Volume 14, Issue 1 (January & February 2023)

BCN 2023, 14(1): 19-30 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Noorazar S G, Emamizad S, Fakhari-Dehkharghani A, Pouya P. The Therapeutic Effect of Electroconvulsive Therapy in Patients With Obsessive-compulsive Disorder: A Quasi-experimental Study. BCN 2023; 14 (1) :19-30

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2208-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2208-en.html

1- Research Center of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

2- Aging Research Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

2- Aging Research Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Keywords: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, Electroconvulsive therapy, Yale-Brown criteria, Treatment-resistant OCD

Full-Text [PDF 762 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

1. Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is an incapacitating and long-standing neuropsychiatric disorder prevalent in roughly 2% of the population (Fullana et al., 2010). Furthermore, remarkable growth in OCD prevalence has been reported during the COVID-19 pandemic (Abba-Aji et al., 2020). Contamination (washing), checking, symmetry (ordering/arranging), ruminations (intrusive thoughts), sexual/religious, and hoarding are the most common aspects of OCD symptoms (Rosario-Campos et al., 2006), which can cause social and occupational problems (Mancebo et al., 2008) and ultimately high suicidal thoughts and attempts in severe cases (Albert, et al., 2019).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and clomipramine are mainly used to treat OCD (Marazziti & Consoli, 2010). These medications prevent the reabsorption or secretion of serotonin in the synaptic space and increase the concentration of serotonin in the synapses. It is demonstrated that increasing serotonin levels in the frontal lobe alleviate OCD symptoms. Moreover, olanzapine and risperidone are antipsychotic medications prescribed for treating OCD symptoms to enhance SSRI effects. Studies show that these medications have partially or completely suboptimal efficacy in OCD patients, mainly in severe cases (in 40% to 60% of patients). Treatment-resistant OCD subjects are patients who receive an adequate trial of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (clomipramine or SSRI) and do not respond or show unsatisfactory response to treatment; this condition accounts for 40%-50% of all OCD patients. The definition of treatment-refractory OCD may imply a greater degree of resistance to interventions, including non-respond to SSRIs/clomipramine, augmentation strategies, and behavioral intervention (Fontenelle, Nascimento, Mendlowicz, Shavitt, & Versiani, 2007; Simpson et al., 2013). Therefore, developing novel evidence-based strategies for managing treatment-resistant OCD patients is necessary (Simpson, 2009). Evolving therapies for severe and treatment-resistant OCD comprise psychotherapies, novel pharmacotherapies, immunological therapies, pharmacogenetics, non-invasive neurostimulation, and invasive neurostimulation (Fineberg et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the evidence is limited for most of these novel therapeutic strategies (Carrillo, 2012). Despite the considerable improvement of patients using invasive neurostimulation therapies such as deep brain stimulation (de Koning et al. , 2011), limbic system surgery (Sheth et al., 2013), and ablative neurosurgery, they cannot be considered the first choice of treatment due to the need for general anesthesia and high costs (Denys, 2006; Fineberg & Gale, 2005; Gupta et al., 2019). Also, the effectiveness and safety of these treatments have not been completely investigated yet.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an operative therapeutic strategy in psychiatric clinical practice (Sundsted et al., 2014), mostly used in the management of depression, catatonia, acute dementia, and refractory schizophrenia (Hoirisch-Clapauch et al., 2014). In addition, ECT can have a more effective role than medication in managing psychosis, bipolar disorder, and depression due to its mood-stabilizing properties Medda et al., 2014). Many neurobiological mechanisms, such as neurophysiological and neurochemical alterations in different brain parts, have been reported as mechanisms involved in ECT. Likewise, numerous biological aspects of ECT, including alterations in neurochemicals and gene expression and changing the blood-brain barrier permeability and the immune system, contribute to ECT’s therapeutic effects (Singh & Kar, 2017). There is a chance that patients with treatment-resistant OCD may be spared from invasive operations if an ECT experiment is conducted; however, evidence supporting the efficacy of ECT in treating OCD is still lacking. Former studies focusing on the efficacy of ECT in the treatment of OCD usually were limited to case reports and uncontrolled studies. Also, in most of these reported cases, OCD was present with a comorbid condition particularly depression. Consequently, the majority of investigators believe that ECT should mainly be administered for treatment-resistant OCD patients in the context of major depression (Liu et al., 2014). Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy of ECT in OCD patients without comorbid psychiatric disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted as a pilot study on 12 adult patients (aged over 18 years) with severe OCD referred to a tertiary care hospital for neuropsychological disorders (the name of the canter was disclosed for peer review). Patients were recruited for 12 months from December 2019 to December 2020, and the severity of OCD was scored using the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale (Bülbül et al., 2013). Severe cases of the disease (Yale-Brown test score above 25) were included in the study. The additional inclusion criteria were indications for ECT as determined by an experienced physiatrist based on a lack of response to pharmacotherapy, including an adequate dose of antidepressants and or mood stabilizers with documented efficacy in severe OCD patients (SSRI and clomipramine) for at least 6 months or medical treatment discontinuation due to side effects. The exclusion criteria were having received ECT within 6 months, rapid cycling course of illness, an unstable serious medical condition (for example, cerebral palsy), a history of myocardial infarction in the last 30 days, a history of cerebrovascular disease or aneurysm, and any condition assumed to cause or affect neurocognitive function (such as bipolar disease, depressive disorder, schizophrenia or drug abuse). Also, before ECT, the presence of depressive disorder in these patients was ruled out utilizing the Hamilton questionnaire, and those with comorbid depression were excluded. The patients were also excluded from the study if the clinician found that the patients required, or were better served with other treatment, became significantly clinically worse, or the patients withdrew their consent.

Before starting the treatment, the patient’s age, gender, and level of education, as well as the type of OCD, drug history, and the dose of previously prescribed medications, were recorded in the prepared checklists. Two experienced psychiatrists independently conducted the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) to attain the diagnosis of OCD and ruled out other major mental illnesses by relevant examinations. Ultimately, the most severe and medication-resistant patients (based on Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale) were selected. ECT was performed for all patients according to the standard procedure described below. We completed the Yale-Brown test for all the patients before ECT, on the day after applying ECT, and two months after the final ECT session to evaluate the effect of therapy. Patients provided written informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

Study treatment

The ECT procedure was standardized using the Thymatron System IV device (Somatics, Lake Bluff, Ill.). The stimulation electrodes were placed following the d’Elia method (right unilateral electrode placement) (d’Elia, 1970; Kellner et al., 2010; Welch, 2015). The pulse width during the procedure was fixed at 0.5 ms. The first stimulus dosage was calculated for each patient individually based on her/his age and gender (d’Elia, 1970; First, 1997; Kellner et al., 2010; Welch, 2015).

Treatment was administered three times a week for up to three to four weeks (a minimum of 8 sessions and a maximum of 12 sessions). The number of ECT sessions was chosen due to the previous studies on using ECT for the treatment of OCD patients (Bülbül et al., 2013; Casey & Davis, 1994; Husain et al., 1993; Jenike et al., 1987; Raveendranathan et al., 2012).

Thiopental with a minimum dosage (1.5-2.5 mg/kg IV) was used to induce anesthesia during the ECT sessions. Also, succinylcholine (muscle relaxant) with a dose of 0.5-1.0 mg/kg IV was used while performing ECT. Pulse oximetry was conducted, and oxygen-enriched air was administered to all patients for 1 to 2 minutes before anesthesia and during the treatment.

Patients were not allowed to use their previous medication while receiving the ECT to evaluate the result of using ECT treatment only.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were prescribed for managing patients who experienced mild complications, such as muscle pain or headache, during this study.

Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale

The Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale is the gold standard for evaluating the severity of OCD symptoms (Goodman et al., 1989). The Yale-Brown practical obsession scale, conducted as a semi-structured interview, measures the severity and the type of obsession. With the development of the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive Scale, the accuracy of the current rating scales has been largely improved due to its precise measurement of the severity of OCD symptoms. This scale includes 10 items completed by the clinician, scoring from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (extreme symptoms) with a total score range of 0 to 40. The reliability of this scale (r=0.98), its internal consistency (α=0.98), and test-retest correlation in two-week intervals (r=0.84) were approved in Iran (Rajezi Esfahani et al., 2011) and by previous studies (Goodman et al., 1989). Also, its criterion validity was obtained with Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale as 0.64 and 0.59, respectively (Goodman et al., 1989).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 24 (SPSS Co., Chicago). Mean±SD or median and interquartile range were computed for continuous variables, while numbers and percentages were computed for categorical variables. Yale-Brown scores were analyzed before and after treatment using the Wilcoxon test. Correlation between variables was evaluated using the Spearman test. P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

In this study, 12 patients were studied, of which 6(50%) were men and 6(50%) were women. Six patients (50%) had washing obsession problems, 4(33.3%) had frequent checking obsessions, 1(8.3%) had order obsessions, and 1(8.3%) had comorbidity of checking and washing obsession. Three patients (25%) had a history of behavioral therapy. The demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

.jpg)

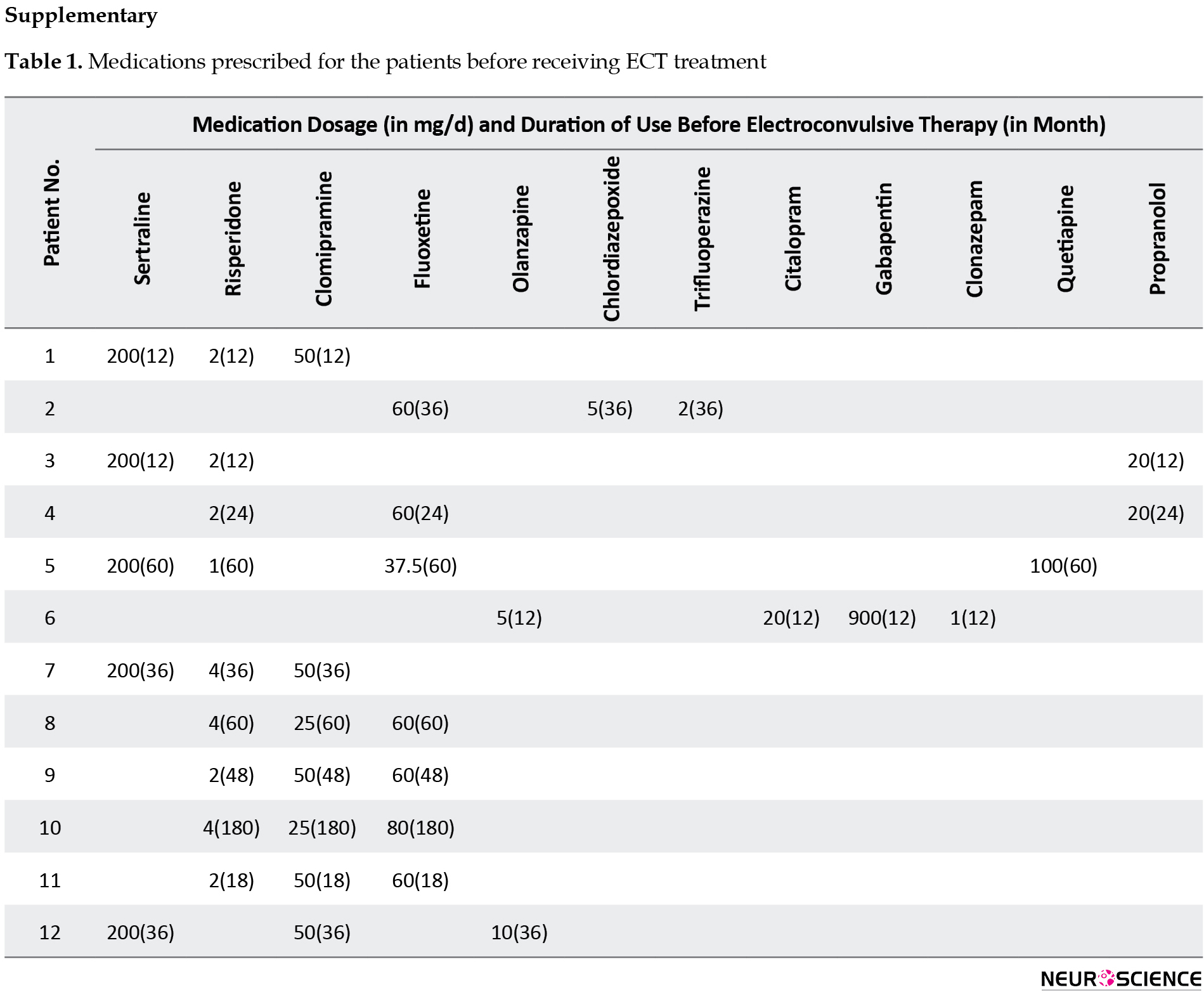

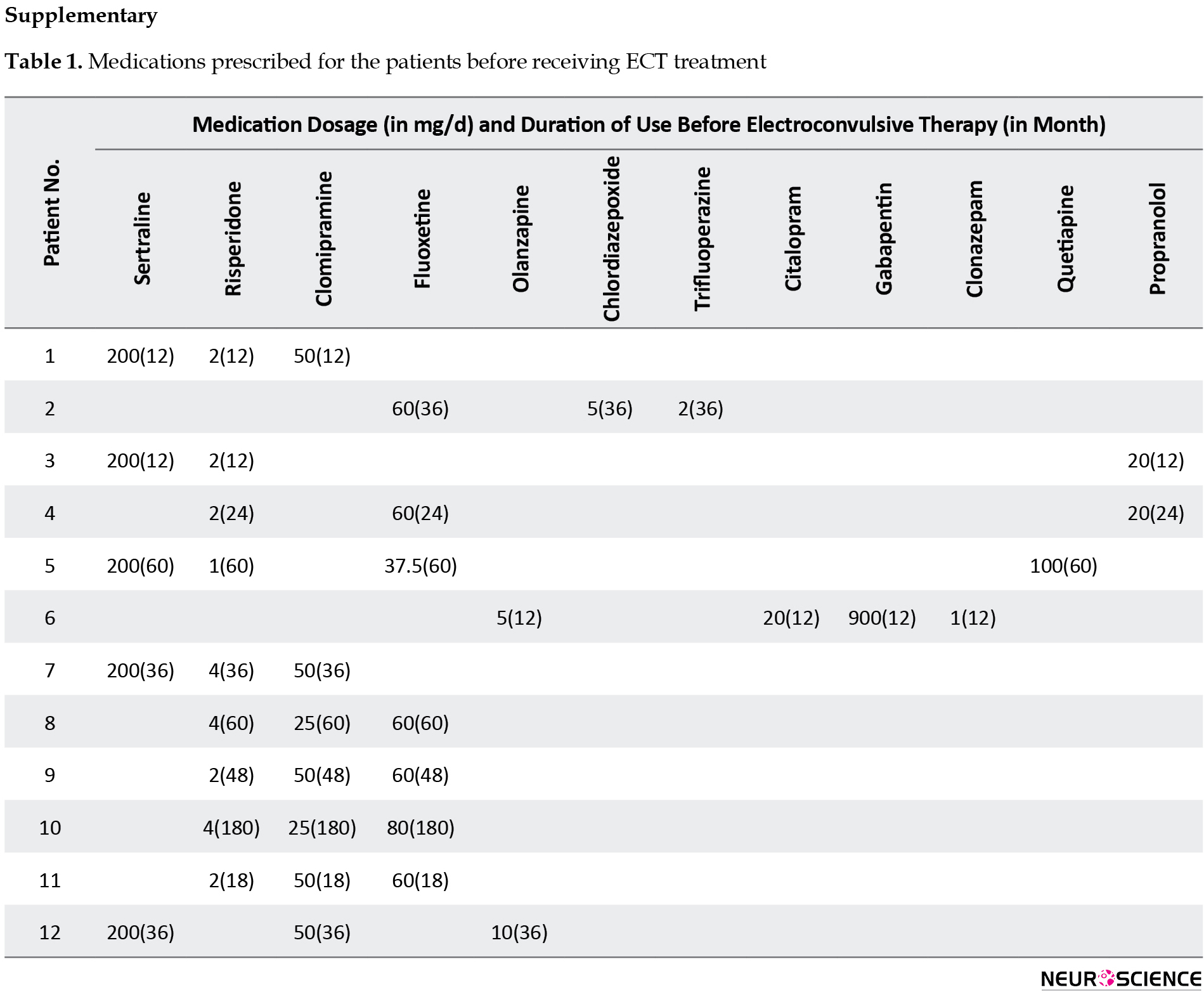

The medications prescribed for patients before ECT are described in Supplementary Table 1.

