Volume 16, Issue 5 (September & October 2025)

BCN 2025, 16(5): 869-878 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khadivi M, Ahmadzadeh Amiri A, Moghadam N, Ahmadzadeh Amiri A, Eslamian M, Zarei M, et al . A Report of Lumbar Disk Herniation Treatment Outcomes: Percutaneous Laser Disk Decompression vs Open Microdiscectomy. BCN 2025; 16 (5) :869-878

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2472-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2472-en.html

Masoud Khadivi1

, Ali Ahmadzadeh Amiri2

, Ali Ahmadzadeh Amiri2

, Navid Moghadam3

, Navid Moghadam3

, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri2

, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri2

, Mohammad Eslamian1

, Mohammad Eslamian1

, Mohammad Zarei4

, Mohammad Zarei4

, Mersad Moosavi3

, Mersad Moosavi3

, Milad Shafizadeh1

, Milad Shafizadeh1

, Alireza Borghei5

, Alireza Borghei5

, Ramin Kordi3

, Ramin Kordi3

, Mohsen Rostami *3

, Mohsen Rostami *3

, Ali Ahmadzadeh Amiri2

, Ali Ahmadzadeh Amiri2

, Navid Moghadam3

, Navid Moghadam3

, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri2

, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri2

, Mohammad Eslamian1

, Mohammad Eslamian1

, Mohammad Zarei4

, Mohammad Zarei4

, Mersad Moosavi3

, Mersad Moosavi3

, Milad Shafizadeh1

, Milad Shafizadeh1

, Alireza Borghei5

, Alireza Borghei5

, Ramin Kordi3

, Ramin Kordi3

, Mohsen Rostami *3

, Mohsen Rostami *3

1- Department of Neurosurgery, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Sports Medicine Research Center, Neuroscience Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Sports Medicine Research Center, Neuroscience Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Spine Center of Excellence, Yas Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Orthopedics, Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Neurosurgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Unites States.

2- Sports Medicine Research Center, Neuroscience Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Sports Medicine Research Center, Neuroscience Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. & Spine Center of Excellence, Yas Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Orthopedics, Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Neurosurgery, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Unites States.

Keywords: Lumbar spine, Percutaneous laser disk decompression (PLDD), Microdiscectomy, Protruded lumbar disk herniation, Disk pathologies

Full-Text [PDF 973 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

Introduction

Lumbar disk herniation (LDH) is one of the most common pathologies leading to radiculopathy. It has been reported that most LDHs occur at the L4-L5 or L5-S1 levels (Amin et al., 2017; Manchikanti et al., 2014). With aging, the production of proteoglycans in the spinal disk reduces, leading to disk dehydration and collapse. Consequently, the annulus fibrosus undergoes strain and tear, resulting in nucleus pulposus herniation. On the other hand, applying a heavy biomechanical axial force or inappropriate spinal kinetics can also lead to the extrusion of disk materials (Schoenfeld & Weiner, 2010). LDH is twice as prevalent in males compared to females and often occurs in the third to fifth decade of life (Fjeld, 2019).

Parallel to open microdiscectomy, which is the gold standard intervention for LDH (Sørlie et al., 2016), minimally invasive techniques such as percutaneous laser disk decompression (PLDD) have recently gained further attention (Ren et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2009). PLDD is believed to be effective in reducing intradiscal pressure through the thermal destruction of intradiscal material, thereby leading to indirect relief of nerve root compression, which is speculated to alleviate discogenic pain (Choy, 1996; Gangi et al., 1998; Chiarotto et al., 2016). Less invasion of soft tissue structures, faster recovery, and shorter hospital stays are some of the clinical advantages of PLDD compared to conventional methods. In addition, PLDD can be performed in an awake status, which further facilitates its application in patients with concurrent comorbidities (van den Akker-van Marle, 2017). Although Botsford (1994) argued that PLDD is more effective in patients with protruded (versus extruded) herniated disks, some reports have shown the effectiveness of PLDD in treating other types of herniated disks (Choy, 2001).

On the other hand, spine surgeons often select patients for open microdiscectomy or PLDD based on the intensity of their clinical symptoms, their neurologic status, and the morphology and location of the pathologic disk as seen in imaging studies (Choy, 1995). Although it has been reported that, compared to open discectomy, PLDD correlates with shorter operative time, less blood loss, and no further complications (Ali et al., 2013), long-term studies have shown no superiority of PLDD over open microdiscectomy regarding the clinical or radiological outcomes (Kreiner et al., 2014; Heider et al., 2017). Moreover, the cost-effectiveness of PLDD is another factor affecting its global acceptance among surgeons (van den Akker-van Marle, 2017).

Reviewing the literature, data are scarce on the clinical role of PLDD in the treatment of patients with LDH. In the current study, we retrospectively reviewed the short- and mid-term outcomes of patients who underwent PLDD and compared these results with those of an age- and sex-matched group of patients who underwent conventional open microdiscectomy.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective case series, we gathered outcome data for patients who underwent LDH intervention between 2017 and 2020 at Yas Hospital Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Patients

Patients diagnosed with LDH with severe refractory pain for at least 6 to 8 weeks were eligible to be included in the study. The diagnosis was made based on the clinical evaluations and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. According to the guidelines of our center, patients with chronic yet less severe protruded disks, as indicated by imaging (Figure 1) and clinical presentations, were referred for PLDD, while those with a protruded disk accompanied by any neurologic compromise were assigned to conventional surgery. All patients with a history of an extruded disk, previous vertebral surgeries, cauda equina syndrome (CES), bone disorders, generalized bulging disk, neurologic disorders (including movement disorders, urinary and fecal incontinence), pregnancy, any coagulopathy disease, and a reduction in disk height of more than 50% were excluded.

Besides, since coping with the complications of any intervention is relatively subjective and heavily depends on the physical and mental capacity of each patient, the final decision to assign patients into open microsurgery or PLDD was made based on a surgeon-patient meeting.

Interventions

All conventional microdiscectomy surgeries were done with the patient in a prone position and under general anesthesia. In this regard, the senior author incised the skin along the midline and employed a unilateral approach for muscle and soft tissue dissection. In this regard, after subperiosteal muscle dissection and exposure of the lamina, drilling of the lower part of the lamina and the base of the spinous process with minimum resection of the ipsilateral facet joint was done. To overcome the narrow field of view of the surgery and lighting in the surgical field, we used a surgical microscope, and under its visualization, the base of the spinous process was further resected. This maneuver provided an adequate view of the ligamentum flavum from its superior to the inferior pole, where it binds to bony elements. After precise removal of the flavum ligament, thecal sac and nerve roots were retracted medially. The herniated disk was completely removed, and decompression of the thecal sac and nerve roots was achieved. Finally, the wound was closed in separate layers.

According to the standard technique, PLDD was performed using fluoroscopy guidance and under local anesthesia (Hashemi et al., 2020). The patients were positioned prone, and using a posterolateral approach, a 500-µ fiber was placed into the disk space parallel to the inferior endplate. Laser energy of up to 2000 J was delivered to the disk, and the interventionist confirmed the vaporization of the disk’s water content.

Expert spine surgeon-interventionists performed both procedures, utilizing extensive experience in minimally invasive spine procedures. Additionally, no specific conservative protocol was recommended to either group after the intervention.

Outcome measures

In this study, multiple validated parameters were used to evaluate clinical outcomes. Baseline outcome parameters were recorded before surgery, and questionnaires were completed at two follow-up sessions following the interventions: at 2 and 6 months post-operation. The pain intensity was measured using a visual analog scale (VAS), which ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable). Additionally, patients were asked to complete a validated version of the 36-item short form health survey (SF-36) to report their quality of life (QoL) (Montazeri et al., 2005). The SF-36 measures the physical and social status of patients in eight domains. It ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating lower disability. Furthermore, as the Oswestry disability index (ODI) is one of the most principal tools in assessing spinal disability, we used the validated version of the ODI to obtain information about patients’ daily functional status (Mousavi et al., 2006). The score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of disability.

Statistical methods

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the variables. Baseline data were compared between the two treatment groups using the chi-square test, the independent sample t test, or the Mann-Whitney test, as applicable. The outcome measures were also assessed using a repeated-measures analysis of variance. The scores were presented as Mean±SD. Analyses were carried out using SPSS software, version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 165 patients (104 females and 61 males) were enrolled in this study, with a mean age of 52.1±15 years. Notably, 63% of the patients were females. Ninety patients (54.5%) with LDH underwent conventional open microdiscectomy, and the remaining 75 patients underwent PLDD. The demographic and surgical characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 1.

According to Table 1, 78 patients (47.3%) were diagnosed with an LDH at the level of L4-L5. The mean duration (in days) of suffering from severe symptoms before surgery was lower in the open discectomy group; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.12). We observed intra- and post-operative complications in 6 patients. In the PLDD group, 1 patient (1.3%) experienced temporary paresis of the lower limb, and 1(1.3%) had a wet tap during the intervention. In the open discectomy group, 1 patient (1.1%) had cerebrospinal fluid leak, 1(1.1%) had deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and 2(2.2%) suffered from wound infections during the post-operative course. The intra-group and inter-group comparisons of the outcome measurements are shown in Table 2.

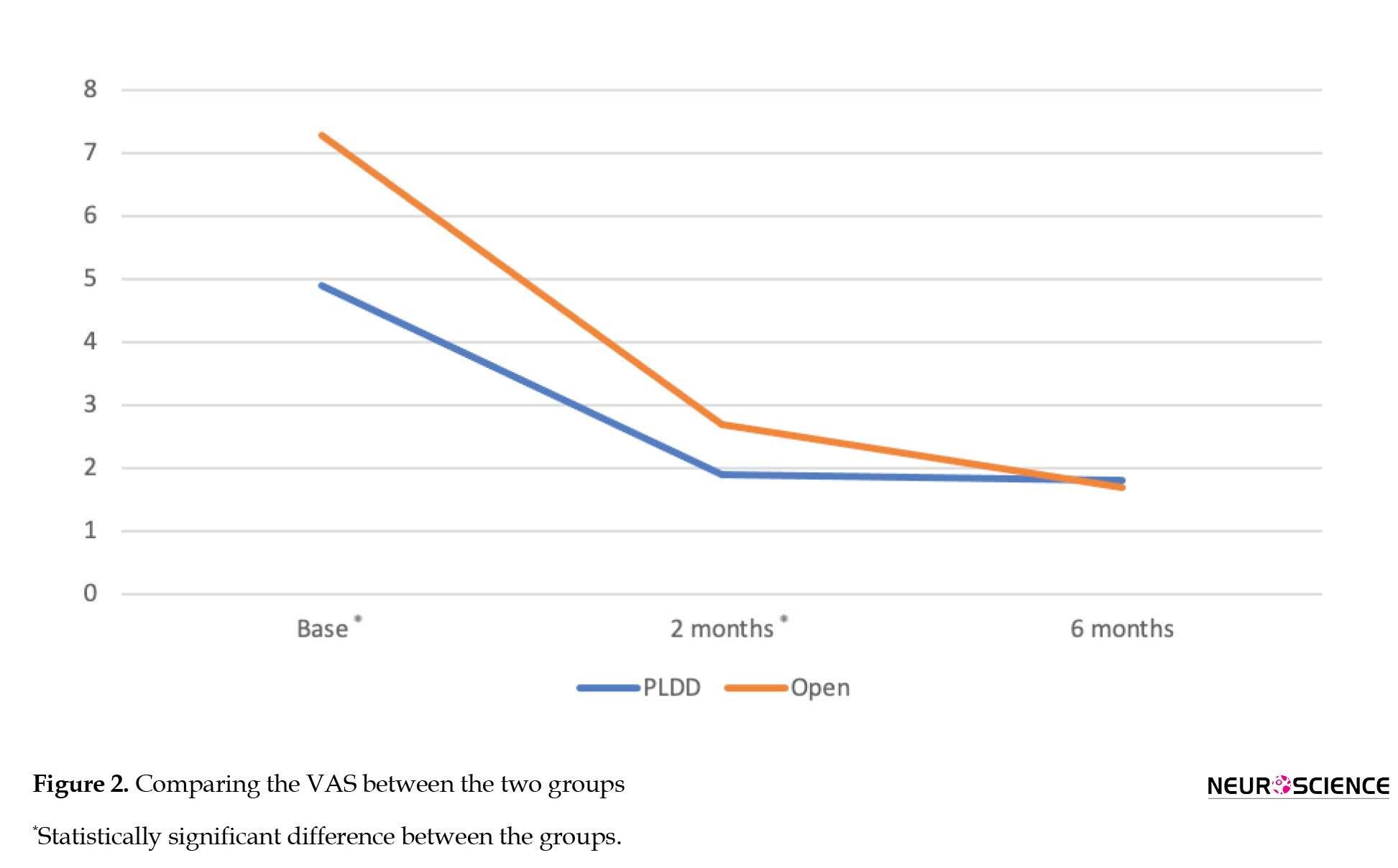

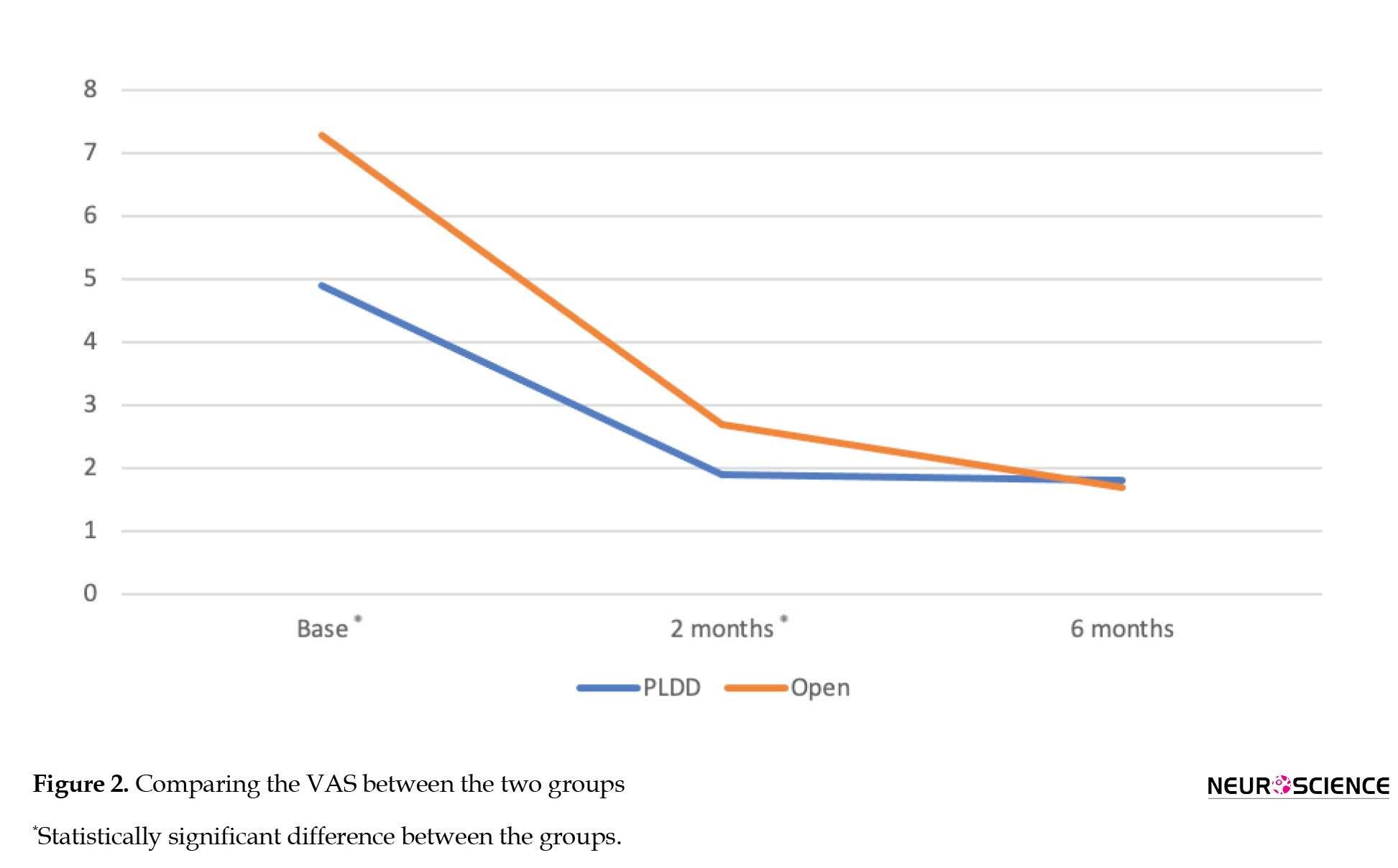

According to Table 2 and Figure 2, the baseline pain intensity was significantly lower among patients in the PLDD group (P<0.001). The mean VAS level has significantly decreased during the course of our study in both the PLDD and open discectomy groups (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). At the final follow-up, there was no statistically significant difference in the VAS level between the study groups.

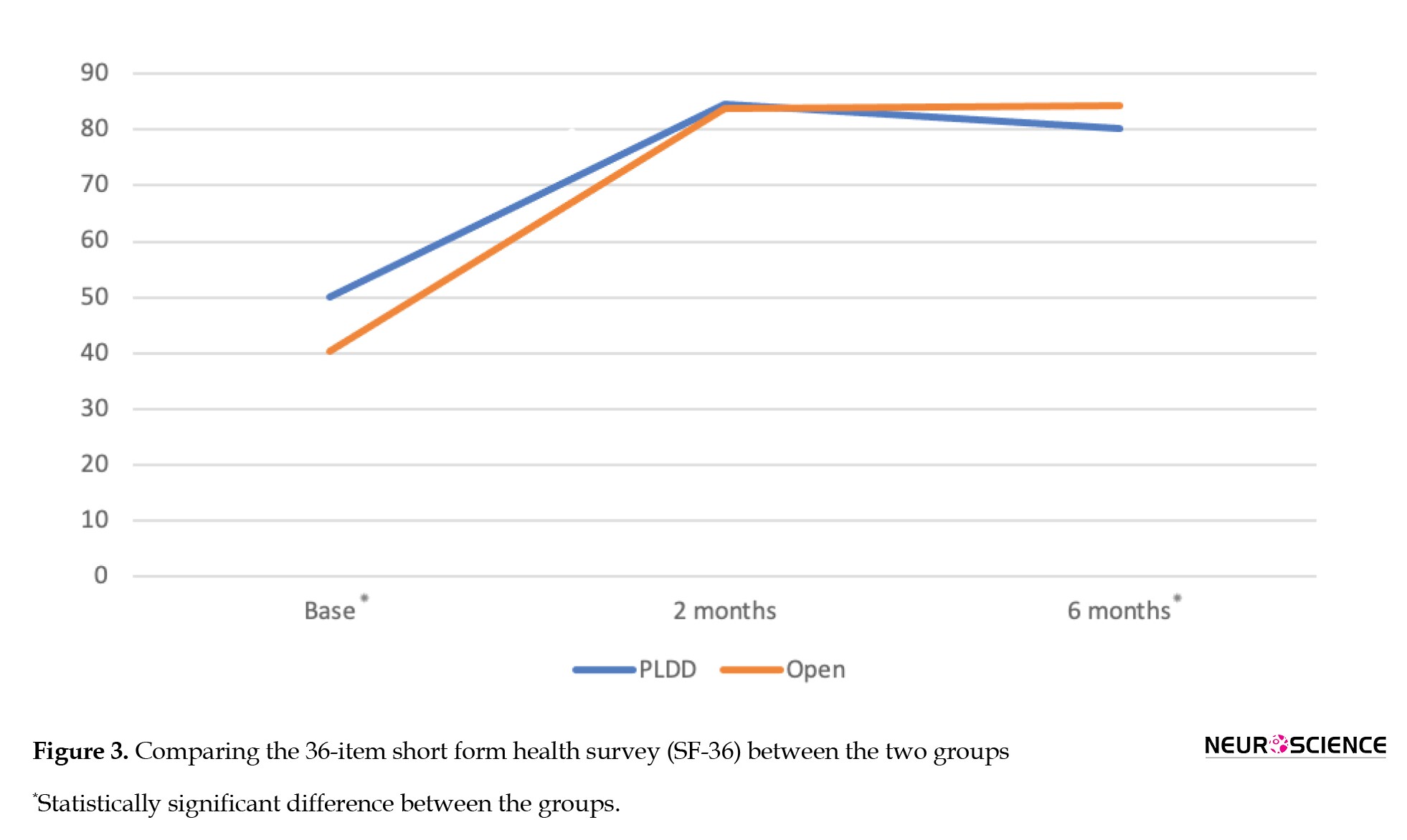

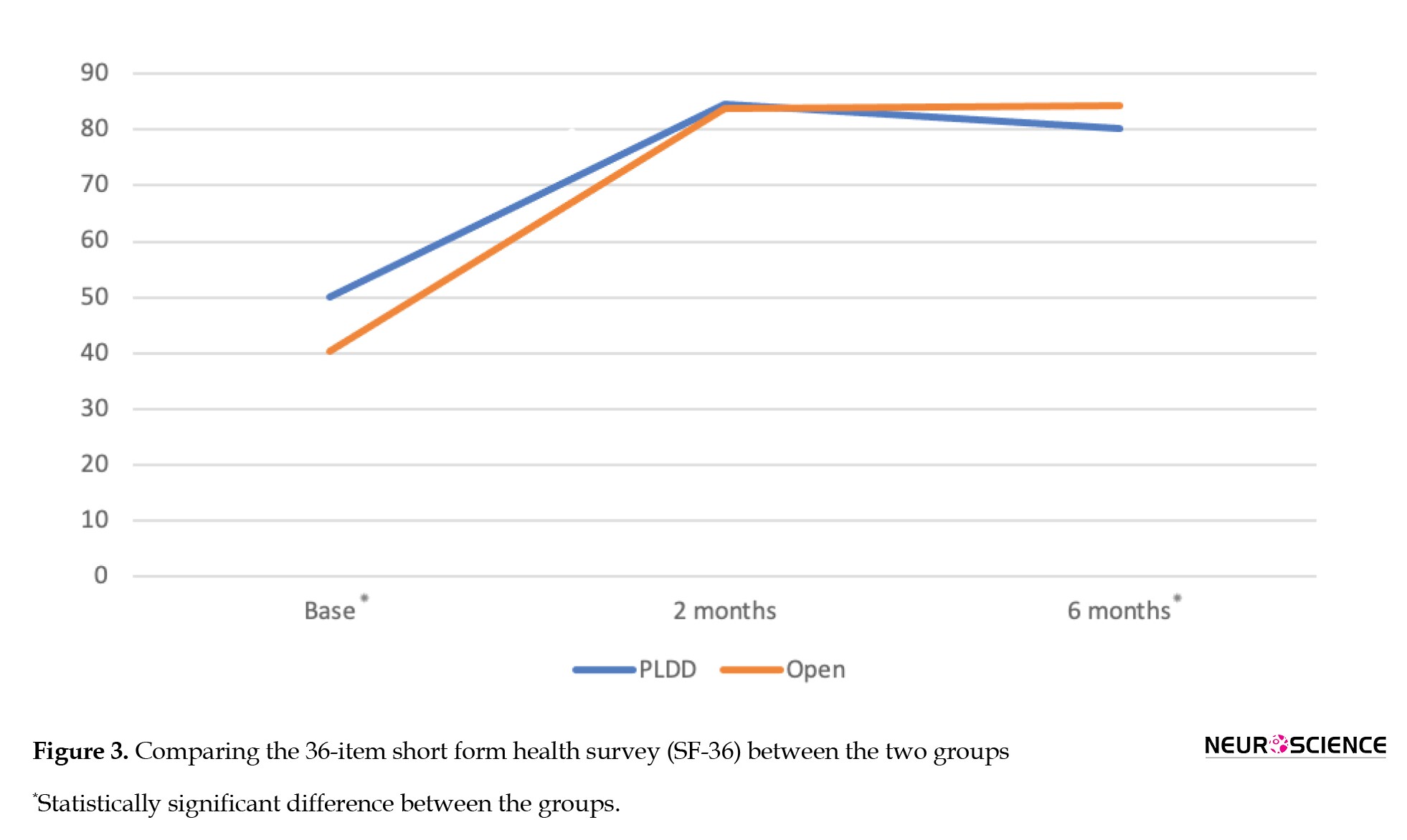

Our findings showed that the baseline QoL was significantly lower among those who underwent open surgery compared to the PLDD group (Figure 3). The score of SF-36 of the patients in both groups significantly improved over the 6-month follow-up of the study (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). The inter-group analysis showed no significant difference in the SF-36 score at 2 months post-operation between the groups (P=0.353). However, the mean SF-36 score of the open discectomy group was significantly higher than that of the PLDD group at 6 months postoperatively (P=0.001).

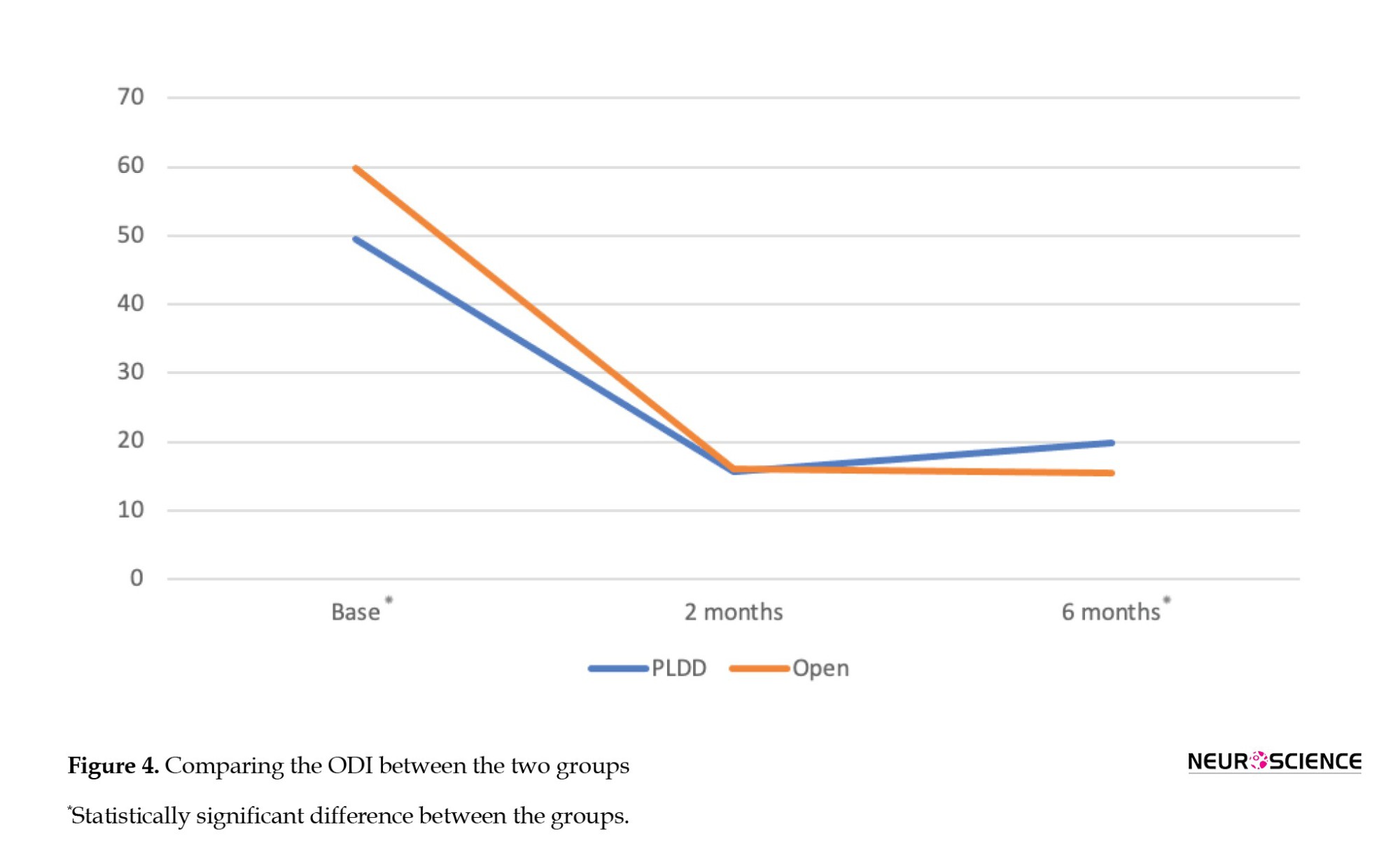

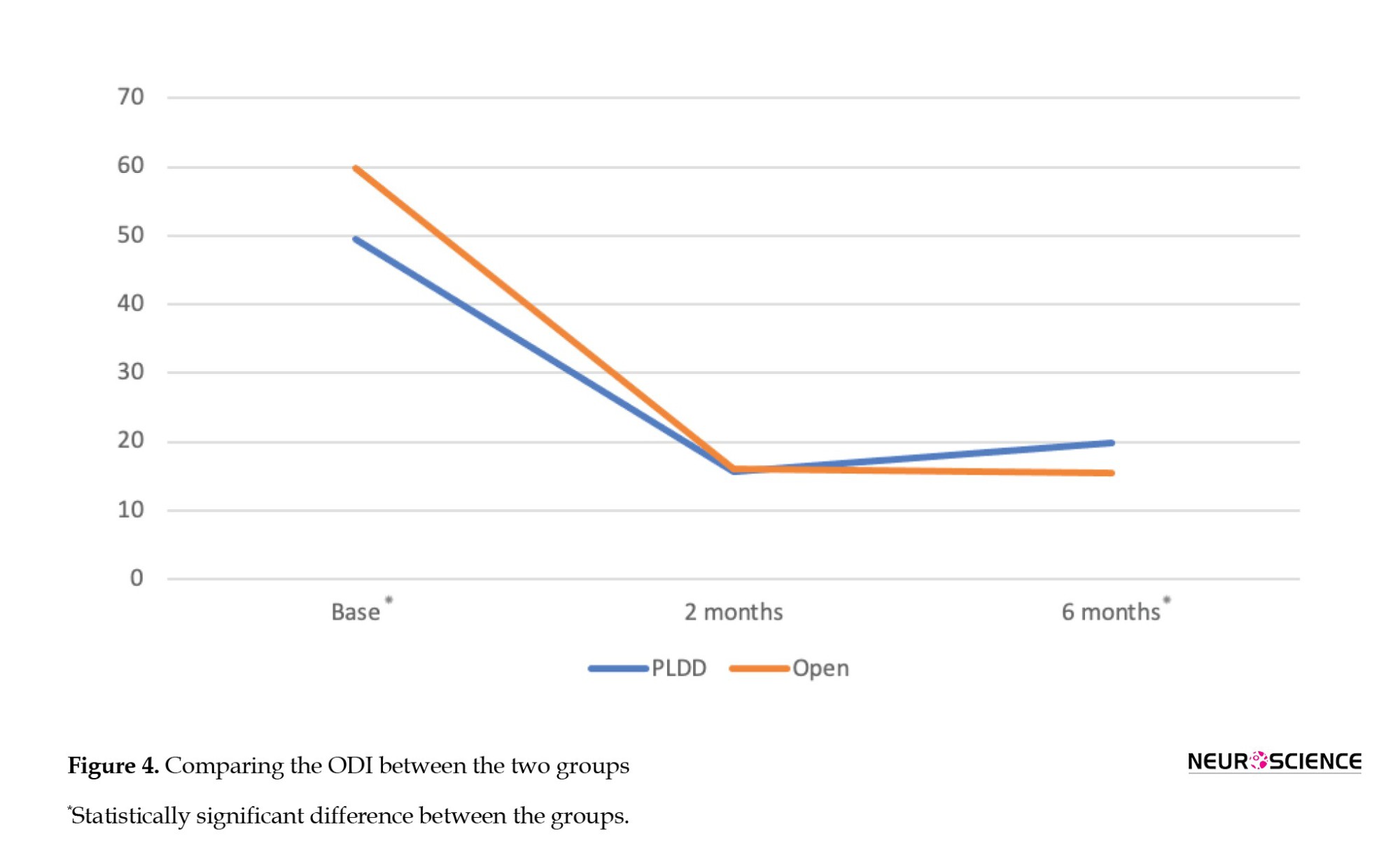

At baseline, the functional ability of patients in the surgical group was significantly lower than that of the PLDD group (P<0.001, Table 2). In both groups, the ODI scores significantly decreased from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). At 2 months post-operation, the inter-group analysis revealed no significant difference in ODI scores between the groups (P=0.50). However, the mean ODI score of the patients who underwent open discectomy was significantly lower than that of the PLDD group at 6 months follow-up (P=0.001, Figure 4).

Discussion

The evolution of various minimally invasive spinal surgeries has provided more feasible choices for both patients and surgeons (Singh et al, 2015). As an alternative to open discectomy, PLDD is a competent technique (McMillan et al., 2004; Tassi et al., 2004) and is now the treatment of choice for many surgeons.

In the current study, we retrospectively reported and compared the outcomes of patients with single-level protruded disks who underwent two different interventions over a 6-month period. The results showed that the clinical outcomes of both interventions are satisfactory and comparable. Our results also showed a low rate of complications for both procedures.

Based on the guidelines of our institute, cases with more severe presentations are assigned to the open discectomy surgery. Although Brouwer et al. (2017) argued that PLDD might be more effective among those with acute or subacute symptoms, Peul et al. (2007) reported that a longer duration of symptoms is a risk factor for poor clinical outcomes among those who undergo open microdiscectomy surgery. Therefore, subjects suffering from more severe pain intensity in a shorter timeframe were assigned to the open discectomy group by the surgeons.

Patients in both groups exhibited a significant decline in pain severity during the study, as measured by the VAS. In the open microdiscectomy group, pain intensity decreased at both 2-month and 6-month follow-ups. However, in the PLDD group, there was no significant improvement between 2- and 6-month follow-ups. Therefore, it could be argued that PLDD might decrease pain severity in the short term and have a less significant impact on pain intensity in longer follow-ups. These findings are not in accordance with the previous study (Brouwer et al., 2017), which has reported slightly lower VAS measures in the surgery group after 8 weeks and 26 weeks.

We also measured the QoL of the subjects at baseline, 2 months, and 6 months post-procedure using the SF-36 questionnaire. At the 2-month follow-up, both techniques achieved relatively similar results. Nevertheless, we observed a decline in the SF-36 score of the PLDD group at the 6-month follow-up, which was statistically significant compared to that of the open discectomy group. Our results, in line with those of a previous study (Brouwer et al., 2017), suggest that PLDD may have a more pronounced impact on the QoL of LDH patients in the short term.

The disability caused by the LDH was assessed using the ODI, and the results revealed a successful decline in the index in both groups. Our study showed that, although the mean level score of the ODI was relatively similar at the 2-month follow-up in both groups, PLDD failed to reduce disability severity further at the 6-month follow-up. This finding could again demonstrate that decreasing the disability is more eminent in the short term for PLDD. These findings are consistent with a previous study (Brouwer et al., 2017), which measured disability using the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire at 8 weeks and 26 weeks. Although the main clinical outcome measures differ, the more efficient short-term results in the PLDD group of our study are consistent with those reported in a study conducted by Ren et al. (2017), which revealed that LDH patients showed significant improvement in a short time after undergoing PLDD.

In summary, our study demonstrated that patients in the PLDD group achieve a better outcome in VAS at 2 months compared to the open group; however, the final outcomes in SF-36 and ODI measures are statistically significant between the two groups, indicating the superiority of open surgery compared to PLDD. This finding can be further highlighted considering that patients in the open surgery group have more severe symptoms at baseline compared to those who underwent PLDD.

The mechanism of pain reduction in microsurgery and PLDD may differ. Laser irradiation reduces a small amount of nucleus pulposus in the pathologic disc by vaporization, resulting in an immediate decrease in intradiscal pressure and withdrawal of disk compression on the nerve root (Choy et al., 1995). Additionally, PLDD reduces the inflammatory chemicals produced from the degenerative discs by laser heat generation (Saifuddin et al., 1999). Therefore, these mechanisms can make PLDD an acceptable method for treating small, hydrated, protruded discs with higher intradiscal pressure. On the other hand, microsurgery targets the mechanical compression of the bulged disc fragment, regardless of its size. Following resection of the fragment and irrigation, the inflammatory condition subsides (Brouwer et al., 2015).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our report demonstrated that although patients with more severe symptoms underwent open microsurgery, both methods significantly improved clinical outcomes, including pain intensity, QoL, and functional status, in patients with protruded disk herniation.

Study limitations

Due to the retrospective nature of our report, this study has several limitations, including a lack of post-operative morphological assessment of the disk and surrounding structures via MRI, a relatively small sample size, and a short timeframe for patient follow-up. More importantly, the non-randomized patient selection method, which leads to baseline imbalance and a disparity in the proportion of the groups, is another notable limitation of our study. Therefore, further prospective studies and controlled trials are needed to compare the clinical outcomes of these interventions more precisely.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Given that the interventions were conducted at a academic and research centre, written informed consent were obtained from all patients as all of them are included in our registry. All ethical principles are considered in this article’s designed and conduct based on the declaration of Helsinki. The purpose of the interventions and its implementation stages, alternative treatments, the outcome of choosing non-intervention, and possible side effects were discussed and documented. The option to leave this therapeutic intervention at any time, as well as the possibility of the use of anonymized patient data, including clinical and investigational outcomes were clearly communicated with the patients. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, given that neither the authors nor the patients were aware of conceptualization of this particular study at the time of therapeutic intervention, no ethical consideration is to be considered in this research beyond what is already discussed above. The registry was approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code IR.TUMS.NI.REC.1401.095).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Masoud Khadivi, Navid Moghadam, Mohammad Eslamian, Mohammad Zarei, Mersad Moosavi, Ramin Kordi, and Mohsen Rostami; Methodology: Masoud Khadivi, Mohammad Eslamian, Mohammad Zarei, Mersad Moosavi, Milad Shafizadeh, Alireza Borghei, and Mohsen Rostami; Data analysis: Ahmadzadeh Amiri, Navid Moghadam, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri, and Alireza Borghei; Validation and resources:Masoud Khadivi, Navid Moghadam, Mohammad Eslamian, Mohammad Zarei, Mersad Moosavi, Milad Shafizadeh, Alireza Borghei, Ramin Kordi, and Mohsen Rostami; Visualization and writing the original draft: Ali Ahmadzadeh Amiri, Navid Moghadam, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri, and Mohsen Rostami; Review and editing: Masoud Khadivi, Ahmadzadeh Amiri, Navid Moghadam, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri, and Ramin Kordi; Mohsen Rostami; Supervision: Navid Moghadam, Ramin Kordi, and Mohsen Rostami; Project Administration: Ahmadzadeh Amiri, Navid Moghadam, Ramin Kordi, and Mohsen Rostami.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the staff in the Sports Medicine Research Center and Clinics, Neuroscience Institute, Spine Center of Excellence, Yas Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, contribution in gathering the patients’ records.

References

Lumbar disk herniation (LDH) is one of the most common pathologies leading to radiculopathy. It has been reported that most LDHs occur at the L4-L5 or L5-S1 levels (Amin et al., 2017; Manchikanti et al., 2014). With aging, the production of proteoglycans in the spinal disk reduces, leading to disk dehydration and collapse. Consequently, the annulus fibrosus undergoes strain and tear, resulting in nucleus pulposus herniation. On the other hand, applying a heavy biomechanical axial force or inappropriate spinal kinetics can also lead to the extrusion of disk materials (Schoenfeld & Weiner, 2010). LDH is twice as prevalent in males compared to females and often occurs in the third to fifth decade of life (Fjeld, 2019).

Parallel to open microdiscectomy, which is the gold standard intervention for LDH (Sørlie et al., 2016), minimally invasive techniques such as percutaneous laser disk decompression (PLDD) have recently gained further attention (Ren et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2009). PLDD is believed to be effective in reducing intradiscal pressure through the thermal destruction of intradiscal material, thereby leading to indirect relief of nerve root compression, which is speculated to alleviate discogenic pain (Choy, 1996; Gangi et al., 1998; Chiarotto et al., 2016). Less invasion of soft tissue structures, faster recovery, and shorter hospital stays are some of the clinical advantages of PLDD compared to conventional methods. In addition, PLDD can be performed in an awake status, which further facilitates its application in patients with concurrent comorbidities (van den Akker-van Marle, 2017). Although Botsford (1994) argued that PLDD is more effective in patients with protruded (versus extruded) herniated disks, some reports have shown the effectiveness of PLDD in treating other types of herniated disks (Choy, 2001).

On the other hand, spine surgeons often select patients for open microdiscectomy or PLDD based on the intensity of their clinical symptoms, their neurologic status, and the morphology and location of the pathologic disk as seen in imaging studies (Choy, 1995). Although it has been reported that, compared to open discectomy, PLDD correlates with shorter operative time, less blood loss, and no further complications (Ali et al., 2013), long-term studies have shown no superiority of PLDD over open microdiscectomy regarding the clinical or radiological outcomes (Kreiner et al., 2014; Heider et al., 2017). Moreover, the cost-effectiveness of PLDD is another factor affecting its global acceptance among surgeons (van den Akker-van Marle, 2017).

Reviewing the literature, data are scarce on the clinical role of PLDD in the treatment of patients with LDH. In the current study, we retrospectively reviewed the short- and mid-term outcomes of patients who underwent PLDD and compared these results with those of an age- and sex-matched group of patients who underwent conventional open microdiscectomy.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective case series, we gathered outcome data for patients who underwent LDH intervention between 2017 and 2020 at Yas Hospital Complex, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Patients

Patients diagnosed with LDH with severe refractory pain for at least 6 to 8 weeks were eligible to be included in the study. The diagnosis was made based on the clinical evaluations and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings. According to the guidelines of our center, patients with chronic yet less severe protruded disks, as indicated by imaging (Figure 1) and clinical presentations, were referred for PLDD, while those with a protruded disk accompanied by any neurologic compromise were assigned to conventional surgery. All patients with a history of an extruded disk, previous vertebral surgeries, cauda equina syndrome (CES), bone disorders, generalized bulging disk, neurologic disorders (including movement disorders, urinary and fecal incontinence), pregnancy, any coagulopathy disease, and a reduction in disk height of more than 50% were excluded.

Besides, since coping with the complications of any intervention is relatively subjective and heavily depends on the physical and mental capacity of each patient, the final decision to assign patients into open microsurgery or PLDD was made based on a surgeon-patient meeting.

Interventions

All conventional microdiscectomy surgeries were done with the patient in a prone position and under general anesthesia. In this regard, the senior author incised the skin along the midline and employed a unilateral approach for muscle and soft tissue dissection. In this regard, after subperiosteal muscle dissection and exposure of the lamina, drilling of the lower part of the lamina and the base of the spinous process with minimum resection of the ipsilateral facet joint was done. To overcome the narrow field of view of the surgery and lighting in the surgical field, we used a surgical microscope, and under its visualization, the base of the spinous process was further resected. This maneuver provided an adequate view of the ligamentum flavum from its superior to the inferior pole, where it binds to bony elements. After precise removal of the flavum ligament, thecal sac and nerve roots were retracted medially. The herniated disk was completely removed, and decompression of the thecal sac and nerve roots was achieved. Finally, the wound was closed in separate layers.

According to the standard technique, PLDD was performed using fluoroscopy guidance and under local anesthesia (Hashemi et al., 2020). The patients were positioned prone, and using a posterolateral approach, a 500-µ fiber was placed into the disk space parallel to the inferior endplate. Laser energy of up to 2000 J was delivered to the disk, and the interventionist confirmed the vaporization of the disk’s water content.

Expert spine surgeon-interventionists performed both procedures, utilizing extensive experience in minimally invasive spine procedures. Additionally, no specific conservative protocol was recommended to either group after the intervention.

Outcome measures

In this study, multiple validated parameters were used to evaluate clinical outcomes. Baseline outcome parameters were recorded before surgery, and questionnaires were completed at two follow-up sessions following the interventions: at 2 and 6 months post-operation. The pain intensity was measured using a visual analog scale (VAS), which ranged from 0 (no pain) to 10 (the worst pain imaginable). Additionally, patients were asked to complete a validated version of the 36-item short form health survey (SF-36) to report their quality of life (QoL) (Montazeri et al., 2005). The SF-36 measures the physical and social status of patients in eight domains. It ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating lower disability. Furthermore, as the Oswestry disability index (ODI) is one of the most principal tools in assessing spinal disability, we used the validated version of the ODI to obtain information about patients’ daily functional status (Mousavi et al., 2006). The score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of disability.

Statistical methods

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the variables. Baseline data were compared between the two treatment groups using the chi-square test, the independent sample t test, or the Mann-Whitney test, as applicable. The outcome measures were also assessed using a repeated-measures analysis of variance. The scores were presented as Mean±SD. Analyses were carried out using SPSS software, version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 165 patients (104 females and 61 males) were enrolled in this study, with a mean age of 52.1±15 years. Notably, 63% of the patients were females. Ninety patients (54.5%) with LDH underwent conventional open microdiscectomy, and the remaining 75 patients underwent PLDD. The demographic and surgical characteristics of the subjects are summarized in Table 1.

According to Table 1, 78 patients (47.3%) were diagnosed with an LDH at the level of L4-L5. The mean duration (in days) of suffering from severe symptoms before surgery was lower in the open discectomy group; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.12). We observed intra- and post-operative complications in 6 patients. In the PLDD group, 1 patient (1.3%) experienced temporary paresis of the lower limb, and 1(1.3%) had a wet tap during the intervention. In the open discectomy group, 1 patient (1.1%) had cerebrospinal fluid leak, 1(1.1%) had deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and 2(2.2%) suffered from wound infections during the post-operative course. The intra-group and inter-group comparisons of the outcome measurements are shown in Table 2.

According to Table 2 and Figure 2, the baseline pain intensity was significantly lower among patients in the PLDD group (P<0.001). The mean VAS level has significantly decreased during the course of our study in both the PLDD and open discectomy groups (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). At the final follow-up, there was no statistically significant difference in the VAS level between the study groups.

Our findings showed that the baseline QoL was significantly lower among those who underwent open surgery compared to the PLDD group (Figure 3). The score of SF-36 of the patients in both groups significantly improved over the 6-month follow-up of the study (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). The inter-group analysis showed no significant difference in the SF-36 score at 2 months post-operation between the groups (P=0.353). However, the mean SF-36 score of the open discectomy group was significantly higher than that of the PLDD group at 6 months postoperatively (P=0.001).

At baseline, the functional ability of patients in the surgical group was significantly lower than that of the PLDD group (P<0.001, Table 2). In both groups, the ODI scores significantly decreased from pre-operation to 6 months post-operation (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). At 2 months post-operation, the inter-group analysis revealed no significant difference in ODI scores between the groups (P=0.50). However, the mean ODI score of the patients who underwent open discectomy was significantly lower than that of the PLDD group at 6 months follow-up (P=0.001, Figure 4).

Discussion

The evolution of various minimally invasive spinal surgeries has provided more feasible choices for both patients and surgeons (Singh et al, 2015). As an alternative to open discectomy, PLDD is a competent technique (McMillan et al., 2004; Tassi et al., 2004) and is now the treatment of choice for many surgeons.

In the current study, we retrospectively reported and compared the outcomes of patients with single-level protruded disks who underwent two different interventions over a 6-month period. The results showed that the clinical outcomes of both interventions are satisfactory and comparable. Our results also showed a low rate of complications for both procedures.

Based on the guidelines of our institute, cases with more severe presentations are assigned to the open discectomy surgery. Although Brouwer et al. (2017) argued that PLDD might be more effective among those with acute or subacute symptoms, Peul et al. (2007) reported that a longer duration of symptoms is a risk factor for poor clinical outcomes among those who undergo open microdiscectomy surgery. Therefore, subjects suffering from more severe pain intensity in a shorter timeframe were assigned to the open discectomy group by the surgeons.

Patients in both groups exhibited a significant decline in pain severity during the study, as measured by the VAS. In the open microdiscectomy group, pain intensity decreased at both 2-month and 6-month follow-ups. However, in the PLDD group, there was no significant improvement between 2- and 6-month follow-ups. Therefore, it could be argued that PLDD might decrease pain severity in the short term and have a less significant impact on pain intensity in longer follow-ups. These findings are not in accordance with the previous study (Brouwer et al., 2017), which has reported slightly lower VAS measures in the surgery group after 8 weeks and 26 weeks.

We also measured the QoL of the subjects at baseline, 2 months, and 6 months post-procedure using the SF-36 questionnaire. At the 2-month follow-up, both techniques achieved relatively similar results. Nevertheless, we observed a decline in the SF-36 score of the PLDD group at the 6-month follow-up, which was statistically significant compared to that of the open discectomy group. Our results, in line with those of a previous study (Brouwer et al., 2017), suggest that PLDD may have a more pronounced impact on the QoL of LDH patients in the short term.

The disability caused by the LDH was assessed using the ODI, and the results revealed a successful decline in the index in both groups. Our study showed that, although the mean level score of the ODI was relatively similar at the 2-month follow-up in both groups, PLDD failed to reduce disability severity further at the 6-month follow-up. This finding could again demonstrate that decreasing the disability is more eminent in the short term for PLDD. These findings are consistent with a previous study (Brouwer et al., 2017), which measured disability using the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire at 8 weeks and 26 weeks. Although the main clinical outcome measures differ, the more efficient short-term results in the PLDD group of our study are consistent with those reported in a study conducted by Ren et al. (2017), which revealed that LDH patients showed significant improvement in a short time after undergoing PLDD.

In summary, our study demonstrated that patients in the PLDD group achieve a better outcome in VAS at 2 months compared to the open group; however, the final outcomes in SF-36 and ODI measures are statistically significant between the two groups, indicating the superiority of open surgery compared to PLDD. This finding can be further highlighted considering that patients in the open surgery group have more severe symptoms at baseline compared to those who underwent PLDD.

The mechanism of pain reduction in microsurgery and PLDD may differ. Laser irradiation reduces a small amount of nucleus pulposus in the pathologic disc by vaporization, resulting in an immediate decrease in intradiscal pressure and withdrawal of disk compression on the nerve root (Choy et al., 1995). Additionally, PLDD reduces the inflammatory chemicals produced from the degenerative discs by laser heat generation (Saifuddin et al., 1999). Therefore, these mechanisms can make PLDD an acceptable method for treating small, hydrated, protruded discs with higher intradiscal pressure. On the other hand, microsurgery targets the mechanical compression of the bulged disc fragment, regardless of its size. Following resection of the fragment and irrigation, the inflammatory condition subsides (Brouwer et al., 2015).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our report demonstrated that although patients with more severe symptoms underwent open microsurgery, both methods significantly improved clinical outcomes, including pain intensity, QoL, and functional status, in patients with protruded disk herniation.

Study limitations

Due to the retrospective nature of our report, this study has several limitations, including a lack of post-operative morphological assessment of the disk and surrounding structures via MRI, a relatively small sample size, and a short timeframe for patient follow-up. More importantly, the non-randomized patient selection method, which leads to baseline imbalance and a disparity in the proportion of the groups, is another notable limitation of our study. Therefore, further prospective studies and controlled trials are needed to compare the clinical outcomes of these interventions more precisely.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Given that the interventions were conducted at a academic and research centre, written informed consent were obtained from all patients as all of them are included in our registry. All ethical principles are considered in this article’s designed and conduct based on the declaration of Helsinki. The purpose of the interventions and its implementation stages, alternative treatments, the outcome of choosing non-intervention, and possible side effects were discussed and documented. The option to leave this therapeutic intervention at any time, as well as the possibility of the use of anonymized patient data, including clinical and investigational outcomes were clearly communicated with the patients. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, given that neither the authors nor the patients were aware of conceptualization of this particular study at the time of therapeutic intervention, no ethical consideration is to be considered in this research beyond what is already discussed above. The registry was approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code IR.TUMS.NI.REC.1401.095).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Masoud Khadivi, Navid Moghadam, Mohammad Eslamian, Mohammad Zarei, Mersad Moosavi, Ramin Kordi, and Mohsen Rostami; Methodology: Masoud Khadivi, Mohammad Eslamian, Mohammad Zarei, Mersad Moosavi, Milad Shafizadeh, Alireza Borghei, and Mohsen Rostami; Data analysis: Ahmadzadeh Amiri, Navid Moghadam, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri, and Alireza Borghei; Validation and resources:Masoud Khadivi, Navid Moghadam, Mohammad Eslamian, Mohammad Zarei, Mersad Moosavi, Milad Shafizadeh, Alireza Borghei, Ramin Kordi, and Mohsen Rostami; Visualization and writing the original draft: Ali Ahmadzadeh Amiri, Navid Moghadam, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri, and Mohsen Rostami; Review and editing: Masoud Khadivi, Ahmadzadeh Amiri, Navid Moghadam, Amir Ahmadzadeh Amiri, and Ramin Kordi; Mohsen Rostami; Supervision: Navid Moghadam, Ramin Kordi, and Mohsen Rostami; Project Administration: Ahmadzadeh Amiri, Navid Moghadam, Ramin Kordi, and Mohsen Rostami.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the staff in the Sports Medicine Research Center and Clinics, Neuroscience Institute, Spine Center of Excellence, Yas Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, contribution in gathering the patients’ records.

References

Ali, Y. M., Sarwar, J. M., Hossain, M. S., Sarker, M. C., Kayes, M. N., & Rahman, M. M. (2013). Percutaneous laser disc decompression: A minimally invasive procedure for the treatment of intervertebral disc prolapse–the Bangladesh perspective/Perkutane Laser-Diskusdekompression: Ein minimal-invasives Verfahren zur Behandlung von Bandscheibenvorfall–Ein Erfahrungsbericht aus Bangladesch. Photonics & Lasers in Medicine, 2(3), 249-254. [DOI:10.1515/plm-2012-0036]

Amin, R. M., Andrade, N. S., & Neuman, B. J. (2017). Lumbar disc herniation. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 10(4), 507–516.[DOI:10.1007/s12178-017-9441-4] [PMID]

Botsford J. A. (1994). Radiological considerations: Patient selection for percutaneous laser disc decompression. Journal of Clinical Laser Medicine & Surgery, 12(5), 255–259. [DOI:10.1089/clm.1994.12.255] [PMID]

Brouwer, P. A., Brand, R., van den Akker-van Marle, M. E., Jacobs, W. C., Schenk, B., & van den Berg-Huijsmans, A. A., et al. (2017). Percutaneous laser disc decompression versus conventional microdiscectomy for patients with sciatica: Two-year results of a randomised controlled trial. Interventional Neuroradiology: Journal of Peritherapeutic Neuroradiology, Surgical Procedures and Related Neurosciences, 23(3), 313–324. [DOI:10.1177/1591019917699981] [PMID]

Brouwer, P. A., Brand, R., van den Akker-van Marle, M. E., Jacobs, W. C., Schenk, B., & van den Berg-Huijsmans, A. A., et al. (2015). Percutaneous laser disc decompression versus conventional microdiscectomy in sciatica: A randomized controlled trial. The Spine Journal: Official Journal of the North American Spine Society, 15(5), 857–865. [DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2015.01.020] [PMID]

Chiarotto, A., Maxwell, L. J., Terwee, C. B., Wells, G. A., Tugwell, P., & Ostelo, R. W. (2016). Roland-morris disability questionnaire and oswestry disability index: which has better measurement properties for measuring physical functioning in nonspecific low back pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Physical Therapy, 96(10), 1620–1637. [DOI:10.2522/ptj.20150420] [PMID]

Choy D. S. (1995). Percutaneous laser disc decompression (PLDD): 352 cases with an 8 1/2-year follow-up. Journal of Clinical Laser Medicine & Surgery, 13(1), 17–21.[DOI:10.1089/clm.1995.13.17] [PMID]

Choy D. S. (1996). Rapid correction of neurologic deficits by percutaneous laser disc decompression (PLDD). Journal of Clinical Laser Medicine & Surgery, 14(1), 13–15.[DOI:10.1089/clm.1996.14.13] [PMID]

Choy, D. S. (2001). Response of extruded intervertebral herniated discs to percutaneous laser disc decompression. Journal of Clinical Laser Medicine & Surgery, 19(1), 15–20. [DOI:10.1089/104454701750066893] [PMID]

Choy, D. S., & Altman, P. (1995). Fall of intradiscal pressure with laser ablation. Journal of Clinical Laser Medicine & Surgery, 13(3), 149–151. [DOI:10.1089/clm.1995.13.149] [PMID]

Fjeld, O. R., Grøvle, L., Helgeland, J., Småstuen, M. C., Solberg, T. K., & Zwart, J. A., et al. (2019). Complications, reoperations, readmissions, and length of hospital stay in 34 639 surgical cases of lumbar disc herniation. The Bone & Joint Journal, 101-B(4), 470–477. [DOI:10.1302/0301-620X.101B4.BJJ-2018-1184.R1] [PMID]

Gangi, A., Dietemann, J. L., Mortazavi, R., Pfleger, D., Kauff, C., & Roy, C. (1998). CT-guided interventional procedures for pain management in the lumbosacral spine. Radiographics: A review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc, 18(3), 621–633. [DOI:10.1148/radiographics.18.3.9599387] [PMID]

Hashemi, M., Dadkhah, P., Taheri, M., Katibeh, P., & Asadi, S. (2020). Effectiveness of intradiscal injection of radiopaque gelified ethanol (DiscoGel®) versus percutaneous laser disc decompression in patients with chronic radicular low back pain. The Korean Journal of Pain, 33(1), 66–72. [DOI:10.3344/kjp.2020.33.1.66] [PMID]

Heider, F. C., & Mayer, H. M. (2017). [Surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation (German)]. Operative Orthopadie und Traumatologie, 29(1), 59–85. [DOI:10.1007/s00064-016-0467-3] [PMID]

Kreiner, D. S., Hwang, S. W., Easa, J. E., Resnick, D. K., Baisden, J. L., & Bess, S., et al. (2014). An evidence-based clinical guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy. The Spine Journal: Official Journal of the North American Spine Society, 14(1), 180–191. [DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.003] [PMID]

Manchikanti, L., Singh, V., Falco, F. J., Benyamin, R. M., & Hirsch, J. A. (2014). Epidemiology of low back pain in adults. Neuromodulation: Journal of the International Neuromodulation Society, 17 (Suppl 2), 3–10. [DOI:10.1111/ner.12018] [PMID]

McMillan, M. R., Patterson, P. A., & Parker, V. (2004). Percutaneous laser disc decompression for the treatment of discogenic lumbar pain and sciatica: A preliminary report with 3-month follow-up in a general pain clinic population. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery, 22(5), 434–438. [DOI:10.1089/pho.2004.22.434] [PMID]

Montazeri, A., Goshtasebi, A., Vahdaninia, M., & Gandek, B. (2005). The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 14(3), 875–882. [DOI:10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5] [PMID]

Mousavi, S. J., Parnianpour, M., Mehdian, H., Montazeri, A., & Mobini, B. (2006). The Oswestry disability index, the Roland-morris disability questionnaire, and the Quebec back pain disability scale: Translation and validation studies of the Iranian versions. Spine, 31(14), E454–E459.[DOI:10.1097/01.brs.0000222141.61424.f7] [PMID]

Peul, W. C., van Houwelingen, H. C., van den Hout, W. B., Brand, R., Eekhof, J. A., & Tans, J. T., et al. (2007). Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. The New England Journal of Medicine, 356(22), 2245–2256 [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa064039] [PMID]

Ren, L., Guo, H., Zhang, T., Han, Z., Zhang, L., & Zeng, Y. (2013). Efficacy evaluation of percutaneous laser disc decompression in the treatment of lumbar disc herniation. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery, 31(4), 174–178. [DOI:10.1089/pho.2012.3402] [PMID]

Saifuddin, A., Mitchell, R., & Taylor, B. A. (1999). Extradural inflammation associated with annular tears: demonstration with gadolinium-enhanced lumbar spine MRI. European Spine Journal: Official Publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 8(1), 34–39. [DOI:10.1007/s005860050124] [PMID]

Schoenfeld, A. J., & Weiner, B. K. (2010). Treatment of lumbar disc herniation: Evidence-based practice. International Journal of General Medicine, 3, 209–214. [DOI:10.2147/IJGM.S12270] [PMID]

Singh, V., Manchikanti, L., Benyamin, R. M., Helm, S., & Hirsch, J. A. (2009). Percutaneous lumbar laser disc decompression: A systematic review of current evidence. Pain Physician, 12(3), 573–588. [DOI:10.36076/ppj.2009/12/573] [PMID]

Singh, K., Ledet, E., & Carl, A. (2005). Intradiscal therapy: A review of current treatment modalities. Spine, 30(17 Suppl), S20–S26. [DOI:10.1097/01.brs.0000175181.28730.ab] [PMID]

Sørlie, A., Gulati, S., Giannadakis, C., Carlsen, S. M., Salvesen, Ø., & Nygaard, Ø. P., et al. (2016). Open discectomy vs microdiscectomy for lumbar disc herniation - a protocol for a pragmatic comparative effectiveness study. F1000Research, 5, 2170. [DOI:10.12688/f1000research.9015.1] [PMID]

Tassi, G. P. (2004). Preliminary Italian experience of lumbar spine percutaneous laser disc decompression according to Choy's method. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery, 22(5), 439–441. [DOI:10.1089/pho.2004.22.439] [PMID]

van den Akker-van Marle, M. E., Brouwer, P. A., Brand, R., Koes, B., van den Hout, W. B., & van Buchem, M. A., et al. (2017). Percutaneous laser disc decompression versus microdiscectomy for sciatica: Cost utility analysis alongside a randomized controlled trial. Interventional Neuroradiology: Journal of Peritherapeutic Neuroradiology, Surgical Procedures and Related Neurosciences, 23(5), 538–545. [DOI:10.1177/1591019917710297] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Clinical Neuroscience

Received: 2024/05/14 | Accepted: 2024/09/21 | Published: 2025/09/1

Received: 2024/05/14 | Accepted: 2024/09/21 | Published: 2025/09/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |