored the intricate relationship between working memory (WM) and overall cognition, suggesting that targeted WM training could lead to significant cognitive improvements across various domains (Morrison & Chein, 2011). Other interventions, such as dance (Kein et al., 2000), music (Schellenberg et al., 2007), and chess (Sala & Gobet, 2016) in addition to using media, such as pop-up book learning media (Dian Idha & Rukiyati, 2018), have been hypothesized to impact cognitive ability.

Given the undeniable shortcomings of prevalent methods, most countries seek to develop approaches that cultivate thinking, creativity, and problem-solving. Therefore, diverse educational methods have emerged, including creative thinking, critical thinking, problem-solving skills, innovative curricula, and philosophy programs for children (Hogan, 2006).

The practice of “philosophy for children” (P4C) is considered one of the initial tools for developing thinking abilities (Zulkifli & Hashim, 2020). The use of P4C is becoming increasingly widespread in school settings, particularly to promote youth well-being. Lipman is known for founding P4C in the 1970s and holds the belief that philosophical thinking can be taught at any age (Khanmohammadi et al., 2020). This educational program is designed to promote critical thinking, caring, creative reasoning, and inquiry within the educational environment (Lipman, 1985; Vansieleghem & Kennedy, 2011). Lipman explains that P4C aims to broaden the scope of philosophy by using it as a pedagogical tool. In this teaching method, philosophy is employed to stimulate children’s innate desire and interest in seeking meaning and understanding (Lipman, 2003). The educational material in programs that utilize this philosophical approach consists of philosophical stories, and the processes are focused on communities of inquiry. The term “inquiry” is chosen over “lesson” because the focus is on the group investigating questions together with the teacher acting as a facilitator rather than an authoritative source of information (Bleazby, 2013). Throughout P4C exercises, students are provided with an existential or philosophical subject when they read a story, watch a short video, or select themes (Lipman, 2010). P4C incorporates discussion as a primary element. In addition, in a community of inquiry, learners have the opportunity to deeply reflect on and assess several concepts. Class exploration circles provide an environment for learners to develop emotionally and socially in addition to their cognitive and political growth (Haynes, 2008). In these circumstances, they can have actual discussions, respect one another, build on ever-increasing sense of confidence, and increase their ability to communicate at different levels. Through P4C, children can learn to be more thoughtful, adaptable, considerate, and logical (Khanmohammadi et al., 2020).

Childhood mental health issues have significant adverse effects on individuals, families, and society (Ogundele, 2018). Consequently, it is imperative to promptly address many issues that children may encounter, including anxiety, conduct problems, and symptoms, such as hyperactivity and inattention. Various interventions have been used to mitigate the issues described above (Fisak et al., 2023; Gardner et al., 2006; Salartash et al., 2022). The current study set out to assess the effect of the P4C intervention on children’s social problems, including items, such as being unaccepted, being isolated, having no fair play, lacking leadership, having trouble with the same sex, being uncooperative and easily led, conduct problems, including items, such as being impudent, lying, being destructive, being quarrelsome, stealing, disturbing, teasing, and acting wise. Other factors include hyperactivity, anxiety, and inattention symptoms (Rezai et al., 2015).