None of the patients developed significant side effects during or after ECT sessions, and the treatment course was completed for all patients. The median number of ECT sessions was 10 (interquartile range [IQR]: 10-12). The median duration of obsessive-compulsive disorder was 6 years (IQR: 2-15 years).

The Mean±SD of Yale-Brown score of the patients was 28.08±2.50 at baseline, and all 12 patients (100%) started treatment with severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Mean±SD of Yale-Brown score of patients on the day after the treatment sessions was 17.17±3.78, significantly lower than the baseline score (P=0.043). The severity of OCD improved in all patients and reduced to a mild level in 4 patients (33.3%) and a moderate level in 8(66.7%) (Table 2).

.jpg)

Patients’ involvement status was assessed two months after the end of treatment. The Mean±SD of Yale-Brown score slightly increased to 18.08±1.62 (P=0.125), and the severity of OCD in all 12 patients (100%) became moderate. Nevertheless, in none of them, the Yale-Brown score increased to the baseline value in this period (Table 3, Figure 1).

.jpg)

.jpg)

There was a significant negative correlation between the extent of the response to ECT as measured the day after the last ECT session and after two months (r=-0.810, P=0.001). Those with greater immediate response had a greater increase in Yale-Brown score after two months (cases 1, 4, and 5; Table 3).

Assessing the effect of treatment on each type of OCD demonstrated that all types of OCD responded similarly to OCD treatment (Table 4).

.jpg)

4. Discussion

The reports on treating OCD with ECT are contradictory, mostly limited to case reports and uncontrolled studies. Moreover, most researchers believe that ECT should be applied to patients with treatment-resistant OCD, focusing on curing major depression accompanying OCD (Goodman, 1992). As in a study by Xiaohui Liu et al. (2014), the severity of disease in three OCD cases with comorbid depression alleviated and remained stable after ECT treatment at regular follow-up. The evaluations were conducted on Hamilton anxiety scale, Hamilton depression scale, and the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale score. Therefore, we designed this study to investigate patients with treatment-resistant or severe OCD without any psychological comorbidity to prove that ECT might be useful for these patients. In our study, ECT was effective in treating OCD without comorbid psychiatric disorders in both short-term and mid-term evaluations. Some studies reported the data of patients with OCD who responded positively to ECT (Bülbül et al., 2013; Martins-Correia et al., 2021; Raveendranathan et al., 2012). Khanna et al. (1988) reported the short-term anti-obsessional ECT outcomes in 9 OCD cases. Beale et al. (1995) also performed a study on three patients with refractory OCD, which all were treated with ECT leading to significantly improved conditions. Moreover, two female patients experiencing chronic OCD and depression were treated with ECT and responded properly to the treatment (Casey & Davis, 1994; Husain et al., 1993). Maletzky et al. (1994) reported significant improvement in 32 OCD patients after ECT treatment, of whom 19 patients did not have comorbid depression suggesting the benefits of ECT for all OCD patients with or without depression. Also, Bülbül et al. (2013) investigated the effect of ECT on patients with a depressive episode of bipolar disorder and concurrent OCD. They reported that both depression and OCD symptoms were successfully treated with ECT. In a study executed by Martins-Correia et al. (2021), ECT was administered to a patient with refractory OCD, and the patient’s clinical response and functional improvement were significant. Some other case reports also have demonstrated the positive effect of ECT on severe OCD patients (Hanisch et al., 2009; Loi & Bonwick, 2010; Tomruk et al., 2010).

Because of the fear of neurological side effects, ECT for treating OCD was for decades a controversial treatment for treating OCD, but the patient’s acceptance of this treatment has recently increased because the studies support the idea that the benefits of ECT outweigh the disadvantages (Moksnes et al., 2006). Notably, the ECT treatment course was safely completed for all our patients without significant adverse effects. Although ECT is associated with cognitive side effects in some cases (Association, 2008), few studies have performed head-to-head comparisons of the treatment-induced cognitive impairment in medication versus ECT-treated patients. Moreover, it seems that the severity, type, and duration of cognitive dysfunction attributed to ECT treatment reportedly depend on the methods used in ECT administration (McCall., et al., 2000; Sackeim et al., 2007). The most distressing adverse effect of ECT developed in a few cases was the loss, sometimes permanent, of autobiographical memories. Some studies claim that all patients who received ECT experienced some degree of retrograde amnesia (Read & Bentall, 2010). Nevertheless, this side effect is described as a rare complication by most experts (Semkovska & McLoughlin, 2013). The use of bilateral electrode placement was previously reported to be the strongest predictor for understanding whether retrograde amnesia happens in the few months after a complete course of ECT (Kolshus et al, 2017; Lisanby et al., 2000; Sackeim et al., 2007). Although we used bilateral electrode placement in the present study, no adverse event occurred in our patients.

All patients in our study improved after ECT sessions. Nevertheless, previous studies have reported that up to 60% of patients with OCD responded to ECT (Fontenelle et al., 2015). The higher response rate in our study is attributable to some points that should be regarded. It should be noted that the Yale-brown score in some of our patients increased after two months, but it did not reach the baseline value. However, there was a possibility that in longer follow-up duration, the severity of OCD in some patients returned to the baseline status, and the response rate decreased. Furthermore, considering that our study was a pilot study on a small number of patients to highlight the efficacy and safety of ECT in OCD patients, the response rate percentage might not be generalizable to the whole population, and further studies are warranted in this regard. Nevertheless, some specific features of our study, such as completing all ECT sessions by all patients, the inclusion of only severe OCD patients, and exclusion of patients with comorbid psychiatric be other reasons for the higher response rate in our patients. Furthermore, using different OCD severity assessment tools, administration of concurrent pharmacotherapy during ECT sessions, the various definitions of severe and refractory OCD, and different ECT protocols and durations could be another explanation for different response rates among studies (Kadouri et al., 2007; Sheehan et al., 2013; Talaei et al., 2009; Fontenelle et al., 2015).

Although Fontenelle et al. (2015) reviewed the studies on the effect of ECT on OCD patients, there were major limitations in the studies that were included in this review that should be regarded.

As the authors of this review have mentioned, the studies that reported a nonsignificant effect of ECT in the treatment of OCD patients had a vague definition of pharmaco-resistant OCD. Fontenelle et al. explained in the discussion part that OCD patients, who were treated with ECT, have often received inadequate medical treatment before ECT. Moreover, the duration and dosage of these medications are barely reported. Therefore, there is a large possibility that many benign OCD patients have probably been labeled as treatment-resistant and received ECT. Patients in our study had received appropriate pharmacotherapy and had not responded well to these treatments before entering our study as pharmaco-resistant severe OCD cases. For further clarification, the information on pharmacotherapy of the patients before the study is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Some of the OCD patients under treatment in these studies did not complete their course of treatment with ECT due to the fear of possible adverse effects. Therefore, their unsuccessful results may reduce the overall positive results in these studies.

Furthermore, the existence of depression as a comorbid psychiatric condition in OCD cases in these studies could alter the effectiveness of OCD.

Our study has a few limitations. Due to the uncertainty in the effectiveness and safety of ECT in previous studies, as well as low patient acceptance and the fear of adverse effects, conducting the current study with a large sample size was not feasible. However, considering the results of our study, future studies can be performed as multicenter studies and include a larger sample size. Furthermore, we did not include a control group in our study. Therefore, designing future studies with randomized controlled clinical trial design with pharmacological treatment (or other treatments) as a comparison for ECT is warranted. Also, supplementation of ECT with different classes of medication to maintain its positive effects and prevent future OCD relapses can be considered in future studies. Also, future studies can alter the number of ECT sessions in a week or the duration of applying ECT to evaluate and find the best strategies. We also suggest that future studies with larger sample sizes perform subgroup analysis to evaluate the effect of ECT in different subgroups and perform a multivariate regression analysis to find the predictor of a better response.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, the current results show that ECT was a safe and effective therapeutic strategy for patients with treatment-resistant OCD with no comorbid psychiatric disorders in our study. However, further randomized controlled trials are required to validate the efficacy of ECT for OCD treatment before considering it in clinical practice.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. (Code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1398.962)

Funding

The paper was extracted from the thesis of Ali Fakhari-Dehkharghani, Research Center of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and Supervision: Seyed Gholamreza Noorazar; Methodology: Ali Fakhari-Dehkharghani; Investigation, data analysis, writing-original draft, and writing-review & editing: Parnia Pouya; Data collection: Somayyeh Emamizad; Funding acquisition and resources: Seyed Gholamreza Noorazar, Somayyeh Emamizad and Ali Fakhari-Dehkharghani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Abba-Aji, A., Li, D., Hrabok, M., Shalaby, R., Gusnowski, A., & Vuong, W., et al. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and mental health: Prevalence and correlates of new-onset obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a Canadian province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 6986. [PMID] [PMCID]

Albert, U., De Ronchi, D., Maina, G., & Pompili, M. (2019). Suicide risk in obsessive-compulsive disorder and exploration of risk factors: A systematic review. Current Neuropharmacology, 17(8), 681–696. [PMID] [PMCID]

Association, A. P. (2008). The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging (A task force report of the American Psychiatric Association). Washington: C American Psychiatric Pub. [Link]

Beale, M. D., Kellner, C. H., Pritchett, J. T., & Burns, C. M. (1995). ECT for OCD. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 56(2), 81. [Link]

Bülbül, F., Copoglu, U. S., Alpak, G., Unal, A., Tastan, M. F., & Savas, H. A. (2013). Maintenance therapy with electroconvulsive therapy in a patient with a codiagnosis of bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of ECT, 29(2), e21-e22. [PMID]

Carrillo-Ruiz, J. D. (2012). Topics in neuromodulation treatment. London: IntechOpen. [Link]

Casey, D. A., & Davis, M. H. (1994). Obsessive-compulsive disorder responsive to electroconvulsive therapy in an elderly woman. Southern Medical Journal, 87(8), 862-864. [PMID]

d’Elia, G. (1970). Unilateral electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 215, 1–98. [PMID]

de Koning, P. P., Figee, M., van den Munckhof, P., Schuurman, P. R., & Denys, D. (2011). Current status of deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A clinical review of different targets. Current Psychiatry Reports, 13(4), 274-282. [PMID]

Denys, D. (2006). Pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(2), 553-584. [DOI:10.1016/j.psc.2006.02.013] [PMID]

Fineberg, N. A., & Gale, T. M. (2005). Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 8(1), 107–129. [PMID]

Fineberg, N. A., Hollander, E., Pallanti, S., Walitza, S., Grünblatt, E., & Dell'Osso, B. M., et al. (2020). Clinical advances in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A position statement by the International College of Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 35(4), 173-193. [PMID] [PMCID]

First, M. B., & Gibbon, M. (2004). The structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II disorders. M. J. Hilsenroth, & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment (pp. 136). New York: Wiley.

Fontenelle, L. F., Coutinho, E. S., Lins-Martins, N. M., Fitzgerald, P. B., Fujiwara, H., & Yücel, M. (2015). Electroconvulsive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(7), 949–957. [PMID]

Fontenelle, L. F., Nascimento, A. L., Mendlowicz, M. V., Shavitt, R. G., & Versiani, M. (2007). An update on the pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 8(5), 563-583. [PMID]

Fullana, M. A., Vilagut, G., Rojas-Farreras, S., Mataix-Cols, D., de Graaf, R., & Demyttenaere, K., et al. (2010). Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions in the general population: Results from an epidemiological study in six European countries. Journal of Affective Disorders, 124(3), 291-299. [PMID]

Goodman, W. K. (1992). Pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. In I. Hand, W. K., Goodman, & U. Evers (Eds.), Zwangsstörungen / Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders. Die Reihe dupbar med communication wird / Series dupbar med communication (pp 141–151). Berlin: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-77608-3_13]

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Delgado, P., & Heninger, G. R., etal. (1989). The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: II. Validity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1012-1016. [PMID]

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R. L., & Hill, C. L., et al. (1989). The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1006-1011. [PMID]

Gupta, A., Shepard, M. J., Xu, Z., Maiti, T., Martinez-Moreno, N., & Silverman, J., et al. (2019). An international radiosurgery research foundation multicenter retrospective study of gamma ventral capsulotomy for obsessive compulsive disorder. Neurosurgery, 85(6), 808-816. [PMID]

Hanisch, F., Friedemann, J., Piro, J., & Gutmann, P. (2009). Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy for comorbid pharmacotherapy-refractory obsessive-compulsive and schizoaffective disorder. European Journal of Medical Research, 14(8), 367-368. [PMID] [PMCID]

Hoirisch-Clapauch, S., Mezzasalma, M. A., & Nardi, A. E. (2014). Pivotal role of tissue plasminogen activator in the mechanism of action of electroconvulsive therapy. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(2), 99-105. [PMID]

Husain, M. M., Lewis, S. F., & Thornton, W. L. (1993). Maintenance ECT for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(12), 1899–1900. [PMID]

Jenike, M. A., Baer, L., & Minichiello, W. E. (1987). Somatic treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 28(3), 250-263. [DOI:10.1016/0010-440X(87)90032-0]

Kadouri, A., Corruble, E., & Falissard, B. (2007). The improved Clinical Global Impression Scale (iCGI): Development and validation in depression. BMC Psychiatry, 7, 7. [PMCID]

Kellner, C. H., Knapp, R., Husain, M. M., Rasmussen, K., Sampson, S., & Cullum, M., et al. (2010). Bifrontal, bitemporal and right unilateral electrode placement in ECT: Randomised trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(3), 226-234. [PMID]

Khanna, S., Gangadhar, B. N., Sinha, V., Rajendra, P. N., & Channabasavanna, S. M. (1988). Electroconvulsive therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Convulsive Therapy, 4(4), 314–320. [PMID]

Kolshus, E., Jelovac, A., & McLoughlin, D. M. (2017). Bitemporal v. high-dose right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychological Medicine, 47(3), 518-530. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291716002737] [PMID]

Lisanby, S. H., Maddox, J. H., Prudic, J., Devanand, D. P., & Sackeim, H. A. (2000). The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on memory of autobiographical and public events. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(6), 581-590. [PMID]

Liu, X., Cui, H., Wei, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, K., & Wang, C., et al. (2014). Electroconvulsive therapy on severe obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbid depressive symptoms. Psychiatry Investigation, 11(2), 210-213. [PMID] [PMCID]

Loi, S., & Bonwick, R. (2010). Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment of late-onset obsessive compulsive disorder. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(5), 830-831. [PMID]

Maletzky, B., McFarland, B., & Burt, A. (1994). Refractory obsessive compulsive disorder and ECT. Convulsive Therapy, 10(1), 34–42. [PMID]

Mancebo, M. C., Greenberg, B., Grant, J. E., Pinto, A., Eisen, J. L., & Dyck, I., et al. (2008). Correlates of occupational disability in a clinical sample of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(1), 43-50. [PMID] [PMCID]

Marazziti, D., & Consoli, G. (2010). Treatment strategies for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 11(3), 331-343. [PMID]

Martins-Correia, J., Rodrigues-Silva, N., & Nunes, S. (2021). Electroconvulsive therapy in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: A case report. The Journal of ECT, 37(2), e17-e19. [PMID]

McCall, W. V., Reboussin, D. M., Weiner, R. D., & Sackeim, H. A. (2000). Titrated moderately suprathreshold vs fixed high-dose right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy: Acute antidepressant and cognitive effects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(5), 438-444. [PMID]

Medda, P., Toni, C., & Perugi, G. (2014). The mood-stabilizing effects of electroconvulsive therapy. The Journal of ECT, 30(4), 275-282. [PMID]

Moksnes, K. M., Vatnaland, T., Eri, B., & Torvik, N. H. (2006).[Electroconvulsive therapy in the Ullevaal region of Oslo 1988-2002 (Norwegian]. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening: Tidsskrift for Praktisk Medicin, ny Raekke, 126(13), 1750–1753. [PMID]

Raveendranathan, D., Srinivasaraju, R., Ratheesh, A., Math, S. B., & Reddy, Y. C. (2012).Treatment-refractory OCD responding to maintenance electroconvulsive therapy. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 24(2), E16-E17. [PMID]

Read, J., & Bentall, R. (2010). The effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy: A literature review. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 19(4), 333–347. [PMID]

Rosario-Campos, M. C., Miguel, E. C., Quatrano, S., Chacon, P., Ferrao, Y., & Findley, D., et al. (2006). The Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS): An instrument for assessing obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Molecular Psychiatry, 11(5), 495-504. [PMID]

Sackeim, H. A., Prudic, J., Devanand, D. P., Nobler, M. S., Lisanby, S. H., & Peyser, S., et al. (2000). A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of bilateral and right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy at different stimulus intensities. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(5), 425-434. [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.425] [PMID]

Sackeim, H. A., Prudic, J., Fuller, R., Keilp, J., Lavori, P. W., & Olfson, M. (2007). The cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy in community settings. Neuropsychopharmacology, 32(1), 244-254. [DOI:10.1038/sj.npp.1301180] [PMID]

Semkovska, M., & McLoughlin, D. M. (2013). Measuring retrograde autobiographical amnesia following electroconvulsive therapy: Historical perspective and current issues. The Journal of ECT, 29(2), 127-133. [PMID]

Esfahani, S., Motaghipour, Y., Kamkari, K., Zahiredin, A., & Janbozorgi, M. (2012). [Reliability and validity of the Persian version of the yale-brown obsessive-compulsive scale (Y-BOCS). (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 17(4), 297-303. [Link]

Sheehan, J. P., Patterson, G., Schlesinger, D., & Xu, Z. (2013). Gamma knife surgery anterior capsulotomy for severe and refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Neurosurgery, 119(5), 1112-1118. [PMID]

Sheth, S. A., Neal, J., Tangherlini, F., Mian, M. K., Gentil, A., & Cosgrove, G. R., et al. (2013). Limbic system surgery for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: A prospective long-term follow-up of 64 patients. Journal of Neurosurgery, 118(3), 491-497. [PMID]

Simpson, H. B. (2009). Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 2, 527–543. [PMID]

Simpson, H. B., Foa, E. B., Liebowitz, M. R., Huppert, J. D., Cahill, S., & Maher, M. J., et al. (2013). Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs risperidone for augmenting serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(11), 1190-1199. [PMID] [PMCID]

Singh, A., & Kar, S. K. (2017). How electroconvulsive therapy works?: Understanding the neurobiological mechanisms. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 15(3), 210–221. [PMID]

Sundsted, K. K., Burton, M. C., Shah, R., & Lapid, M. I. (2014).Preanesthesia medical evaluation for electroconvulsive therapy: A review of the literature. The Journal of ECT, 30(1), 35-42. [PMID]

Talaei, A., Mortezania, M., Jafarzadeh, F. S., Saghebi, A., & Rezaei, A. A. (2009). Dramatic response of resistant obsessive compulsive disorder to repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation on right supplementary motor area (Case Report). Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences,34(4), 295-298. [Link]

Tomruk, N. B., Saatcioglu, O., Ugurlu, E., & Hacioglu, M. (2010). ECT use in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni-Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20(2), 167-170. [DOI:10.1080/10177833.2010.11790653]

Stern, T. A., Fava, M., Wilens, T. E., & Rosenbaum, J. F. (2015). Massachusetts general hospital psychopharmacology and neurotherapeutics. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences. [Link]

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is an incapacitating and long-standing neuropsychiatric disorder prevalent in roughly 2% of the population (Fullana et al., 2010). Furthermore, remarkable growth in OCD prevalence has been reported during the COVID-19 pandemic (Abba-Aji et al., 2020). Contamination (washing), checking, symmetry (ordering/arranging), ruminations (intrusive thoughts), sexual/religious, and hoarding are the most common aspects of OCD symptoms (Rosario-Campos et al., 2006), which can cause social and occupational problems (Mancebo et al., 2008) and ultimately high suicidal thoughts and attempts in severe cases (Albert, et al., 2019).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and clomipramine are mainly used to treat OCD (Marazziti & Consoli, 2010). These medications prevent the reabsorption or secretion of serotonin in the synaptic space and increase the concentration of serotonin in the synapses. It is demonstrated that increasing serotonin levels in the frontal lobe alleviate OCD symptoms. Moreover, olanzapine and risperidone are antipsychotic medications prescribed for treating OCD symptoms to enhance SSRI effects. Studies show that these medications have partially or completely suboptimal efficacy in OCD patients, mainly in severe cases (in 40% to 60% of patients). Treatment-resistant OCD subjects are patients who receive an adequate trial of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (clomipramine or SSRI) and do not respond or show unsatisfactory response to treatment; this condition accounts for 40%-50% of all OCD patients. The definition of treatment-refractory OCD may imply a greater degree of resistance to interventions, including non-respond to SSRIs/clomipramine, augmentation strategies, and behavioral intervention (Fontenelle, Nascimento, Mendlowicz, Shavitt, & Versiani, 2007; Simpson et al., 2013). Therefore, developing novel evidence-based strategies for managing treatment-resistant OCD patients is necessary (Simpson, 2009). Evolving therapies for severe and treatment-resistant OCD comprise psychotherapies, novel pharmacotherapies, immunological therapies, pharmacogenetics, non-invasive neurostimulation, and invasive neurostimulation (Fineberg et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the evidence is limited for most of these novel therapeutic strategies (Carrillo, 2012). Despite the considerable improvement of patients using invasive neurostimulation therapies such as deep brain stimulation (de Koning et al. , 2011), limbic system surgery (Sheth et al., 2013), and ablative neurosurgery, they cannot be considered the first choice of treatment due to the need for general anesthesia and high costs (Denys, 2006; Fineberg & Gale, 2005; Gupta et al., 2019). Also, the effectiveness and safety of these treatments have not been completely investigated yet.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an operative therapeutic strategy in psychiatric clinical practice (Sundsted et al., 2014), mostly used in the management of depression, catatonia, acute dementia, and refractory schizophrenia (Hoirisch-Clapauch et al., 2014). In addition, ECT can have a more effective role than medication in managing psychosis, bipolar disorder, and depression due to its mood-stabilizing properties Medda et al., 2014). Many neurobiological mechanisms, such as neurophysiological and neurochemical alterations in different brain parts, have been reported as mechanisms involved in ECT. Likewise, numerous biological aspects of ECT, including alterations in neurochemicals and gene expression and changing the blood-brain barrier permeability and the immune system, contribute to ECT’s therapeutic effects (Singh & Kar, 2017). There is a chance that patients with treatment-resistant OCD may be spared from invasive operations if an ECT experiment is conducted; however, evidence supporting the efficacy of ECT in treating OCD is still lacking. Former studies focusing on the efficacy of ECT in the treatment of OCD usually were limited to case reports and uncontrolled studies. Also, in most of these reported cases, OCD was present with a comorbid condition particularly depression. Consequently, the majority of investigators believe that ECT should mainly be administered for treatment-resistant OCD patients in the context of major depression (Liu et al., 2014). Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy of ECT in OCD patients without comorbid psychiatric disorders.

2. Materials and Methods

This quasi-experimental study was conducted as a pilot study on 12 adult patients (aged over 18 years) with severe OCD referred to a tertiary care hospital for neuropsychological disorders (the name of the canter was disclosed for peer review). Patients were recruited for 12 months from December 2019 to December 2020, and the severity of OCD was scored using the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale (Bülbül et al., 2013). Severe cases of the disease (Yale-Brown test score above 25) were included in the study. The additional inclusion criteria were indications for ECT as determined by an experienced physiatrist based on a lack of response to pharmacotherapy, including an adequate dose of antidepressants and or mood stabilizers with documented efficacy in severe OCD patients (SSRI and clomipramine) for at least 6 months or medical treatment discontinuation due to side effects. The exclusion criteria were having received ECT within 6 months, rapid cycling course of illness, an unstable serious medical condition (for example, cerebral palsy), a history of myocardial infarction in the last 30 days, a history of cerebrovascular disease or aneurysm, and any condition assumed to cause or affect neurocognitive function (such as bipolar disease, depressive disorder, schizophrenia or drug abuse). Also, before ECT, the presence of depressive disorder in these patients was ruled out utilizing the Hamilton questionnaire, and those with comorbid depression were excluded. The patients were also excluded from the study if the clinician found that the patients required, or were better served with other treatment, became significantly clinically worse, or the patients withdrew their consent.

Before starting the treatment, the patient’s age, gender, and level of education, as well as the type of OCD, drug history, and the dose of previously prescribed medications, were recorded in the prepared checklists. Two experienced psychiatrists independently conducted the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) to attain the diagnosis of OCD and ruled out other major mental illnesses by relevant examinations. Ultimately, the most severe and medication-resistant patients (based on Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale) were selected. ECT was performed for all patients according to the standard procedure described below. We completed the Yale-Brown test for all the patients before ECT, on the day after applying ECT, and two months after the final ECT session to evaluate the effect of therapy. Patients provided written informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

Study treatment

The ECT procedure was standardized using the Thymatron System IV device (Somatics, Lake Bluff, Ill.). The stimulation electrodes were placed following the d’Elia method (right unilateral electrode placement) (d’Elia, 1970; Kellner et al., 2010; Welch, 2015). The pulse width during the procedure was fixed at 0.5 ms. The first stimulus dosage was calculated for each patient individually based on her/his age and gender (d’Elia, 1970; First, 1997; Kellner et al., 2010; Welch, 2015).

Treatment was administered three times a week for up to three to four weeks (a minimum of 8 sessions and a maximum of 12 sessions). The number of ECT sessions was chosen due to the previous studies on using ECT for the treatment of OCD patients (Bülbül et al., 2013; Casey & Davis, 1994; Husain et al., 1993; Jenike et al., 1987; Raveendranathan et al., 2012).

Thiopental with a minimum dosage (1.5-2.5 mg/kg IV) was used to induce anesthesia during the ECT sessions. Also, succinylcholine (muscle relaxant) with a dose of 0.5-1.0 mg/kg IV was used while performing ECT. Pulse oximetry was conducted, and oxygen-enriched air was administered to all patients for 1 to 2 minutes before anesthesia and during the treatment.

Patients were not allowed to use their previous medication while receiving the ECT to evaluate the result of using ECT treatment only.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were prescribed for managing patients who experienced mild complications, such as muscle pain or headache, during this study.

Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale

The Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale is the gold standard for evaluating the severity of OCD symptoms (Goodman et al., 1989). The Yale-Brown practical obsession scale, conducted as a semi-structured interview, measures the severity and the type of obsession. With the development of the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive Scale, the accuracy of the current rating scales has been largely improved due to its precise measurement of the severity of OCD symptoms. This scale includes 10 items completed by the clinician, scoring from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (extreme symptoms) with a total score range of 0 to 40. The reliability of this scale (r=0.98), its internal consistency (α=0.98), and test-retest correlation in two-week intervals (r=0.84) were approved in Iran (Rajezi Esfahani et al., 2011) and by previous studies (Goodman et al., 1989). Also, its criterion validity was obtained with Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale as 0.64 and 0.59, respectively (Goodman et al., 1989).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 24 (SPSS Co., Chicago). Mean±SD or median and interquartile range were computed for continuous variables, while numbers and percentages were computed for categorical variables. Yale-Brown scores were analyzed before and after treatment using the Wilcoxon test. Correlation between variables was evaluated using the Spearman test. P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

In this study, 12 patients were studied, of which 6(50%) were men and 6(50%) were women. Six patients (50%) had washing obsession problems, 4(33.3%) had frequent checking obsessions, 1(8.3%) had order obsessions, and 1(8.3%) had comorbidity of checking and washing obsession. Three patients (25%) had a history of behavioral therapy. The demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

.jpg)

The medications prescribed for patients before ECT are described in Supplementary Table 1.

None of the patients developed significant side effects during or after ECT sessions, and the treatment course was completed for all patients. The median number of ECT sessions was 10 (interquartile range [IQR]: 10-12). The median duration of obsessive-compulsive disorder was 6 years (IQR: 2-15 years).

The Mean±SD of Yale-Brown score of the patients was 28.08±2.50 at baseline, and all 12 patients (100%) started treatment with severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Mean±SD of Yale-Brown score of patients on the day after the treatment sessions was 17.17±3.78, significantly lower than the baseline score (P=0.043). The severity of OCD improved in all patients and reduced to a mild level in 4 patients (33.3%) and a moderate level in 8(66.7%) (Table 2).

.jpg)

Patients’ involvement status was assessed two months after the end of treatment. The Mean±SD of Yale-Brown score slightly increased to 18.08±1.62 (P=0.125), and the severity of OCD in all 12 patients (100%) became moderate. Nevertheless, in none of them, the Yale-Brown score increased to the baseline value in this period (Table 3, Figure 1).

.jpg)

.jpg)

There was a significant negative correlation between the extent of the response to ECT as measured the day after the last ECT session and after two months (r=-0.810, P=0.001). Those with greater immediate response had a greater increase in Yale-Brown score after two months (cases 1, 4, and 5; Table 3).

Assessing the effect of treatment on each type of OCD demonstrated that all types of OCD responded similarly to OCD treatment (Table 4).

.jpg)

4. Discussion

The reports on treating OCD with ECT are contradictory, mostly limited to case reports and uncontrolled studies. Moreover, most researchers believe that ECT should be applied to patients with treatment-resistant OCD, focusing on curing major depression accompanying OCD (Goodman, 1992). As in a study by Xiaohui Liu et al. (2014), the severity of disease in three OCD cases with comorbid depression alleviated and remained stable after ECT treatment at regular follow-up. The evaluations were conducted on Hamilton anxiety scale, Hamilton depression scale, and the Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale score. Therefore, we designed this study to investigate patients with treatment-resistant or severe OCD without any psychological comorbidity to prove that ECT might be useful for these patients. In our study, ECT was effective in treating OCD without comorbid psychiatric disorders in both short-term and mid-term evaluations. Some studies reported the data of patients with OCD who responded positively to ECT (Bülbül et al., 2013; Martins-Correia et al., 2021; Raveendranathan et al., 2012). Khanna et al. (1988) reported the short-term anti-obsessional ECT outcomes in 9 OCD cases. Beale et al. (1995) also performed a study on three patients with refractory OCD, which all were treated with ECT leading to significantly improved conditions. Moreover, two female patients experiencing chronic OCD and depression were treated with ECT and responded properly to the treatment (Casey & Davis, 1994; Husain et al., 1993). Maletzky et al. (1994) reported significant improvement in 32 OCD patients after ECT treatment, of whom 19 patients did not have comorbid depression suggesting the benefits of ECT for all OCD patients with or without depression. Also, Bülbül et al. (2013) investigated the effect of ECT on patients with a depressive episode of bipolar disorder and concurrent OCD. They reported that both depression and OCD symptoms were successfully treated with ECT. In a study executed by Martins-Correia et al. (2021), ECT was administered to a patient with refractory OCD, and the patient’s clinical response and functional improvement were significant. Some other case reports also have demonstrated the positive effect of ECT on severe OCD patients (Hanisch et al., 2009; Loi & Bonwick, 2010; Tomruk et al., 2010).

Because of the fear of neurological side effects, ECT for treating OCD was for decades a controversial treatment for treating OCD, but the patient’s acceptance of this treatment has recently increased because the studies support the idea that the benefits of ECT outweigh the disadvantages (Moksnes et al., 2006). Notably, the ECT treatment course was safely completed for all our patients without significant adverse effects. Although ECT is associated with cognitive side effects in some cases (Association, 2008), few studies have performed head-to-head comparisons of the treatment-induced cognitive impairment in medication versus ECT-treated patients. Moreover, it seems that the severity, type, and duration of cognitive dysfunction attributed to ECT treatment reportedly depend on the methods used in ECT administration (McCall., et al., 2000; Sackeim et al., 2007). The most distressing adverse effect of ECT developed in a few cases was the loss, sometimes permanent, of autobiographical memories. Some studies claim that all patients who received ECT experienced some degree of retrograde amnesia (Read & Bentall, 2010). Nevertheless, this side effect is described as a rare complication by most experts (Semkovska & McLoughlin, 2013). The use of bilateral electrode placement was previously reported to be the strongest predictor for understanding whether retrograde amnesia happens in the few months after a complete course of ECT (Kolshus et al, 2017; Lisanby et al., 2000; Sackeim et al., 2007). Although we used bilateral electrode placement in the present study, no adverse event occurred in our patients.

All patients in our study improved after ECT sessions. Nevertheless, previous studies have reported that up to 60% of patients with OCD responded to ECT (Fontenelle et al., 2015). The higher response rate in our study is attributable to some points that should be regarded. It should be noted that the Yale-brown score in some of our patients increased after two months, but it did not reach the baseline value. However, there was a possibility that in longer follow-up duration, the severity of OCD in some patients returned to the baseline status, and the response rate decreased. Furthermore, considering that our study was a pilot study on a small number of patients to highlight the efficacy and safety of ECT in OCD patients, the response rate percentage might not be generalizable to the whole population, and further studies are warranted in this regard. Nevertheless, some specific features of our study, such as completing all ECT sessions by all patients, the inclusion of only severe OCD patients, and exclusion of patients with comorbid psychiatric be other reasons for the higher response rate in our patients. Furthermore, using different OCD severity assessment tools, administration of concurrent pharmacotherapy during ECT sessions, the various definitions of severe and refractory OCD, and different ECT protocols and durations could be another explanation for different response rates among studies (Kadouri et al., 2007; Sheehan et al., 2013; Talaei et al., 2009; Fontenelle et al., 2015).

Although Fontenelle et al. (2015) reviewed the studies on the effect of ECT on OCD patients, there were major limitations in the studies that were included in this review that should be regarded.

As the authors of this review have mentioned, the studies that reported a nonsignificant effect of ECT in the treatment of OCD patients had a vague definition of pharmaco-resistant OCD. Fontenelle et al. explained in the discussion part that OCD patients, who were treated with ECT, have often received inadequate medical treatment before ECT. Moreover, the duration and dosage of these medications are barely reported. Therefore, there is a large possibility that many benign OCD patients have probably been labeled as treatment-resistant and received ECT. Patients in our study had received appropriate pharmacotherapy and had not responded well to these treatments before entering our study as pharmaco-resistant severe OCD cases. For further clarification, the information on pharmacotherapy of the patients before the study is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Some of the OCD patients under treatment in these studies did not complete their course of treatment with ECT due to the fear of possible adverse effects. Therefore, their unsuccessful results may reduce the overall positive results in these studies.

Furthermore, the existence of depression as a comorbid psychiatric condition in OCD cases in these studies could alter the effectiveness of OCD.

Our study has a few limitations. Due to the uncertainty in the effectiveness and safety of ECT in previous studies, as well as low patient acceptance and the fear of adverse effects, conducting the current study with a large sample size was not feasible. However, considering the results of our study, future studies can be performed as multicenter studies and include a larger sample size. Furthermore, we did not include a control group in our study. Therefore, designing future studies with randomized controlled clinical trial design with pharmacological treatment (or other treatments) as a comparison for ECT is warranted. Also, supplementation of ECT with different classes of medication to maintain its positive effects and prevent future OCD relapses can be considered in future studies. Also, future studies can alter the number of ECT sessions in a week or the duration of applying ECT to evaluate and find the best strategies. We also suggest that future studies with larger sample sizes perform subgroup analysis to evaluate the effect of ECT in different subgroups and perform a multivariate regression analysis to find the predictor of a better response.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, the current results show that ECT was a safe and effective therapeutic strategy for patients with treatment-resistant OCD with no comorbid psychiatric disorders in our study. However, further randomized controlled trials are required to validate the efficacy of ECT for OCD treatment before considering it in clinical practice.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. (Code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1398.962)

Funding

The paper was extracted from the thesis of Ali Fakhari-Dehkharghani, Research Center of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and Supervision: Seyed Gholamreza Noorazar; Methodology: Ali Fakhari-Dehkharghani; Investigation, data analysis, writing-original draft, and writing-review & editing: Parnia Pouya; Data collection: Somayyeh Emamizad; Funding acquisition and resources: Seyed Gholamreza Noorazar, Somayyeh Emamizad and Ali Fakhari-Dehkharghani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Abba-Aji, A., Li, D., Hrabok, M., Shalaby, R., Gusnowski, A., & Vuong, W., et al. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and mental health: Prevalence and correlates of new-onset obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a Canadian province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 6986. [PMID] [PMCID]

Albert, U., De Ronchi, D., Maina, G., & Pompili, M. (2019). Suicide risk in obsessive-compulsive disorder and exploration of risk factors: A systematic review. Current Neuropharmacology, 17(8), 681–696. [PMID] [PMCID]

Association, A. P. (2008). The practice of electroconvulsive therapy: recommendations for treatment, training, and privileging (A task force report of the American Psychiatric Association). Washington: C American Psychiatric Pub. [Link]

Beale, M. D., Kellner, C. H., Pritchett, J. T., & Burns, C. M. (1995). ECT for OCD. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 56(2), 81. [Link]

Bülbül, F., Copoglu, U. S., Alpak, G., Unal, A., Tastan, M. F., & Savas, H. A. (2013). Maintenance therapy with electroconvulsive therapy in a patient with a codiagnosis of bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of ECT, 29(2), e21-e22. [PMID]

Carrillo-Ruiz, J. D. (2012). Topics in neuromodulation treatment. London: IntechOpen. [Link]

Casey, D. A., & Davis, M. H. (1994). Obsessive-compulsive disorder responsive to electroconvulsive therapy in an elderly woman. Southern Medical Journal, 87(8), 862-864. [PMID]

d’Elia, G. (1970). Unilateral electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 215, 1–98. [PMID]

de Koning, P. P., Figee, M., van den Munckhof, P., Schuurman, P. R., & Denys, D. (2011). Current status of deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A clinical review of different targets. Current Psychiatry Reports, 13(4), 274-282. [PMID]

Denys, D. (2006). Pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(2), 553-584. [DOI:10.1016/j.psc.2006.02.013] [PMID]

Fineberg, N. A., & Gale, T. M. (2005). Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 8(1), 107–129. [PMID]

Fineberg, N. A., Hollander, E., Pallanti, S., Walitza, S., Grünblatt, E., & Dell'Osso, B. M., et al. (2020). Clinical advances in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A position statement by the International College of Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 35(4), 173-193. [PMID] [PMCID]

First, M. B., & Gibbon, M. (2004). The structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II disorders. M. J. Hilsenroth, & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment (pp. 136). New York: Wiley.

Fontenelle, L. F., Coutinho, E. S., Lins-Martins, N. M., Fitzgerald, P. B., Fujiwara, H., & Yücel, M. (2015). Electroconvulsive therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(7), 949–957. [PMID]

Fontenelle, L. F., Nascimento, A. L., Mendlowicz, M. V., Shavitt, R. G., & Versiani, M. (2007). An update on the pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 8(5), 563-583. [PMID]

Fullana, M. A., Vilagut, G., Rojas-Farreras, S., Mataix-Cols, D., de Graaf, R., & Demyttenaere, K., et al. (2010). Obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions in the general population: Results from an epidemiological study in six European countries. Journal of Affective Disorders, 124(3), 291-299. [PMID]

Goodman, W. K. (1992). Pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. In I. Hand, W. K., Goodman, & U. Evers (Eds.), Zwangsstörungen / Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders. Die Reihe dupbar med communication wird / Series dupbar med communication (pp 141–151). Berlin: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-77608-3_13]

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Delgado, P., & Heninger, G. R., etal. (1989). The yale-brown obsessive compulsive scale: II. Validity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1012-1016. [PMID]

Goodman, W. K., Price, L. H., Rasmussen, S. A., Mazure, C., Fleischmann, R. L., & Hill, C. L., et al. (1989). The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(11), 1006-1011. [PMID]

Gupta, A., Shepard, M. J., Xu, Z., Maiti, T., Martinez-Moreno, N., & Silverman, J., et al. (2019). An international radiosurgery research foundation multicenter retrospective study of gamma ventral capsulotomy for obsessive compulsive disorder. Neurosurgery, 85(6), 808-816. [PMID]

Hanisch, F., Friedemann, J., Piro, J., & Gutmann, P. (2009). Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy for comorbid pharmacotherapy-refractory obsessive-compulsive and schizoaffective disorder. European Journal of Medical Research, 14(8), 367-368. [PMID] [PMCID]

Hoirisch-Clapauch, S., Mezzasalma, M. A., & Nardi, A. E. (2014). Pivotal role of tissue plasminogen activator in the mechanism of action of electroconvulsive therapy. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(2), 99-105. [PMID]

Husain, M. M., Lewis, S. F., & Thornton, W. L. (1993). Maintenance ECT for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(12), 1899–1900. [PMID]

Jenike, M. A., Baer, L., & Minichiello, W. E. (1987). Somatic treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 28(3), 250-263. [DOI:10.1016/0010-440X(87)90032-0]

Kadouri, A., Corruble, E., & Falissard, B. (2007). The improved Clinical Global Impression Scale (iCGI): Development and validation in depression. BMC Psychiatry, 7, 7. [PMCID]

Kellner, C. H., Knapp, R., Husain, M. M., Rasmussen, K., Sampson, S., & Cullum, M., et al. (2010). Bifrontal, bitemporal and right unilateral electrode placement in ECT: Randomised trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(3), 226-234. [PMID]

Khanna, S., Gangadhar, B. N., Sinha, V., Rajendra, P. N., & Channabasavanna, S. M. (1988). Electroconvulsive therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Convulsive Therapy, 4(4), 314–320. [PMID]

Kolshus, E., Jelovac, A., & McLoughlin, D. M. (2017). Bitemporal v. high-dose right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychological Medicine, 47(3), 518-530. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291716002737] [PMID]

Lisanby, S. H., Maddox, J. H., Prudic, J., Devanand, D. P., & Sackeim, H. A. (2000). The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on memory of autobiographical and public events. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(6), 581-590. [PMID]

Liu, X., Cui, H., Wei, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, K., & Wang, C., et al. (2014). Electroconvulsive therapy on severe obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbid depressive symptoms. Psychiatry Investigation, 11(2), 210-213. [PMID] [PMCID]

Loi, S., & Bonwick, R. (2010). Electroconvulsive therapy for treatment of late-onset obsessive compulsive disorder. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(5), 830-831. [PMID]

Maletzky, B., McFarland, B., & Burt, A. (1994). Refractory obsessive compulsive disorder and ECT. Convulsive Therapy, 10(1), 34–42. [PMID]

Mancebo, M. C., Greenberg, B., Grant, J. E., Pinto, A., Eisen, J. L., & Dyck, I., et al. (2008). Correlates of occupational disability in a clinical sample of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(1), 43-50. [PMID] [PMCID]

Marazziti, D., & Consoli, G. (2010). Treatment strategies for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy, 11(3), 331-343. [PMID]

Martins-Correia, J., Rodrigues-Silva, N., & Nunes, S. (2021). Electroconvulsive therapy in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: A case report. The Journal of ECT, 37(2), e17-e19. [PMID]

McCall, W. V., Reboussin, D. M., Weiner, R. D., & Sackeim, H. A. (2000). Titrated moderately suprathreshold vs fixed high-dose right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy: Acute antidepressant and cognitive effects. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(5), 438-444. [PMID]

Medda, P., Toni, C., & Perugi, G. (2014). The mood-stabilizing effects of electroconvulsive therapy. The Journal of ECT, 30(4), 275-282. [PMID]

Moksnes, K. M., Vatnaland, T., Eri, B., & Torvik, N. H. (2006).[Electroconvulsive therapy in the Ullevaal region of Oslo 1988-2002 (Norwegian]. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening: Tidsskrift for Praktisk Medicin, ny Raekke, 126(13), 1750–1753. [PMID]

Raveendranathan, D., Srinivasaraju, R., Ratheesh, A., Math, S. B., & Reddy, Y. C. (2012).Treatment-refractory OCD responding to maintenance electroconvulsive therapy. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 24(2), E16-E17. [PMID]

Read, J., & Bentall, R. (2010). The effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy: A literature review. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, 19(4), 333–347. [PMID]

Rosario-Campos, M. C., Miguel, E. C., Quatrano, S., Chacon, P., Ferrao, Y., & Findley, D., et al. (2006). The Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DY-BOCS): An instrument for assessing obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions. Molecular Psychiatry, 11(5), 495-504. [PMID]

Sackeim, H. A., Prudic, J., Devanand, D. P., Nobler, M. S., Lisanby, S. H., & Peyser, S., et al. (2000). A prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of bilateral and right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy at different stimulus intensities. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(5), 425-434. [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.425] [PMID]

Sackeim, H. A., Prudic, J., Fuller, R., Keilp, J., Lavori, P. W., & Olfson, M. (2007). The cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy in community settings. Neuropsychopharmacology, 32(1), 244-254. [DOI:10.1038/sj.npp.1301180] [PMID]

Semkovska, M., & McLoughlin, D. M. (2013). Measuring retrograde autobiographical amnesia following electroconvulsive therapy: Historical perspective and current issues. The Journal of ECT, 29(2), 127-133. [PMID]

Esfahani, S., Motaghipour, Y., Kamkari, K., Zahiredin, A., & Janbozorgi, M. (2012). [Reliability and validity of the Persian version of the yale-brown obsessive-compulsive scale (Y-BOCS). (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology, 17(4), 297-303. [Link]

Sheehan, J. P., Patterson, G., Schlesinger, D., & Xu, Z. (2013). Gamma knife surgery anterior capsulotomy for severe and refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Neurosurgery, 119(5), 1112-1118. [PMID]

Sheth, S. A., Neal, J., Tangherlini, F., Mian, M. K., Gentil, A., & Cosgrove, G. R., et al. (2013). Limbic system surgery for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: A prospective long-term follow-up of 64 patients. Journal of Neurosurgery, 118(3), 491-497. [PMID]

Simpson, H. B. (2009). Pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 2, 527–543. [PMID]

Simpson, H. B., Foa, E. B., Liebowitz, M. R., Huppert, J. D., Cahill, S., & Maher, M. J., et al. (2013). Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs risperidone for augmenting serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(11), 1190-1199. [PMID] [PMCID]

Singh, A., & Kar, S. K. (2017). How electroconvulsive therapy works?: Understanding the neurobiological mechanisms. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 15(3), 210–221. [PMID]

Sundsted, K. K., Burton, M. C., Shah, R., & Lapid, M. I. (2014).Preanesthesia medical evaluation for electroconvulsive therapy: A review of the literature. The Journal of ECT, 30(1), 35-42. [PMID]

Talaei, A., Mortezania, M., Jafarzadeh, F. S., Saghebi, A., & Rezaei, A. A. (2009). Dramatic response of resistant obsessive compulsive disorder to repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation on right supplementary motor area (Case Report). Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences,34(4), 295-298. [Link]

Tomruk, N. B., Saatcioglu, O., Ugurlu, E., & Hacioglu, M. (2010). ECT use in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Klinik Psikofarmakoloji Bülteni-Bulletin of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20(2), 167-170. [DOI:10.1080/10177833.2010.11790653]

Stern, T. A., Fava, M., Wilens, T. E., & Rosenbaum, J. F. (2015). Massachusetts general hospital psychopharmacology and neurotherapeutics. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences. [Link]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Clinical Neuroscience

Received: 2021/06/30 | Accepted: 2021/11/6 | Published: 2023/01/1

Received: 2021/06/30 | Accepted: 2021/11/6 | Published: 2023/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |