Volume 16 - Special Issue on Cognitive Sciences

BCN 2025, 16 - Special Issue on Cognitive Sciences: 205-218 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mousavi S Z, Jalilevand N, Ashayeri H, Abolghasemi J. The Effects of the Persian Writing Treatment Protocol on Communication Skills in People With Aphasia After Stroke. BCN 2025; 16 (S1) :205-218

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2462-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2462-en.html

1- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Basic Sciences, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Basic Sciences, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 638 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

1. Introduction

Stroke is a focal neurological deficit that results from a localized disorder of cerebral circulation, and it is a significant cause of death and disability in industrialized countries (Wilson & Raghavan, 2018). It is expected that the number of stroke patients increase to 3.4 million between 2012 and 2030 because of lower mortality rate and the rising population age (Ovbiagele et al., 2013). This increase will be more pronounced in future decades (Feigin et al., 2017). Aphasia is one of the most severe post-stroke deficits, affecting one-third of acute stroke patients (Brady et al., 2016; Pollock et al., 2012). It is a general term that describes a range of acquired defects in language function following brain damage, usually affecting the left hemisphere. Aphasia can affect all receptive and expressive communication modalities, i.e. speech, comprehension, reading and writing, and gestures (Berthier & Aging, 2005; Schweizer & Macdonald, 2014).

Since the communication process is affected in people with aphasia (PWA), researchers have always been looking for treatments that can improve their quality of life (QoL). There are two major approaches to therapy. Impairment-based treatments target specific language sub-components; they enhance language functions, such as phonology, lexical semantics, or syntax, in structured therapy to reduce language impairment. The assumption is that doing so will also improve communication skills and, consequently, the QoL. Another approach is functional communication treatments, which target communication skills more directly and do not emphasize generalization in treating speech or language impairments. Also, more than focusing on impairment, functional treatment concentrates on removing environmental barriers to enhance the success of communication (Coppens, 2016).

In some cases, verbal language is severely impaired, and the PWA loses the ability to communicate through speech, so choosing an alternative or complementary approach seems necessary (Beeson et al., 2002). Among the communication ways, writing has almost the closest characteristics to verbal language, and written language can be the best way to communicate, exchange information, and meet needs. Besides being a substitute for speech, writing can also facilitate and improve the patient’s communication quality (Beeson et al., 2000; Beeson et al., 2010; Beeson et al., 2003). In general, written language is an important communication channel that is comparable to verbal language and does not depend on it (Coppens, 2016).

In the aphasia rehabilitation field, writing disorder has received less attention than other language modalities. Most treatments in these patients reported in different studies have focused on verbal language, and there are fewer studies on writing treatment (Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson et al., 2000; Beeson et al., 2010; Beeson et al., 2003). This gap does not underestimate the value of writing treatment in PWA. More recent studies have suggested the significance of writing in improving communication in PWA and reported the appropriate response of these patients to such treatment (Beeson et al., 2018; Clausen & Besson, 2003; Robson et al., 2001; Thiel et al., 2015; Thiel et al., 2016). Most of these studies have been performed as single and multiple case studies and have used writing treatment based on impairment-based writing therapies at the level of single words or sentences using lexical or phonological methods (Beeson et al., 2013; Beeson et al., 2018; Beeson et al., 2010; Thiel & Conroy, 2014). Two lexical-semantic protocols, i.e. anagram and copy treatment and copy and recall treatment designed by Beeson, were widely used in the writing treatment studies of patients with acquired writing disorder, and all of them have reported these treatments successfully in improving patients’ writing skills with an increase in their communication functions (Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson et al., 2000; Beeson et al., 2003; Beeson, 1999). Other studies have used phonological therapies alone or in combination with lexical therapy methods, and most have involved phoneme-to-grapheme conversion. Like lexical therapies, all phonological therapy studies have reported successful results in patients’ writing treatment (Beeson et al., 2018; Beeson et al., 2010; Thiel et al., 2016).

A general review of the literature concludes that writing treatment serves various purposes, including restoring writing skills, stimulating verbal language, or being an alternative to verbal language, especially for patients with limited speech for communication, and all of them are effective (Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson et al., 2000; Beeson et al., 2010; Beeson et al., 2003; Clausen & Besson, 2003; Coppens, 2016; Thiel et al., 2015; Thiel et al., 2016).

Since there is no comprehensive treatment for writing disorders in PWA in Iran, the primary purpose of this study was to design a writing treatment protocol appropriate to the Persian language with the principles of lexical-semantic therapy as a new approach besides the other applied clinical therapies used for PWA and to investigate the effects of writing treatment on improving the communication performance of PWA. The findings of the present study can provide a new perspective on the treatment of stroke patients with Persian-speaking aphasia. This designed treatment protocol can be used in treatment plans in the aphasia field to improve patients’ communication and QoL.

2. Materials and Methods

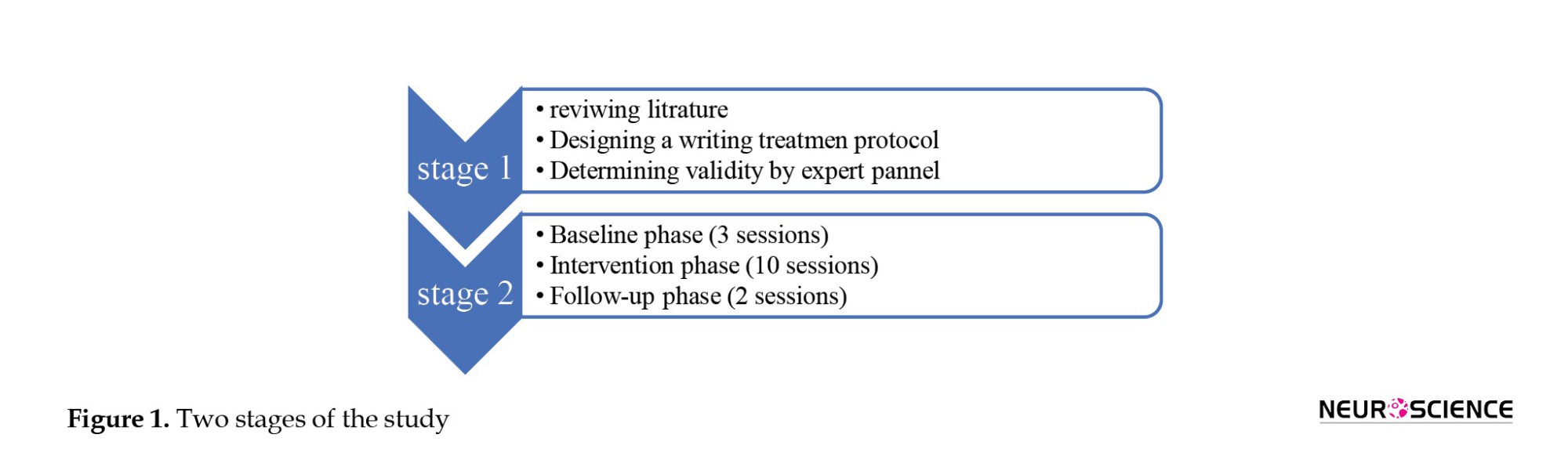

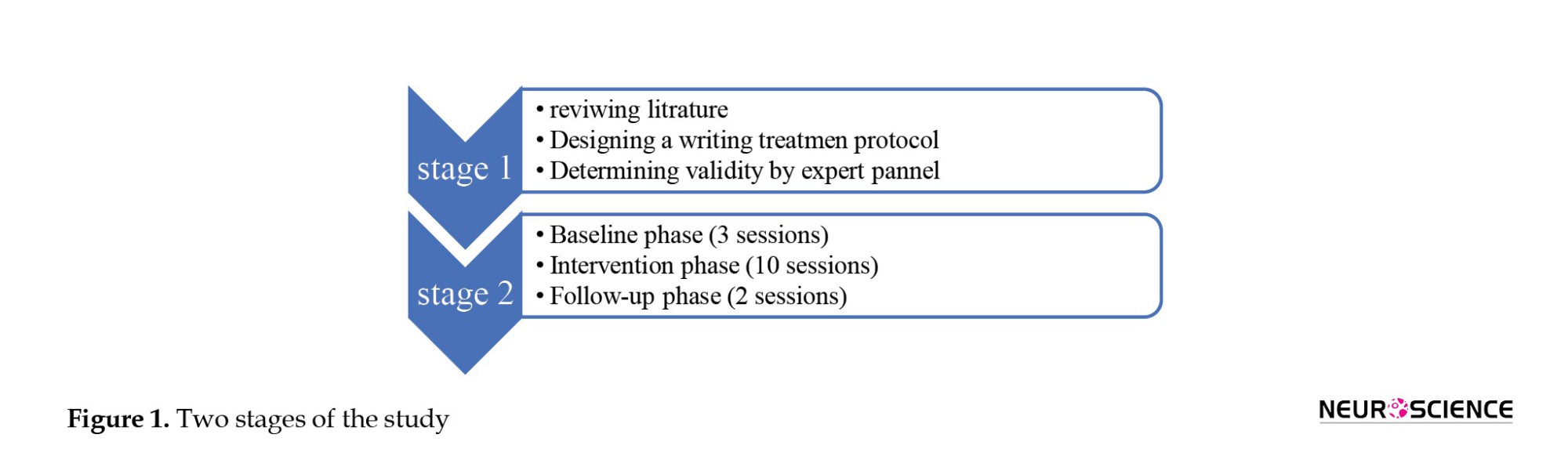

This study has two main stages. The first stage deals with developing a writing treatment protocol, and the second stage focuses on determining the effect of the developed protocol on PWA. These steps are described below.

The first stage: Developing a writing treatment protocol

This stage included an extensive literature review focusing on writing treatment in PWA, especially the lexical-semantic approach. It was modeled in designing a Persian writing treatment protocol. This approach involves arranging the component letters of the target word and using the bracketing approach for the patient’s failed attempts. In other words, the cues in the treatment step started with simple tasks and gradually became more difficult, and finally, repetitive copies of the correct form of the target word were made.

The steps in the writing treatment protocol were designed considering the characteristics of the Persian written language. Also, the bracketing approach was considered in these steps. The developed protocol included the following steps:

- Providing a picture of the target functional word and asking the PWA to write its name,

- Using semantic, phonological, and verbal repetition cues (in this order) to stimulate word retrieval if the patient cannot write the target word,

- Presenting the printed word syllables on the paper card (typed in size 92 with simple font) irregularly so that the PWA can retrieve the target word by arranging them,

- Arranging the printed letters of the word that are presented irregularly to the PWA,

- Presenting a few additional letters that included vowels and consonants on the cards, as well as different forms of letters related to a phoneme that were visually similar to the component letters of the target word, so that the PWA can select the correct letters from them and write the target word,

- In the last step, hiding all the writing patterns so that the patient retrieves the written word from memory and finally writes it independently.

In all the above steps, if the patient cannot write the target functional word, the therapist arranges the cards correctly to instruct the PWA to use them as a template. After the patient can write the word correctly, they should copy the correct pattern three times.

In this way, an initial version of the writing treatment protocol was developed with the short-term plan of writing the functional word correctly considered a list for training during treatment sessions using the writing treatment protocol. Also, the long-term goal was to communicate and request needs through writing.

To determine the validity of the developed protocol, its final version was made available to 10 experts in the field, including speech and language pathologists and linguists, to apply their comments by considering the study’s purpose and the target population. They were asked to comment on the appropriateness of the protocol and correctly prioritize the cueing hierarchy of the treatment protocol. Then, their answers and suggestions were analyzed and applied to the treatment protocol. The statistical methods used in this section included content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR).

The second stage: Evaluating the effectiveness of writing treatment in PWA using the developed protocol

The research in this section was a single-subject study with an ABA design. In such research, few subjects are studied at any time, and the changes resulting from the treatment program are evaluated in relation to the same subject, not in relation to other participants; that is, the participant plays both the role of the subject and the control. Regarding the nature of the single-subject study and the length of the evaluation and treatment process, 6 PWA were studied in this project, according to the inclusion criteria: Unilateral damage of the left hemisphere based on the brain imaging and neurologist diagnosis, deficit due to stroke, no previous history of stroke, no history of cognitive disorder based on mini-mental state examination (MMSE), no other neurological disorder such as Parkinson and Alzheimer, chronic stage, i.e. at least 6 months post-onset time, monolingualism, right-handedness, and no concomitant therapeutic intervention during the writing treatment.

First, according to the neurologist’s diagnosis and brain imaging report, the location of the lesion was determined, and brain damage in the left hemisphere due to stroke was confirmed. All of the subjects’ aphasia was classified as non-fluent. Lesions in the left perisylvian regions had caused it. Then, the intervention process was explained to PWA and their families for completing informed consent. Ethical issues were considered, including the following: All PWA participated voluntarily and were free to leave the study whenever they wanted; their information remained confidential, and the Committee of Iran University Medical Sciences approved the study.

A demographic questionnaire was completed for each PWA, including personal information and a medical history report. All PWA were evaluated through initial pre-treatment tests including Persian aphasia battery for assessing severity of aphasia in different aspects of language and also for differential diagnosis, the bedside version of Persian diagnostic aphasia battery (P-DAB-1) (Nilipour et al., 2014) for determining aphasia severity based on aphasia quotient (AQ), and the aphasia naming test (Nilipour, 2011) for clinical assessment of naming skills. The inclusion criteria included patients with aphasia who were in the chronic phase, had brain damage in the left hemisphere, were non-fluent, had limited speech for communication, were not receiving other speech therapy, and were willing to learn writing therapy.

Then, an ABA design was performed on each patient. First, the functional words of any participant were selected by consulting with the PWA and their families. These were the personal words that the PWA frequently used in daily life and were divided into 50 trained words into 10 sets of 5 words (which were treated 1 set during each treatment session based on a writing treatment protocol) and 50 untrained words (to evaluate the generalization of treatment to other words that were not treated). They were used at baseline and probes during treatment sessions to assess the maintenance and stability of scores after treatment in the follow-up phase.

The baseline phase was repeated for 3 consecutive weeks (1 session per week), and their results were plotted as a graph called the baseline diagram. After the baseline phase and stable writing performance of PWA, the intervention phase started using the developed writing treatment protocol. Furthermore, according to previous studies, the number of sessions and treatment intervention duration were the same for all subjects, and 10 sessions were performed twice a week for 1 hour (Beeson, 1999). At this phase, probes were carried out regularly at the end of each week, and both trained and untrained words were evaluated to determine the resulting changes and improvements. These results were drawn as a second graph beside the first diagram. In the third phase, 1 month after intervention sessions, all evaluations were carried out again (two sessions per week). The results were recorded in the diagram. This phase showed the generalization, stabilization, or possible changes in treatment. Ultimately, the Persian aphasia battery, P-DAB-1, and aphasia naming test were re-administered. These stages are shown in detail in Figure 1.

Statistical analysis

In this single-subject study, baseline, intervention, and follow-up diagrams were drawn for all the subjects. Visual analysis (stability and changes in within-condition and between-condition) and effect size indices like improvement rate difference (IRD), percentage of non-overlapping data (PND), and percentage of overlapping data (POD) were examined. In analyzing the results of the Persian aphasia battery, the aphasia naming test and P-DAB-1 test before and after treatment based on the developed writing treatment protocol, non-parametric Wilcoxon was used. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 22 at a 95% confidence level.

3. Results

The first stage of the study

An expert panel determined the content validity of the developed writing treatment protocol. Ten experts were provided with comments on each step of this protocol in three categories: Necessary, useful but not necessary, and not necessary. Then, CVR was determined. As in the Lawshe table, the CVR for all steps was greater than 0.62. This figure indicates that essential steps have been taken in this treatment protocol. To calculate CVI, the experts were asked to score the three criteria of relevance, simplicity, and clarity of the developed protocol steps based on a 4-point Likert scale (not relevant, somewhat relevant, quite relevant, and very relevant, in which 0 reflected no relevance between the mentioned items, and 4 indicated the most relevance). The CVI showed that the experts chose relevant and very relevant options for all the designed steps, and the CVI score was higher than 0.90, so it was appropriate.

The second stage of the study

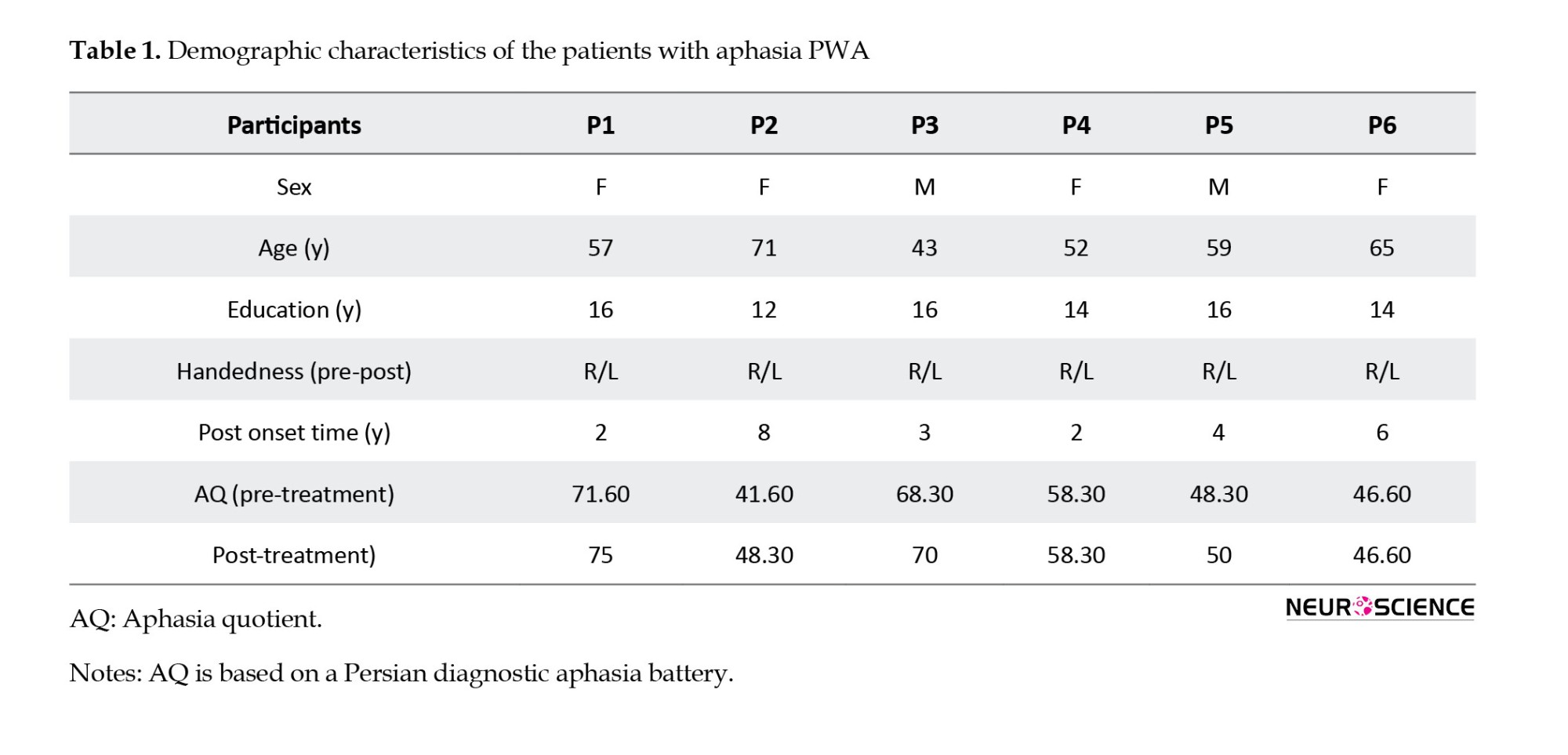

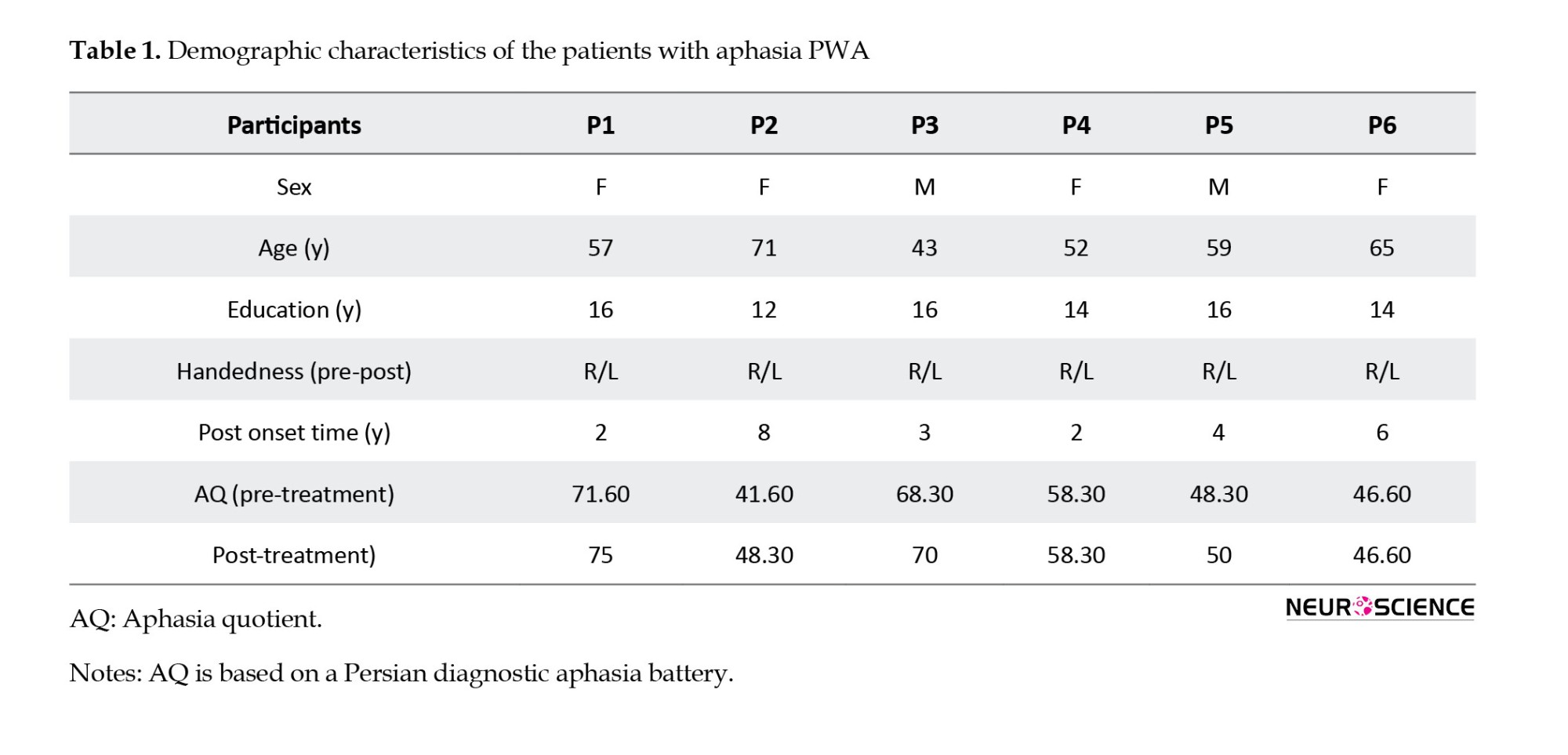

Six patients with aphasia following a stroke in the left hemisphere were studied, all of whom were right-handed before the stroke, but they used the left hand to write in this study because of right hemiplegia or paresis after the lesion. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

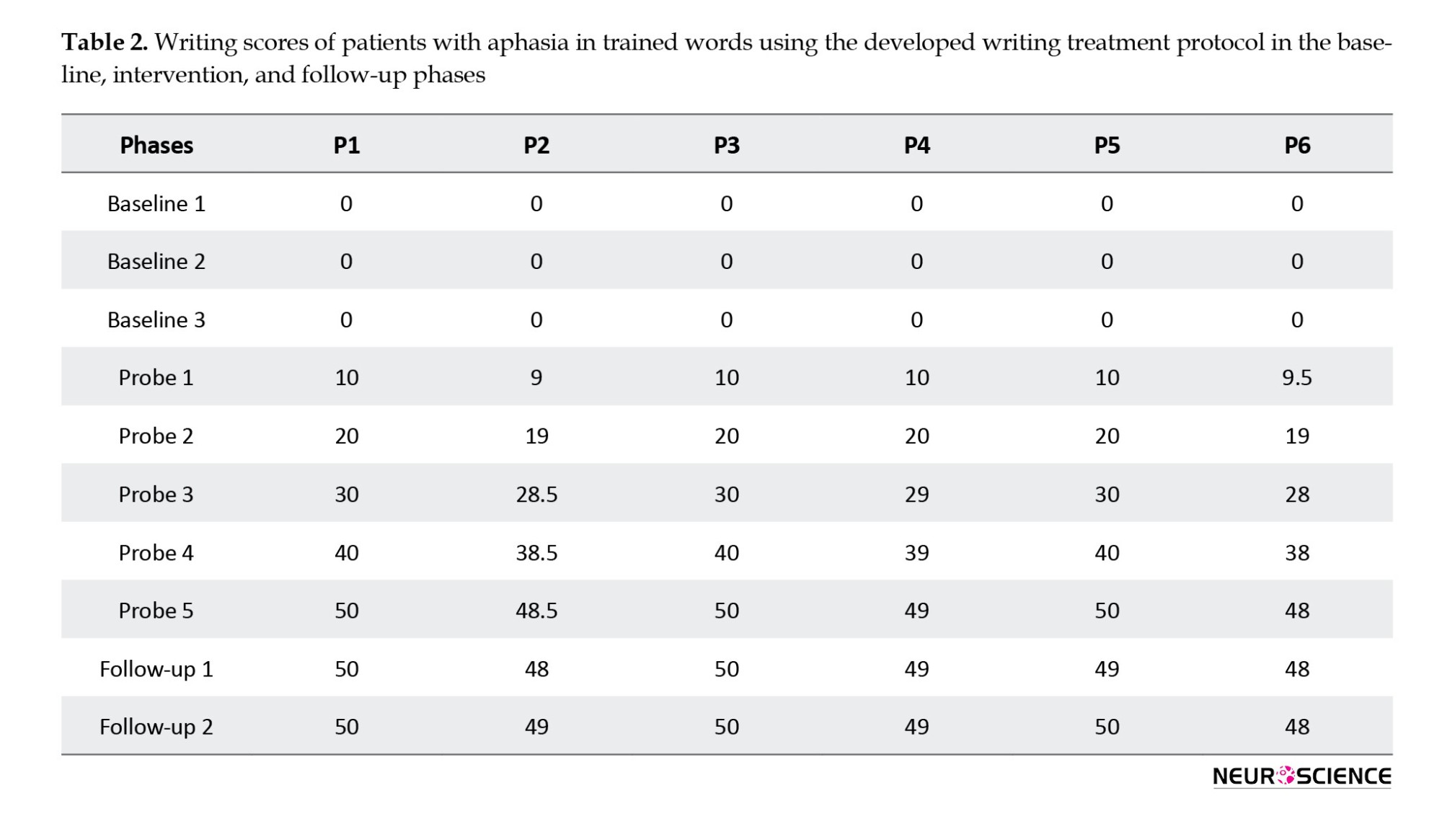

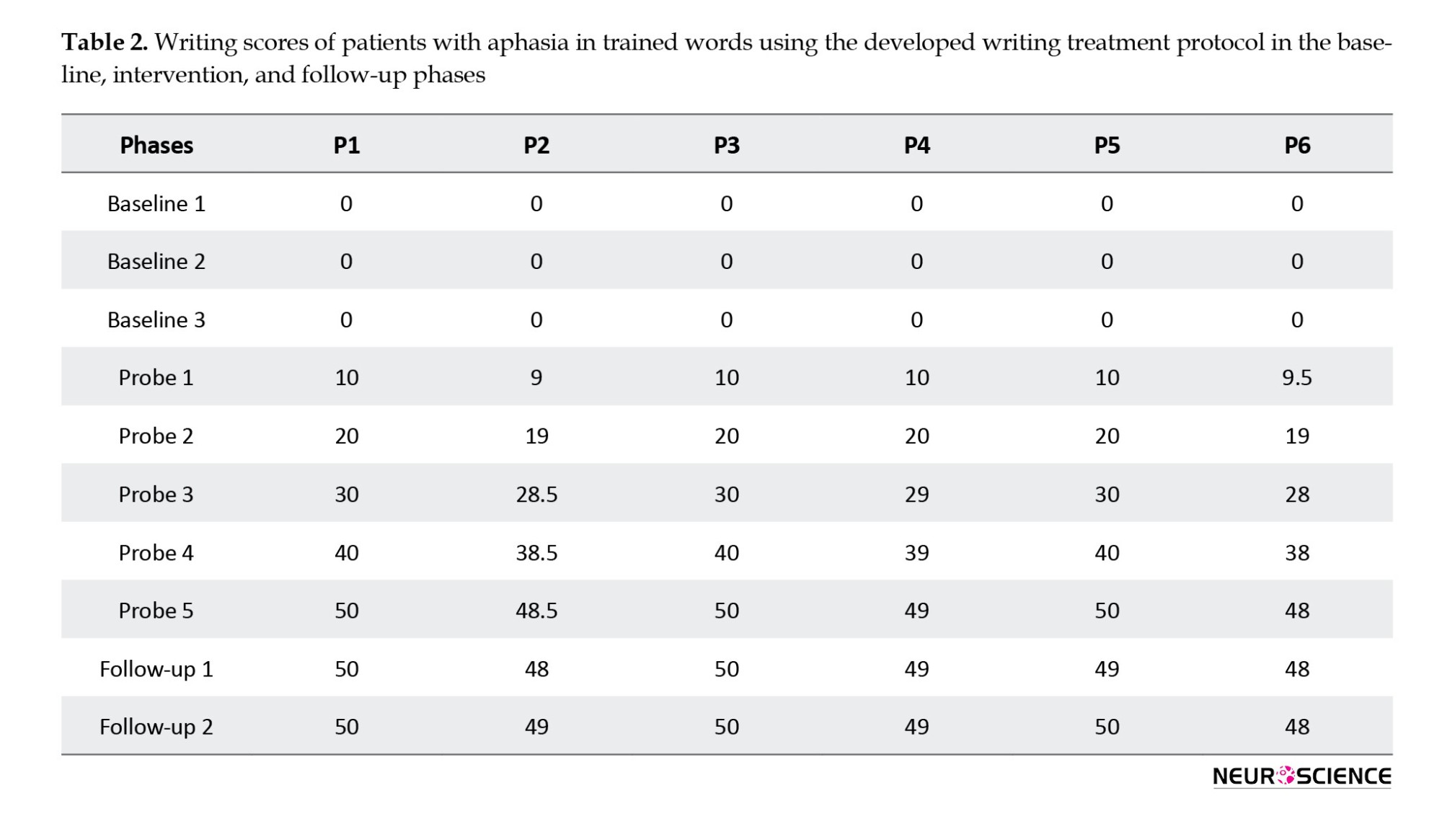

Several patients may participate in single-subject studies, but the data are analyzed separately for each participant, and the subject performance changes are scored in different phases during each session. The present study shows the effect of intervention in 50 trained words using the writing treatment protocol in the baseline phase, weekly probes, and follow-up in PWA in Table 2.

The pre-treatment results showed that before treatment, no person with aphasia could write even one of the selected functional words, which was shown in the baseline sessions (3 times) with zero scores. Initial evaluations before the starting treatment showed that among the 6 PWA, only two patients (1 and 3) were interested in re-learning writing performance. However, the other four patients did not try because of frustration and stated that they could not write words. However, interesting results were obtained for all PWA after starting the writing therapy session using the developed protocol. Higher scores per session showed improvement during the intervention. A noteworthy point is that the scores at the follow-up phase showed that this progress was consistent and did not decrease over time.

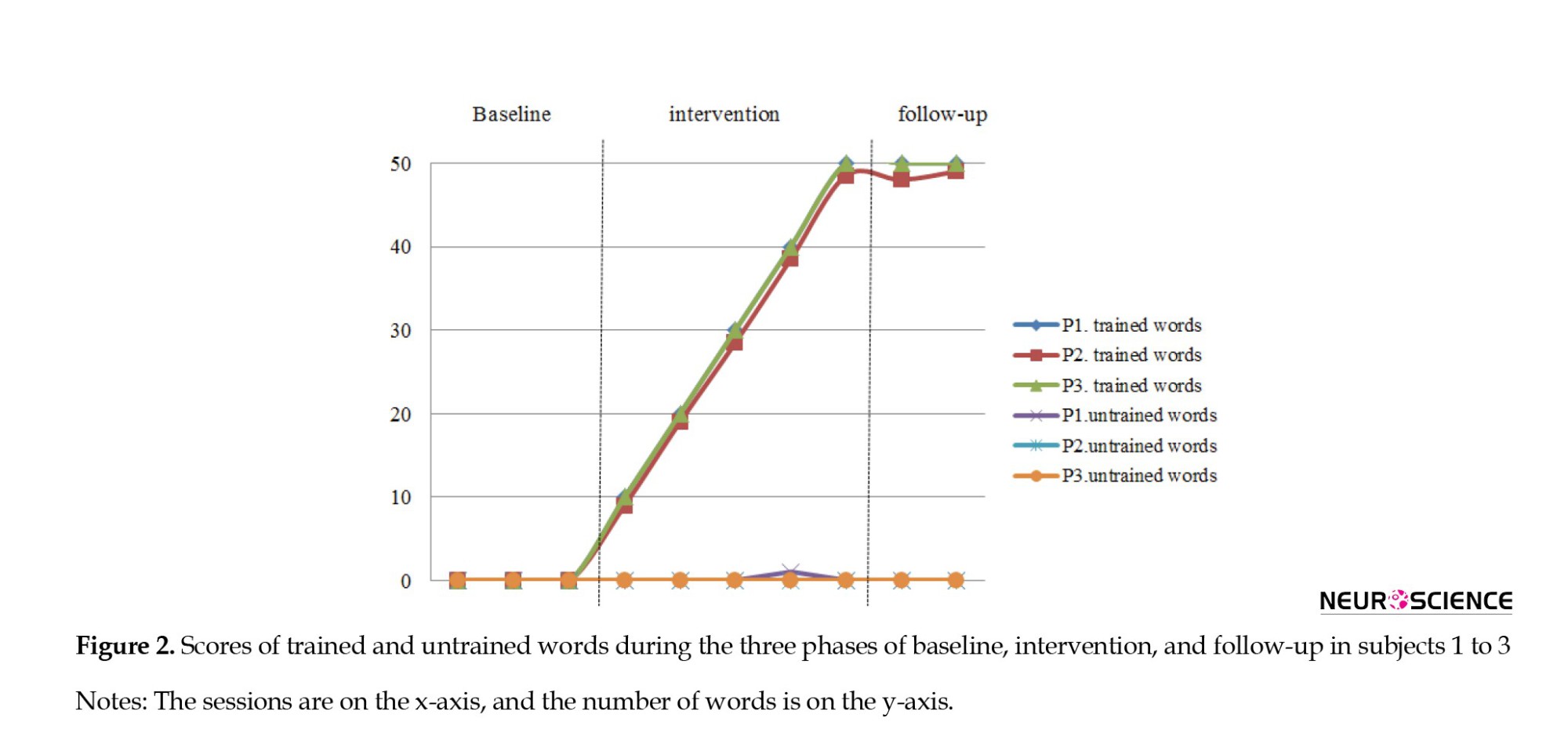

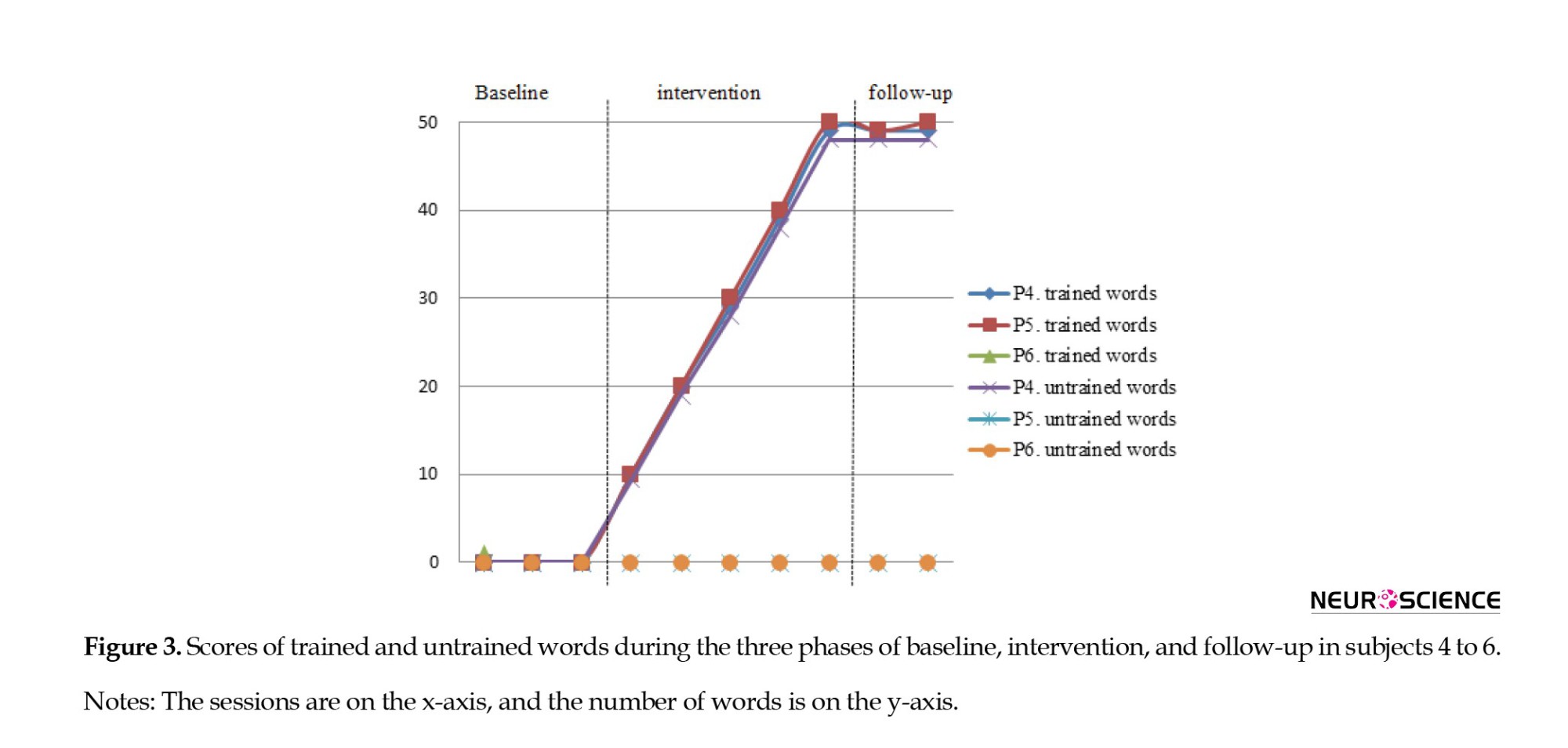

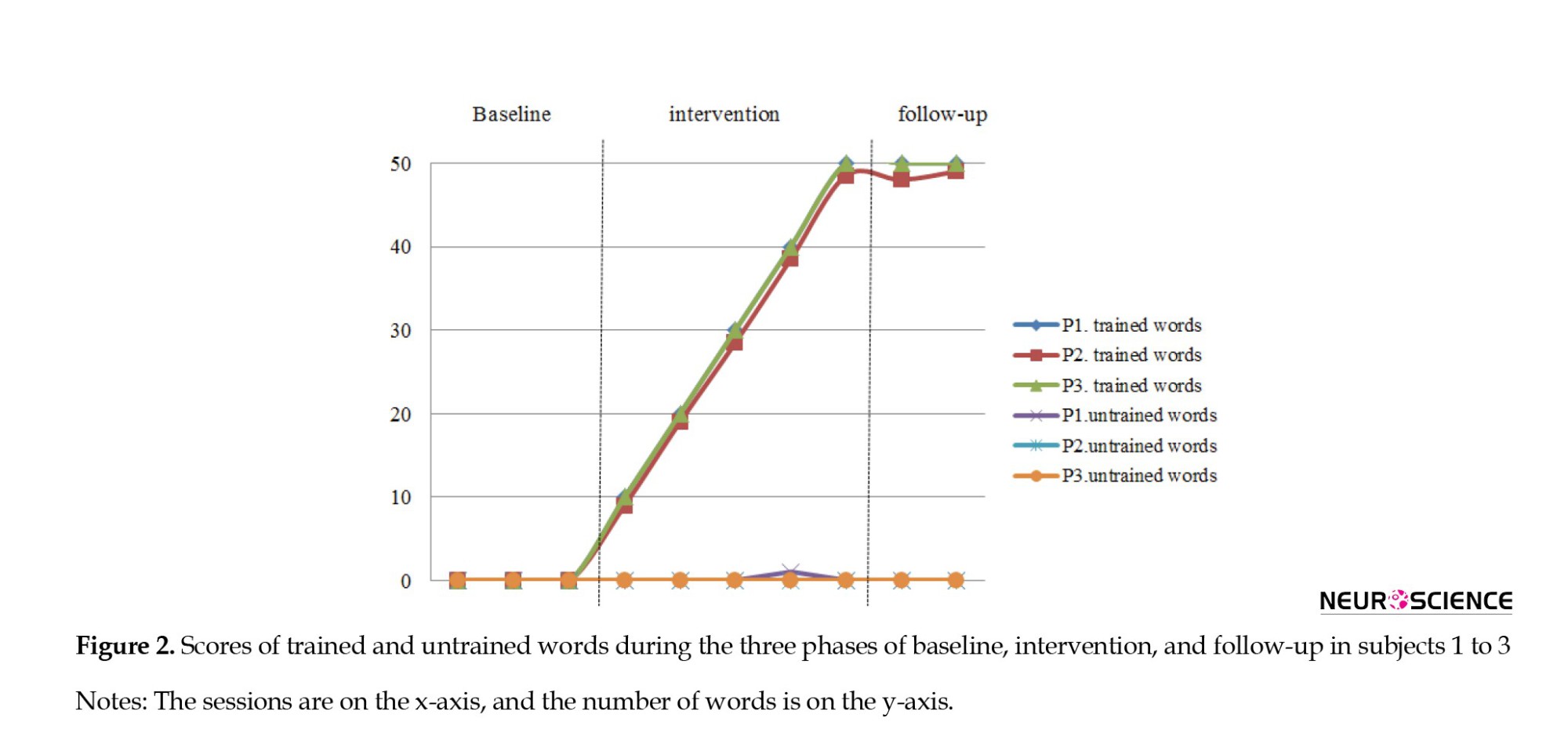

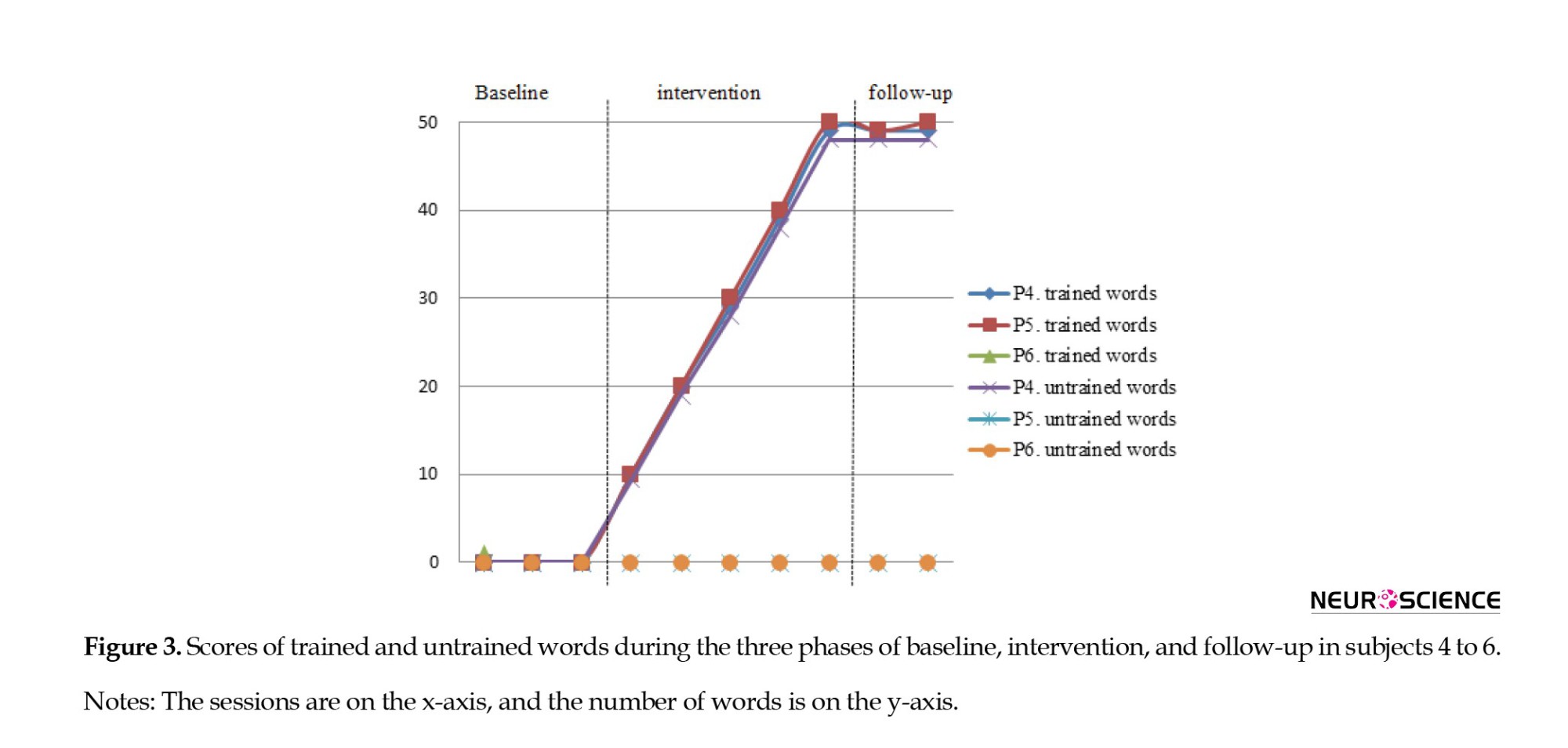

Figures 2 and 3 show visual analysis, which is the basis of single-subject studies and also observing patients’ performance in generalizing treatment to untrained words, the scores at baseline, intervention phases, and its stability in follow-up sessions for each subject in trained and untrained words.

The results showed that patients’ improvement was limited to the trained words treated using developed protocol during the intervention sessions. No generalization was observed to other words (except for subject one, who could write an untrained word without treatment; this may be due to the similarity of this word to one of the trained words). The participants did not significantly improve untrained words compared to the initial baseline assessments.

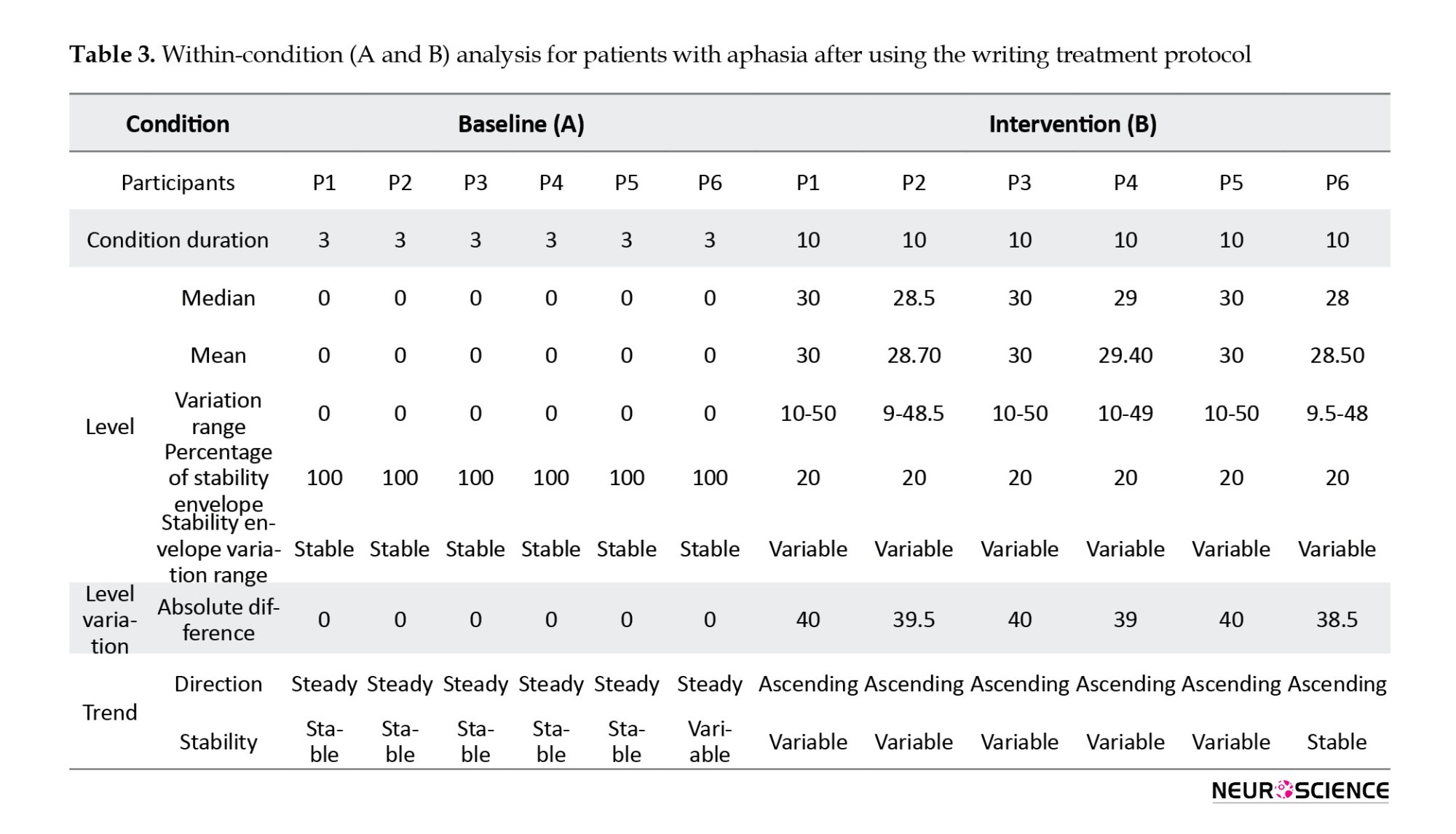

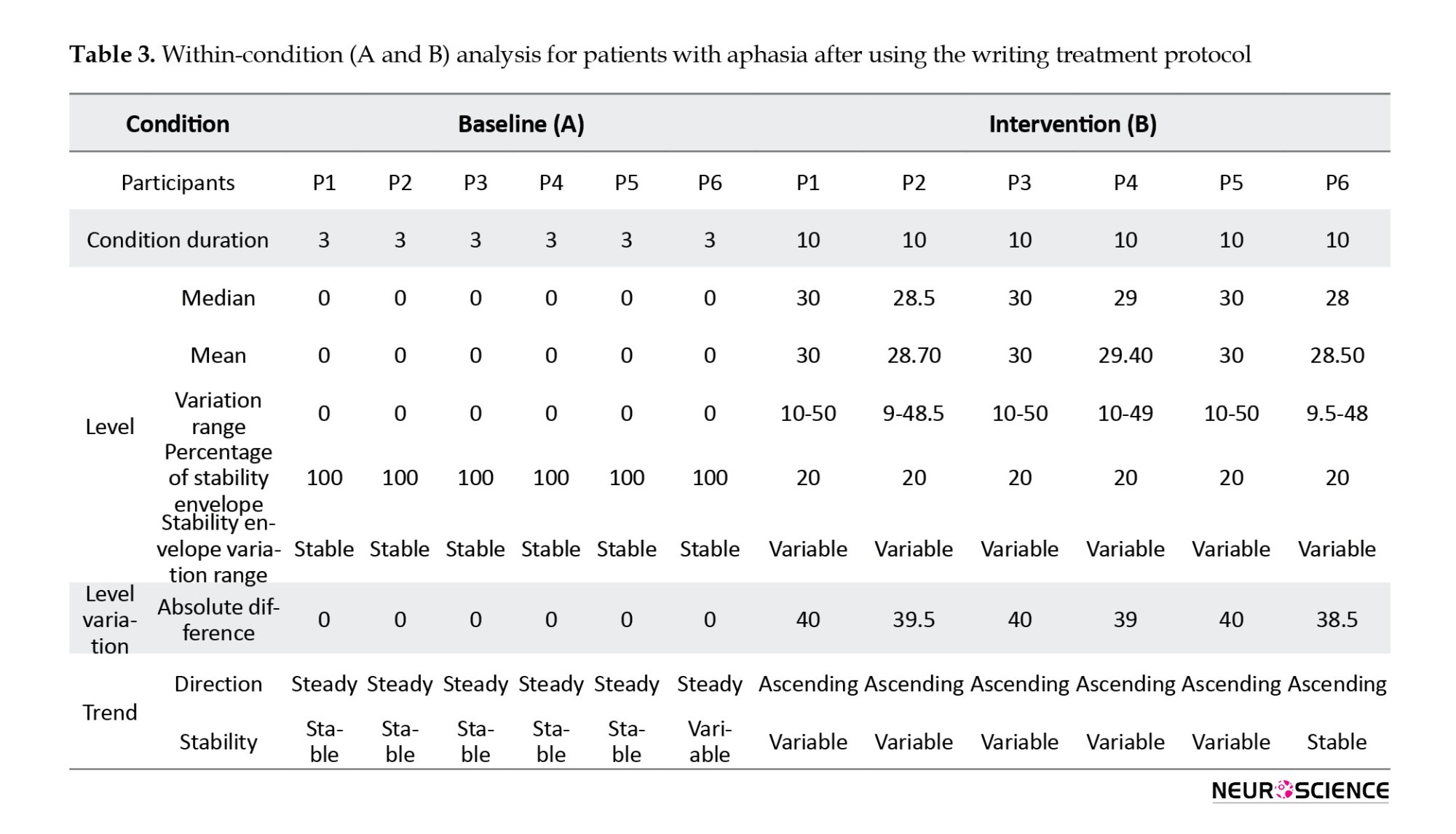

Based on the visual analysis diagrams, the data’s level, trend, and stability in different phases (baseline, intervention, and follow-up) were examined and compared within-condition and between-condition. The within-condition analysis showed that the scores at the baseline in the stability envelope and variation range are stable, and the trend direction is steady and stable. Data are variable in the intervention phase, and the trend direction is ascending, which indicates an improvement in patients’ performance after using the writing treatment.

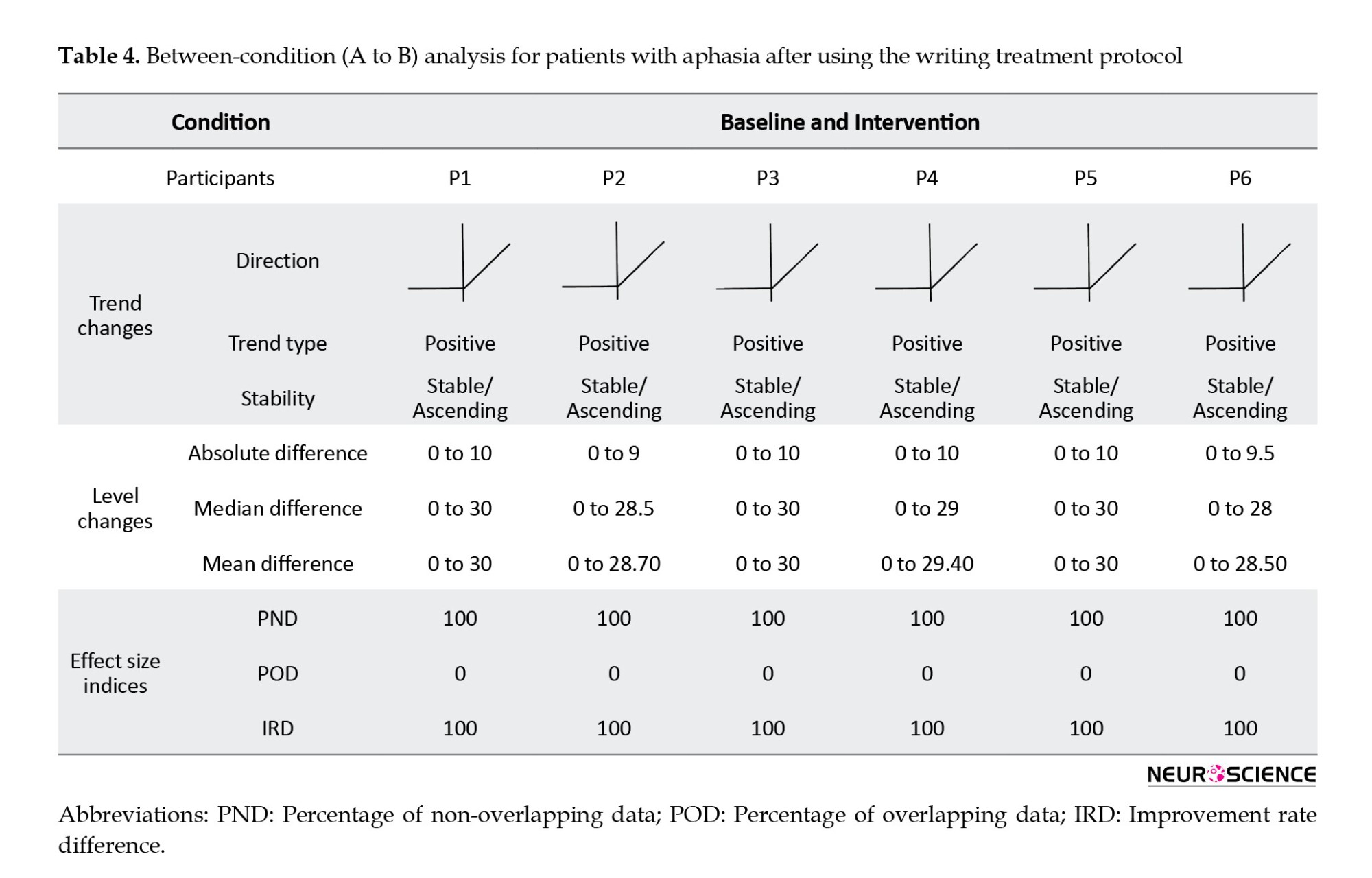

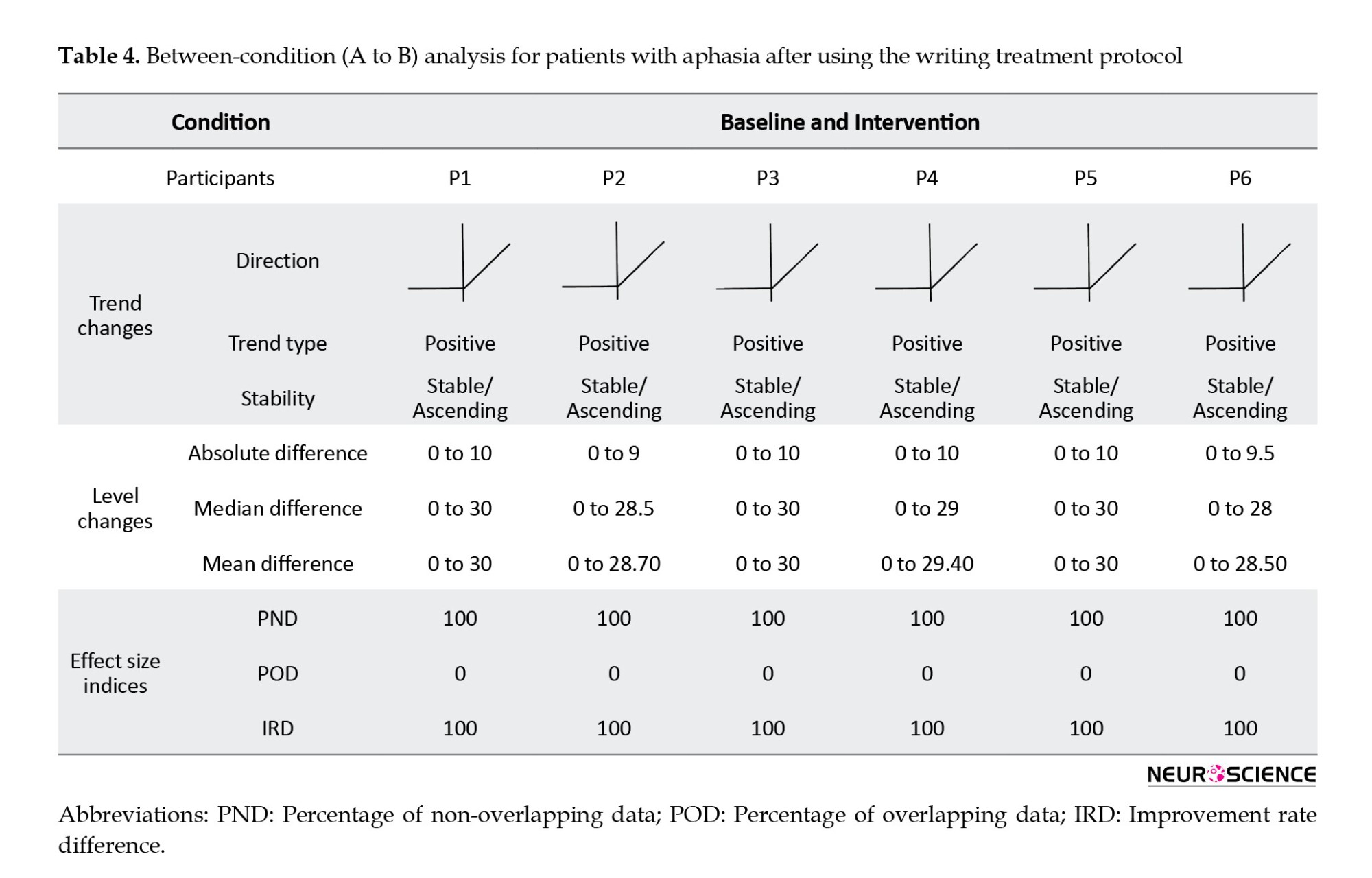

Regarding the between-condition analysis, changes are examined from one condition to the next (baseline to intervention), and in all PWA, the trend was positive and changed from stable to variable. The results of calculating PND, POD, and IRD also showed the acceptable effect of treatment, its effectiveness, and the very high impact of writing therapy on all PWAs. Details of within-condition and between-condition analysis of each subject can be seen in Tables 3 and 4.

The results of comparing the patients’ language performance pre- and post-treatment in Persian aphasia battery showed a statistically significant difference in simple commands (P=0.05), letter and word recognition (P=0.03), word reading (P=0.02), sentence reading (P=0.03), reading comprehension (P=0.02), confrontation naming (P=0.04), and free naming (P=0.05) subtests. Still, there was no significant difference in other subtests of this test.

Since writing treatment was performed in the present study, the writing tasks, including copying, writing letters, words, and sentences of Persian aphasia battery, were analyzed in detail. Furthermore, the results showed that although there were no differences between pre- and post-treatment scores, the PWA could write some words in sentences in the subtest of this post-treatment test. These were the same words that were learned during the treatment. Still, no qualitative improvement in scores was reported because the correct score in this test is given to the patient only when he/she can write whole sentences, so the performance improvement can only be reported quantitatively.

The participants’ performance in speech content and auditory comprehension subtests of P-DAB-1 pre- and post-treatment was not significantly different. Still, the scores of naming (P=0.066) and repetition (P=0.317) subtests indicate a change after the writing treatment, which can be seen in both tasks, although this increase is not significant.

Findings related to Persian aphasia naming test scores also showed that the naming performance of all PWA after treatment using the writing treatment protocol has increased, and in general, these changes are significant (P= 0.027). This outcome indicates that the naming skills in all the PWAs improved after the writing treatment.

4. Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the effects of the writing protocol as an effective augmentative method to improve the communication skills of Persian PWA. It provided writing treatment for these patients for the first time. One of the secondary goals of this research was to develop a protocol appropriate to the written Persian language. The main feature of this treatment protocol was deciding the functional words by PWA and their families. In some traditional aphasia treatments, the therapist is responsible for choosing the target words for the treatment. Still, the main advantage of this protocol was personal words that PWA chose for communication, which led to a higher chance of using these words in daily communication. Previous studies have stated that the patient’s choice of functional words for writing treatment is an important component of intervention because it encourages the patient to use these written words to improve and complement their conversational communication (Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson et al., 2003; Beeson, 1999). For example, Beeson, (1999), in her study as a part of the treatment process, asked the patient to use the trained written words to complete his conversations and determined its success based on the family report. The results showed improvement in using target words in daily interactions (Beeson, 1999). Robson et al., (2001) encouraged patients to apply the words learned in therapy to communicate with another person in the final stages of their study. At this stage, the patients’ families reported using written words to communicate (Robson et al., 2001).

In the present study, the patients’ performance in the follow-up phase and family statements (that report successful written communication using trained words to express needs) showed efficiency in the writing treatment on daily communication. It is suggested that follow-up sessions should be conducted at longer intervals in future studies to investigate the long-term effect. Another critical factor affecting the use of selected functional words in communication and making treatment more successful is the patients’ need for those words. The more the PWA need and use the words in daily interactions, the more likely they are to employ the selected words. In addition, previous studies suggested that it is important to consider variables such as word visualization, frequency, and familiarity in aphasia assessment because all these factors facilitate treatment (Bemani et al., 2021), so in the present study, they were considered well, and their effects were observed on the patient’s improvement. These results are consistent with the study of Robson et al., (2001), stating that using personal and functional words for each patient increases the probability of treatment success.

Another feature of this protocol was the bracketing approach for simplifying incorrect writing attempts and providing anagrams and patterns to help PWA decide the placement of the letters. This ability to arrange, review, and revise the component letters among printed cards without time limitation provides a special condition for PWA that is not available for speech production. Beeson, (1999) stated that the simplification of tasks and the provision of written word letters are essential components for patients with processing deficits and suggested that these patients can use written communication if they cannot speak. Repetitive copies at each step of the writing treatment protocol is another positive feature that stimulates written representations of memory and activates the graphemic buffer so that the PWA can write the target word faster in subsequent attempts. Based on the lexical-semantic approach, this writing treatment protocol could cover short-term and long-term goals due to its unique features. Improving writing performance and writing of trained words with the visual stimulus, and then communication through writing, showed the effectiveness of this writing method. These findings were also reported in the studies of Beeson, (1999), Robson et al., (2001), Beeson et al., (2002), and Clausen et al. (2003).

Another aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of writing treatment using the developed protocol in PWA. The findings showed that although the PWA were different in demographic characteristics and language abilities in an initial assessment, they all significantly improved after the treatment. This improvement was non-random regarding PND, POD, and IRD indices, and the writing treatment had a remarkable effect on trained words. In general, the results reported in this stage are consistent with the studies of Beeson, (1999), Robson et al., (2001), Beeson et al., (2002), Clausen et al. (2003), Ball et al., (2011), and Thiel et al., (2016), all of whom reported performance improvement in PWA after writing treatment. They also stated that lexical-semantic writing treatments are effective regardless of the type, severity, and post-onset time of aphasia (Ball et al., 2011; Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson, 1999; Clausen & Besson, 2003; Robson et al., 2001; Thiel et al., 2016). In addition, Beeson et al., (2003) stated the severity and poor writing skills could not limit treatment outcomes, which were fully similar to the present study’s findings in terms of aphasia severity. Furthermore, the inability to write a single word in the baseline phase did not prevent the improvement and re-learning of writing based on the developed protocol, and all PWA showed significant results after the treatment. Clausen et al. (2003) reported that writing treatment could be beneficial in persistent speech impairments regardless of the time passed since the onset of the lesion. It is similar to the present findings because the post-onset time in PWA varied from 2 to 8 years in this study, but all responded well to the writing treatment protocol.

The results of writing treatment generalization to untrained words showed that none of the patients could write these words after the treatment sessions. It can be stated that PWA could re-learn trained words during treatment, which was specific to these items, and there was no evidence of the improvement of untrained word writing. According to writing cognitive models, the stored memory is created from repetitive copies of target words during protocol steps known as graphemic output lexicon that can be accessed directly from the semantic system. Since there were no repetitive copies of untrained words, no improvement in these words was observed after the treatment. These findings are similar to the results of the study by Beeson, (1999), Robson et al., (2001), and Beeson et al., (2002). They noted that patients’ progress was item-specific and limited to the trained items. The findings do not agree with those obtained from the studies of Thiel et al., (2016), Beeson et al., (2018), Pettit and Tope (2018), and Fein et al. (2020), who mentioned that their writing therapies can be generalized to other untrained words. This difference in the results may be due to the treatment approach used in the mentioned studies. They did not use lexical-semantic writing or this treatment in combination with other methods and thus reported generalization to untrained words. It was revealed that although there was no generalization to untrained words, PWA could write trained words in different situations post-treatment, such as answering questions without using a picture. It can be considered a generalization of treatment in various situations. Sometimes, the target picture during spontaneous communication cannot be provided, so observing this generalization is regarded as a positive capability, which shows that the writing treatment can meet the needs of daily life situations. Another interesting finding observed during and after the treatment sessions was the improved ability to use simple drawings to complement their speech or to draw schematic forms of what they had difficulty expressing and naming to facilitate their communication.

The results showed improvement in some language abilities in initial tests after the writing treatment using the developed protocol, which was mentioned in the findings section. In this regard, few studies have examined the effect of writing treatments on language components in PWA. In addition, naming and word retrieval disorders are common in these patients as significant persistent language deficits that affect spoken and written language (Beeson & Egnor, 2006). According to the cognitive model, the leading cause of the naming disorder may be the impairment of semantics, phonology, and orthography components or the linkage between them as central language processing components. The importance of naming disorder in PWA has encouraged the development of several treatment approaches that improve semantic, phonological, written, and spoken performance. The connections between these lexical processing components provide the basis for different treatments to enhance naming abilities. Therapies used for word retrieval in PWA may use a variety of approaches such as semantic knowledge and lexical-semantic relations (Boyle, 2004; Kiran & Thompson, 2003), phonological processing and speech production (Franklin et al., 2002), or orthographic and written representations. While there are numerous studies on using semantic or phonological competency approaches (Wisenburn & Mahoney, 2009), relatively few studies have examined writing as a tool for speech improvement. There is evidence from previous studies that when a patient with aphasia is unable to use speech for communication, other alternative modalities such as gestures, drawing, or written language may complement or replace speech because written and spoken communication commonly have similar language processes (Black et al., 1989; Rapp et al., 1997). In addition, it has been reported that in some patients, strengthening the central lexical-semantic system can lead to simultaneous improvement of spoken and written naming abilities (Beeson, 1999), which is similar to the findings of the present study, as the results of this study also reported improvement in naming skills after writing treatment using the developed protocol in all the mentioned three tests pre- and post-treatment. This improvement can be considered an advantage of this treatment, which is not limited to the written language and can enhance verbal naming and other language skills. Improving post-treatment naming ability using the writing treatment protocol in the present study is consistent with the study of Beeson & Egnor, (2006). They used a combination of written and verbal naming therapy in their study to investigate the effect of copy and word retrieval therapy with verbal repetition of target words. They compared this combined approach with a treatment that had only verbal repetition. They concluded that combination therapy improved verbal naming performance more than verbal naming therapy alone. In general, they stated that combination therapy uses the residual phonological ability and establishes a link between written function and phonology (Beeson & Egnor, 2006). The results of Beeson et al., (2013) research also showed that the writing treatment approach improved writing and verbal naming abilities.

The present study’s results differ from those of Ball et al., (2011), who used lexical-semantic therapies by adding verbal repetition to writing therapy in patients with severe aphasia. Their findings showed that all the participants improved their writing skills, but none improved their verbal naming performance. The researchers stated that this difference may be due to adding verbal repetition to treatment tasks that are not particularly appropriate for PWA with comorbid disorders, including apraxia (Ball et al., 2011). Further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Regarding the relationship between reading and writing, it was found that all PWA in the present study significantly improved the reading task subtest (i.e. letter and word recognition, word reading, sentence reading, and reading comprehension) after writing treatment using the developed protocol. In this regard, some studies show that the underlying cause of reading and writing disorder in PWA is a defect in phonological processing ability that is not specific to the written language (Crisp & Lambon Ralph, 2006; Rapcsak et al., 2009). Cognitive models also showed that writing and reading are closely related, so the improvement in the reading ability after writing treatment in the present study was not unexpected and is similar to Beeson et al.’s (2010) study. They found that the patients’ reading and writing skills were enhanced through writing treatment by strengthening both lexical and non-lexical paths in these patients.

Finally, it was revealed in the present study that the developed writing treatment protocol significantly improved patients’ communication, so it is suggested that writing therapies can be used in early treatment sessions for stroke patients with aphasia. Also, it is helpful for these patients to communicate as much as possible using various modalities. In this research, writing therapy was based on lexical-semantic approaches to illuminate the efficiency of such methods in communication. Other more comprehensive studies are needed for complete and comprehensive treatment and further improvement of patient function, which employ phonological writing treatments following or alongside lexical-semantic writing approaches.

5. Conclusion

Writing disorder occurs in PWA following a stroke. In this connection, writing treatments are known to improve communication in these patients. It was also found that a developed Persian protocol can improve writing performance and patient communication. The results of the present study were aligned with previous studies that used the lexical-semantic writing therapy method and reported positive results in improving their patients’ communication. Hence, an essential outcome of this study is introducing a writing treatment approach for Persian patients with limited speech, as it can improve their communication ability.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.429).

Funding

The present study was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Seyede Zohre Mousavi, approved by the Department of Speech therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This study was supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Seyede Zohre Mousavi, Nahid Jalilevand, and Hassan Ashayeri; Methodology: Seyede Zohre Mousavi, Nahid Jalilevand, and Jamileh Abolghasemi; Investigation and resources: Seyede Zohre Mousavi; Writing the original draft, and funding acquisition: All authors; Review, and editing: Seyede Zohre Mousavi and Nahid Jalilevand; Supervision: Nahid Jalilevand, Hassan Ashayeri, and Jamileh Abolghasemi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients who participated in this research and their families.

References

Stroke is a focal neurological deficit that results from a localized disorder of cerebral circulation, and it is a significant cause of death and disability in industrialized countries (Wilson & Raghavan, 2018). It is expected that the number of stroke patients increase to 3.4 million between 2012 and 2030 because of lower mortality rate and the rising population age (Ovbiagele et al., 2013). This increase will be more pronounced in future decades (Feigin et al., 2017). Aphasia is one of the most severe post-stroke deficits, affecting one-third of acute stroke patients (Brady et al., 2016; Pollock et al., 2012). It is a general term that describes a range of acquired defects in language function following brain damage, usually affecting the left hemisphere. Aphasia can affect all receptive and expressive communication modalities, i.e. speech, comprehension, reading and writing, and gestures (Berthier & Aging, 2005; Schweizer & Macdonald, 2014).

Since the communication process is affected in people with aphasia (PWA), researchers have always been looking for treatments that can improve their quality of life (QoL). There are two major approaches to therapy. Impairment-based treatments target specific language sub-components; they enhance language functions, such as phonology, lexical semantics, or syntax, in structured therapy to reduce language impairment. The assumption is that doing so will also improve communication skills and, consequently, the QoL. Another approach is functional communication treatments, which target communication skills more directly and do not emphasize generalization in treating speech or language impairments. Also, more than focusing on impairment, functional treatment concentrates on removing environmental barriers to enhance the success of communication (Coppens, 2016).

In some cases, verbal language is severely impaired, and the PWA loses the ability to communicate through speech, so choosing an alternative or complementary approach seems necessary (Beeson et al., 2002). Among the communication ways, writing has almost the closest characteristics to verbal language, and written language can be the best way to communicate, exchange information, and meet needs. Besides being a substitute for speech, writing can also facilitate and improve the patient’s communication quality (Beeson et al., 2000; Beeson et al., 2010; Beeson et al., 2003). In general, written language is an important communication channel that is comparable to verbal language and does not depend on it (Coppens, 2016).

In the aphasia rehabilitation field, writing disorder has received less attention than other language modalities. Most treatments in these patients reported in different studies have focused on verbal language, and there are fewer studies on writing treatment (Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson et al., 2000; Beeson et al., 2010; Beeson et al., 2003). This gap does not underestimate the value of writing treatment in PWA. More recent studies have suggested the significance of writing in improving communication in PWA and reported the appropriate response of these patients to such treatment (Beeson et al., 2018; Clausen & Besson, 2003; Robson et al., 2001; Thiel et al., 2015; Thiel et al., 2016). Most of these studies have been performed as single and multiple case studies and have used writing treatment based on impairment-based writing therapies at the level of single words or sentences using lexical or phonological methods (Beeson et al., 2013; Beeson et al., 2018; Beeson et al., 2010; Thiel & Conroy, 2014). Two lexical-semantic protocols, i.e. anagram and copy treatment and copy and recall treatment designed by Beeson, were widely used in the writing treatment studies of patients with acquired writing disorder, and all of them have reported these treatments successfully in improving patients’ writing skills with an increase in their communication functions (Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson et al., 2000; Beeson et al., 2003; Beeson, 1999). Other studies have used phonological therapies alone or in combination with lexical therapy methods, and most have involved phoneme-to-grapheme conversion. Like lexical therapies, all phonological therapy studies have reported successful results in patients’ writing treatment (Beeson et al., 2018; Beeson et al., 2010; Thiel et al., 2016).

A general review of the literature concludes that writing treatment serves various purposes, including restoring writing skills, stimulating verbal language, or being an alternative to verbal language, especially for patients with limited speech for communication, and all of them are effective (Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson et al., 2000; Beeson et al., 2010; Beeson et al., 2003; Clausen & Besson, 2003; Coppens, 2016; Thiel et al., 2015; Thiel et al., 2016).

Since there is no comprehensive treatment for writing disorders in PWA in Iran, the primary purpose of this study was to design a writing treatment protocol appropriate to the Persian language with the principles of lexical-semantic therapy as a new approach besides the other applied clinical therapies used for PWA and to investigate the effects of writing treatment on improving the communication performance of PWA. The findings of the present study can provide a new perspective on the treatment of stroke patients with Persian-speaking aphasia. This designed treatment protocol can be used in treatment plans in the aphasia field to improve patients’ communication and QoL.

2. Materials and Methods

This study has two main stages. The first stage deals with developing a writing treatment protocol, and the second stage focuses on determining the effect of the developed protocol on PWA. These steps are described below.

The first stage: Developing a writing treatment protocol

This stage included an extensive literature review focusing on writing treatment in PWA, especially the lexical-semantic approach. It was modeled in designing a Persian writing treatment protocol. This approach involves arranging the component letters of the target word and using the bracketing approach for the patient’s failed attempts. In other words, the cues in the treatment step started with simple tasks and gradually became more difficult, and finally, repetitive copies of the correct form of the target word were made.

The steps in the writing treatment protocol were designed considering the characteristics of the Persian written language. Also, the bracketing approach was considered in these steps. The developed protocol included the following steps:

- Providing a picture of the target functional word and asking the PWA to write its name,

- Using semantic, phonological, and verbal repetition cues (in this order) to stimulate word retrieval if the patient cannot write the target word,

- Presenting the printed word syllables on the paper card (typed in size 92 with simple font) irregularly so that the PWA can retrieve the target word by arranging them,

- Arranging the printed letters of the word that are presented irregularly to the PWA,

- Presenting a few additional letters that included vowels and consonants on the cards, as well as different forms of letters related to a phoneme that were visually similar to the component letters of the target word, so that the PWA can select the correct letters from them and write the target word,

- In the last step, hiding all the writing patterns so that the patient retrieves the written word from memory and finally writes it independently.

In all the above steps, if the patient cannot write the target functional word, the therapist arranges the cards correctly to instruct the PWA to use them as a template. After the patient can write the word correctly, they should copy the correct pattern three times.

In this way, an initial version of the writing treatment protocol was developed with the short-term plan of writing the functional word correctly considered a list for training during treatment sessions using the writing treatment protocol. Also, the long-term goal was to communicate and request needs through writing.

To determine the validity of the developed protocol, its final version was made available to 10 experts in the field, including speech and language pathologists and linguists, to apply their comments by considering the study’s purpose and the target population. They were asked to comment on the appropriateness of the protocol and correctly prioritize the cueing hierarchy of the treatment protocol. Then, their answers and suggestions were analyzed and applied to the treatment protocol. The statistical methods used in this section included content validity index (CVI) and content validity ratio (CVR).

The second stage: Evaluating the effectiveness of writing treatment in PWA using the developed protocol

The research in this section was a single-subject study with an ABA design. In such research, few subjects are studied at any time, and the changes resulting from the treatment program are evaluated in relation to the same subject, not in relation to other participants; that is, the participant plays both the role of the subject and the control. Regarding the nature of the single-subject study and the length of the evaluation and treatment process, 6 PWA were studied in this project, according to the inclusion criteria: Unilateral damage of the left hemisphere based on the brain imaging and neurologist diagnosis, deficit due to stroke, no previous history of stroke, no history of cognitive disorder based on mini-mental state examination (MMSE), no other neurological disorder such as Parkinson and Alzheimer, chronic stage, i.e. at least 6 months post-onset time, monolingualism, right-handedness, and no concomitant therapeutic intervention during the writing treatment.

First, according to the neurologist’s diagnosis and brain imaging report, the location of the lesion was determined, and brain damage in the left hemisphere due to stroke was confirmed. All of the subjects’ aphasia was classified as non-fluent. Lesions in the left perisylvian regions had caused it. Then, the intervention process was explained to PWA and their families for completing informed consent. Ethical issues were considered, including the following: All PWA participated voluntarily and were free to leave the study whenever they wanted; their information remained confidential, and the Committee of Iran University Medical Sciences approved the study.

A demographic questionnaire was completed for each PWA, including personal information and a medical history report. All PWA were evaluated through initial pre-treatment tests including Persian aphasia battery for assessing severity of aphasia in different aspects of language and also for differential diagnosis, the bedside version of Persian diagnostic aphasia battery (P-DAB-1) (Nilipour et al., 2014) for determining aphasia severity based on aphasia quotient (AQ), and the aphasia naming test (Nilipour, 2011) for clinical assessment of naming skills. The inclusion criteria included patients with aphasia who were in the chronic phase, had brain damage in the left hemisphere, were non-fluent, had limited speech for communication, were not receiving other speech therapy, and were willing to learn writing therapy.

Then, an ABA design was performed on each patient. First, the functional words of any participant were selected by consulting with the PWA and their families. These were the personal words that the PWA frequently used in daily life and were divided into 50 trained words into 10 sets of 5 words (which were treated 1 set during each treatment session based on a writing treatment protocol) and 50 untrained words (to evaluate the generalization of treatment to other words that were not treated). They were used at baseline and probes during treatment sessions to assess the maintenance and stability of scores after treatment in the follow-up phase.

The baseline phase was repeated for 3 consecutive weeks (1 session per week), and their results were plotted as a graph called the baseline diagram. After the baseline phase and stable writing performance of PWA, the intervention phase started using the developed writing treatment protocol. Furthermore, according to previous studies, the number of sessions and treatment intervention duration were the same for all subjects, and 10 sessions were performed twice a week for 1 hour (Beeson, 1999). At this phase, probes were carried out regularly at the end of each week, and both trained and untrained words were evaluated to determine the resulting changes and improvements. These results were drawn as a second graph beside the first diagram. In the third phase, 1 month after intervention sessions, all evaluations were carried out again (two sessions per week). The results were recorded in the diagram. This phase showed the generalization, stabilization, or possible changes in treatment. Ultimately, the Persian aphasia battery, P-DAB-1, and aphasia naming test were re-administered. These stages are shown in detail in Figure 1.

Statistical analysis

In this single-subject study, baseline, intervention, and follow-up diagrams were drawn for all the subjects. Visual analysis (stability and changes in within-condition and between-condition) and effect size indices like improvement rate difference (IRD), percentage of non-overlapping data (PND), and percentage of overlapping data (POD) were examined. In analyzing the results of the Persian aphasia battery, the aphasia naming test and P-DAB-1 test before and after treatment based on the developed writing treatment protocol, non-parametric Wilcoxon was used. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 22 at a 95% confidence level.

3. Results

The first stage of the study

An expert panel determined the content validity of the developed writing treatment protocol. Ten experts were provided with comments on each step of this protocol in three categories: Necessary, useful but not necessary, and not necessary. Then, CVR was determined. As in the Lawshe table, the CVR for all steps was greater than 0.62. This figure indicates that essential steps have been taken in this treatment protocol. To calculate CVI, the experts were asked to score the three criteria of relevance, simplicity, and clarity of the developed protocol steps based on a 4-point Likert scale (not relevant, somewhat relevant, quite relevant, and very relevant, in which 0 reflected no relevance between the mentioned items, and 4 indicated the most relevance). The CVI showed that the experts chose relevant and very relevant options for all the designed steps, and the CVI score was higher than 0.90, so it was appropriate.

The second stage of the study

Six patients with aphasia following a stroke in the left hemisphere were studied, all of whom were right-handed before the stroke, but they used the left hand to write in this study because of right hemiplegia or paresis after the lesion. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Several patients may participate in single-subject studies, but the data are analyzed separately for each participant, and the subject performance changes are scored in different phases during each session. The present study shows the effect of intervention in 50 trained words using the writing treatment protocol in the baseline phase, weekly probes, and follow-up in PWA in Table 2.

The pre-treatment results showed that before treatment, no person with aphasia could write even one of the selected functional words, which was shown in the baseline sessions (3 times) with zero scores. Initial evaluations before the starting treatment showed that among the 6 PWA, only two patients (1 and 3) were interested in re-learning writing performance. However, the other four patients did not try because of frustration and stated that they could not write words. However, interesting results were obtained for all PWA after starting the writing therapy session using the developed protocol. Higher scores per session showed improvement during the intervention. A noteworthy point is that the scores at the follow-up phase showed that this progress was consistent and did not decrease over time.

Figures 2 and 3 show visual analysis, which is the basis of single-subject studies and also observing patients’ performance in generalizing treatment to untrained words, the scores at baseline, intervention phases, and its stability in follow-up sessions for each subject in trained and untrained words.

The results showed that patients’ improvement was limited to the trained words treated using developed protocol during the intervention sessions. No generalization was observed to other words (except for subject one, who could write an untrained word without treatment; this may be due to the similarity of this word to one of the trained words). The participants did not significantly improve untrained words compared to the initial baseline assessments.

Based on the visual analysis diagrams, the data’s level, trend, and stability in different phases (baseline, intervention, and follow-up) were examined and compared within-condition and between-condition. The within-condition analysis showed that the scores at the baseline in the stability envelope and variation range are stable, and the trend direction is steady and stable. Data are variable in the intervention phase, and the trend direction is ascending, which indicates an improvement in patients’ performance after using the writing treatment.

Regarding the between-condition analysis, changes are examined from one condition to the next (baseline to intervention), and in all PWA, the trend was positive and changed from stable to variable. The results of calculating PND, POD, and IRD also showed the acceptable effect of treatment, its effectiveness, and the very high impact of writing therapy on all PWAs. Details of within-condition and between-condition analysis of each subject can be seen in Tables 3 and 4.

The results of comparing the patients’ language performance pre- and post-treatment in Persian aphasia battery showed a statistically significant difference in simple commands (P=0.05), letter and word recognition (P=0.03), word reading (P=0.02), sentence reading (P=0.03), reading comprehension (P=0.02), confrontation naming (P=0.04), and free naming (P=0.05) subtests. Still, there was no significant difference in other subtests of this test.

Since writing treatment was performed in the present study, the writing tasks, including copying, writing letters, words, and sentences of Persian aphasia battery, were analyzed in detail. Furthermore, the results showed that although there were no differences between pre- and post-treatment scores, the PWA could write some words in sentences in the subtest of this post-treatment test. These were the same words that were learned during the treatment. Still, no qualitative improvement in scores was reported because the correct score in this test is given to the patient only when he/she can write whole sentences, so the performance improvement can only be reported quantitatively.

The participants’ performance in speech content and auditory comprehension subtests of P-DAB-1 pre- and post-treatment was not significantly different. Still, the scores of naming (P=0.066) and repetition (P=0.317) subtests indicate a change after the writing treatment, which can be seen in both tasks, although this increase is not significant.

Findings related to Persian aphasia naming test scores also showed that the naming performance of all PWA after treatment using the writing treatment protocol has increased, and in general, these changes are significant (P= 0.027). This outcome indicates that the naming skills in all the PWAs improved after the writing treatment.

4. Discussion

The present study was conducted to investigate the effects of the writing protocol as an effective augmentative method to improve the communication skills of Persian PWA. It provided writing treatment for these patients for the first time. One of the secondary goals of this research was to develop a protocol appropriate to the written Persian language. The main feature of this treatment protocol was deciding the functional words by PWA and their families. In some traditional aphasia treatments, the therapist is responsible for choosing the target words for the treatment. Still, the main advantage of this protocol was personal words that PWA chose for communication, which led to a higher chance of using these words in daily communication. Previous studies have stated that the patient’s choice of functional words for writing treatment is an important component of intervention because it encourages the patient to use these written words to improve and complement their conversational communication (Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson et al., 2003; Beeson, 1999). For example, Beeson, (1999), in her study as a part of the treatment process, asked the patient to use the trained written words to complete his conversations and determined its success based on the family report. The results showed improvement in using target words in daily interactions (Beeson, 1999). Robson et al., (2001) encouraged patients to apply the words learned in therapy to communicate with another person in the final stages of their study. At this stage, the patients’ families reported using written words to communicate (Robson et al., 2001).

In the present study, the patients’ performance in the follow-up phase and family statements (that report successful written communication using trained words to express needs) showed efficiency in the writing treatment on daily communication. It is suggested that follow-up sessions should be conducted at longer intervals in future studies to investigate the long-term effect. Another critical factor affecting the use of selected functional words in communication and making treatment more successful is the patients’ need for those words. The more the PWA need and use the words in daily interactions, the more likely they are to employ the selected words. In addition, previous studies suggested that it is important to consider variables such as word visualization, frequency, and familiarity in aphasia assessment because all these factors facilitate treatment (Bemani et al., 2021), so in the present study, they were considered well, and their effects were observed on the patient’s improvement. These results are consistent with the study of Robson et al., (2001), stating that using personal and functional words for each patient increases the probability of treatment success.

Another feature of this protocol was the bracketing approach for simplifying incorrect writing attempts and providing anagrams and patterns to help PWA decide the placement of the letters. This ability to arrange, review, and revise the component letters among printed cards without time limitation provides a special condition for PWA that is not available for speech production. Beeson, (1999) stated that the simplification of tasks and the provision of written word letters are essential components for patients with processing deficits and suggested that these patients can use written communication if they cannot speak. Repetitive copies at each step of the writing treatment protocol is another positive feature that stimulates written representations of memory and activates the graphemic buffer so that the PWA can write the target word faster in subsequent attempts. Based on the lexical-semantic approach, this writing treatment protocol could cover short-term and long-term goals due to its unique features. Improving writing performance and writing of trained words with the visual stimulus, and then communication through writing, showed the effectiveness of this writing method. These findings were also reported in the studies of Beeson, (1999), Robson et al., (2001), Beeson et al., (2002), and Clausen et al. (2003).

Another aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of writing treatment using the developed protocol in PWA. The findings showed that although the PWA were different in demographic characteristics and language abilities in an initial assessment, they all significantly improved after the treatment. This improvement was non-random regarding PND, POD, and IRD indices, and the writing treatment had a remarkable effect on trained words. In general, the results reported in this stage are consistent with the studies of Beeson, (1999), Robson et al., (2001), Beeson et al., (2002), Clausen et al. (2003), Ball et al., (2011), and Thiel et al., (2016), all of whom reported performance improvement in PWA after writing treatment. They also stated that lexical-semantic writing treatments are effective regardless of the type, severity, and post-onset time of aphasia (Ball et al., 2011; Beeson et al., 2002; Beeson, 1999; Clausen & Besson, 2003; Robson et al., 2001; Thiel et al., 2016). In addition, Beeson et al., (2003) stated the severity and poor writing skills could not limit treatment outcomes, which were fully similar to the present study’s findings in terms of aphasia severity. Furthermore, the inability to write a single word in the baseline phase did not prevent the improvement and re-learning of writing based on the developed protocol, and all PWA showed significant results after the treatment. Clausen et al. (2003) reported that writing treatment could be beneficial in persistent speech impairments regardless of the time passed since the onset of the lesion. It is similar to the present findings because the post-onset time in PWA varied from 2 to 8 years in this study, but all responded well to the writing treatment protocol.

The results of writing treatment generalization to untrained words showed that none of the patients could write these words after the treatment sessions. It can be stated that PWA could re-learn trained words during treatment, which was specific to these items, and there was no evidence of the improvement of untrained word writing. According to writing cognitive models, the stored memory is created from repetitive copies of target words during protocol steps known as graphemic output lexicon that can be accessed directly from the semantic system. Since there were no repetitive copies of untrained words, no improvement in these words was observed after the treatment. These findings are similar to the results of the study by Beeson, (1999), Robson et al., (2001), and Beeson et al., (2002). They noted that patients’ progress was item-specific and limited to the trained items. The findings do not agree with those obtained from the studies of Thiel et al., (2016), Beeson et al., (2018), Pettit and Tope (2018), and Fein et al. (2020), who mentioned that their writing therapies can be generalized to other untrained words. This difference in the results may be due to the treatment approach used in the mentioned studies. They did not use lexical-semantic writing or this treatment in combination with other methods and thus reported generalization to untrained words. It was revealed that although there was no generalization to untrained words, PWA could write trained words in different situations post-treatment, such as answering questions without using a picture. It can be considered a generalization of treatment in various situations. Sometimes, the target picture during spontaneous communication cannot be provided, so observing this generalization is regarded as a positive capability, which shows that the writing treatment can meet the needs of daily life situations. Another interesting finding observed during and after the treatment sessions was the improved ability to use simple drawings to complement their speech or to draw schematic forms of what they had difficulty expressing and naming to facilitate their communication.

The results showed improvement in some language abilities in initial tests after the writing treatment using the developed protocol, which was mentioned in the findings section. In this regard, few studies have examined the effect of writing treatments on language components in PWA. In addition, naming and word retrieval disorders are common in these patients as significant persistent language deficits that affect spoken and written language (Beeson & Egnor, 2006). According to the cognitive model, the leading cause of the naming disorder may be the impairment of semantics, phonology, and orthography components or the linkage between them as central language processing components. The importance of naming disorder in PWA has encouraged the development of several treatment approaches that improve semantic, phonological, written, and spoken performance. The connections between these lexical processing components provide the basis for different treatments to enhance naming abilities. Therapies used for word retrieval in PWA may use a variety of approaches such as semantic knowledge and lexical-semantic relations (Boyle, 2004; Kiran & Thompson, 2003), phonological processing and speech production (Franklin et al., 2002), or orthographic and written representations. While there are numerous studies on using semantic or phonological competency approaches (Wisenburn & Mahoney, 2009), relatively few studies have examined writing as a tool for speech improvement. There is evidence from previous studies that when a patient with aphasia is unable to use speech for communication, other alternative modalities such as gestures, drawing, or written language may complement or replace speech because written and spoken communication commonly have similar language processes (Black et al., 1989; Rapp et al., 1997). In addition, it has been reported that in some patients, strengthening the central lexical-semantic system can lead to simultaneous improvement of spoken and written naming abilities (Beeson, 1999), which is similar to the findings of the present study, as the results of this study also reported improvement in naming skills after writing treatment using the developed protocol in all the mentioned three tests pre- and post-treatment. This improvement can be considered an advantage of this treatment, which is not limited to the written language and can enhance verbal naming and other language skills. Improving post-treatment naming ability using the writing treatment protocol in the present study is consistent with the study of Beeson & Egnor, (2006). They used a combination of written and verbal naming therapy in their study to investigate the effect of copy and word retrieval therapy with verbal repetition of target words. They compared this combined approach with a treatment that had only verbal repetition. They concluded that combination therapy improved verbal naming performance more than verbal naming therapy alone. In general, they stated that combination therapy uses the residual phonological ability and establishes a link between written function and phonology (Beeson & Egnor, 2006). The results of Beeson et al., (2013) research also showed that the writing treatment approach improved writing and verbal naming abilities.

The present study’s results differ from those of Ball et al., (2011), who used lexical-semantic therapies by adding verbal repetition to writing therapy in patients with severe aphasia. Their findings showed that all the participants improved their writing skills, but none improved their verbal naming performance. The researchers stated that this difference may be due to adding verbal repetition to treatment tasks that are not particularly appropriate for PWA with comorbid disorders, including apraxia (Ball et al., 2011). Further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Regarding the relationship between reading and writing, it was found that all PWA in the present study significantly improved the reading task subtest (i.e. letter and word recognition, word reading, sentence reading, and reading comprehension) after writing treatment using the developed protocol. In this regard, some studies show that the underlying cause of reading and writing disorder in PWA is a defect in phonological processing ability that is not specific to the written language (Crisp & Lambon Ralph, 2006; Rapcsak et al., 2009). Cognitive models also showed that writing and reading are closely related, so the improvement in the reading ability after writing treatment in the present study was not unexpected and is similar to Beeson et al.’s (2010) study. They found that the patients’ reading and writing skills were enhanced through writing treatment by strengthening both lexical and non-lexical paths in these patients.

Finally, it was revealed in the present study that the developed writing treatment protocol significantly improved patients’ communication, so it is suggested that writing therapies can be used in early treatment sessions for stroke patients with aphasia. Also, it is helpful for these patients to communicate as much as possible using various modalities. In this research, writing therapy was based on lexical-semantic approaches to illuminate the efficiency of such methods in communication. Other more comprehensive studies are needed for complete and comprehensive treatment and further improvement of patient function, which employ phonological writing treatments following or alongside lexical-semantic writing approaches.

5. Conclusion

Writing disorder occurs in PWA following a stroke. In this connection, writing treatments are known to improve communication in these patients. It was also found that a developed Persian protocol can improve writing performance and patient communication. The results of the present study were aligned with previous studies that used the lexical-semantic writing therapy method and reported positive results in improving their patients’ communication. Hence, an essential outcome of this study is introducing a writing treatment approach for Persian patients with limited speech, as it can improve their communication ability.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.429).

Funding

The present study was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Seyede Zohre Mousavi, approved by the Department of Speech therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This study was supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Seyede Zohre Mousavi, Nahid Jalilevand, and Hassan Ashayeri; Methodology: Seyede Zohre Mousavi, Nahid Jalilevand, and Jamileh Abolghasemi; Investigation and resources: Seyede Zohre Mousavi; Writing the original draft, and funding acquisition: All authors; Review, and editing: Seyede Zohre Mousavi and Nahid Jalilevand; Supervision: Nahid Jalilevand, Hassan Ashayeri, and Jamileh Abolghasemi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients who participated in this research and their families.

References

Ball, A. L., de Riesthal, M., Breeding, V. E., & Mendoza, D. E. J. A. (2011). Modified ACT and CART in severe aphasia. Aphasiology, 25(6-7), 836-848. [DOI:10.1080/02687038.2010.544320]

Beeson, P. M., & Egnor, H. (2006). Combining treatment for written and spoken naming. Journal of The International Neuropsychological Society: JINS, 12(6), 816–827. [DOI:10.1017/S1355617706061005] [PMID]

Beeson, P. M., Higginson, K., & Rising, K. (2013). Writing treatment for aphasia: A texting approach. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 56(3), 945–955. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0360)] [PMID]

Beeson, P. M., Hirsch, F. M., & Rewega, M. A. (2002). Successful single-word writing treatment: Experimental analyses of four cases. Aphasiology, 16(4-6), 473-491. [DOI:10.1080/02687030244000167]

Beeson, P. M., Rewega, M. A., Vail, S., & Rapcsak, S. Z. (2000). Problem-solving approach to agraphia treatment: Interactive use of lexical and sublexical spelling routes. Aphasiology, 14(5-6), 551-565. [DOI:10.1080/026870300401315]

Beeson, P. M., Rising, K., DeMarco, A. T., Foley, T. H., & Rapcsak, S. Z. (2018). The nature and treatment of phonological text agraphia. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 28(4), 568–588. [DOI:10.1080/09602011.2016.1199387] [PMID]

Beeson, P. M., Rising, K., Kim, E. S., & Rapcsak, S. Z. (2010). A treatment sequence for phonological alexia/agraphia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 53(2), 450–468. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0229)] [PMID]

Beeson, P. M., Rising, K., & Volk, J. (2003). Writing treatment for severe aphasia: who benefits? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 46(5), 1038–1060. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2003/083)] [PMID]

Beeson, P. M. (1999). Treating acquired writing impairment: Strengthening graphemic representations. Aphasiology, 13(9-11), 767-785. [DOI:10.1080/026870399401867]

Bemani, Z., Moayedfar, S., & Ghasisin, L. J. A. (2022). Psycholinguistic variables influencing word retrieval in Persian speaking people with aphasia. Aphasiology, 36(7), 868-882. [DOI:10.1080/02687038.2021.1907292]

Berthier, M. L. (2005). Poststroke aphasia: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. Drugs & Aging, 22(2), 163–182.[DOI:10.2165/00002512-200522020-00006] [PMID]

Black, S. E., Behrmann, M., Bass, K., & Hacker, P. (1989). Selective writing impairment: Beyond the allographic code. Aphasiology, 3(3), 265-277. [DOI:10.1080/02687038908248994]

Boyle, M. (2004). Semantic feature analysis treatment for anomia in two fluent aphasia syndromes. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 13(3), 236–249. [DOI:10.1044/1058-0360(2004/025)] [PMID]

Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2016(6), CD000425. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4] [PMID]

Clausen, N., & Besson, P. (2003). Conversational use of writing in severe aphasia: A group treatment approach. Aphasiology, 17(6-7), 625-644. [DOI:10.1080/02687030344000003]

Coppens, P. (2016). Aphasia and related neurogenic communication disorders. Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Publishers. [Link]

Crisp, J., & Lambon Ralph, M. A. (2006). Unlocking the nature of the phonological-deep dyslexia continuum: The keys to reading aloud are in phonology and semantics. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 18(3), 348-362. [DOI:10.1162/jocn.2006.18.3.348]

Feigin, V. L., Norrving, B., & Mensah, G. A. (2017). Global burden of stroke. Circulation Research, 120(3), 439–448. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308413] [PMID]

Fein, M., Bayley, C., Rising, K., & Beeson, P. M. (2020). A structured approach to train text messaging in an individual with aphasia. Aphasiology, 34(1), 102-118. [DOI:10.1080/02687038.2018.1562150]

Franklin, S., Buerk, F., & Howard, D. J. A. (2002). Generalised improvement in speech production for a subject with reproduction conduction aphasia. Aphasiology, 16(10-11), 1087-1114. [DOI:10.1080/02687030244000491]

Kiran, S., & Thompson, C. K. (2003). The role of semantic complexity in treatment of naming deficits: Training semantic categories in fluent aphasia by controlling exemplar typicality. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 46(4), 773–787. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2003/061)] [PMID]

Nilipour, R., Pourshahbaz, A., & Ghoreyshi, Z. S. (2014). Reliability and validity of bedside version of Persian WAB (P-WAB-1). Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 5(4), 253-258. [PMID]

Nilipour, R. (2011). [Aphasia naming test (Persian)]. Tehran: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. [Link]

Ovbiagele, B., Goldstein, L. B., Higashida, R. T., Howard, V. J., Johnston, S. C., & Khavjou, O. A., et al. (2013). Forecasting the future of stroke in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Stroke, 44(8), 2361–2375. [DOI:10.1161/STR.0b013e31829734f2] [PMID]

Pettit, E., & Tope, L. (2018). Retraining spelling and writing for conversation: A group intervention approach for people with aphasia and dysgraphia. Aphasiology, 32(sup1), 162-164. [DOI:10.1080/02687038.2018.1487012]

Pollock, A., St George, B., Fenton, M., & Firkins, L. (2012). Top ten research priorities relating to life after stroke. The Lancet. Neurology, 11(3), 209. [DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70029-7] [PMID]

Rapcsak, S. Z., Beeson, P. M., Henry, M. L., Leyden, A., Kim, E., & Rising, K., et al. (2009). Phonological dyslexia and dysgraphia: Cognitive mechanisms and neural substrates. Cortex; A Journal Devoted to The Study of The Nervous System and Behavior, 45(5), 575–591. [DOI:10.1016/j.cortex.2008.04.006] [PMID]

Rapp, B., & Caramazza, A. (1997). The modality-specific organization of grammatical categories: Evidence from impaired spoken and written sentence production. Brain and Language, 56(2), 248–286. [DOI:10.1006/brln.1997.1735] [PMID]

Robson, J., Marshall, J., Chiat, S., & Pring, T. (2001). Enhancing communication in jargon aphasia: A small group study of writing therapy. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 36(4), 471–488. [DOI:10.1080/13682820110089371] [PMID]

Schweizer, T. A., & Macdonald, R. L. (2014). The behavioral consequences of stroke. Berlin: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4614-7672-6]

Thiel, L., & Conroy, P. (2014). A comparison of errorless and errorful therapies for dysgraphia after stroke. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24(2), 172–201. [DOI:10.1080/09602011.2013.875925] [PMID]

Thiel, L., Sage, K., & Conroy, P. (2015). Retraining writing for functional purposes: A review of the writing therapy literature. Aphasiology, 29(4), 423-441. [DOI:10.1080/02687038.2014.965059]

Thiel, L., Sage, K., & Conroy, P. (2016). Comparing uni-modal and multi-modal therapies for improving writing in acquired dysgraphia after stroke. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 26(3), 345–373. [DOI:10.1080/09602011.2015.1026357] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Cognitive Neuroscience

Received: 2022/04/27 | Accepted: 2023/03/5 | Published: 2025/03/18

Received: 2022/04/27 | Accepted: 2023/03/5 | Published: 2025/03/18

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|