Materials and Methods

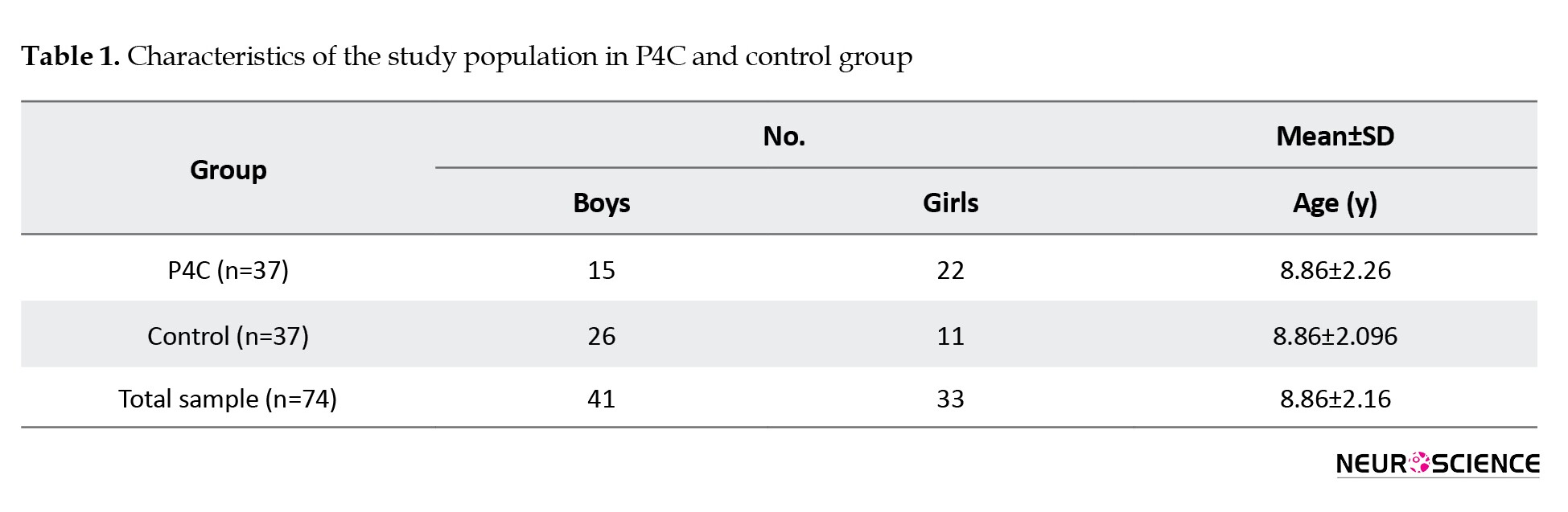

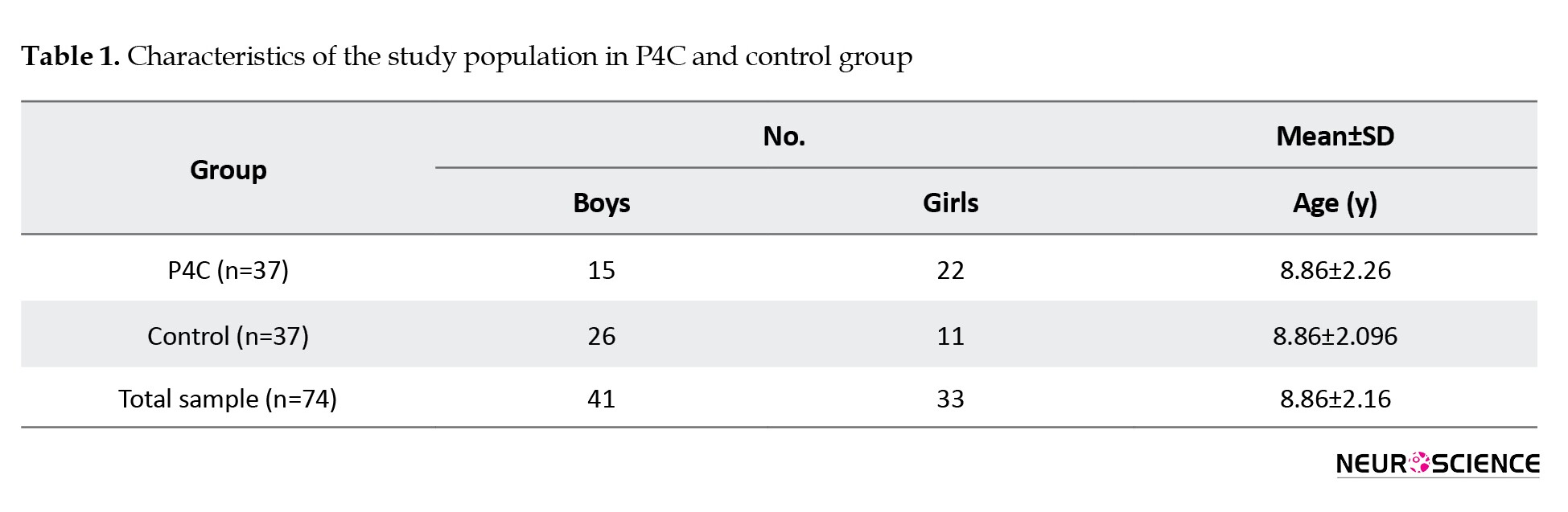

The current study enrolled 74 Iranian children (41 boys and 33 girls) with a Mean±SD age of 8.86±2.16 years (range: 6–13 years). According to reports from teachers and parents, no clinical diagnosis of psychiatric disorders has been reported. They were then randomly categorized into two groups: Control and P4C (Table 1). The Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran, approved this study. Both the participants’ legal guardians or next of kin and the participating teachers provided informed consent to participate in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant Helsinki guidelines and regulations.

Instruments

Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP-IV)

The SNAP-IV is an 18-item scale (Swanson, 1992; Swanson et al., 1983) and that is commonly used to evaluate the main symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Hall et al., 2019) in both ADHD (Luo et al., 2022) and healthy communities (Öner et al., 2019). This questionnaire uses a 4-point Likert scale from not at all (0) to very much (3) to assess the following factors: Hyperactivity/impulsivity (9 items), inattention (9 items), and combined (both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive) (18 items). SNAP has high reliability and validity (Bussing et al., 2008). The questionnaire has been modified for Iranian society (Sadr Alsadat et al., 2009). Sadr-Alsadat reported a test re-test reliability of 82% for the teacher form, with Cronbach’s α coefficients at 90% (Sadr alsadat et al., 2008).

Connors teacher rating scale (CTRS)

The CTRS, originally developed in 1968 with 39 items (Conners, 1969), remains a valuable and accurate tool for evaluating behavioral issues in children and teenagers. This multiple-choice questionnaire uses a Likert scale, with possible answers ranging from 0 (never or very rarely) to 3 (always or most of the time). This questionnaire has been adjusted for Iranian society (Rezai et al., 2015). Connors (1969) reported that the test re-test reliability of the teacher form ranged from 72% to 92% over a month to a year, and that 70% of the teachers’ scoring reliability was also reported. The cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 61% to 95% (Shahim et al., 2008).

Procedure

The participants were randomly categorized into two groups. The intervention group comprised 37 children who participated in weekly 1-hour P4C sessions for nine months, completing 36 sessions. The P4C sessions in this intervention focused on issues, such as happiness, normal vs not normal, making mistakes, sadness and anger, division and death, and family. The other group consisted of 37 children selected from the wait-list control condition. SNAP-IV and CTRS were administered as pre-and post-tests to both groups. Teachers conducted pre-intervention (a week before the intervention began) and post-intervention (a week after the intervention concluded) assessments, which included two questionnaires. The pre-test and post-test scores were compared.

Statistical analyses

Our hypotheses were investigated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), a recommended method for increasing statistical power in randomized controlled trials. Using ANCOVAs, we compared post-intervention scores between groups while adjusting for pre-intervention scores and gender. A paired t-test was used to compare pre- to post-differences within each group. The level of significance was set at P<0.05. Quantitative variables were described as Mean±SD. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 26.

Results

Effects of P4C on the SNAP-IV scores

The effectiveness of the P4C intervention in addressing symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and combined symptoms was assessed by pre- to post-test score differences using the SNAP-IV questionnaire.

The results indicated significant differences between the control and P4C groups for all three symptom domains: Inattention (F=19.972, P<0.001, ηp2=0.222), hyperactivity (F=32.505, P<0.001, ηp2=0.317), and combined symptoms (F=25.419, P<0.001, ηp2=0.266). Large effect sizes were observed, suggesting a substantial impact of P4C interventions on reducing symptoms across these domains (Table 2).

We conducted paired t-tests to assess group differences in pre- to post-intervention scores. Table 3 presents the comparison of pre- to post-test score changes between the control and P4C groups. In the control group, a slight decrease was observed in mean inattention scores from 0.98±0.78 at the pre-test to 0.85±0.59 at the post-test, although this change was not statistically significant (P=0.243). Conversely, the P4C group demonstrated a significant reduction in inattention symptoms, with mean scores decreasing from 0.75±0.51 at the pre-test to 0.44±0.45 at the post-test (P=0.008).

For hyperactivity, both the control and P4C groups exhibited minimal changes in mean scores from pre to post-test, with P of 0.957 and P<0.0001, respectively. However, the P4C group showed a significant reduction in hyperactivity symptoms compared to the control group. Similarly, for combined symptoms, the P4C intervention resulted in a significant reduction in mean scores from pre- to post-test (P<0.0001), whereas the control group showed less pronounced changes (P=0.497).

Effects of P4C on the Conner’s scale scores

Table 4 presents the results of the ANCOVA conducted to assess the intervention’s effects across various domains of CTRS. The ANCOVA results revealed substantial differences between the control and target groups across all domains of CTRS. Specifically, for hyperactivity, conduct problems, social problems, anxiety, and inattention, the F-values were 42.311, 40.220, 34.775, 32.920, and 40.525, respectively, all with P<0.001.

Furthermore, the effect sizes, measured by partial eta squared, were substantial in each domain, indicating that the intervention explained a considerable proportion of the variance in the dependent variable while controlling for covariates. Partial eta-squared values ranged from 0.320 to 0.388, suggesting strong intervention effects across the various domains of CTRS.

To assess within-group changes in pre- to-post-intervention scores, paired t-tests were applied. Table 5 presents the comparison of pre- to post-test score changes between the control and P4C groups. In the control group, a slight decrease was observed in mean hyperactivity scores from 10.4±7.38 at the pre-test to 9.64±4.87 at the post-test. However, this change was not statistically significant (P=0.345). Conversely, the P4C group demonstrated a significant reduction in hyperactivity symptoms, with mean scores decreasing from 9.48±5.72 at the pre-test to 5.05±4.27 at the post-test (P<0.0001).

For conduct problems, both the control and P4C groups exhibited changes in mean scores from pre- to post-test, with P of 0.973 and <0.0001, respectively. However, the P4C group showed a substantial reduction in conduct problems compared to the control group. Similarly, for social problems, anxiety, inattention, and total symptoms, the P4C intervention resulted in a significant reduction in mean scores from pre- to post-test (P<0.0001), whereas the control group showed less pronounced changes (P=0.649, 0.468, 0.151, 0.556, respectively).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the impact of a P4C-based program on Iranian children’s mental health. Compared to the control group, members of the target group tended to perform better in addressing mental health symptoms, including conduct problems, social problems, anxiety, inattention, and hyperactivity. In the context of our P4C program, we employed two standardized assessment tools SNAP-IV questionnaire and the CTRS scale. These instruments were selected for their ability to comprehensively evaluate behavioral and emotional aspects, including symptoms associated with ADHD in children. The SNAP-IV questionnaire is widely used to assess ADHD symptoms, such as inattention and hyperactivity, in clinical and research settings. Similarly, the CTRS provides valuable insights into various domains of behavior, including hyperactivity, conduct problems, and inattention. In our study, we observed significant reductions in inattention symptoms within the P4C group, whereas the control group did not exhibit significant changes. Although both groups showed minimal changes in hyperactivity symptoms, the P4C group demonstrated a notable decrease compared to controls. Moreover, the P4C intervention resulted in statistically significant reductions in combined symptoms compared to the control group. Additionally, post-test scores decreased significantly across all domains of the CTRS (hyperactivity, conduct problems, social problems, anxiety, and inattention) in the P4C group, while no significant differences were observed in the control group. These findings highlight the effectiveness of the P4C intervention in addressing ADHD symptoms and improving overall mental health outcomes in children.

Öner et al. (2019) evaluated ADHD symptoms, such as inattention and hyperactivity, in younger students for their grade in a low- to middle-income country using SNAP-IV scales. When age, gender, and fluid intelligence quotient (IQ) scores were considered, the results indicated that teachers assessed ADHD symptoms as 2.5–3.6 times more prevalent among students who were younger than their peers. Epstein et al. (1998) examined racial differences in CTRS scores among healthy children. This study examined potential disparities in the rating scale’s results across different racial groups and sought to understand their underlying reasons. The results showed that black females rated the conduct problems factor significantly higher than white females, and black males scored significantly higher than white male children on the conduct problems and hyperactivity factors. Notably, they suspected that this significant difference may be due to teacher bias and suggested that further investigation is necessary. The current educational crisis highlights a significant gap in students’ interpersonal connections, as education systems worldwide focus heavily on acquiring knowledge and skills for citizenship and economic contributions while often neglecting essential human aspects, such as health, happiness, and values (Ozmon & Craver, 1981). A significant challenge faced by teachers today is their inability to address the complete spectrum of students’ psychological and social requirements during classroom instruction. This is one reason why students do not feel engaged in their education and may fail to provide a means that directs and inspires their progress. Deci and Ryan (Deci & Ryan, 1990; Deci & Ryan, 2008) highlighted that intrinsic motivation includes conditions, such as autonomy, competence, and a sense of belonging or connectedness. Traditional educational settings often dismiss students’ individuality, beliefs, thoughts, interests, personal experiences, questions, and curiosity (Leng, 2020). However, the P4C approach fosters a culture of curiosity and exploration, where students’ personal experiences and questions are valued. This paradigm shift allows students to genuinely connect with their learning, as they learn to align their thoughts with evidence and reason. In these classrooms, educators are passionate about their students’ academic needs and are deeply concerned about their social, emotional, behavioral, and psychological states. Teachers aim to create a space for intrinsic motivation and self-exploration, fostering stronger connections within students and between students and teachers, ultimately leading to a more meaningful educational experience. In 2021, Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al. investigated the impact of P4C and an online mindfulness-based intervention on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic among 37 students (both girls and boys; average age: 8.18 years) (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2021). In comparison to mindfulness, P4C appeared to be more effective in reducing mental health issues, including anxiety and inattention, according to the study. In this study, we assessed the effects of P4C on mental health and found that P4C has a positive influence on improving these aspects.

Trickey and Topping examined the impact of collaborative philosophical inquiry (CPI) on students aged 11–12 over seven months (Trickey & Topping, 2006). The findings indicated that there were significant differences in self-esteem, anxiety, and dependency between the target and control groups, and girls gained more than boys; also, no substantial differences were observed in social skills between the target and control groups. However, the impact of P4C on conduct/social problems has not been adequately addressed. However, our findings revealed that P4C had a favorable impact on enhancing these characteristics.

According to the majority of studies, the duration of applied P4C programs varied widely from 5 weeks (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2021), 10 weeks (Cassidy et al., 2018), to 8 months (Säre et al., 2016). Here, we applied a 9-month study period, since the course study in Iran lasts 9 months, and the main reason was to investigate the long-term effects of the P4C method on mental health compared to control groups. However, a study revealed that the duration of the program, which exposed students for just under a year, may not have been long enough for the full impact of P4C to be felt. One study examined the cognitive effects of CPI sessions with 10–12-year-old schoolchildren in the UK for 16 months. The 60-minute sessions aimed to get the children thinking philosophically by discussing open-ended questions. The study found that these philosophy sessions had positive effects on the children’s verbal, non-verbal, and quantitative reasoning abilities. Participating in regular philosophical discussions strengthened the children’s cognitive flexibility and ability to consider multiple viewpoints in both girls and boys. It also benefited their reasoning and critical thinking capacities over time. Additionally, boys had slightly higher pre-test scores than girls on all subscales. Boys achieved greater gains than girls in overall scores and verbal and non-verbal subscale scores. Regarding the quantitative subscale scores, girls outperformed boys (Topping & Trickey, 2007a). Also, the follow-up study reassessed students two years after completing the program to determine whether any cognitive gains were maintained over time. It found that students who had participated in CPI continued to outperform controls on measures of verbal, non-verbal, and overall cognitive ability even 2 years later. The results suggested that CPI had lasting benefits for students’ cognitive development, well beyond the duration of the intervention program, and improved critical thinking skills that transfer more broadly over time (Topping & Trickey, 2007b).

Typically, ADHD symptoms begin before the age of 12, and in some children, they become noticeable as young as four years old (Doğru, 2022). Anxiety, hyperactivity, and inattention are considered to be symptoms of ADHD, and an increase in childhood and a lack of control can be a warning of a serious injury and disorder. P4C is a method that has improved obsessive-compulsive disorder (Darezereshki Poor et al., 2020) and mental health problems (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2021) (anxiety and inattention). A case study exploring the participation of a student with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in guided philosophical dialogues. By analyzing students’ involvement in structured philosophical discussions, this study sheds light on the potential benefits of this intellectual engagement for individuals with ASD, suggesting it may be a valuable approach to enhancing their cognitive development and communication (Gardelli et al., 2023). Hence, it is necessary to investigate the effects of this educational method on the domains mentioned in this study.

One of the shortcomings of our study, related to gender, was the unequal distribution of male and female participants across the control and target groups. To address this issue, we included gender as a covariate in the analysis. We recommend implementing a philosophy education program for children in gender-specific groups in future studies. Also, the balance between boys and girls should be given special attention.

There has also been a paucity of research examining the effects of philosophical educational programs on children of different ages. In a 9-month P4C program, Giménez-Dasí et al. (2013) evaluated 60, 4- to 5-year-old children to assess their social skills and emotional understanding. Furthermore, Fair et al. (2015) examined the influence of P4C training and found a significant difference in the positive effects of cognitive skills acquired between 7th- and 8th-grade primary students. Future investigations should examine the effects of P4C across different grades more precisely.

The potential impact of socioeconomic factors on children’s mental well-being (if any) remains unclear, and further investigation into the association between P4C outcomes and social factors is required. It seems P4C outcomes are affected by the combination of gender, age, and socioeconomic status (Khodagholi, 2023).

To enhance the validity of our findings from teacher-completed questionnaires, augmenting our methodology with additional neuroimaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography, can be helpful. These advanced imaging methods can offer objective measures of brain activity and connectivity associated with symptoms, providing valuable complementary insights to questionnaire-based assessments. Integrating neuroimaging data with questionnaire responses, behavioral assessments, and self-reported measures can facilitate a more holistic evaluation of children’s mental health and cognitive functioning. Further investigations with more participants, incorporating advanced imaging techniques, and covering socioeconomic status may enhance the reliability and depth of the findings.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the research Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1400.077). The participants’ legal guardians or next of kin, and the participating teachers, provided their informed consent to participate in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Neuroscience Research Center, Institute of Neuroscience and Cognition, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant No.: 29795-7-4).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Fatemeh Vosoughian, Fariba Khodagholi, and Fereshteh Khodagholi; Experimens: Fatemeh Vosoughian and Fereshteh Khodagholi; Data curation: Roohollah Karimi and Yahya Ghaedi; Data analysis: Fatemeh Vosoughian, Arman Zeinaddini-Meymand, and Saba Amiri; Data interpretation and writing the original draft: Fatemeh Vosoughian, Saba Amiri, and Fariba Khodagholi; Review and editing: Maryam Alsadat Mousavi, Taravat Rasooli, Fariba Khodagholi, and Saba Amiri; Supervison: Fariba Khodagholi and Saba Amiri.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants and their families for their participation in this study, and the teachers who contributed valuable insights and completed the questionnaires.

References

Childhood is crucial for developing social, emotional, and intellectual abilities. This is due to the high level of brain malleability during this time, which facilitates learning and adjusting to one’s surroundings (Gabard-Durnam & McLaughlin, 2020; Kolb & Gibb, 2014). Cognitive ability is the human mind’s capacity to extract, process, store, communicate, and reproduce information from the external world (Yan & Li, 2023). Cognitive ability typically includes verbal, numerical, technological proficiency, and logical reasoning skills (Hunter, 1986). Individuals with lower cognitive performance during youth have an increased likelihood of mental health problems many years later (Gale et al., 2012). Cognitive difficulties may involve problems with focus, information recall, scheduling, organizing, logical reasoning, and problem-solving. These cognitive skills are essential for numerous functional duties, such as employment, education, social interactions, community participation, and independent living (Clements & Karmas, 2015). Children and adolescents with higher intelligence test scores are generally less likely to be diagnosed with depressive or anxiety disorders or to report indications (signs) of psychological suffering later in life (Hatch et al., 2007; Koenen et al., 2009; Martin et al., 2007). These issues represent only one extreme of the broad spectrum of mental well-being. Due to the significant scientific and societal implications, the possibility of improving cognitive skills through training and interventions has been one of the most influential topics in cognitive psychology. Research has shown that digital education technology can stimulate students’ intrinsic motivation, inspire them to learn, and improve their cognitive skills (Yan & Li, 2023). Moreover, studies have explored the intricate relationship between working memory (WM) and overall cognition, suggesting that targeted WM training could lead to significant cognitive improvements across various domains (Morrison & Chein, 2011). Other interventions, such as dance (Kein et al., 2000), music (Schellenberg et al., 2007), and chess (Sala & Gobet, 2016) in addition to using media, such as pop-up book learning media (Dian Idha & Rukiyati, 2018), have been hypothesized to impact cognitive ability.

Given the undeniable shortcomings of prevalent methods, most countries seek to develop approaches that cultivate thinking, creativity, and problem-solving. Therefore, diverse educational methods have emerged, including creative thinking, critical thinking, problem-solving skills, innovative curricula, and philosophy programs for children (Hogan, 2006).

The practice of “philosophy for children” (P4C) is considered one of the initial tools for developing thinking abilities (Zulkifli & Hashim, 2020). The use of P4C is becoming increasingly widespread in school settings, particularly to promote youth well-being. Lipman is known for founding P4C in the 1970s and holds the belief that philosophical thinking can be taught at any age (Khanmohammadi et al., 2020). This educational program is designed to promote critical thinking, caring, creative reasoning, and inquiry within the educational environment (Lipman, 1985; Vansieleghem & Kennedy, 2011). Lipman explains that P4C aims to broaden the scope of philosophy by using it as a pedagogical tool. In this teaching method, philosophy is employed to stimulate children’s innate desire and interest in seeking meaning and understanding (Lipman, 2003). The educational material in programs that utilize this philosophical approach consists of philosophical stories, and the processes are focused on communities of inquiry. The term “inquiry” is chosen over “lesson” because the focus is on the group investigating questions together with the teacher acting as a facilitator rather than an authoritative source of information (Bleazby, 2013). Throughout P4C exercises, students are provided with an existential or philosophical subject when they read a story, watch a short video, or select themes (Lipman, 2010). P4C incorporates discussion as a primary element. In addition, in a community of inquiry, learners have the opportunity to deeply reflect on and assess several concepts. Class exploration circles provide an environment for learners to develop emotionally and socially in addition to their cognitive and political growth (Haynes, 2008). In these circumstances, they can have actual discussions, respect one another, build on ever-increasing sense of confidence, and increase their ability to communicate at different levels. Through P4C, children can learn to be more thoughtful, adaptable, considerate, and logical (Khanmohammadi et al., 2020).

Childhood mental health issues have significant adverse effects on individuals, families, and society (Ogundele, 2018). Consequently, it is imperative to promptly address many issues that children may encounter, including anxiety, conduct problems, and symptoms, such as hyperactivity and inattention. Various interventions have been used to mitigate the issues described above (Fisak et al., 2023; Gardner et al., 2006; Salartash et al., 2022). The current study set out to assess the effect of the P4C intervention on children’s social problems, including items, such as being unaccepted, being isolated, having no fair play, lacking leadership, having trouble with the same sex, being uncooperative and easily led, conduct problems, including items, such as being impudent, lying, being destructive, being quarrelsome, stealing, disturbing, teasing, and acting wise. Other factors include hyperactivity, anxiety, and inattention symptoms (Rezai et al., 2015).

Materials and Methods

The current study enrolled 74 Iranian children (41 boys and 33 girls) with a Mean±SD age of 8.86±2.16 years (range: 6–13 years). According to reports from teachers and parents, no clinical diagnosis of psychiatric disorders has been reported. They were then randomly categorized into two groups: Control and P4C (Table 1). The Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran, approved this study. Both the participants’ legal guardians or next of kin and the participating teachers provided informed consent to participate in the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant Helsinki guidelines and regulations.

Instruments

Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham (SNAP-IV)

The SNAP-IV is an 18-item scale (Swanson, 1992; Swanson et al., 1983) and that is commonly used to evaluate the main symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Hall et al., 2019) in both ADHD (Luo et al., 2022) and healthy communities (Öner et al., 2019). This questionnaire uses a 4-point Likert scale from not at all (0) to very much (3) to assess the following factors: Hyperactivity/impulsivity (9 items), inattention (9 items), and combined (both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive) (18 items). SNAP has high reliability and validity (Bussing et al., 2008). The questionnaire has been modified for Iranian society (Sadr Alsadat et al., 2009). Sadr-Alsadat reported a test re-test reliability of 82% for the teacher form, with Cronbach’s α coefficients at 90% (Sadr alsadat et al., 2008).

Connors teacher rating scale (CTRS)

The CTRS, originally developed in 1968 with 39 items (Conners, 1969), remains a valuable and accurate tool for evaluating behavioral issues in children and teenagers. This multiple-choice questionnaire uses a Likert scale, with possible answers ranging from 0 (never or very rarely) to 3 (always or most of the time). This questionnaire has been adjusted for Iranian society (Rezai et al., 2015). Connors (1969) reported that the test re-test reliability of the teacher form ranged from 72% to 92% over a month to a year, and that 70% of the teachers’ scoring reliability was also reported. The cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 61% to 95% (Shahim et al., 2008).

Procedure

The participants were randomly categorized into two groups. The intervention group comprised 37 children who participated in weekly 1-hour P4C sessions for nine months, completing 36 sessions. The P4C sessions in this intervention focused on issues, such as happiness, normal vs not normal, making mistakes, sadness and anger, division and death, and family. The other group consisted of 37 children selected from the wait-list control condition. SNAP-IV and CTRS were administered as pre-and post-tests to both groups. Teachers conducted pre-intervention (a week before the intervention began) and post-intervention (a week after the intervention concluded) assessments, which included two questionnaires. The pre-test and post-test scores were compared.

Statistical analyses

Our hypotheses were investigated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), a recommended method for increasing statistical power in randomized controlled trials. Using ANCOVAs, we compared post-intervention scores between groups while adjusting for pre-intervention scores and gender. A paired t-test was used to compare pre- to post-differences within each group. The level of significance was set at P<0.05. Quantitative variables were described as Mean±SD. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 26.

Results

Effects of P4C on the SNAP-IV scores

The effectiveness of the P4C intervention in addressing symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and combined symptoms was assessed by pre- to post-test score differences using the SNAP-IV questionnaire.

The results indicated significant differences between the control and P4C groups for all three symptom domains: Inattention (F=19.972, P<0.001, ηp2=0.222), hyperactivity (F=32.505, P<0.001, ηp2=0.317), and combined symptoms (F=25.419, P<0.001, ηp2=0.266). Large effect sizes were observed, suggesting a substantial impact of P4C interventions on reducing symptoms across these domains (Table 2).

We conducted paired t-tests to assess group differences in pre- to post-intervention scores. Table 3 presents the comparison of pre- to post-test score changes between the control and P4C groups. In the control group, a slight decrease was observed in mean inattention scores from 0.98±0.78 at the pre-test to 0.85±0.59 at the post-test, although this change was not statistically significant (P=0.243). Conversely, the P4C group demonstrated a significant reduction in inattention symptoms, with mean scores decreasing from 0.75±0.51 at the pre-test to 0.44±0.45 at the post-test (P=0.008).

For hyperactivity, both the control and P4C groups exhibited minimal changes in mean scores from pre to post-test, with P of 0.957 and P<0.0001, respectively. However, the P4C group showed a significant reduction in hyperactivity symptoms compared to the control group. Similarly, for combined symptoms, the P4C intervention resulted in a significant reduction in mean scores from pre- to post-test (P<0.0001), whereas the control group showed less pronounced changes (P=0.497).

Effects of P4C on the Conner’s scale scores

Table 4 presents the results of the ANCOVA conducted to assess the intervention’s effects across various domains of CTRS. The ANCOVA results revealed substantial differences between the control and target groups across all domains of CTRS. Specifically, for hyperactivity, conduct problems, social problems, anxiety, and inattention, the F-values were 42.311, 40.220, 34.775, 32.920, and 40.525, respectively, all with P<0.001.

Furthermore, the effect sizes, measured by partial eta squared, were substantial in each domain, indicating that the intervention explained a considerable proportion of the variance in the dependent variable while controlling for covariates. Partial eta-squared values ranged from 0.320 to 0.388, suggesting strong intervention effects across the various domains of CTRS.

To assess within-group changes in pre- to-post-intervention scores, paired t-tests were applied. Table 5 presents the comparison of pre- to post-test score changes between the control and P4C groups. In the control group, a slight decrease was observed in mean hyperactivity scores from 10.4±7.38 at the pre-test to 9.64±4.87 at the post-test. However, this change was not statistically significant (P=0.345). Conversely, the P4C group demonstrated a significant reduction in hyperactivity symptoms, with mean scores decreasing from 9.48±5.72 at the pre-test to 5.05±4.27 at the post-test (P<0.0001).

For conduct problems, both the control and P4C groups exhibited changes in mean scores from pre- to post-test, with P of 0.973 and <0.0001, respectively. However, the P4C group showed a substantial reduction in conduct problems compared to the control group. Similarly, for social problems, anxiety, inattention, and total symptoms, the P4C intervention resulted in a significant reduction in mean scores from pre- to post-test (P<0.0001), whereas the control group showed less pronounced changes (P=0.649, 0.468, 0.151, 0.556, respectively).

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the impact of a P4C-based program on Iranian children’s mental health. Compared to the control group, members of the target group tended to perform better in addressing mental health symptoms, including conduct problems, social problems, anxiety, inattention, and hyperactivity. In the context of our P4C program, we employed two standardized assessment tools SNAP-IV questionnaire and the CTRS scale. These instruments were selected for their ability to comprehensively evaluate behavioral and emotional aspects, including symptoms associated with ADHD in children. The SNAP-IV questionnaire is widely used to assess ADHD symptoms, such as inattention and hyperactivity, in clinical and research settings. Similarly, the CTRS provides valuable insights into various domains of behavior, including hyperactivity, conduct problems, and inattention. In our study, we observed significant reductions in inattention symptoms within the P4C group, whereas the control group did not exhibit significant changes. Although both groups showed minimal changes in hyperactivity symptoms, the P4C group demonstrated a notable decrease compared to controls. Moreover, the P4C intervention resulted in statistically significant reductions in combined symptoms compared to the control group. Additionally, post-test scores decreased significantly across all domains of the CTRS (hyperactivity, conduct problems, social problems, anxiety, and inattention) in the P4C group, while no significant differences were observed in the control group. These findings highlight the effectiveness of the P4C intervention in addressing ADHD symptoms and improving overall mental health outcomes in children.

Öner et al. (2019) evaluated ADHD symptoms, such as inattention and hyperactivity, in younger students for their grade in a low- to middle-income country using SNAP-IV scales. When age, gender, and fluid intelligence quotient (IQ) scores were considered, the results indicated that teachers assessed ADHD symptoms as 2.5–3.6 times more prevalent among students who were younger than their peers. Epstein et al. (1998) examined racial differences in CTRS scores among healthy children. This study examined potential disparities in the rating scale’s results across different racial groups and sought to understand their underlying reasons. The results showed that black females rated the conduct problems factor significantly higher than white females, and black males scored significantly higher than white male children on the conduct problems and hyperactivity factors. Notably, they suspected that this significant difference may be due to teacher bias and suggested that further investigation is necessary. The current educational crisis highlights a significant gap in students’ interpersonal connections, as education systems worldwide focus heavily on acquiring knowledge and skills for citizenship and economic contributions while often neglecting essential human aspects, such as health, happiness, and values (Ozmon & Craver, 1981). A significant challenge faced by teachers today is their inability to address the complete spectrum of students’ psychological and social requirements during classroom instruction. This is one reason why students do not feel engaged in their education and may fail to provide a means that directs and inspires their progress. Deci and Ryan (Deci & Ryan, 1990; Deci & Ryan, 2008) highlighted that intrinsic motivation includes conditions, such as autonomy, competence, and a sense of belonging or connectedness. Traditional educational settings often dismiss students’ individuality, beliefs, thoughts, interests, personal experiences, questions, and curiosity (Leng, 2020). However, the P4C approach fosters a culture of curiosity and exploration, where students’ personal experiences and questions are valued. This paradigm shift allows students to genuinely connect with their learning, as they learn to align their thoughts with evidence and reason. In these classrooms, educators are passionate about their students’ academic needs and are deeply concerned about their social, emotional, behavioral, and psychological states. Teachers aim to create a space for intrinsic motivation and self-exploration, fostering stronger connections within students and between students and teachers, ultimately leading to a more meaningful educational experience. In 2021, Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al. investigated the impact of P4C and an online mindfulness-based intervention on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic among 37 students (both girls and boys; average age: 8.18 years) (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2021). In comparison to mindfulness, P4C appeared to be more effective in reducing mental health issues, including anxiety and inattention, according to the study. In this study, we assessed the effects of P4C on mental health and found that P4C has a positive influence on improving these aspects.

Trickey and Topping examined the impact of collaborative philosophical inquiry (CPI) on students aged 11–12 over seven months (Trickey & Topping, 2006). The findings indicated that there were significant differences in self-esteem, anxiety, and dependency between the target and control groups, and girls gained more than boys; also, no substantial differences were observed in social skills between the target and control groups. However, the impact of P4C on conduct/social problems has not been adequately addressed. However, our findings revealed that P4C had a favorable impact on enhancing these characteristics.

According to the majority of studies, the duration of applied P4C programs varied widely from 5 weeks (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2021), 10 weeks (Cassidy et al., 2018), to 8 months (Säre et al., 2016). Here, we applied a 9-month study period, since the course study in Iran lasts 9 months, and the main reason was to investigate the long-term effects of the P4C method on mental health compared to control groups. However, a study revealed that the duration of the program, which exposed students for just under a year, may not have been long enough for the full impact of P4C to be felt. One study examined the cognitive effects of CPI sessions with 10–12-year-old schoolchildren in the UK for 16 months. The 60-minute sessions aimed to get the children thinking philosophically by discussing open-ended questions. The study found that these philosophy sessions had positive effects on the children’s verbal, non-verbal, and quantitative reasoning abilities. Participating in regular philosophical discussions strengthened the children’s cognitive flexibility and ability to consider multiple viewpoints in both girls and boys. It also benefited their reasoning and critical thinking capacities over time. Additionally, boys had slightly higher pre-test scores than girls on all subscales. Boys achieved greater gains than girls in overall scores and verbal and non-verbal subscale scores. Regarding the quantitative subscale scores, girls outperformed boys (Topping & Trickey, 2007a). Also, the follow-up study reassessed students two years after completing the program to determine whether any cognitive gains were maintained over time. It found that students who had participated in CPI continued to outperform controls on measures of verbal, non-verbal, and overall cognitive ability even 2 years later. The results suggested that CPI had lasting benefits for students’ cognitive development, well beyond the duration of the intervention program, and improved critical thinking skills that transfer more broadly over time (Topping & Trickey, 2007b).

Typically, ADHD symptoms begin before the age of 12, and in some children, they become noticeable as young as four years old (Doğru, 2022). Anxiety, hyperactivity, and inattention are considered to be symptoms of ADHD, and an increase in childhood and a lack of control can be a warning of a serious injury and disorder. P4C is a method that has improved obsessive-compulsive disorder (Darezereshki Poor et al., 2020) and mental health problems (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2021) (anxiety and inattention). A case study exploring the participation of a student with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in guided philosophical dialogues. By analyzing students’ involvement in structured philosophical discussions, this study sheds light on the potential benefits of this intellectual engagement for individuals with ASD, suggesting it may be a valuable approach to enhancing their cognitive development and communication (Gardelli et al., 2023). Hence, it is necessary to investigate the effects of this educational method on the domains mentioned in this study.

One of the shortcomings of our study, related to gender, was the unequal distribution of male and female participants across the control and target groups. To address this issue, we included gender as a covariate in the analysis. We recommend implementing a philosophy education program for children in gender-specific groups in future studies. Also, the balance between boys and girls should be given special attention.

There has also been a paucity of research examining the effects of philosophical educational programs on children of different ages. In a 9-month P4C program, Giménez-Dasí et al. (2013) evaluated 60, 4- to 5-year-old children to assess their social skills and emotional understanding. Furthermore, Fair et al. (2015) examined the influence of P4C training and found a significant difference in the positive effects of cognitive skills acquired between 7th- and 8th-grade primary students. Future investigations should examine the effects of P4C across different grades more precisely.

The potential impact of socioeconomic factors on children’s mental well-being (if any) remains unclear, and further investigation into the association between P4C outcomes and social factors is required. It seems P4C outcomes are affected by the combination of gender, age, and socioeconomic status (Khodagholi, 2023).

To enhance the validity of our findings from teacher-completed questionnaires, augmenting our methodology with additional neuroimaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography, can be helpful. These advanced imaging methods can offer objective measures of brain activity and connectivity associated with symptoms, providing valuable complementary insights to questionnaire-based assessments. Integrating neuroimaging data with questionnaire responses, behavioral assessments, and self-reported measures can facilitate a more holistic evaluation of children’s mental health and cognitive functioning. Further investigations with more participants, incorporating advanced imaging techniques, and covering socioeconomic status may enhance the reliability and depth of the findings.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the research Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.PHNS.REC.1400.077). The participants’ legal guardians or next of kin, and the participating teachers, provided their informed consent to participate in the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Neuroscience Research Center, Institute of Neuroscience and Cognition, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant No.: 29795-7-4).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and study design: Fatemeh Vosoughian, Fariba Khodagholi, and Fereshteh Khodagholi; Experimens: Fatemeh Vosoughian and Fereshteh Khodagholi; Data curation: Roohollah Karimi and Yahya Ghaedi; Data analysis: Fatemeh Vosoughian, Arman Zeinaddini-Meymand, and Saba Amiri; Data interpretation and writing the original draft: Fatemeh Vosoughian, Saba Amiri, and Fariba Khodagholi; Review and editing: Maryam Alsadat Mousavi, Taravat Rasooli, Fariba Khodagholi, and Saba Amiri; Supervison: Fariba Khodagholi and Saba Amiri.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants and their families for their participation in this study, and the teachers who contributed valuable insights and completed the questionnaires.

References

Bleazby, J. (2013). Social reconstruction learning: Dualism, dewey and philosophy in schools. New York: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780203069110]

Bussing, R., Fernandez, M., Harwood, M., Wei Hou, Garvan, C. W., & Eyberg, S. M., et al. (2008). Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: Psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment, 15(3), 317–328.[DOI:10.1177/1073191107313888] [PMID]

Cassidy, C., Marwick, H., Deeney, L., & McLean, G. (2018). Philosophy with children, self-regulation and engaged participation for children with emotional-behavioural and social communication needs. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 23(1), 81-96. [DOI:10.1080/13632752.2017.1388654]

Conners, C. K. (1969). A teacher rating scale for use in drug studies with children. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 126(6), 884–888. [DOI:10.1176/ajp.126.6.884] [PMID]

Darezereshki Poor, O., Fallh, M. H., & Saeidmanesh, M. (2020). [Designing stories to create cognitive faults in the philosophy program for children and its effectiveness on reducing the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children with OCD symptoms in the elementary school of Yazd city (Persian)]. Thinking and Children, 10(2), 69-90. [Link]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 38:237-88, 38, 237-288. [PMID]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182. [DOI:10.1037/a0012801]

Dian Idha, R., & Rukiyati, R. (2018). Developing pop-up book learning media to improve cognitive ability of children aged 4-5 years. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Early Childhood Education. Semarang Early Childhood Research and Education Talks, 249, 60-69. [DOI:10.2991/secret-18.2018.10]

Doğru, H. (2022). Is occupational therapy beneficial for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder accompanying agenesis of the corpus callosum? The Turkish Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 29(2), 127-129. [DOI:10.4274/tjcamh.galenos.2020.09719]

Epstein, J. N., March, J. S., Conners, C. K., & Jackson, D. L. (1998). Racial differences on the Conners teacher rating scale. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26(2), 109-118. [DOI:10.1023/A:1022617821422] [PMID]

Fair, F., Haas, L., Gardosik, C., Johnson, D., Price, D., & Leipnik, O. (2015). Socrates in the schools from Scotland to Texas: Replicating a study on the effects of a Philosophy for Children program. Journal of Philosophy in Schools, 2, 18-37. [DOI:10.21913/JPS.v2i1.1100]

Khodagholi, F., Mousavi, M. A., Ghaedi, Y., Salarvandian, S., Vosoughian, F., & Javadi, M, et al. (2025). Looking at philosophy for children and its outcomes through a neuroscience lens. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 16 (3), 551-568. [DOI:10.32598/bcn.2024.6110.1]

Fisak, B., Penna, A., Mian, N. D., Lamoli, L., Margaris, A., & Cruz, S. A. M. F. D. (2023). The effectiveness of anxiety interventions for young children: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(8), 2546-2557. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-023-02596-y] [PMID]

Gabard-Durnam, L., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2020). Sensitive periods in human development: Charting a course for the future. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 36, 120-128. [DOI:10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.09.003]

Gale, C. R., Cooper, R., Craig, L., Elliott, J., Kuh, D., & Richards, M., et al. (2012). Cognitive function in childhood and lifetime cognitive change in relation to mental wellbeing in four cohorts of older people. Plos One, 7(9), e44860. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0044860] [PMID]

Gardelli, V., Backman, Y., Gardelli, Å., & Franklin, A. (2023). ‘You talk and try to think, together’ - a case study of a student diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder participating in philosophical dialogues. Childhood and Philosophy, 19, 1-28. [DOI:10.12957/childphilo.2023.70493]

Gardner, F., Burton, J., & Klimes, I. (2006). Randomised controlled trial of a parenting intervention in the voluntary sector for reducing child conduct problems: Outcomes and mechanisms of change. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47(11), 1123–1132. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01668.x] [PMID]

Giménez-Dasí, M., Quintanilla, L., & Daniel, M. F. (2013). Improving emotion comprehension and social skills in early childhood through philosophy for children. Childhood & Philosophy, 9(17), 63-89. [Link]

Hall, C. L., Guo, B., Valentine, A. Z., Groom, M. J., Daley, D., & Sayal, K., et al. (2020). The validity of the SNAP-IV in children displaying ADHD symptoms. Assessment, 27(6), 1258-1271. [DOI:10.1177/1073191119842255] [PMID]

Hatch, S. L., Jones, P. B., Kuh, D., Hardy, R., Wadsworth, M. E., & Richards, M. (2007). Childhood cognitive ability and adult mental health in the British 1946 birth cohort. Social Science & Medicine, 64(11), 2285-2296. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.027] [PMID]

Haynes, J. (2008). Children as Philosophers: Learning Through Enquiry and Dialogue in the Primary Classroom. London: Routledge. [DOI:10.4324/9780203927595]

Henderson, C., Clements, S. C., S Humin, Y & Karmas, R. 2015. Cognitive functioning: Supporting people with mental health conditions. Lilyfield: Mental Health Coordinating Council Inc. (MHCC). [Link]

Hogan, M. (2006). Cultivating thought-full and creative thinkers: A comment on quality merging Costa with Claxton et al. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 1(2), 152-154. [DOI:10.1016/j.tsc.2006.05.001]

Hunter, J. E. (1986). Cognitive ability, cognitive aptitudes, job knowledge, and job performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 29(3), 340-362. [DOI:10.1016/0001-8791(86)90013-8]

Kein, M., Hetland, L., & Winner, E. (2000). Teaching cognitive skill through dance: Evidence for near but not far transfer. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 34(3/4), 295-306. [DOI:10.2307/3333646]

Khanmohammadi, M., Seifi, M., & Nateghi, F. (2020). Effectiveness of applying philosophy for children (P4C) teaching approach in a media literacy course. Interdisciplinary Journal of Virtual Learning in Medical Sciences, 11(2), 112-120. [DOI:10.30476/ijvlms.2020.86041.1032]

Koenen, K. C., Moffitt, T. E., Roberts, A. L., Martin, L. T., Kubzansky, L., & Harrington, H., et al. (2009). Childhood IQ and adult mental disorders: A test of the cognitive reserve hypothesis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(1), 50–57.[DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030343] [PMID]

Kolb, B., & Gibb, R. (2014). Searching for the principles of brain plasticity and behavior. Cortex, 58, 251-260. [DOI:10.1016/j.cortex.2013.11.012] [PMID]

Leng, L. (2020). The role of philosophical inquiry in helping students engage in learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 449.[DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00449] [PMID]

lipman, M. (2003). Thinking in education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Link]

Lipman, M., Sharp, A. M., & Oscanyan, F. S. (2010). Philosophy in the classroom. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. [Link]

Lipman, M. Philosophy for children. (1985). In: Costa, A.L., (Ed), Developing minds: A resource book for teaching thinking. Arlington: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [Link]

Luo, J., Huang, H., Wang, S., Yin, S., Chen, S., & Guan, L., et al. (2022). A wearable diagnostic assessment system vs. SNAP-IV for the auxiliary diagnosis of ADHD: A diagnostic test. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 415. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-022-04038-3] [PMID]

Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Di Tomaso, C., Lefrançois, D., Mageau, G. A., Taylor, G., & Éthier, M. A., et al. (2021). Existential therapy for children: Impact of a philosophy for children intervention on positive and negative indicators of mental health in elementary school children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12332. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph182312332] [PMID]

Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Léger-Goodes, T., Mageau, G. A., Joussemet, M., Herba, C., & Chadi, N., et al. (2021). Philosophy for children and mindfulness during COVID-19: Results from a randomized cluster trial and impact on mental health in elementary school students. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 107, 110260. [DOI:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110260] [PMID]

Martin, L. T., Kubzansky, L. D., LeWinn, K. Z., Lipsitt, L. P., Satz, P., & Buka, S. L. (2007). Childhood cognitive performance and risk of generalized anxiety disorder. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(4), 769-775. [DOI:10.1093/ije/dym063] [PMID]

Morrison, A. B., & Chein, J. M. (2011). Does working memory training work? The promise and challenges of enhancing cognition by training working memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18(1), 46–60. [DOI:10.3758/s13423-010-0034-0] [PMID]

Ogundele, M. O. (2018). Behavioural and emotional disorders in childhood: A brief overview for paediatricians. World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, 7(1), 9–26 [DOI:10.5409/wjcp.v7.i1.9] [PMID]

Öner, Ö., Vatanartıran, S., & Karadeniz, Ş. (2019). Grade effects on teacher ratings of ADHD symptoms among primary school students. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 60(4), 304-308. [DOI:10.1111/sjop.12540] [PMID]

Ozmon, H., & Craver, S. M. (1981). Philosophical foundations of education. New York: Merrill. [Link]

Rezai, M., Mirlu, M., & Nazari, M. (2015). [Analysis of exploratory factors and validity of Conners grading scale - teacher form in primary school students of Zanjan (Persian)]. Journal of New Thoughts on Education, 11(1), 39-55. [Link]

Sadr Alsadat S. J., Houshyari, Z., Zamani, R., & Sadr alsadat, L. (2008). [Determining the psychometric characteristics of the parental implementation snap-IV grading scale (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation, 26, 59-65. [Link]

Sadr Alsadat S. J., Houshyari, Z., Sadr Alsadat, L., Rouzbahani, A., Ghias, M., & Nikfarjam, M. (2009). [A rating scale to differentiate between conduct disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Isfahan Medical School, 27(100), 589-599. [Link]

Sala, G., & Gobet, F. (2016). Do the benefits of chess instruction transfer to academic and cognitive skills? A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 18, 46-57. [DOI:10.1016/j.edurev.2016.02.002]

Salartash, V., Yekta, M., & Zabihi, R. (2022). The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy on anxiety, physical symptoms, worry, and attention deficit in women with generalized anxiety disorder. The Open Public Health Journal, 15. [DOI:10.2174/18749445-v15-e2209080]

Säre, E., Luik, P., & Tulviste, T. (2016). Improving pre-schoolers’ reasoning skills using the philosophy for children programme. Trames-journal of The Humanities and Social Sciences, 20, 273-295. [DOI:10.3176/tr.2016.3.03]

Schellenberg, E. G., Nakata, T., Hunter, P. G., & Tamoto, S. (2007). Exposure to music and cognitive performance: Tests of children and adults. Psychology of Music, 35(1), 5-19. [DOI:10.1177/0305735607068885]

Shahim, S., Yousofi, F., & Shahaian, A. (2008). [Validity and psychometric properties of Conners rating scale - teacher form(Persian)]. Journal of Educational Sciences, 79, 1-26. [Link]

Swanson, J. M. (1992). School-based assessments and interventions for ADD students. Suffolk: K.C. Publishing. [Link]

Swanson, J. M., Sandman, C. A., Deutsch, C., & Baren, M. (1983). Methylphenidate hydrochloride given with or before breakfast: I. Behavioral, cognitive, and electrophysiologic effects. Pediatrics, 72(1), 49-55. [PMID]

Topping, K. J., & Trickey, S. (2007). Collaborative philosophical enquiry for school children: Cognitive effects at 10-12 years. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(Pt 2), 271–288.[DOI:10.1348/000709906X105328] [PMID]

Topping, K. J., & Trickey, S. (2007). Collaborative philosophical inquiry for schoolchildren: Cognitive gains at 2-year follow-up. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(Pt 4), 787–796. [DOI:10.1348/000709907x193032] [PMID]

Trickey, S., & Topping, K. J. (2006). Collaborative philosophical enquiry for school children: Socio-emotional effects at 11 to 12 years. School Psychology International, 27(5), 599-614. [DOI:10.1177/0143034306073417]

Vansieleghem, N., & Kennedy, D. (2011). What is philosophy for children, what is philosophy with children-after Matthew Lipman? Journal of Philosophy of Education, 45(2), 171-182. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9752.2011.00801.x]

Yan, D., & Li, G. (2023). A heterogeneity study on the effect of digital education technology on the sustainability of cognitive ability for middle school students. Sustainability, 15(3), 2784. [DOI:10.3390/su15032784]

Zulkifli, H., & Hashim, R. (2020). Philosophy for children (P4C) in improving critical thinking in a secondary moral education class. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 19, 29-45. [DOI:10.26803/ijlter.19.2.3]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Cognitive Neuroscience

Received: 2025/03/3 | Accepted: 2025/07/1 | Published: 2025/11/28

Received: 2025/03/3 | Accepted: 2025/07/1 | Published: 2025/11/28

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |