Volume 16, Issue 2 (March & April 2025)

BCN 2025, 16(2): 417-428 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Dalili N, Motevaseli E, Tehrani-Doost M, Zarrindast M R, Dousti Kataj P, Vousooghi N. Examining Quality of Life, Mental Health, and Craving in Opioid Users, Methadone Patients, and NA Members. BCN 2025; 16 (2) :417-428

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2801-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2801-en.html

Narges Dalili1

, Elahe Motevaseli2

, Elahe Motevaseli2

, Mehdi Tehrani-Doost3

, Mehdi Tehrani-Doost3

, Mohammad Reza Zarrindast1

, Mohammad Reza Zarrindast1

, Parviz Dousti Kataj1

, Parviz Dousti Kataj1

, Nasim Vousooghi *4

, Nasim Vousooghi *4

, Elahe Motevaseli2

, Elahe Motevaseli2

, Mehdi Tehrani-Doost3

, Mehdi Tehrani-Doost3

, Mohammad Reza Zarrindast1

, Mohammad Reza Zarrindast1

, Parviz Dousti Kataj1

, Parviz Dousti Kataj1

, Nasim Vousooghi *4

, Nasim Vousooghi *4

1- Department of Neuroscience and Addiction Studies, School of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Molecular Medicine, School of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Roozbeh Psychiatry Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Research Center for Cognitive and BeIranian National Center for Addiction Studies, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Research Center for Cognitive and Behavioral Sciences, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Department of Applied Cell Sciences, School of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Molecular Medicine, School of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Roozbeh Psychiatry Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Research Center for Cognitive and BeIranian National Center for Addiction Studies, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Research Center for Cognitive and Behavioral Sciences, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Department of Applied Cell Sciences, School of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Opioid use disorder (OUD), Methadone maintenance therapy (MMT), Narcotics anonymous (NA) group therapy, The desire for drug questionnaire (DDQ), The World Health Organization QoL-BREF (WHOQoL-BREF), The depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21)

Full-Text [PDF 620 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

1. Introduction

Substance use disorder (SUD) is a chronic and recurring condition characterized by obsessive substance seeking and use regardless of the adverse effects (Hser & Anglin, 2011). It is a complicated and difficult problem that impacts individuals, families, and communities worldwide (White & McLellan, 2008). Opioid use disorder (OUD), in particular, has become a major public health concern in recent years, as the rates of abuse and overdose deaths are rising at an alarming figure (Blendon & Benson, 2018). OUD was predicted to affect 26.8 million people worldwide in 2016, and over 100000 people die from opioid overdoses each year, including over 47000 Americans in 2017 (Strang et al., 2020).

OUD is associated with a range of physical health consequences, including respiratory depression, constipation, and an increased risk of infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C (Altice et al., 2010; Dydyk et al., 2022). In addition to the physical health complications, individuals with OUD may encounter various psychological and social challenges that can significantly impact their quality of life (QoL) (Volkow & Blanco, 2021). For example, OUD can result in mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, as well as social isolation, relationship problems, financial difficulties, and legal issues (Colasanti et al., 2011; Emery & Akil, 2020; Nunes et al., 1994; Volkow & Blanco, 2021). QoL is a multidimensional construct encompassing physical, psychological, social, and environmental elements contributing to an individual’s overall well-being (Power et al., 1999). In the context of OUD, QoL may be adversely impacted by a range of factors, including chronic pain, impaired functioning, financial difficulties, and social stigma (Hagemeier, 2018). Besides, a person’s QoL can be greatly impacted by typical mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and stress, which are also experienced often by people involved with OUD.

Opioid craving is a fundamental feature of OUD and is defined as an intense urge or desire to use drugs (Sayette, 2016). The desire can be so strong that it can overcome a person’s willingness to regulate his/her drug use, ultimately resulting in a relapse (Witkiewitz & Bowen, 2010). Craving is considered one of the major barriers to long-term recovery from OUD (Sayette, 2016) and can be caused by both physiological and psychological factors. Physiologically, it is related to changes in brain function and the release of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, which are associated with reward and pleasure (Wise & Robble, 2020). Psychologically, it can be triggered by a range of external and internal cues, such as stress, negative emotions, physical withdrawal symptoms, and drug-related environments or stimuli (Suzuki et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Understanding the factors that contribute to substance craving can help individuals and healthcare providers develop effective treatment plans to overcome SUD. The psychological component of craving can be related to the individual’s thoughts, emotions, and memories related to drug use (Brewer et al., 2013). Therefore, effective addiction treatment should address both the physiological and psychological aspects of substance craving to help people manage their urges and achieve and maintain recovery.

Several treatment approaches, such as medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and support groups like narcotics anonymous (NA), are available for patients involved with OUD (Carroll & Onken, 2005; Davis et al., 2005). In MAT, medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone are used to manage withdrawal symptoms and diminish craving (Alderks, 2017). Supportive groups such as NA provide a beneficial community for individuals in recovery and can help to reduce social isolation and stigma of OUD and improve the patient’s QoL without using replacement medications (Anderson & Ripullo, 1996).

Much research has been conducted to find out which treatment of OUD could better overcome mental health issues like depression, anxiety, and stress in patients. In addition, the superiority of different treatment methods regarding the dimensions of QoL and substance craving is an important question raised by healthcare providers. The current study was designed to investigate such questions by comparing OUD, methadone-maintenance therapy (MMT), and NA groups with control subjects regarding the scales of mental health issues, QoL, and substance craving.

2. Materials and Methods

Study participants

This cross-sectional study was performed in 2020 and included 80 male participants between the ages of 20 and 45, with 20 participants in each of the following four groups: 1) Subjects with OUD, 2) NA members previously involved with OUD who were drug-free for at least one year at the time of enrollment in the study, 3) Individuals receiving methadone maintenance treatment previously suffering from OUD who were consuming methadone for at least six months, and 4) Control people without a history of OUD. MMT clinics and NA communities in Tehran City were used to recruit participants for the first three groups. Control subjects were selected from students and staff of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The sample size was determined using power analysis, which was based on the effect size of previous studies that examined the same or similar variables, with a power of 0.80 and an alpha level of 0.05. The inclusion criteria of the study were male individuals aged 20 to 45 years, opioid addiction or NA membership or methadone use (for the corresponding groups), and no history of substance use disorder (for the control group). The exclusion criteria were having a history of psychotic disorder or severe mental illness and being currently in an acute phase of withdrawal.

All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in the study. The Ethics Committee approved the protocols and processes for human studies at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Study measures

QoL

QoL was measured using the World Health Organization (WHO) QoL-BREF (WHOQoL-BREF) scale, which was also validated in Irani-an subjects (Usefy et al., 2010).

The WHO defines QoL as a person’s perception of their place in life concerning their goals, aspirations, standards, and concerns in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live (Dimitrova, 2005). These qualities are classified into physical health, mental health, social relationships, and environmental health. The questions are ranked on a Likert scale, with items scoring between 1 and 5. The WHOQoL-BREF has been found to have good internal consistency, with Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.66 to 0.82 across different domains and cultures. The test re-test reliability of the tool is high, with intra-class correla-tion coefficients ranging from 0.70 to 0.90 (Skevington et al., 2004). A study to examine the Persian version of the questionnaire in Iran found that the WHOQoL-BREF scale had good reliability, with Cronbach α values ranging from 0.76 to 0.82 for the domains measured. In addi-tion, the intra-class correlation exceeded 0.7 for all domains (Usefy et al., 2010).

Depression, anxiety, and stress

Depression, anxiety, and stress were measured using the depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), which is a widely used tool for measuring symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. It consists of 21 items, 7 for each domain (Oei et al., 2013). The DASS-21 has shown good reliability and validity in numerous studies. Internal consistency is high for all three domains, with Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.78 to 0.97 (Henry & Crawford, 2005). Also, in the Persian version, the DASS-21 was found to have good reliability and validity. Internal consistency for all three domains is high, and Cronbach's α coefficients range from 0.82 to 0.95 (Asghari et al., 2008; Kakemam et al., 2022).

The desire for drug

The desire for drug questionnaire (DDQ) (Persian version) includes 13 questions that measure three main components of drug craving, desire and intention to use (7 questions), negative reinforcement (4 questions), and control (2 questions). One question was added to enhance the internal consistency of the harmful reinforcement component. The questionnaire uses a seven-point Likert scale to rate the intensity of feelings or thoughts related to drug use, ranging from “not at all” to “approximately complete.”

The internal consistency of the measured variables was high for the first two factors, with coefficients of 0.89 and 0.79. However, the third factor had a low internal consistency with a coefficient of 0.4. in the Persian version (Hassani-Abharian et al., 2016).

Study procedure

WHOQoL-BREF, DASS, and DDQ scales were completed face-to-face at a clinic. The questionnaires were filled in by a trained research assistant who was available to answer any query raised by the participants. The completion of the scales took approximately 30-45 min. Ethical considerations were taken into account in this study, including protecting participants’ privacy and confidentiality and minimizing potential inconveniences for participants.

Data analysis

The data obtained from the scales were analyzed using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to examine differences between the four groups on the dependent variables. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 21, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

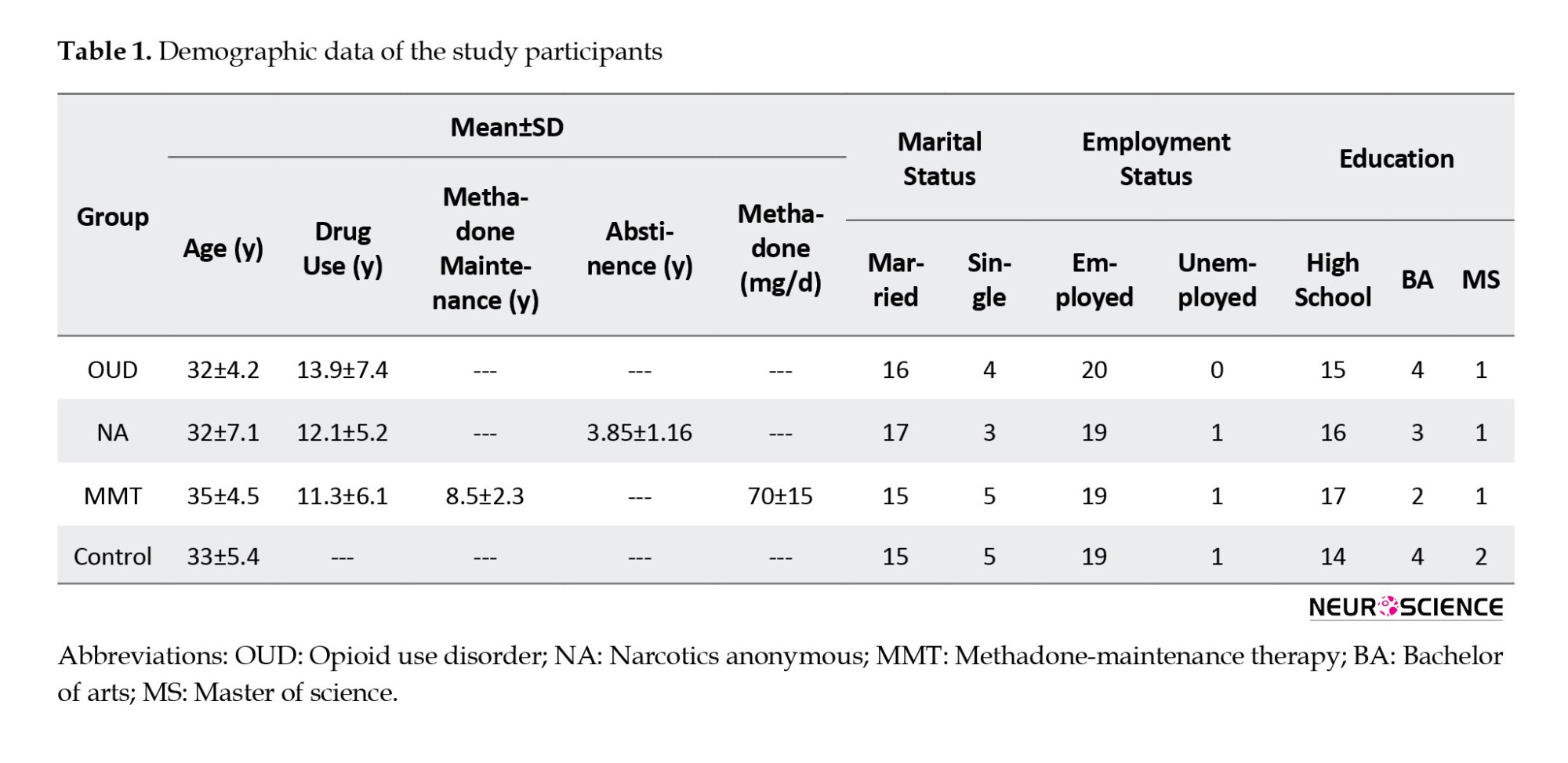

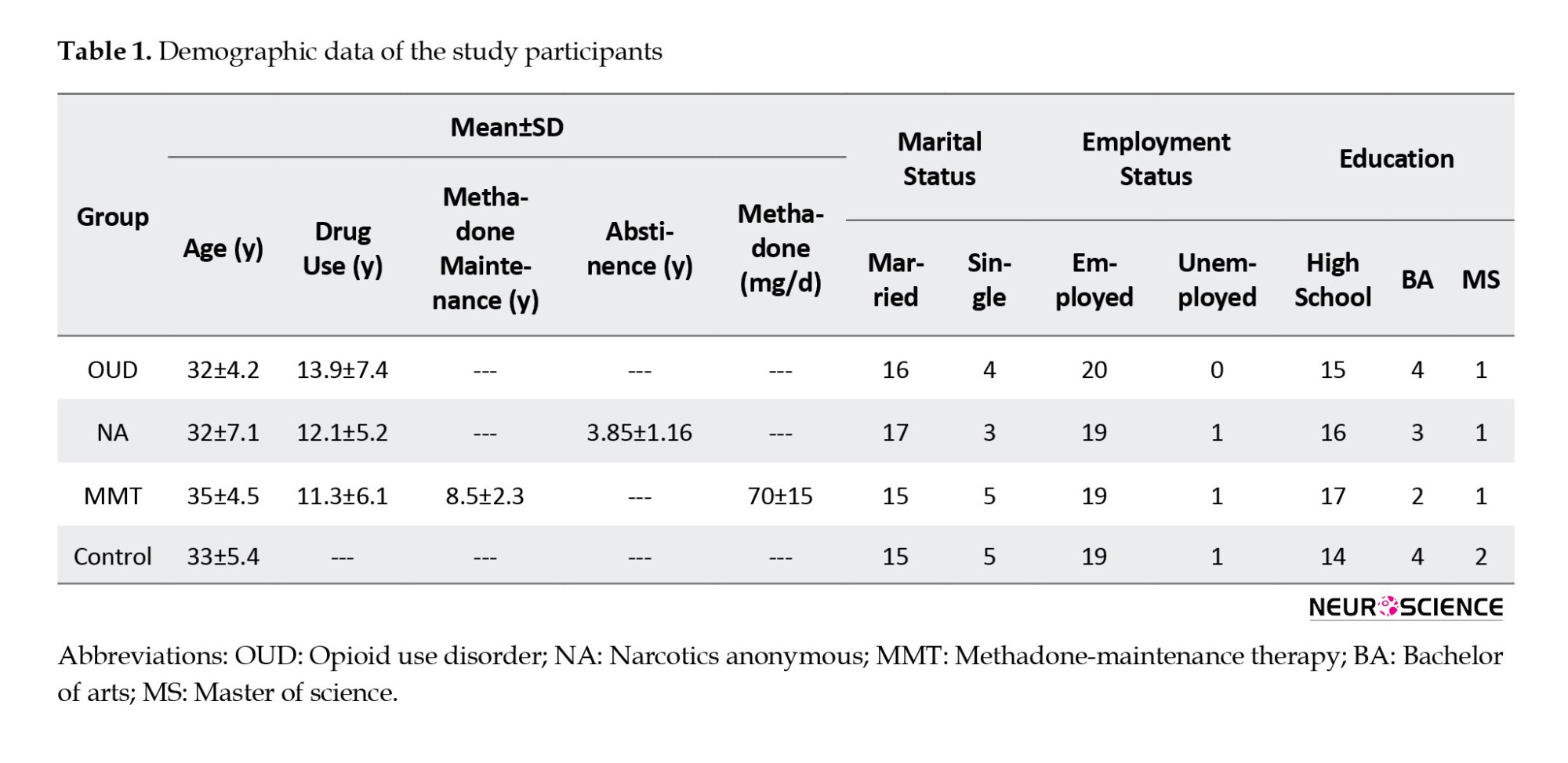

The demographic data of participants is shown in Table 1. We did our best to select subjects so that the characteristics such as age, employment, education, and marital status that could affect the variables assessed in the questionnaires are similar between groups with no significant differences. MANOVA was conducted to determine possible significant differences between the four study groups regarding each variable. Levene’s test results indicated that all study variables’ variances were equal across the four groups (P>0.05).

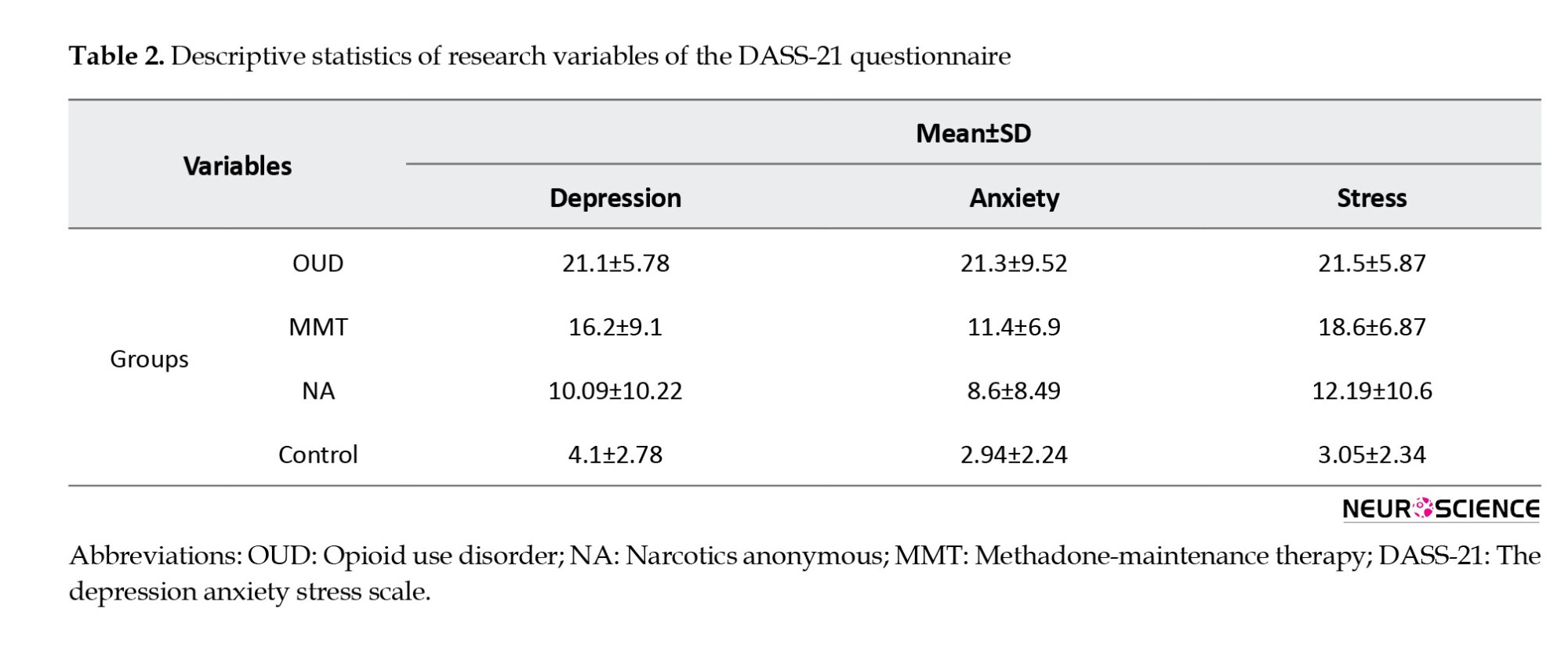

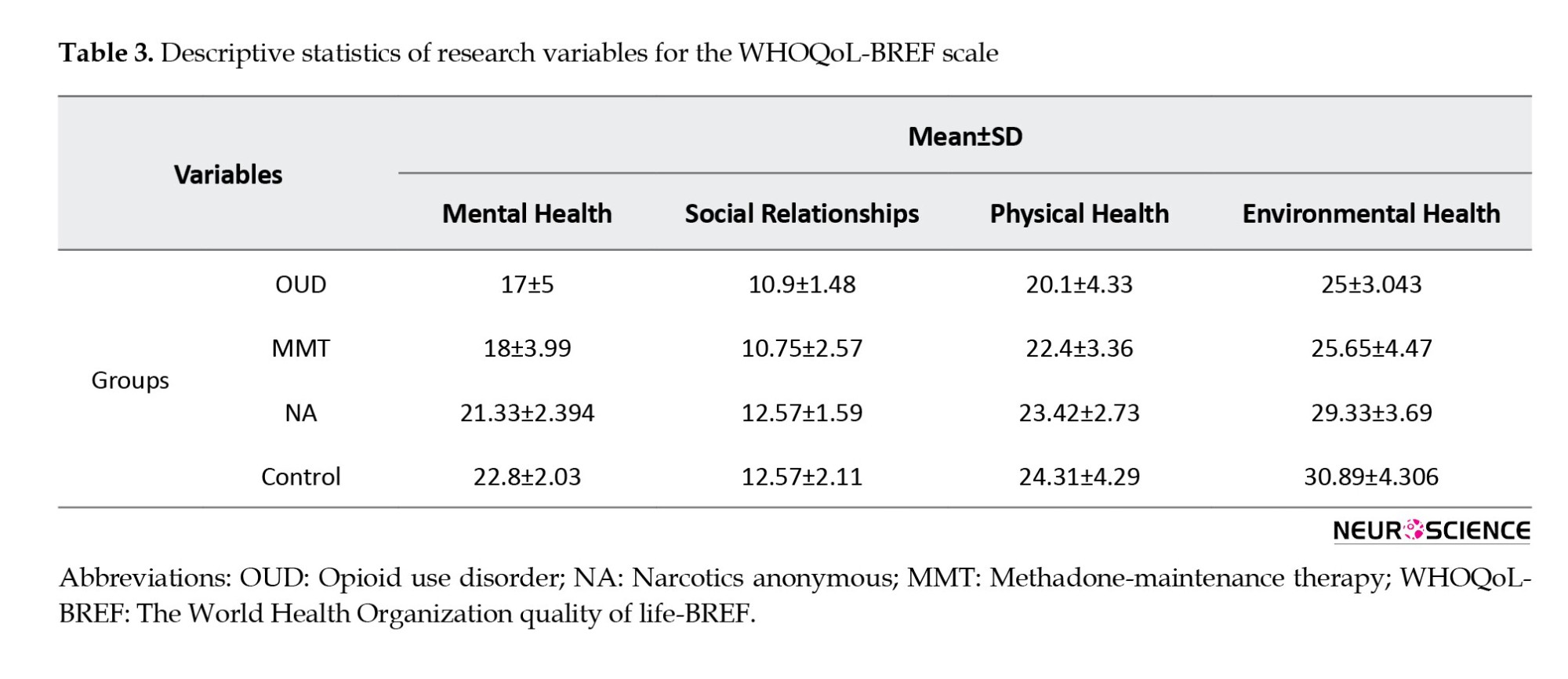

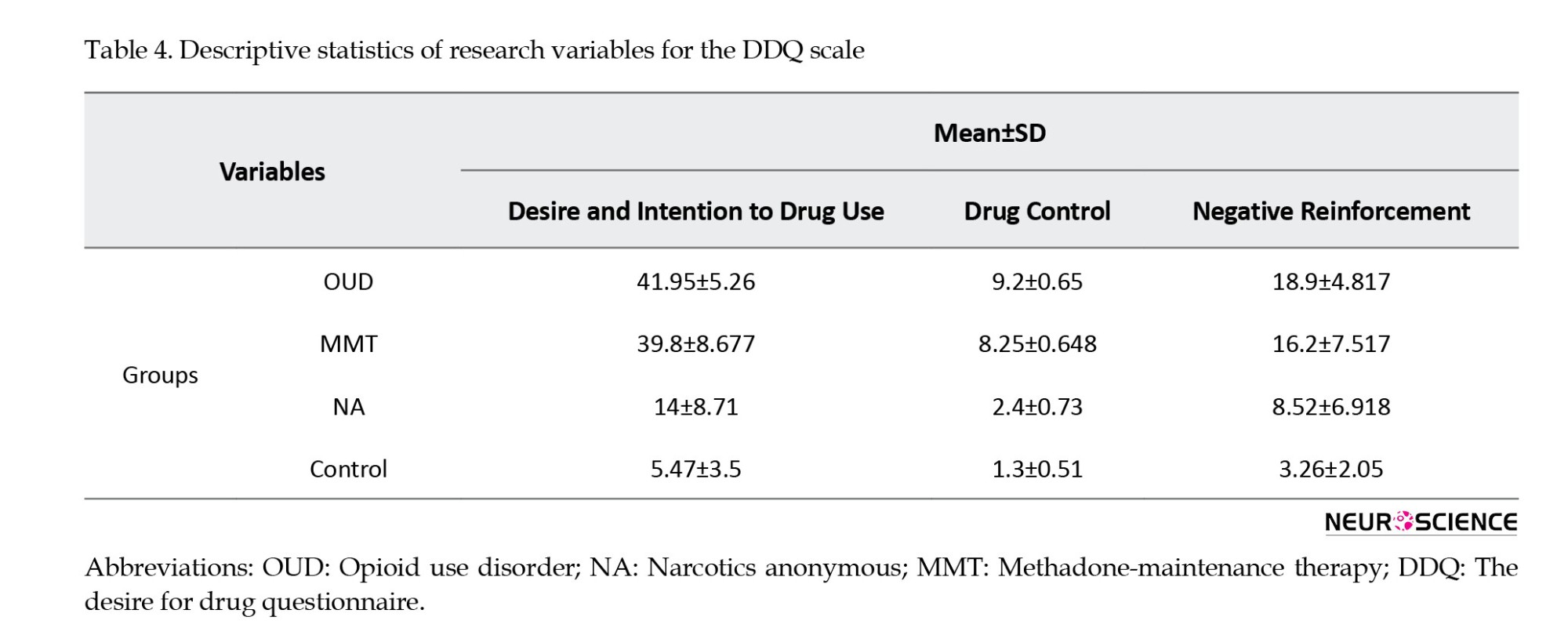

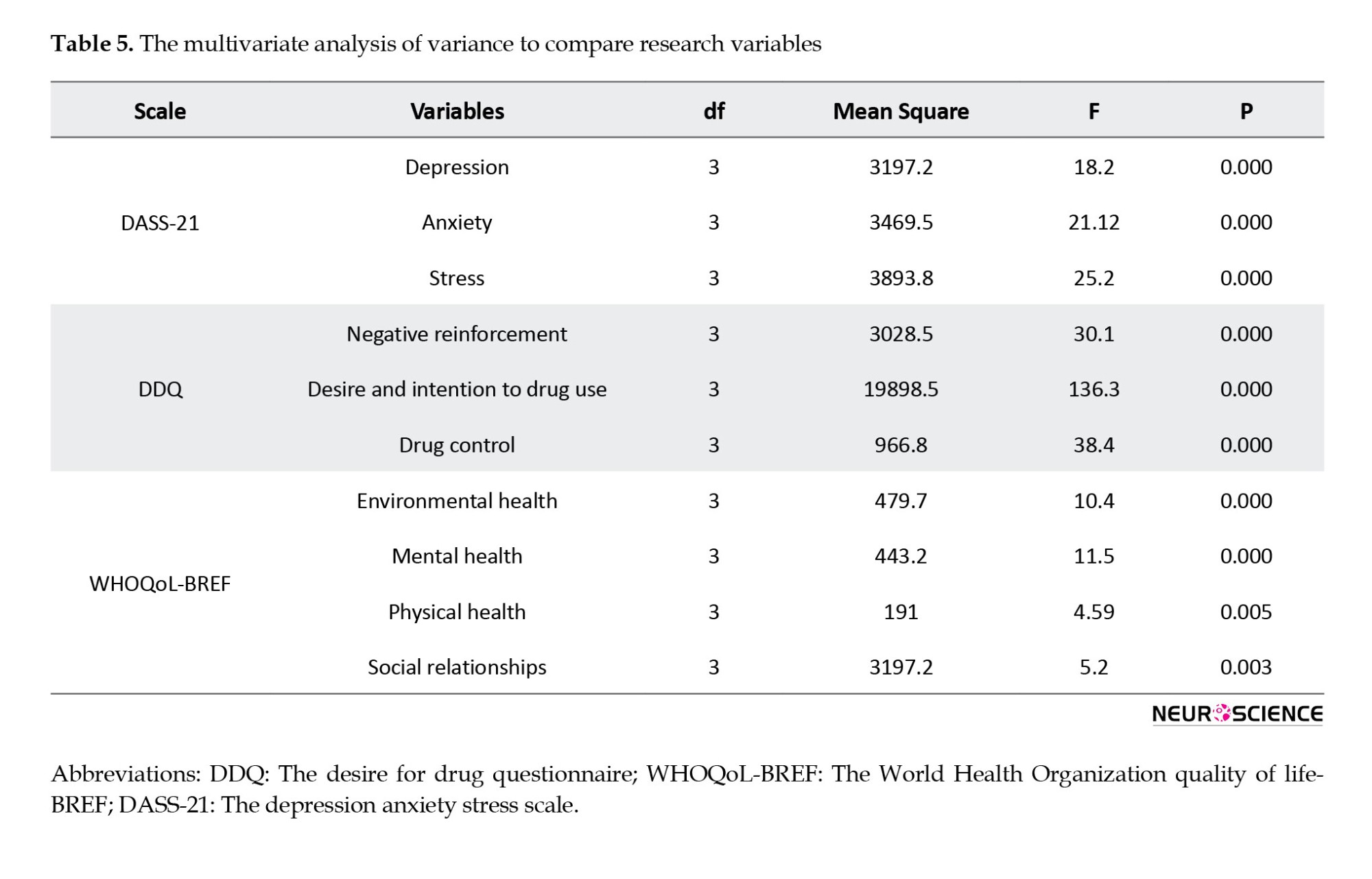

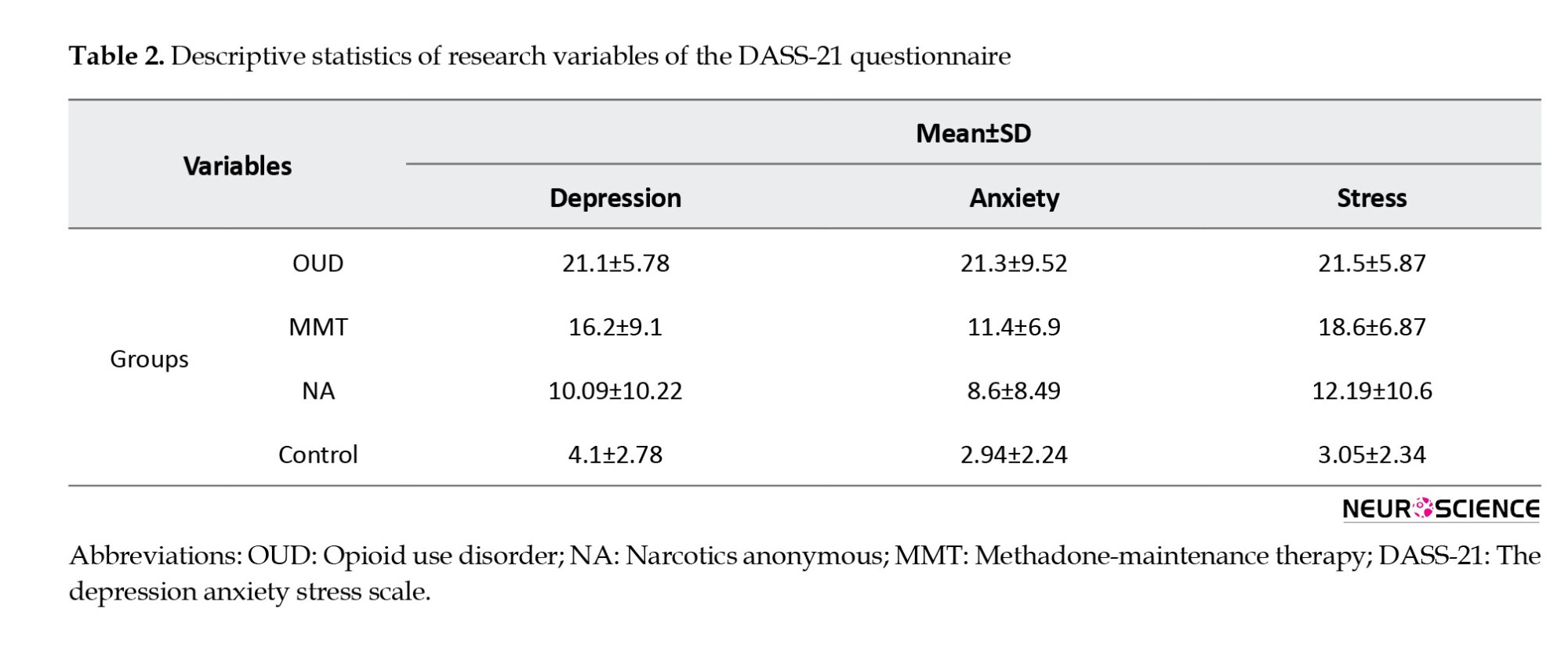

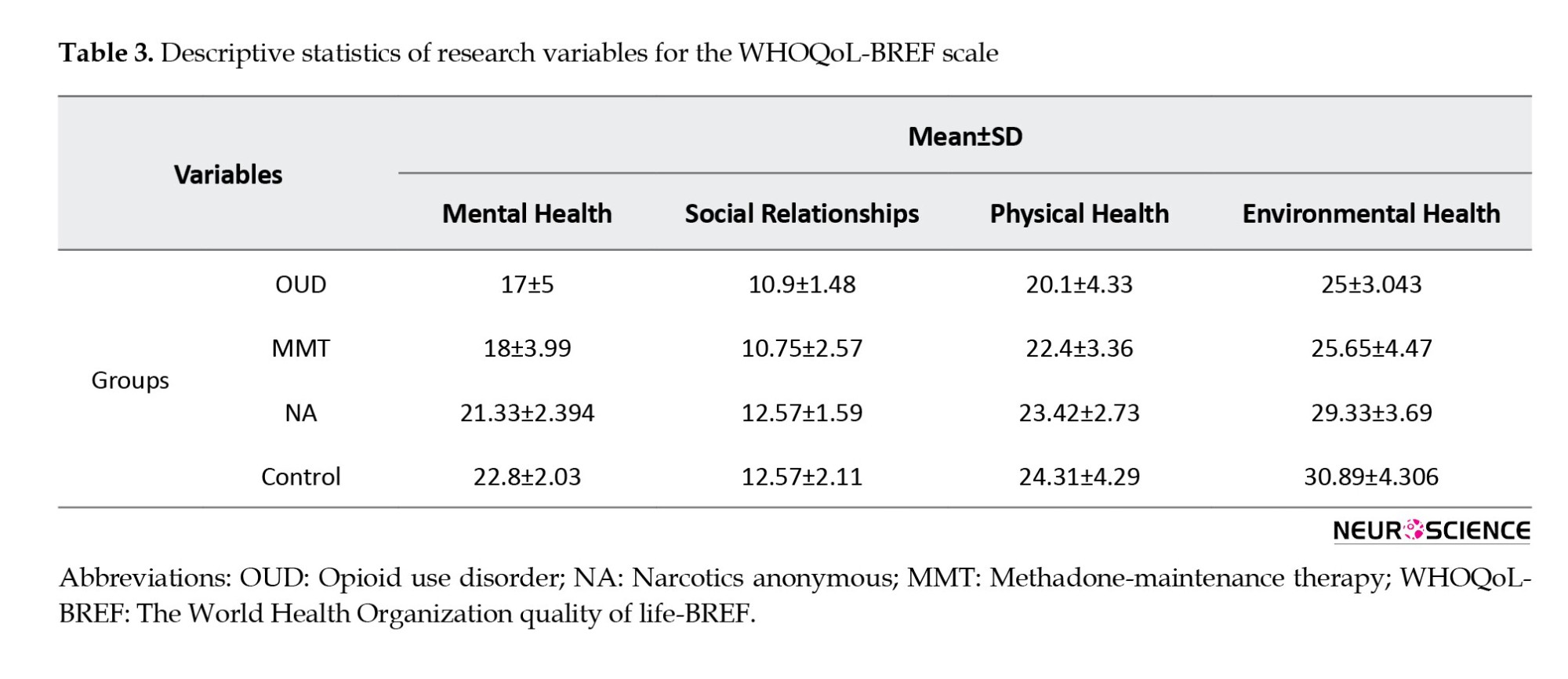

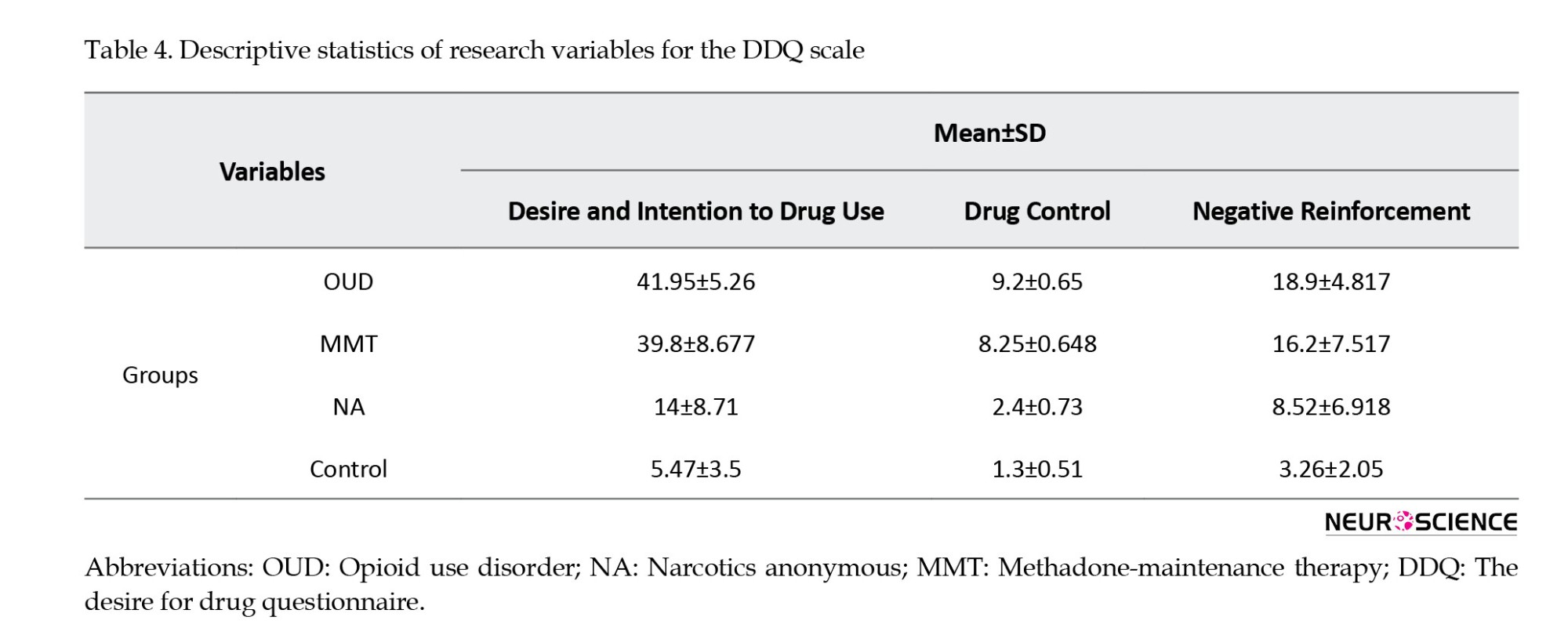

The Wilks’ Lambda test was used to examine the differences between the groups, and the results showed a significant difference between the groups (F=10.39, P<0.001), supporting the overall hypothesis of the study. In other words, the results suggested a significant difference in at least one of the research variables among the four groups. The variable amounts of the DASS-21 questionnaire for all study groups are presented in Table 2. Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate the descriptive statistics of research variables for the WHOQoL-BREF and DDQ scales.

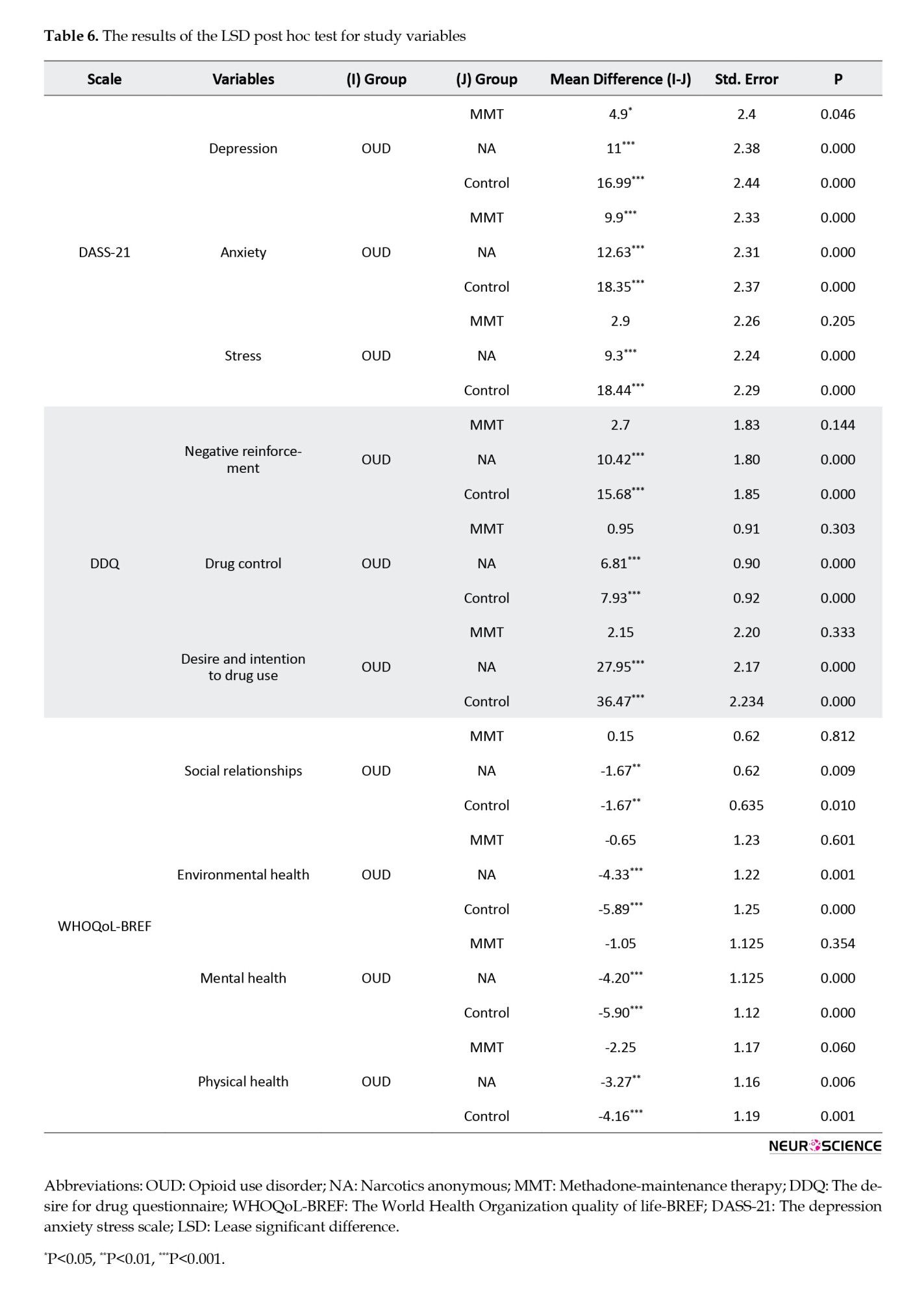

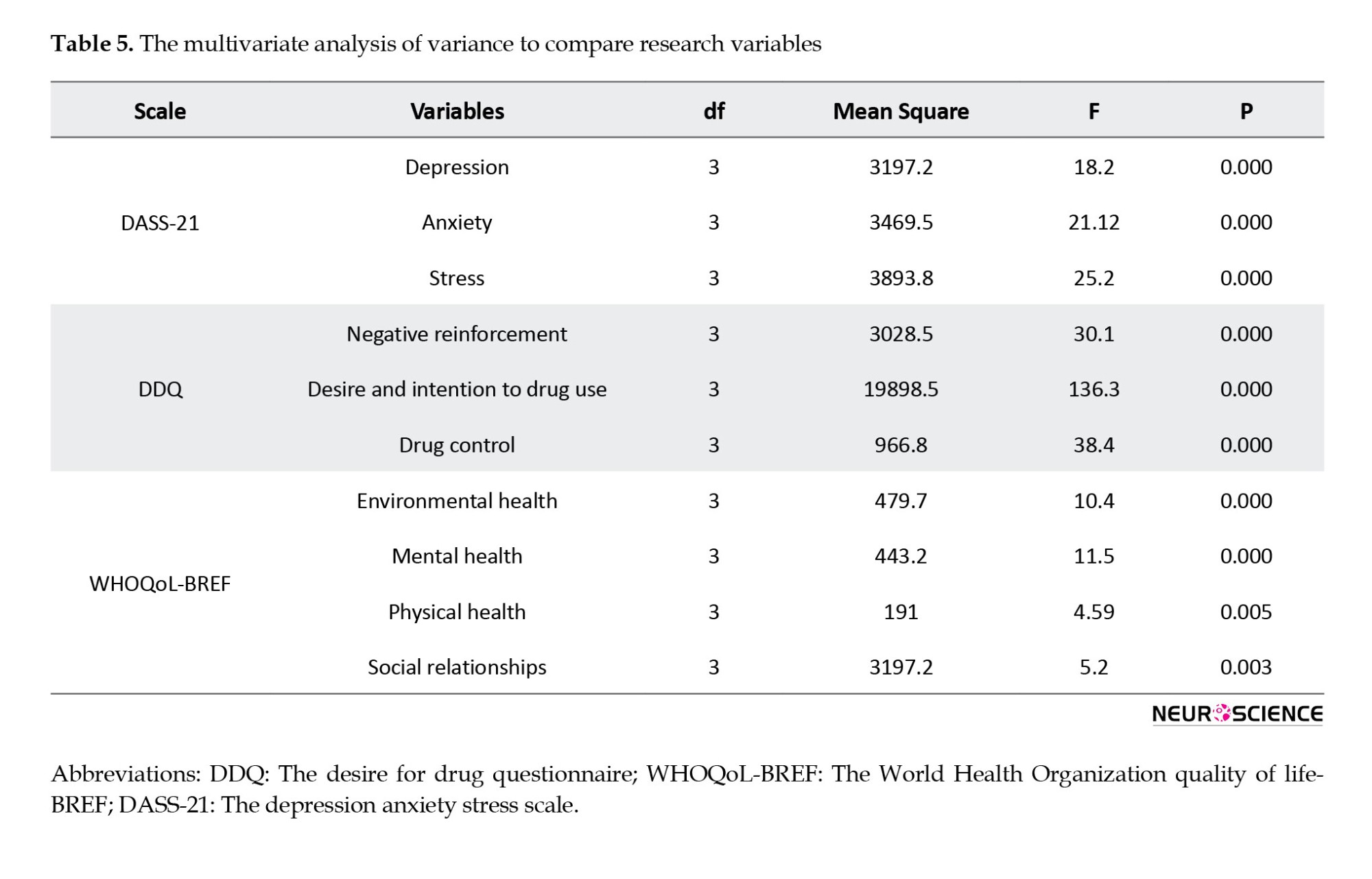

The outcomes of a multivariate analysis of variance with a comparison of study variables are shown in Table 5. The results demonstrated significance in all variables (P<0.05).

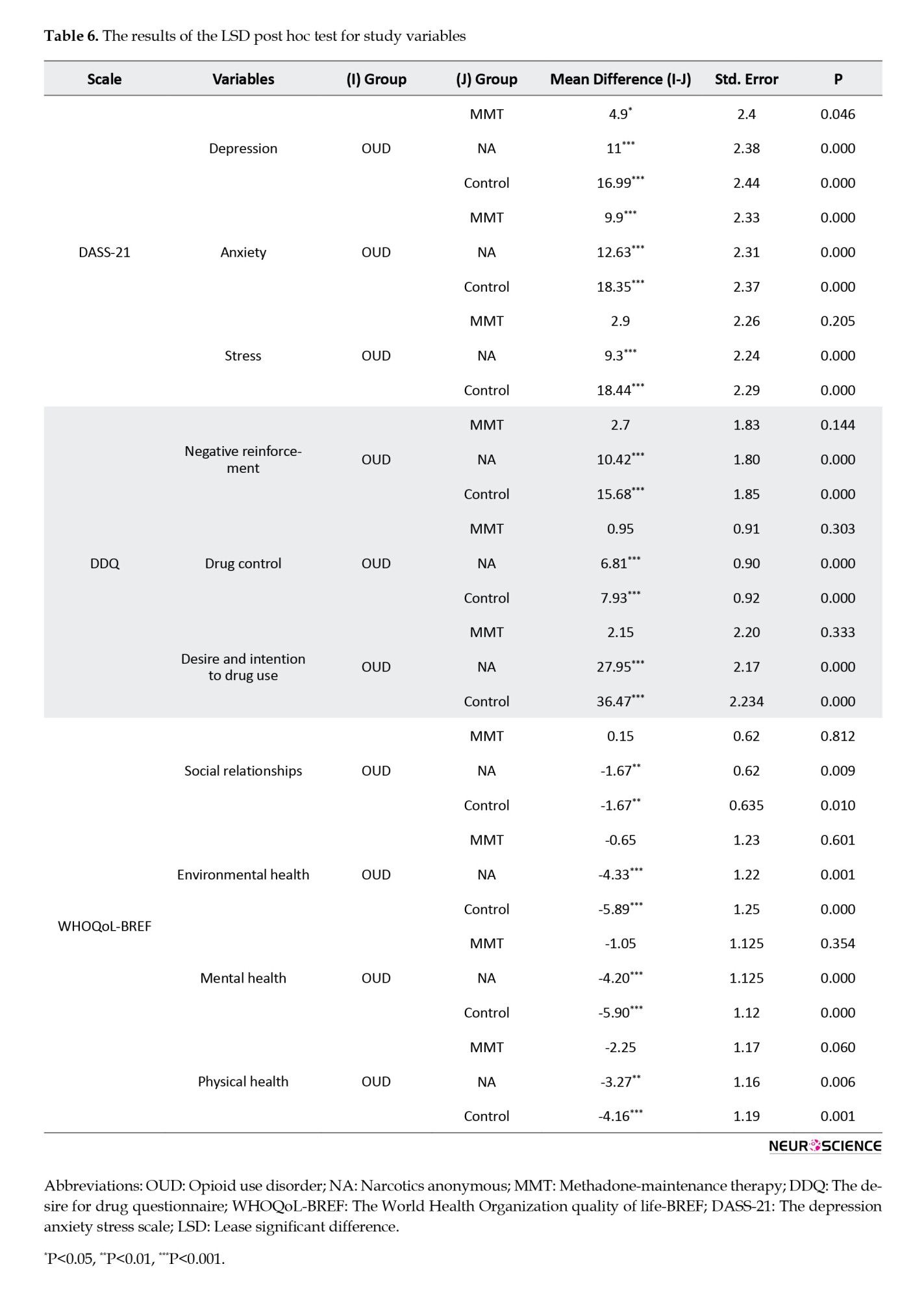

To determine the differences between the four groups in terms of the desired variables, the LSD (least significant difference) post-hoc test was conducted, given the significance of the differences. For the DASS-21 scale, the differences between OUD subjects and each of the other three groups for all variables (depression, anxiety, and stress) were statistically significant except for the difference between OUD and MMT groups for the stress variable that was not significant. For the DDQ scale, the differences between the OUD group and NA or control subjects for all three variables of the scale (Desire and intention to drug use, negative reinforcement, and drug control) were significant. However, these variables were not significantly different between the OUD and MMT groups. The same state was observed for the WHOQoL-BREF scale, the questionnaire variables were statistically different between OUD and NA or control groups. However, the difference between OUD and MMT subjects was not statistically significant. The detailed results are presented in Table 6.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to compare the QoL, the desire for drugs, and the mental health status of individuals with OUD in comparison to MMT, NA, and control subjects to estimate the efficacy of these treatment methods in terms of mental and psychological parameters. A great deal of focus has been placed on the health and QoL of people involved with substance use disorders (Amiri et al., 2010). Several studies have found that these people have a less wealthy QoL than normal individuals (Bizzarri et al., 2005; Schrimshaw & Siegel, 2003; Yen et al., 2011). Some studies have also reported that maintenance treatment with methadone or buprenorphine could improve users’ QoL (Vaarwerk & Gaal, 2001).

The findings of our study showed a significant difference in the level of anxiety and depression between the OUD group and normal individuals, as well as MMT and NA subjects. This finding is consistent with previous research that has shown a high prevalence of anxiety and depression among individuals with OUD (Beaufort et al., 2017; Farnia et al., 2021; Kranzler & Liebowitz, 1988). We also observed that the difference in stress levels between MMT and OUD subjects was not significant. This finding contrasts with some previous studies reporting that maintenance treatment with methadone can reduce stress levels in individuals with OUD (Le et al., 2019; Talebi et al., 2017). This discrepancy may be due to differences in sample size and study design. Nonetheless, our study’s findings regarding the beneficial effects of methadone in reducing anxiety and depression are consistent with previous research (Talebi et al., 2017). An earlier study has also reported that NA groups are more effective than medication-assisted treatment programs in reducing anxiety and depression in individuals with OUD (Haj Hosseini & Hashemi, 2016). According to our findings, the level of depression and anxiety in the NA group was like the control group. Attending NA meetings has been linked to lower levels of anxiety and depression in some studies (Haj Hosseini & Hashemi, 2016). Other studies have found mixed results or no significant differences between NA and other treatments for OUD.

The analysis of the QoL parameters across different groups suggested that having a history of OUD could harm one’s QoL, consistent with previous research (Katibaei, 2010). However, the findings of our study indicated that attending NA meetings can positively affect the QoL, As there was a significant improvement in all aspects of QoL (including physical health and social relationships) for individuals in the NA group. On the other hand, the data indicated no significant improvement in any component of the QoL for the MMT group. Our findings challenge prior studies that have suggested methadone therapy could improve the QoL in areas such as physical health and social functioning (Chou et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2023). The lack of significant improvement in QoL among MMT individuals may be due to various factors, such as the dose and duration of methadone treatment, as well as individual differences in adherence to treatment and engagement in other forms of care. More studies with larger case numbers are needed to be performed in the future to clarify the reasons.

Our data also revealed a significant difference between the OUD group and both the control and NA subjects in the negative reinforcement subscale of the DDQ, suggesting that opioid users may be more likely to use drugs to avoid negative feelings or experiences, such as withdrawal symptoms or anxiety. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that substance use disorder can be driven by negative reinforcement, which is the desire to avoid or alleviate negative feelings or experiences (Tsui et al., 2014; Yen et al., 2016). In a previous study using the DDQ scale to assess individuals with cocaine use disorder, it was found that these people had higher scores on the negative reinforcement subscale of the DDQ compared to non-drug-using controls, suggesting that negative reinforcement plays an essential role in drug use disorders (Yen et al., 2016). Previously, Koob and Le Moal proposed the “dark side” of addiction, which refers to the negative emotional state that can arise during drug withdrawal and contribute to drug-seeking behavior. The authors have hypothesized that the negative reinforcement model of addiction, which emphasizes the role of negative affect in driving drug consumption, may be more accurate than the traditional model of drug use disorder, which focuses on the rewarding properties of drugs (Koob & Le Moal, 2008a; Koob & Le Mal, 2008b). There was no significant difference in the negative reinforcement subscale of the DDQ between the OUD and MMT groups. A possible explanation might be that in this study, the individuals using methadone had a history of long-term use of other drugs. Furthermore, replacement therapy with agonists like methadone, which have a similar underlying mechanism of action (Pathan & Williams, 2012), may not adequately modify the molecular pathways involved in the pathogenesis of OUD. Nevertheless, NA groups may be more effective in the reduction of negative reinforcement, desire to consume, and impulse control of OUD subjects to maintain abstinence and reduce drug use.

5. Conclusion

In summary, the findings of the comparison across the four groups of OUD, MMT, NA, and control demonstrated that supportive NA groups have higher performance and outcome than methadone in terms of QoL and the number of indicators that induce relapse, such as negative reinforcement, the urge to use, and cognitive control. Of course, methadone has been shown to enhance some of these signs; for example, there is a significant decrease in anxiety and depression in the methadone group as compared to the OUD subjects. However, because of the limited sample size of this study, the findings should be considered with caution when generalizing the results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in the study. The Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, approved the protocols and processes for human studies (Code: IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1400.499).

Funding

The research has been conducted with a grant from Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant No.: 1400-1-148-51511).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Nasim Vousooghi; Methodology: Mehdi Tehrani-Doost, and Nasim Vousooghi; Validation: Elahe Motevaseli; Data curation: Parviz Dousti Kataj; Investigation and resources: Narges Dalili; Supervision: Nasim Vousooghi, Mohammad Reza Zarrindast, and Mehdi Tehrani-Doost; Formal analysis: Parviz Dousti Kataj, and Elahe Motevaseli; Project administration and funding acquisition: Nasim Vousooghi; Writing the original draft: Narges Dalili, and Parviz Dousti Kataj; Review & Editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors especially thank their study participants who contributed to this research.

References

Substance use disorder (SUD) is a chronic and recurring condition characterized by obsessive substance seeking and use regardless of the adverse effects (Hser & Anglin, 2011). It is a complicated and difficult problem that impacts individuals, families, and communities worldwide (White & McLellan, 2008). Opioid use disorder (OUD), in particular, has become a major public health concern in recent years, as the rates of abuse and overdose deaths are rising at an alarming figure (Blendon & Benson, 2018). OUD was predicted to affect 26.8 million people worldwide in 2016, and over 100000 people die from opioid overdoses each year, including over 47000 Americans in 2017 (Strang et al., 2020).

OUD is associated with a range of physical health consequences, including respiratory depression, constipation, and an increased risk of infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C (Altice et al., 2010; Dydyk et al., 2022). In addition to the physical health complications, individuals with OUD may encounter various psychological and social challenges that can significantly impact their quality of life (QoL) (Volkow & Blanco, 2021). For example, OUD can result in mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, as well as social isolation, relationship problems, financial difficulties, and legal issues (Colasanti et al., 2011; Emery & Akil, 2020; Nunes et al., 1994; Volkow & Blanco, 2021). QoL is a multidimensional construct encompassing physical, psychological, social, and environmental elements contributing to an individual’s overall well-being (Power et al., 1999). In the context of OUD, QoL may be adversely impacted by a range of factors, including chronic pain, impaired functioning, financial difficulties, and social stigma (Hagemeier, 2018). Besides, a person’s QoL can be greatly impacted by typical mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and stress, which are also experienced often by people involved with OUD.

Opioid craving is a fundamental feature of OUD and is defined as an intense urge or desire to use drugs (Sayette, 2016). The desire can be so strong that it can overcome a person’s willingness to regulate his/her drug use, ultimately resulting in a relapse (Witkiewitz & Bowen, 2010). Craving is considered one of the major barriers to long-term recovery from OUD (Sayette, 2016) and can be caused by both physiological and psychological factors. Physiologically, it is related to changes in brain function and the release of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, which are associated with reward and pleasure (Wise & Robble, 2020). Psychologically, it can be triggered by a range of external and internal cues, such as stress, negative emotions, physical withdrawal symptoms, and drug-related environments or stimuli (Suzuki et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Understanding the factors that contribute to substance craving can help individuals and healthcare providers develop effective treatment plans to overcome SUD. The psychological component of craving can be related to the individual’s thoughts, emotions, and memories related to drug use (Brewer et al., 2013). Therefore, effective addiction treatment should address both the physiological and psychological aspects of substance craving to help people manage their urges and achieve and maintain recovery.

Several treatment approaches, such as medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and support groups like narcotics anonymous (NA), are available for patients involved with OUD (Carroll & Onken, 2005; Davis et al., 2005). In MAT, medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone are used to manage withdrawal symptoms and diminish craving (Alderks, 2017). Supportive groups such as NA provide a beneficial community for individuals in recovery and can help to reduce social isolation and stigma of OUD and improve the patient’s QoL without using replacement medications (Anderson & Ripullo, 1996).

Much research has been conducted to find out which treatment of OUD could better overcome mental health issues like depression, anxiety, and stress in patients. In addition, the superiority of different treatment methods regarding the dimensions of QoL and substance craving is an important question raised by healthcare providers. The current study was designed to investigate such questions by comparing OUD, methadone-maintenance therapy (MMT), and NA groups with control subjects regarding the scales of mental health issues, QoL, and substance craving.

2. Materials and Methods

Study participants

This cross-sectional study was performed in 2020 and included 80 male participants between the ages of 20 and 45, with 20 participants in each of the following four groups: 1) Subjects with OUD, 2) NA members previously involved with OUD who were drug-free for at least one year at the time of enrollment in the study, 3) Individuals receiving methadone maintenance treatment previously suffering from OUD who were consuming methadone for at least six months, and 4) Control people without a history of OUD. MMT clinics and NA communities in Tehran City were used to recruit participants for the first three groups. Control subjects were selected from students and staff of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The sample size was determined using power analysis, which was based on the effect size of previous studies that examined the same or similar variables, with a power of 0.80 and an alpha level of 0.05. The inclusion criteria of the study were male individuals aged 20 to 45 years, opioid addiction or NA membership or methadone use (for the corresponding groups), and no history of substance use disorder (for the control group). The exclusion criteria were having a history of psychotic disorder or severe mental illness and being currently in an acute phase of withdrawal.

All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in the study. The Ethics Committee approved the protocols and processes for human studies at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Study measures

QoL

QoL was measured using the World Health Organization (WHO) QoL-BREF (WHOQoL-BREF) scale, which was also validated in Irani-an subjects (Usefy et al., 2010).

The WHO defines QoL as a person’s perception of their place in life concerning their goals, aspirations, standards, and concerns in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live (Dimitrova, 2005). These qualities are classified into physical health, mental health, social relationships, and environmental health. The questions are ranked on a Likert scale, with items scoring between 1 and 5. The WHOQoL-BREF has been found to have good internal consistency, with Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.66 to 0.82 across different domains and cultures. The test re-test reliability of the tool is high, with intra-class correla-tion coefficients ranging from 0.70 to 0.90 (Skevington et al., 2004). A study to examine the Persian version of the questionnaire in Iran found that the WHOQoL-BREF scale had good reliability, with Cronbach α values ranging from 0.76 to 0.82 for the domains measured. In addi-tion, the intra-class correlation exceeded 0.7 for all domains (Usefy et al., 2010).

Depression, anxiety, and stress

Depression, anxiety, and stress were measured using the depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21) (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), which is a widely used tool for measuring symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. It consists of 21 items, 7 for each domain (Oei et al., 2013). The DASS-21 has shown good reliability and validity in numerous studies. Internal consistency is high for all three domains, with Cronbach α coefficients ranging from 0.78 to 0.97 (Henry & Crawford, 2005). Also, in the Persian version, the DASS-21 was found to have good reliability and validity. Internal consistency for all three domains is high, and Cronbach's α coefficients range from 0.82 to 0.95 (Asghari et al., 2008; Kakemam et al., 2022).

The desire for drug

The desire for drug questionnaire (DDQ) (Persian version) includes 13 questions that measure three main components of drug craving, desire and intention to use (7 questions), negative reinforcement (4 questions), and control (2 questions). One question was added to enhance the internal consistency of the harmful reinforcement component. The questionnaire uses a seven-point Likert scale to rate the intensity of feelings or thoughts related to drug use, ranging from “not at all” to “approximately complete.”

The internal consistency of the measured variables was high for the first two factors, with coefficients of 0.89 and 0.79. However, the third factor had a low internal consistency with a coefficient of 0.4. in the Persian version (Hassani-Abharian et al., 2016).

Study procedure

WHOQoL-BREF, DASS, and DDQ scales were completed face-to-face at a clinic. The questionnaires were filled in by a trained research assistant who was available to answer any query raised by the participants. The completion of the scales took approximately 30-45 min. Ethical considerations were taken into account in this study, including protecting participants’ privacy and confidentiality and minimizing potential inconveniences for participants.

Data analysis

The data obtained from the scales were analyzed using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to examine differences between the four groups on the dependent variables. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 21, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

The demographic data of participants is shown in Table 1. We did our best to select subjects so that the characteristics such as age, employment, education, and marital status that could affect the variables assessed in the questionnaires are similar between groups with no significant differences. MANOVA was conducted to determine possible significant differences between the four study groups regarding each variable. Levene’s test results indicated that all study variables’ variances were equal across the four groups (P>0.05).

The Wilks’ Lambda test was used to examine the differences between the groups, and the results showed a significant difference between the groups (F=10.39, P<0.001), supporting the overall hypothesis of the study. In other words, the results suggested a significant difference in at least one of the research variables among the four groups. The variable amounts of the DASS-21 questionnaire for all study groups are presented in Table 2. Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate the descriptive statistics of research variables for the WHOQoL-BREF and DDQ scales.

The outcomes of a multivariate analysis of variance with a comparison of study variables are shown in Table 5. The results demonstrated significance in all variables (P<0.05).

To determine the differences between the four groups in terms of the desired variables, the LSD (least significant difference) post-hoc test was conducted, given the significance of the differences. For the DASS-21 scale, the differences between OUD subjects and each of the other three groups for all variables (depression, anxiety, and stress) were statistically significant except for the difference between OUD and MMT groups for the stress variable that was not significant. For the DDQ scale, the differences between the OUD group and NA or control subjects for all three variables of the scale (Desire and intention to drug use, negative reinforcement, and drug control) were significant. However, these variables were not significantly different between the OUD and MMT groups. The same state was observed for the WHOQoL-BREF scale, the questionnaire variables were statistically different between OUD and NA or control groups. However, the difference between OUD and MMT subjects was not statistically significant. The detailed results are presented in Table 6.

4. Discussion

The current study aimed to compare the QoL, the desire for drugs, and the mental health status of individuals with OUD in comparison to MMT, NA, and control subjects to estimate the efficacy of these treatment methods in terms of mental and psychological parameters. A great deal of focus has been placed on the health and QoL of people involved with substance use disorders (Amiri et al., 2010). Several studies have found that these people have a less wealthy QoL than normal individuals (Bizzarri et al., 2005; Schrimshaw & Siegel, 2003; Yen et al., 2011). Some studies have also reported that maintenance treatment with methadone or buprenorphine could improve users’ QoL (Vaarwerk & Gaal, 2001).

The findings of our study showed a significant difference in the level of anxiety and depression between the OUD group and normal individuals, as well as MMT and NA subjects. This finding is consistent with previous research that has shown a high prevalence of anxiety and depression among individuals with OUD (Beaufort et al., 2017; Farnia et al., 2021; Kranzler & Liebowitz, 1988). We also observed that the difference in stress levels between MMT and OUD subjects was not significant. This finding contrasts with some previous studies reporting that maintenance treatment with methadone can reduce stress levels in individuals with OUD (Le et al., 2019; Talebi et al., 2017). This discrepancy may be due to differences in sample size and study design. Nonetheless, our study’s findings regarding the beneficial effects of methadone in reducing anxiety and depression are consistent with previous research (Talebi et al., 2017). An earlier study has also reported that NA groups are more effective than medication-assisted treatment programs in reducing anxiety and depression in individuals with OUD (Haj Hosseini & Hashemi, 2016). According to our findings, the level of depression and anxiety in the NA group was like the control group. Attending NA meetings has been linked to lower levels of anxiety and depression in some studies (Haj Hosseini & Hashemi, 2016). Other studies have found mixed results or no significant differences between NA and other treatments for OUD.

The analysis of the QoL parameters across different groups suggested that having a history of OUD could harm one’s QoL, consistent with previous research (Katibaei, 2010). However, the findings of our study indicated that attending NA meetings can positively affect the QoL, As there was a significant improvement in all aspects of QoL (including physical health and social relationships) for individuals in the NA group. On the other hand, the data indicated no significant improvement in any component of the QoL for the MMT group. Our findings challenge prior studies that have suggested methadone therapy could improve the QoL in areas such as physical health and social functioning (Chou et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2023). The lack of significant improvement in QoL among MMT individuals may be due to various factors, such as the dose and duration of methadone treatment, as well as individual differences in adherence to treatment and engagement in other forms of care. More studies with larger case numbers are needed to be performed in the future to clarify the reasons.

Our data also revealed a significant difference between the OUD group and both the control and NA subjects in the negative reinforcement subscale of the DDQ, suggesting that opioid users may be more likely to use drugs to avoid negative feelings or experiences, such as withdrawal symptoms or anxiety. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that substance use disorder can be driven by negative reinforcement, which is the desire to avoid or alleviate negative feelings or experiences (Tsui et al., 2014; Yen et al., 2016). In a previous study using the DDQ scale to assess individuals with cocaine use disorder, it was found that these people had higher scores on the negative reinforcement subscale of the DDQ compared to non-drug-using controls, suggesting that negative reinforcement plays an essential role in drug use disorders (Yen et al., 2016). Previously, Koob and Le Moal proposed the “dark side” of addiction, which refers to the negative emotional state that can arise during drug withdrawal and contribute to drug-seeking behavior. The authors have hypothesized that the negative reinforcement model of addiction, which emphasizes the role of negative affect in driving drug consumption, may be more accurate than the traditional model of drug use disorder, which focuses on the rewarding properties of drugs (Koob & Le Moal, 2008a; Koob & Le Mal, 2008b). There was no significant difference in the negative reinforcement subscale of the DDQ between the OUD and MMT groups. A possible explanation might be that in this study, the individuals using methadone had a history of long-term use of other drugs. Furthermore, replacement therapy with agonists like methadone, which have a similar underlying mechanism of action (Pathan & Williams, 2012), may not adequately modify the molecular pathways involved in the pathogenesis of OUD. Nevertheless, NA groups may be more effective in the reduction of negative reinforcement, desire to consume, and impulse control of OUD subjects to maintain abstinence and reduce drug use.

5. Conclusion

In summary, the findings of the comparison across the four groups of OUD, MMT, NA, and control demonstrated that supportive NA groups have higher performance and outcome than methadone in terms of QoL and the number of indicators that induce relapse, such as negative reinforcement, the urge to use, and cognitive control. Of course, methadone has been shown to enhance some of these signs; for example, there is a significant decrease in anxiety and depression in the methadone group as compared to the OUD subjects. However, because of the limited sample size of this study, the findings should be considered with caution when generalizing the results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in the study. The Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, approved the protocols and processes for human studies (Code: IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1400.499).

Funding

The research has been conducted with a grant from Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant No.: 1400-1-148-51511).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Nasim Vousooghi; Methodology: Mehdi Tehrani-Doost, and Nasim Vousooghi; Validation: Elahe Motevaseli; Data curation: Parviz Dousti Kataj; Investigation and resources: Narges Dalili; Supervision: Nasim Vousooghi, Mohammad Reza Zarrindast, and Mehdi Tehrani-Doost; Formal analysis: Parviz Dousti Kataj, and Elahe Motevaseli; Project administration and funding acquisition: Nasim Vousooghi; Writing the original draft: Narges Dalili, and Parviz Dousti Kataj; Review & Editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors especially thank their study participants who contributed to this research.

References

Alderks: C. E. (2017). Trends in the use of methadone: buprenorphine: and extended-release naltrexone at substance abuse treatment facilities: 2003-2015 (update). In The CBHSQ Report (pp. 1–8). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). [PMID]

Altice, F. L., Kamarulzaman, A., Soriano, V. V., Schechter, M., & Friedland, G. H. (2010). Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet (London, England), 376(9738), 367–387. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X] [PMID]

Amiri, M., Khosravi, A., & Chaman, R. (2010). Drug abuse pattern and high risk behaviors among addicts in Shahroud County of Semnan Province, Northeast Iran in 2009. Journal of Research in Health Sciences, 10(2), 104–109. [PMID]

Anderson, T. L., & Ripullo, F. (1996). Social setting: Stigma management: and recovering drug addicts. Humanity & Society: 20(3), 25-43. [DOI:10.1177/016059769602000304]

Asghari, A., Saed, F., & Dibajnia, P. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) in a non-clinical Iranian sample. IPA International Journal of Psychology, 2(2), 82-102. [Link]

Beaufort, I. N., De Weert-Van Oene, G. H., Buwalda, V. A. J., de Leeuw, J. R. J., & Goudriaan, A. E. (2017). The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) as a Screener for Depression in Substance Use Disorder Inpatients: A Pilot Study. European Addiction Research, 23(5), 260–268. [DOI:10.1159/000485182] [PMID]

Bizzarri, J., Rucci, P., Vallotta, A., Girelli, M., Scandolari, A., & Zerbetto, E., et al. (2005). Dual diagnosis and quality of life in patients in treatment for opioid dependence. Substance Use & Misuse, 40(12), 1765–1776. [DOI:10.1080/10826080500260800] [PMID]

Blendon, R. J., & Benson, J. M. (2018). The public and the opioid-abuse epidemic. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(5), 407–411. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMp1714529] [PMID]

Brewer, J. A., Elwafi, H. M., & Davis, J. H. (2013). Craving to quit: Psychological models and neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness training as treatment for addictions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(2), 366–379. [DOI:10.1037/a0028490] [PMID]

Carroll, K. M., & Onken, L. S. (2005). Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(8), 1452–1460. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1452] [PMID]

Chou, Y. C., Shih, S. F., Tsai, W. D., Li, C. S., Xu, K., & Lee, T. S. (2013). Improvement of quality of life in methadone treatment patients in northern Taiwan: A follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 190. [DOI:10.1186/1471-244X-13-190] [PMID]

Colasanti, A., Rabiner, E. A., Lingford-Hughes, A., & Nutt, D. J. (2011). Opioids and anxiety. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 25(11), 1415–1433. [DOI:10.1177/0269881110367726] [PMID]

Davis, L. L., Rush, J. A., Wisniewski, S. R., Rice, K., Cassano, P., & Jewell, M. E., et al. (2005). Substance use disorder comorbidity in major depressive disorder: An exploratory analysis of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression cohort. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 46(2), 81-89. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.07.025] [PMID]

Dimitrova, B. (2005). Carr A J, Higginson I J, Robinson P G, (editors). Quality of life. London: BMJ Books, 2003. 133 pp. ISBN 0-7279-1544-4. European Journal of Public Health, 15(6), 668. [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/cki178]

Dydyk, A. M., Jain, N. K., & Gupta, M. (2024). Opioid use disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. [PMID]

Emery, M. A., & Akil, H. (2020). Endogenous opioids at the intersection of opioid addiction, pain, and depression: The search for a precision medicine approach. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 43, 355–374. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-neuro-110719-095912] [PMID]

Farnia, V., Afshari, D., Abdoli, N., Radmehr, F., Moradinazar, M., & Alikhani, M., et al. (2021). The effect of substance abuse on depression, anxiety, and stress (DASS-21) in epileptic patients. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 9, 128-131. [DOI:10.1016/j.cegh.2020.08.001]

Hagemeier, N. E. (2018). Introduction to the opioid epidemic: The economic burden on the healthcare system and impact on quality of life. The American Journal of Managed Care, 24(10 Suppl), S200-S206. [Link]

Haj Hosseini, M., & Hashemi, R. (2016). Addicts’ quality of life and psychological disorders (depression, anxiety, and stress) in two treatment methods: Narcotics anonymous vs. methadone maintenance treatment. Scientific Quarterly Research on Addiction, 9(35), 119-136. [Link]

Hassani-Abharian, P., Mokri, A., Ganjgahi, H., Oghabian, M. A., & Ekhtiari, H. (2016). Validation for Persian versions of “desire for drug questionnaire” and “obsessive compulsive drug use scale” in heroin dependents. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 19(9), 659-665. [Link]

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short‐form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS‐21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non‐clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(Pt 2), 227–239.[DOI:10.1348/014466505X29657] [PMID]

Hser, Y. I., & Anglin, M. D. (2011). Addiction treatment and recovery careers. Addiction recovery management: Theory: research and practice: In: Kelly, J. F., & White, W. L (Ed.) Addiction Recovery Management Theory, Research and Practice. pp. 9-29. New Jersey: Humana Press [DOI: 10.1007/978-1-60327-960-4_2]

Kakemam, E., Navvabi, E., Albelbeisi, A. H., Saeedikia, F., Rouhi, A., & Majidi, S. (2022). Psychometric properties of the Persian version of Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 Items (DASS-21) in a sample of health professionals: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 111.[DOI:10.1186/s12913-022-07514-4] [PMID]

Katibaei, J. (2010). [Comparison of quality of life, stress and mental health of addicts and non-addicts affected by HIV and healthy individuals (Persian)]. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 4(2), 135-139. [Link]

Kim, J. J., Nikoo, M., Nikoo, N., Javidanbardan, S., Kazemi, A., & Choi, F., et al. (2023). Quality of life of patients treated with opium tincture or methadone: A randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 249, 110874. [DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.110874] [PMID]

Koob, G. F., & Le Moal, M. (2008). Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 29–53. [DOI:10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548] [PMID]

Koob, G. F., & Le Moal, M. (2008). Review. Neurobiological mechanisms for opponent motivational processes in addiction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 363(1507), 3113–3123.[DOI:10.1098/rstb.2008.0094] [PMID]

Kranzler, H. R., & Liebowitz, N. R. (1988). Anxiety and depression in substance abuse: Clinical implications. The Medical Clinics of North America, 72(4), 867–885. [DOI:10.1016/S0025-7125(16)30749-0] [PMID]

Le, T. A., Le, M. Q. T., Dang, A. D., Dang, A. K., Nguyen, C. T., & Pham, H. Q., et al. (2019). Multi-level predictors of psychological problems among methadone maintenance treatment patients in difference types of settings in Vietnam. Substance Abuse Treatment: Prevention: and Policy, 14(1), 39. [DOI:10.1186/s13011-019-0223-4] [PMID]

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343.[DOI:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u] [PMID]

Nunes, E. V., Donovan, S. J., Brady, R., & Quitkin, F. M. (1994). Evaluation and treatment of mood and anxiety disorders in opioid-dependent patients. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 26(2), 147–153. [DOI:10.1080/02791072.1994.10472262] [PMID]

Oei, T. P., Sawang, S., Goh, Y. W., & Mukhtar, F. (2013). Using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) across cultures. International Journal of Psychology: Journal International de Psychologie, 48(6), 1018–1029. [DOI:10.1080/00207594.2012.755535] [PMID]

Pathan, H., & Williams, J. (2012). Basic opioid pharmacology: An update. British Journal of Pain, 6(1), 11-16. [DOI:10.1177/2049463712438493] [PMID]

Power, M., Harper, A., & Bullinger, M. (1999). The World Health Organization WHOQoL-100: Tests of the universality of Quality of Life in 15 different cultural groups worldwide. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 18(5), 495–505. [DOI:10.1037/0278-6133.18.5.495] [PMID]

Sayette, M. A. (2016). The role of craving in substance use disorders: Theoretical and methodological issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 407-433. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093351] [PMID]

Schrimshaw, E. W., & Siegel, K. (2003). Perceived barriers to social support from family and friends among older adults with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Health Psychology, 8(6), 738-752. [DOI:10.1177/13591053030086007] [PMID]

Skevington, S. M., Lotfy, M., O'Connell, K. A., & WHOQoL Group (2004). The World Health Organization's WHOQoL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQoL group. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 13(2), 299–310. [DOI:10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00] [PMID]

Strang, J., Volkow, N. D., Degenhardt, L., Hickman, M., Johnson, K., & Koob, G. F., et al. (2020). Opioid use disorder. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 6(1), 3. [DOI:10.1038/s41572-019-0137-5] [PMID]

Suzuki, S., Mell, M. M., O'Malley, S. S., Krystal, J. H., Anticevic, A., & Kober, H. (2020). Regulation of craving and negative emotion in alcohol use disorder. Biological Psychiatry. Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 5(2), 239–250. [DOI:10.1016/j.bpsc.2019.10.005] [PMID]

Talebi, M., Zavar, A., Ghafari, M., & Poorandy, R. (2017). Improvement of quality of life and mental health in methadone maintenance therapy. MOJ Addiction Medicine & Therapy, 3(3), 82-89. [DOI:10.15406/mojamt.2017.03.00039]

Tsui, J. I., Anderson, B. J., Strong, D. R., & Stein, M. D. (2014). Craving predicts opioid use in opioid-dependent patients initiating buprenorphine treatment: A longitudinal study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(2), 163-169. [DOI:10.3109/00952990.2013.848875] [PMID]

Yousefy, A. R., Ghassemi, G. R., Sarrafzadegan, N., Mallik, S., Baghaei, A. M., & Rabiei, K. (2010). Psychometric properties of the WHOQoL-BREF in an Iranian adult sample. Community Mental Health Journal, 46(2), 139–147. [DOI:10.1007/s10597-009-9282-8] [PMID]

te Vaarwerk, M. J., & Gaal, E. A. (2001). Psychological distress and quality of life in drug-using and non-drug-using HIV-infected women. European Journal of Public Health, 11(1), 109–115. [DOI:10.1093/eurpub/11.1.109] [PMID]

Volkow, N. D., & Blanco, C. (2021). The changing opioid crisis: Development, challenges and opportunities. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(1), 218–233. [DOI:10.1038/s41380-020-0661-4] [PMID]

White, W., & McLellan, A. (2008). Addiction as a chronic disease: Key messages for clients: Families and referral sources. Retrieved from: [Link]

Wise, R. A., & Robble, M. A. (2020). Dopamine and Addiction. Annual Review of Psychology, 71, 79–106. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103337] [PMID]

Witkiewitz, K., & Bowen, S. (2010). Depression, craving, and substance use following a randomized trial of mindfulness-based relapse prevention. Journal of Consulting and clinical Psychology, 78(3), 362–374. [DOI:10.1037/a0019172] [PMID]

Wu, L. L., Potenza, M. N., Zhou, N., Kober, H., Shi, X. H., & Yip, S. W., et al. (2020). A role for the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in enhancing regulation of both craving and negative emotions in internet gaming disorder: A randomized trial. European Neuropsychopharmacology: The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 36, 29–37. [DOI:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.04.003] [PMID]

Yen, C. F., Lin, H. C., Wang, P. W., Ko, C. H., Lee, K. H., & Hsu, C. Y., et al. (2016). Heroin craving and its correlations with clinical outcome indicators in people with heroin dependence receiving methadone maintenance treatment. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 65, 50–56. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.10.001] [PMID]

Yen, C. N., Wang, C. S., Wang, T. Y., Chen, H. F., & Chang, H. C. (2011). Quality of life and its correlates among heroin users in Taiwan. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 27(5), 177–183. [DOI:10.1016/j.kjms.2010.09.003] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Clinical Neuroscience

Received: 2023/09/24 | Accepted: 2024/01/30 | Published: 2025/03/1

Received: 2023/09/24 | Accepted: 2024/01/30 | Published: 2025/03/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |