Volume 15, Issue 4 (July & August 2024)

BCN 2024, 15(4): 477-488 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Agrawal M, Rajaram S, Kumar G. Internet Addiction and Psychological Health in Adolescent Indian Medical Students: A Cross-sectional Study. BCN 2024; 15 (4) :477-488

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2127-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-2127-en.html

1- Department of Physiology, Government Medical College, Haldwani, India.

2- Department of Physiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, India.

2- Department of Physiology, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, India.

Keywords: Problematic internet use (PIU), Internet addiction, Social media, Indian medical students, Adolescence

Full-Text [PDF 1358 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

1. Introduction

The internet has become indispensable in modern times, offering multiple benefits, such as information, recreation, and communication. However, excessive internet usage has been associated with many problems in some individuals, affecting their personal, professional, and social lives. This "loss of control" or "inability to regulate internet use" has been termed "internet addiction" at its extreme and has been compared to a phenomenon akin to substance abuse, leading to an inquiry into its mechanism, whether its disadvantages outweigh its advantages and if it can be regulated or curtailed by proper intervention (Brand et al., 2014).

The use of the internet and its after-effects vary significantly in different cultures and populations. Thus, few scientists agree with this term, and the field is still extensively researched worldwide. Though "internet addiction" has not been recognized as a clinical entity yet, internet gaming disorder (IGD) was included in diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM5) as a "condition for further study" in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Interestingly, the term "internet addiction" was proposed as a satirical hoax by a New York-based psychiatrist, Ivan Goldberg, in 1995 (New Yorker, 2015). Later, Young observed a young man who developed severe psychosocial problems due to excessive internet use and detected its close association with pathological gambling, a disorder of impulse control in DSM IV (Young, 1998a). She gave the first scientific description in 1996 and later developed an internet addiction test (IAT). She also suggested that there could be various types of internet addiction: Cyber-sexual addiction, cyber-relationship addiction, net compulsions, information overload, and computer addiction (Young, 2004). Many other single- and multiple-case studies were done later. Griffith considered it a subset of behavior addiction, meeting the 6 core components of addiction: Salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse (Griffiths, 2000). Davis, however, avoided the term internet addiction and preferred the term "pathological internet use," referring to "addiction" as a dependency on psychoactive substances (Davis, 2001). Caplan suggested replacing the term "pathological internet use" with "problematic internet use" (PIU) after testing Davis' cognitive-behavioral model of PIU. He suggested that social isolation plays a more significant role in behavioral symptoms of PIU than does the presence of psychopathology (Caplan, 2007).

The terminology is still under debate as to whether it is a relatively less severe maladaptive coping mechanism akin to obsessive-compulsive disorder or impulse control disorder rather than addiction per se (Shapira et al., 2000). People with addiction generally use the internet excessively, ranging anywhere between 40 to 80 hours per week with individual sessions that could last up to 20 hours; however, timing is not considered a hallmark of internet addiction (Young, 2004). Instead, the loss of control is more crucial in assessing this disorder, as seen in various questionnaires. This phenomenon is being studied globally, and assessment tools and cut-off scores are yet to be standardized (Brand et al., 2014).

There has been a lot of speculation to assess if the "addiction" is real. The most important criterion to ascertain "addiction" is "unsuccessful attempts to control the behavior" or "loss of control" (Brand et al., 2014). Using imaging techniques, it has been found recently that prolonged internet use may result in grey matter atrophy, causing a decrease in concentration, memory, and executive ability (Brand et al., 2014). This phenomenon is very similar to other substance abuse and is associated with abnormalities in the dopaminergic system (Hou et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2011) and increased sympathetic nervous activity (Lin et al., 2014), which are related to one another. Increased sympathetic activity is linked to an increase in adrenaline and cortisol levels, which decreases immune function, especially in people with high levels of reported stress (McClelland & Jemmott, 1980; Reed et al., 2015) and psychological morbidity (Agrawal et al., 2021; Brand et al., 2014). Poorer school and work performance (Derbyshire et al., 2013), problems with interpersonal relationships (Kerkhof et al., 2011), neurological impairments (Kim et al., 2011; Kühn & Gallinat, 2014), physical health issues, such as obesity due to lack of physical activity as well as sleep disorders (Vandelanotte et al., 2009) like insomnia, poor sleep duration, latency, and quality have also been documented (Li et al., 2015).

The objectives of this study were to explore the severity of PIU in Indian medical students in their adolescence, to assess its relationship with psychological health/loneliness, and to correlate PIU with the purpose of use.

Although internet abuse is a crucial issue globally, very few studies have explored the situation in India. Adolescents are a particularly vulnerable group owing to their higher experimental and risk-taking behaviors (Young, 1998b), lesser cognitive maturity (Casey et al., 2008), and limited critical thinking ability (Agrawal et al., 2021). Adolescents struggle with issues of self-identity and social adjustment. This study was done on an academic group of Indian medical students in their late adolescence to assess how the purpose of their use impacts their psychosocial health.

2. Materials and Methods

Study subjects

A total of 185 (105 males, 80 females) healthy first-year MBBS (bachelor of medicine, bachelor of surgery) students of Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute (BMCRI) of age group 17-19 years were included in the study (mean age:18.07 years). The exclusion criteria consisted of any previous history of anxiety/depression/psychiatric problems, drug history of antidepressants/tranquilizers, etc. thyroid disorders, or history of substance abuse.

Study instruments

Young’s IAT (YIAT20)

The IAT was used to determine the severity of the internet addiction. The test contains 20 self-reported items, each rated on a scale from 1 to 5, where a score of 1 is defined as "rarely" and 5 as "always." It includes questions on how internet behavior affects the daily lives, social intercourse, sleeping patterns, and feelings of the individual (Faraci et al., 2013). High scores indicate greater problems associated with internet use. As per a recent meta-analysis (Frangos et al., 2012), the scoring was done as follows: 20-39, average users with complete control; 40-69, internet usage with frequent problems/"possible addicts;" and 70-100, internet usage with significant problems/"addicts." Since the cut-off scores for addiction have not been established, we have considered scores ≥40 as PIU. It is a more acceptable term in the scientific community.

UCLA loneliness questionnaire (version 3)

The revised UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) loneliness scale (version 3) consists of 20 statements designed to assess the degree of loneliness. Participants respond to each question using a 4-point scale ("never" to "often"), and each item is scored from 1 to 4, giving the total score from 20 to 80. A higher score indicates a higher severity of loneliness. The measure has high internal consistency (coefficient α=0.89-0.94) and a test re-test correlation over two months of 0.73 (Russell, 1996).

General health questionnaire (GHQ-12)

GHQ-12 is used to detect psychological distress with high sensitivity and specificity. Developed in the 70s, it detects non-psychotic psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, and related psychiatric morbidity. Studies of GHQ-12 have yielded high validity coefficients when administered in several languages and have been used in countries including India. It consists of 12 questions on a Likert scale with best to worst scores (0-3) (Goldberg, 1972; Goldberg et al., 1997).

Self-administered questionnaire

This questionnaire assessed the duration and purpose of internet use in terms of "% of average time spent using the internet daily" in four areas: Social media, gaming, academics, and others (e.g. hobbies, movies, recreation). For example, out of 100% of the time spent using the internet daily, what is the rough proportion of time (in %) they use for social media, academics, others, or gaming? The exact duration in hours could not be assessed accurately as the participants could not quantify the time spent using the internet.

Statistical analysis

The obtained data are represented as Mean±SD. The sample size was calculated based on a recent study on Indian medical students that found internet addiction to be 58.87% (Chaudhari et al., 2015). The formula used was n=Z2 p(1-p)/E2.

Z for α=0.5 is 1.96. The unpaired t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare mean values between the groups. The Pearson correlation was used to find the strength of the association. P<0.05 (two-tailed) were considered significant. This cross-sectional study was done per the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

3. Results

Prevalence of PIU in the study population

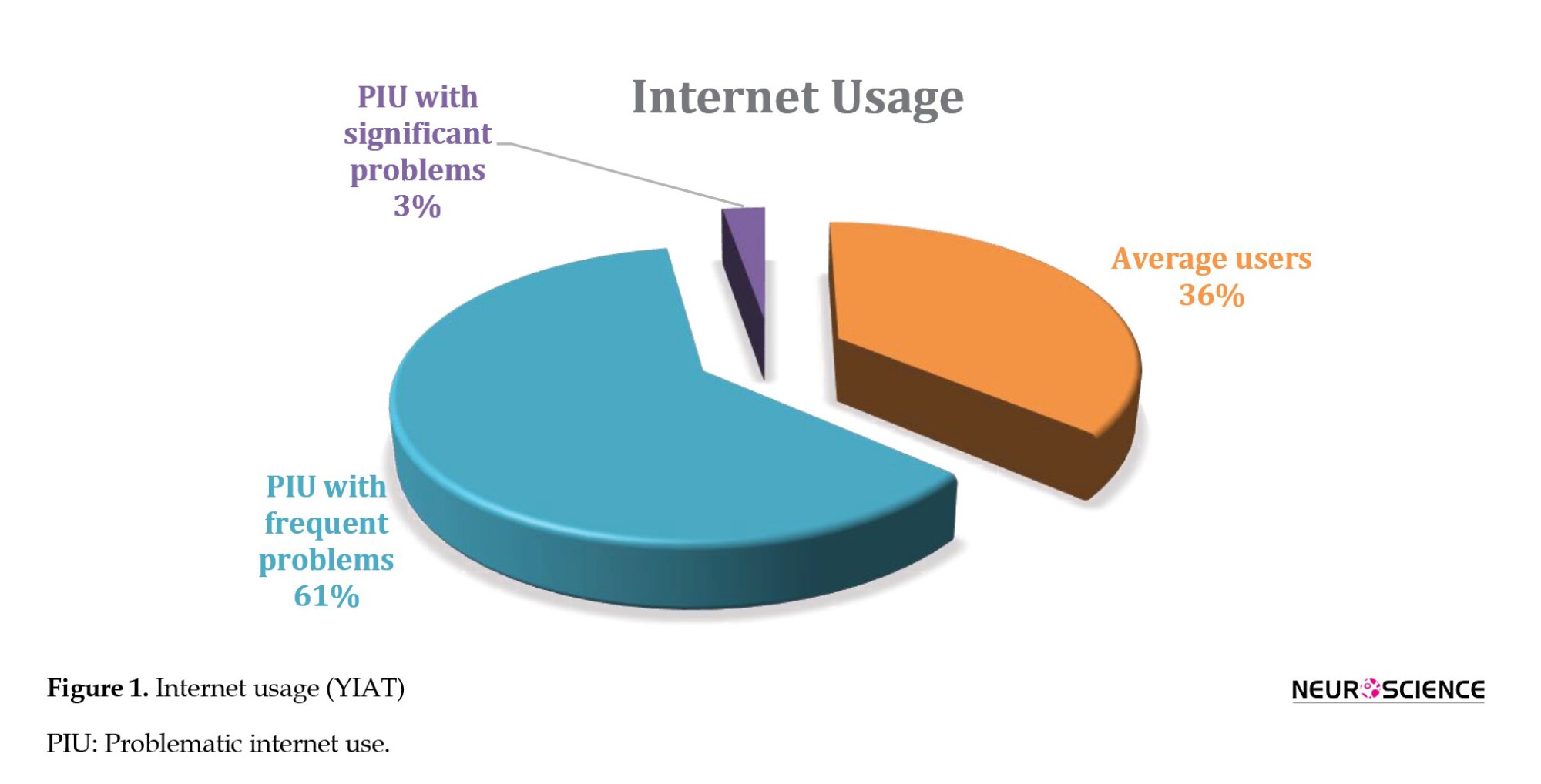

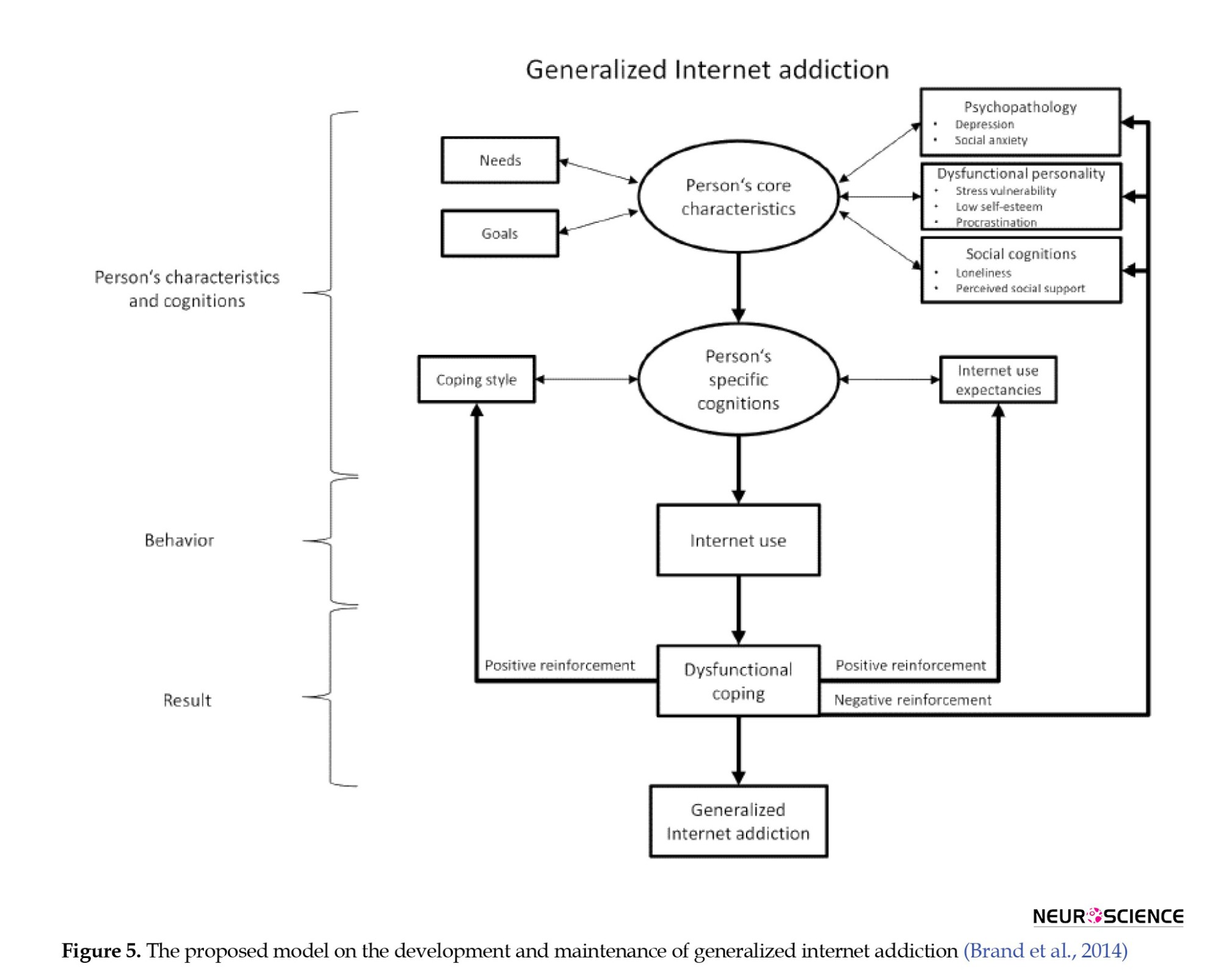

The YIAT was divided into three categories: Average users (20-39), frequent problems/ possible addicts (40-69), and significant problems/ addicts (70-100). Scores above 40 were considered PIU. Out of 185 first-year students, 36% were average users with complete control over internet use, and 64% of medical students showed PIU (61% were possible addicts with frequent problems, 3% were addicts with significant problems) (Figure 1).

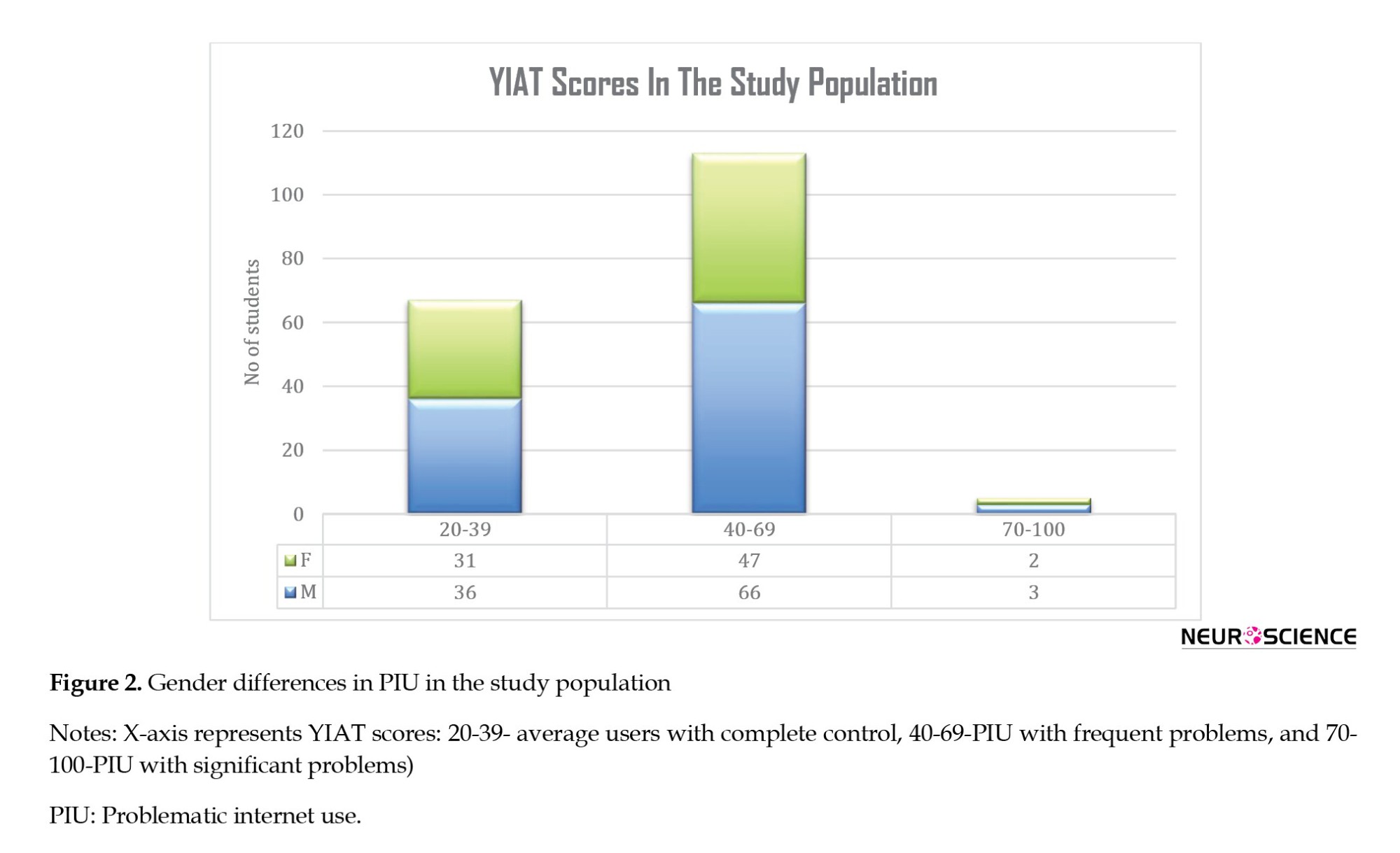

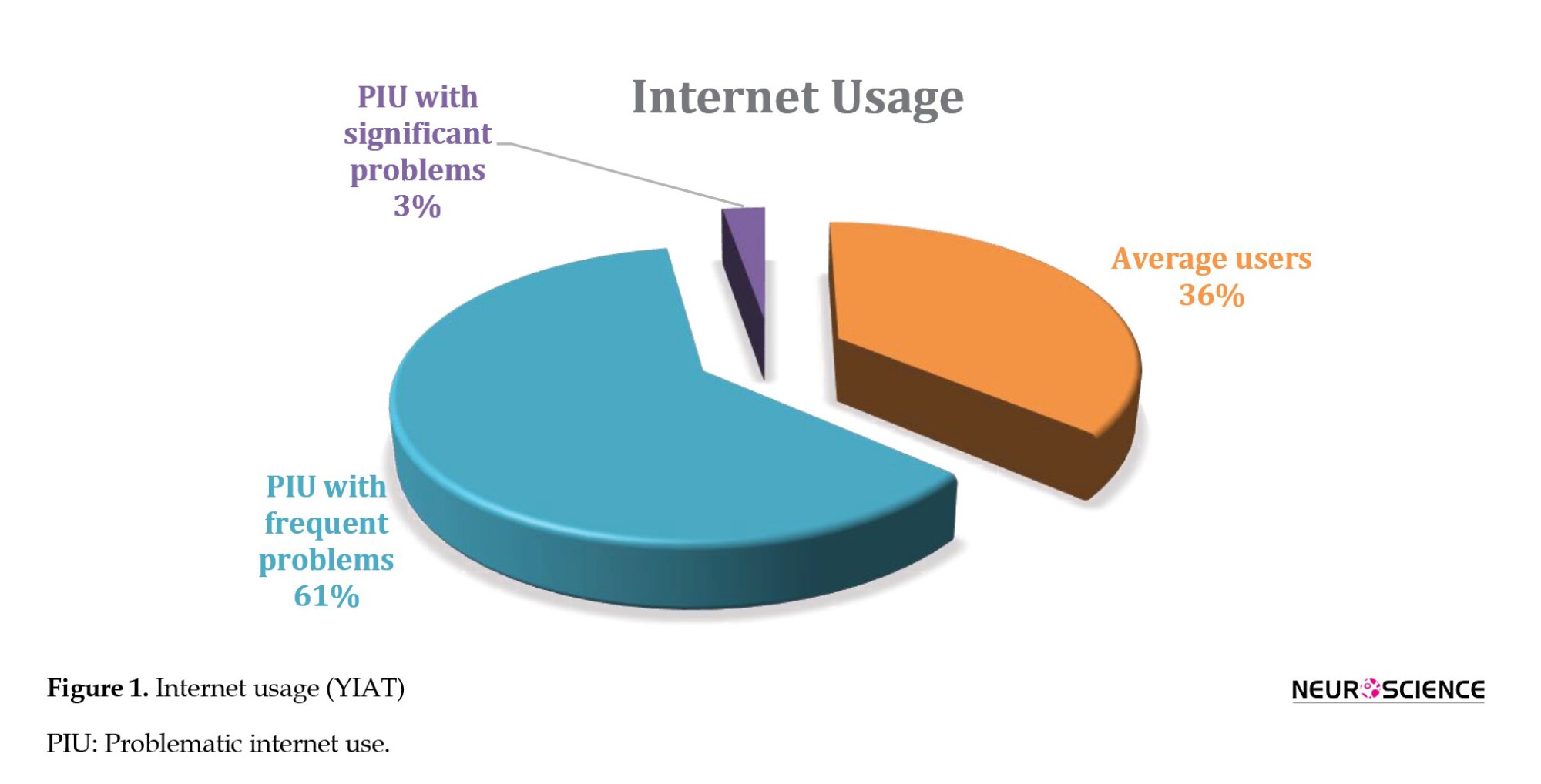

PIU and gender differences

There was a slight preponderance of PIU in males (65.7%) as compared to females (61.25%) (Figure 2)but no significant difference was found between the two genders in internet use (P>0.05) (Figure 2, Table 1).

GHQ and UCLA scores in the study population

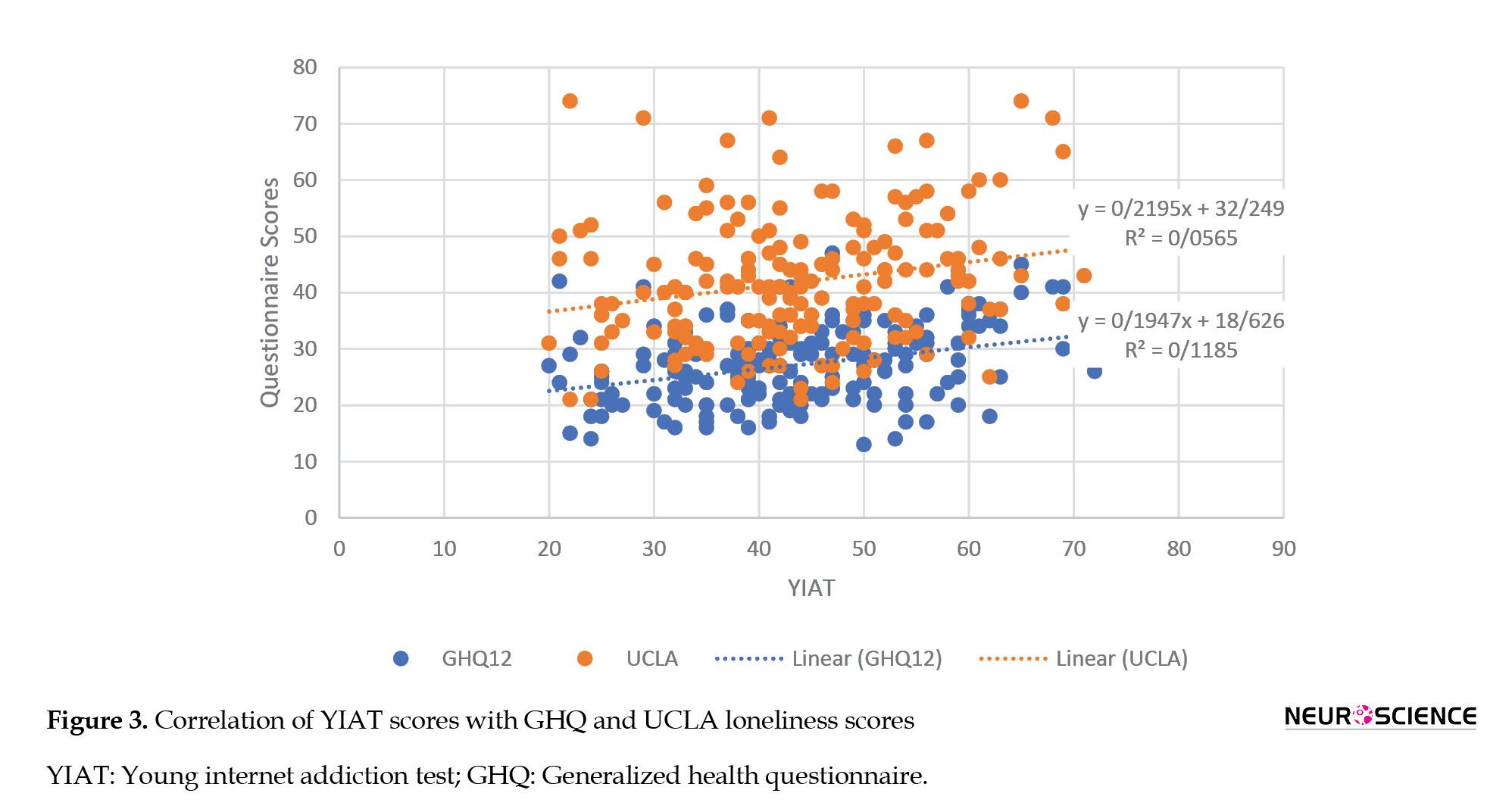

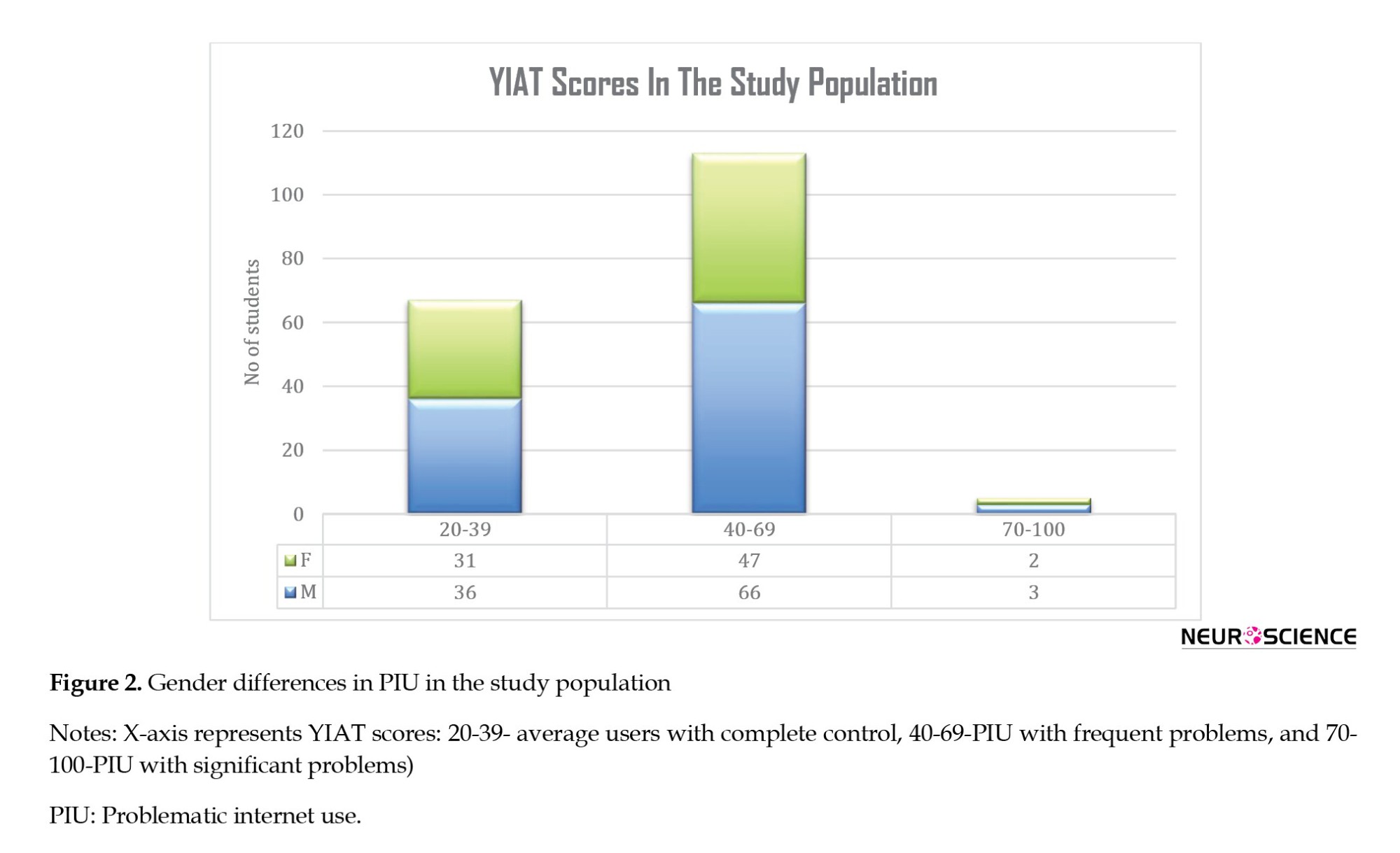

A significant positive correlation was found between DOCS (dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale) scores and GHQ (r=0.34, P<0.01) as well as loneliness (r=0.20, P=0.01) (Figure 3).

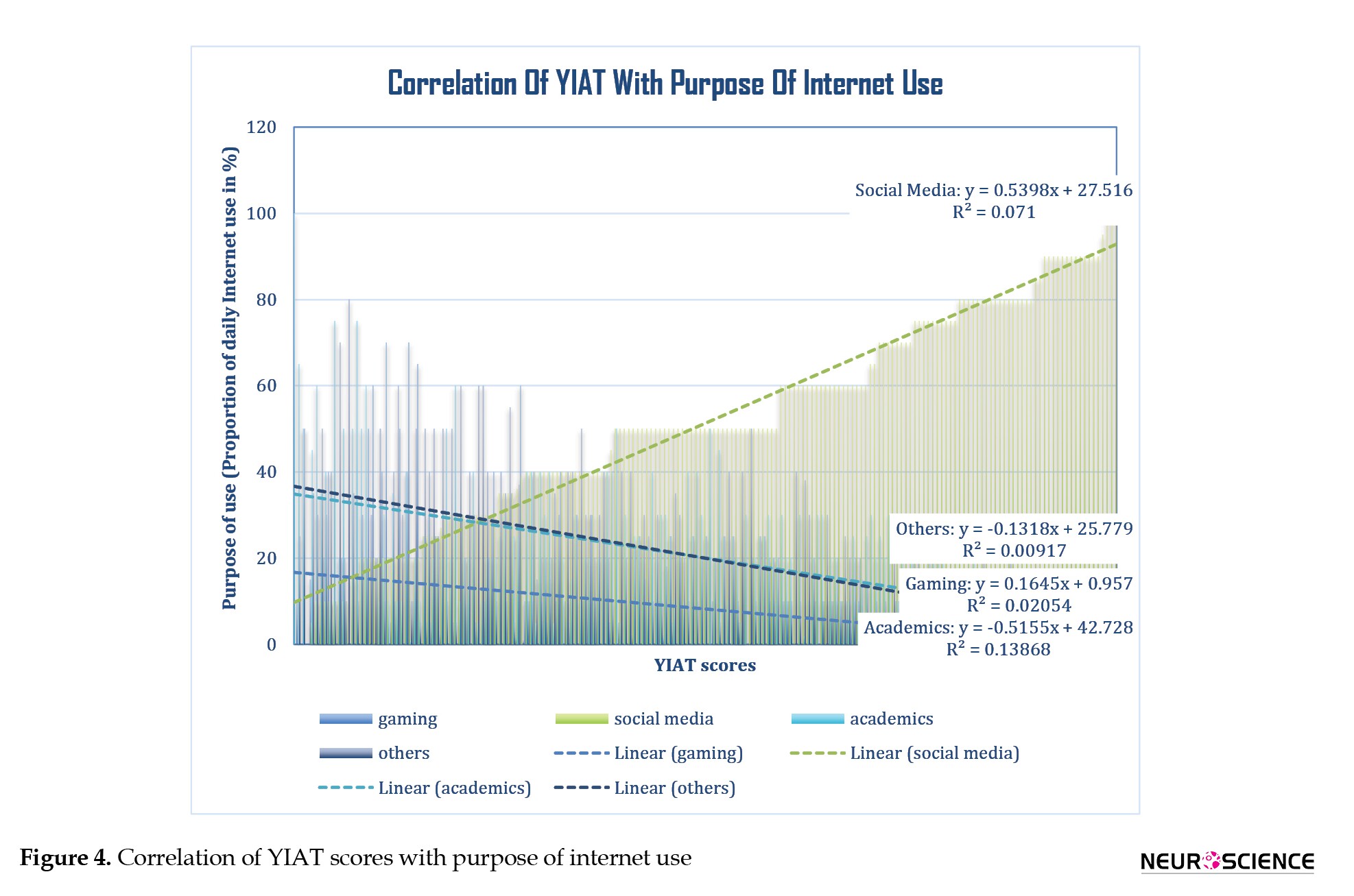

PIU and purpose of use

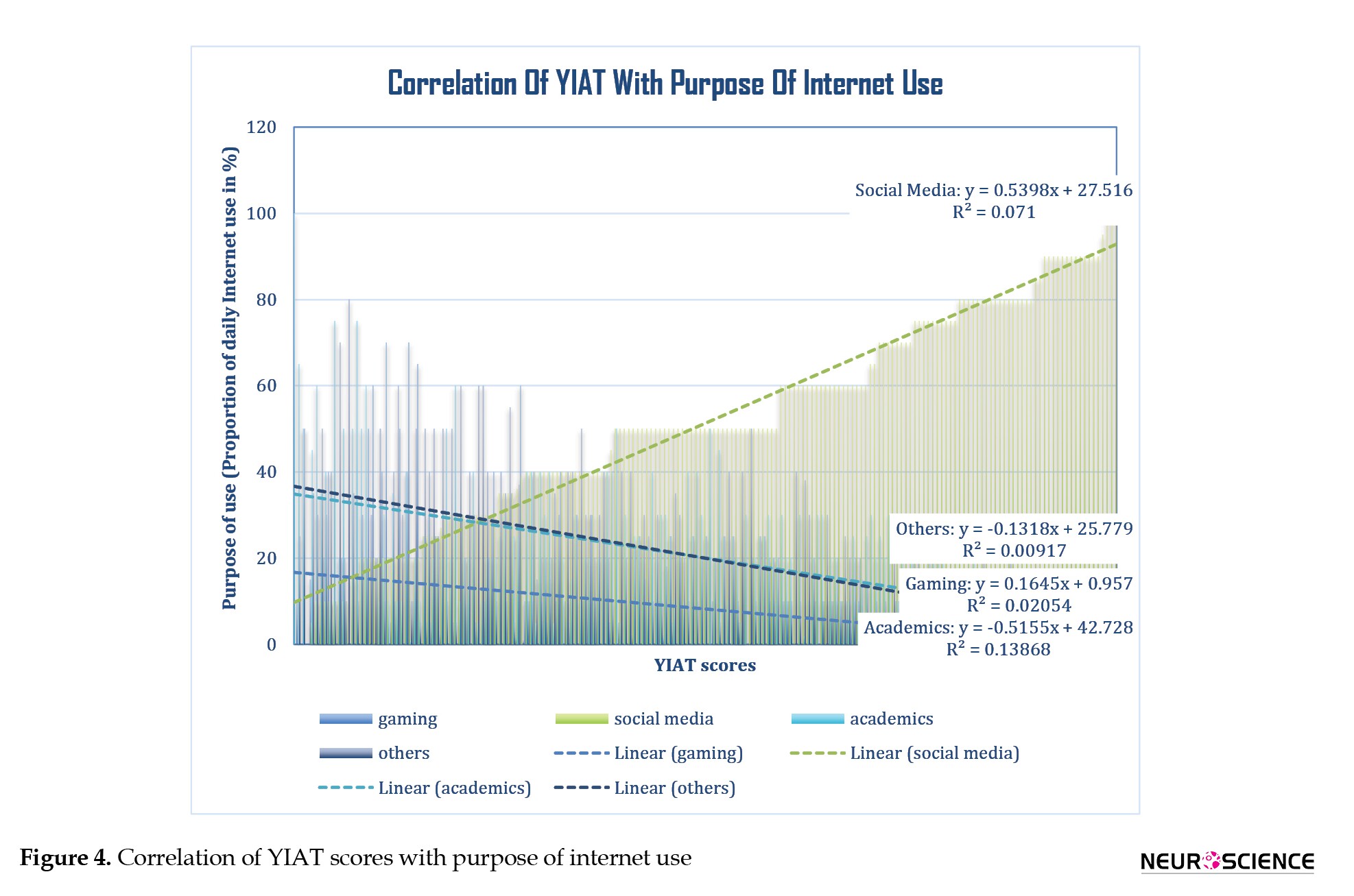

In our population, the maximum average % of total daily time spent using the internet was mostly on social media (51.2%), followed by academics (20%), others (20%), and gaming (8.2%). PIU had a positive correlation with social media (r=0.27, P=0.00) and gaming (r=0.14, P=0.05), whereas a negative correlation with academics (r=-0.37, P<0.0001) and other purposes (r=-0.96, P=0.20) with significant values for social media and academics (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Background characteristics and extent of use

Among 185 medical students, 64% had PIU (61% had frequent problems, and 3% had significant problems). This finding is in agreement with previous studies. In a study, 58.87% of Indian medical students had internet addiction, out of which about 51.42% were mildly addicted while 7.45% were moderately addicted to the internet (Chaudhari et al., 2015). However, due to the heterogeneity of study samples and different diagnostic tools used, there is a marked variation in the prevalence of PIU globally (Brand et al., 2014).

Slight preponderance was found in males (65.7%) compared to females (61.25%). However, no significant difference was found between the two genders. Another study suggests girls are more mature and self-disciplined and pay more attention to information and knowledge provided by the internet compared to boys of the same age, who take the internet as one of life's necessities. Regarding disposition, boys are likelier to indulge in the adventurous, exciting, novel and challenging things. Some studies have shown that boys are more prone to be addicted to online games, and girls are more prone to be addicted to online relations (Ge et al., 2014).

Association with psychological morbidity

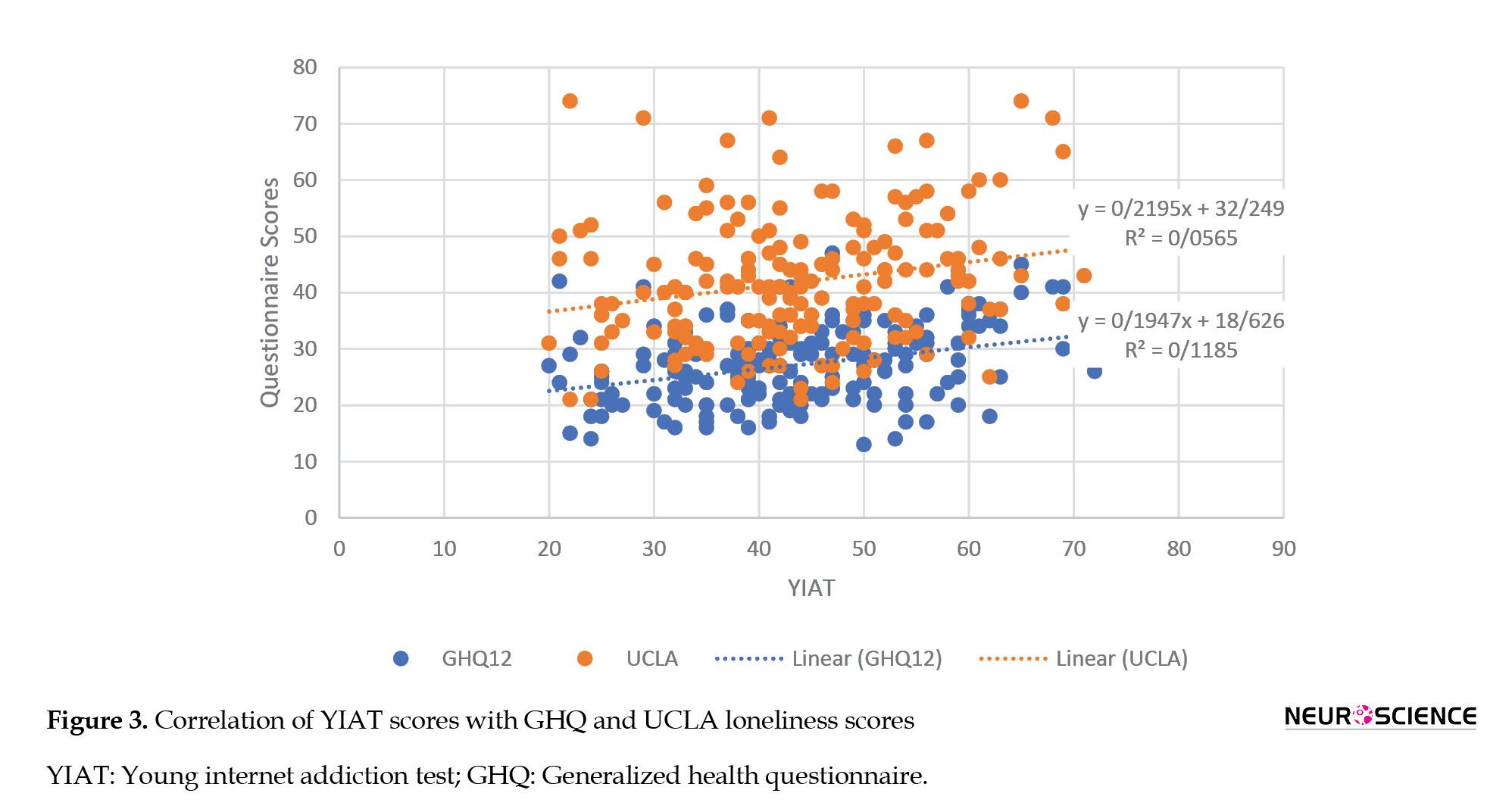

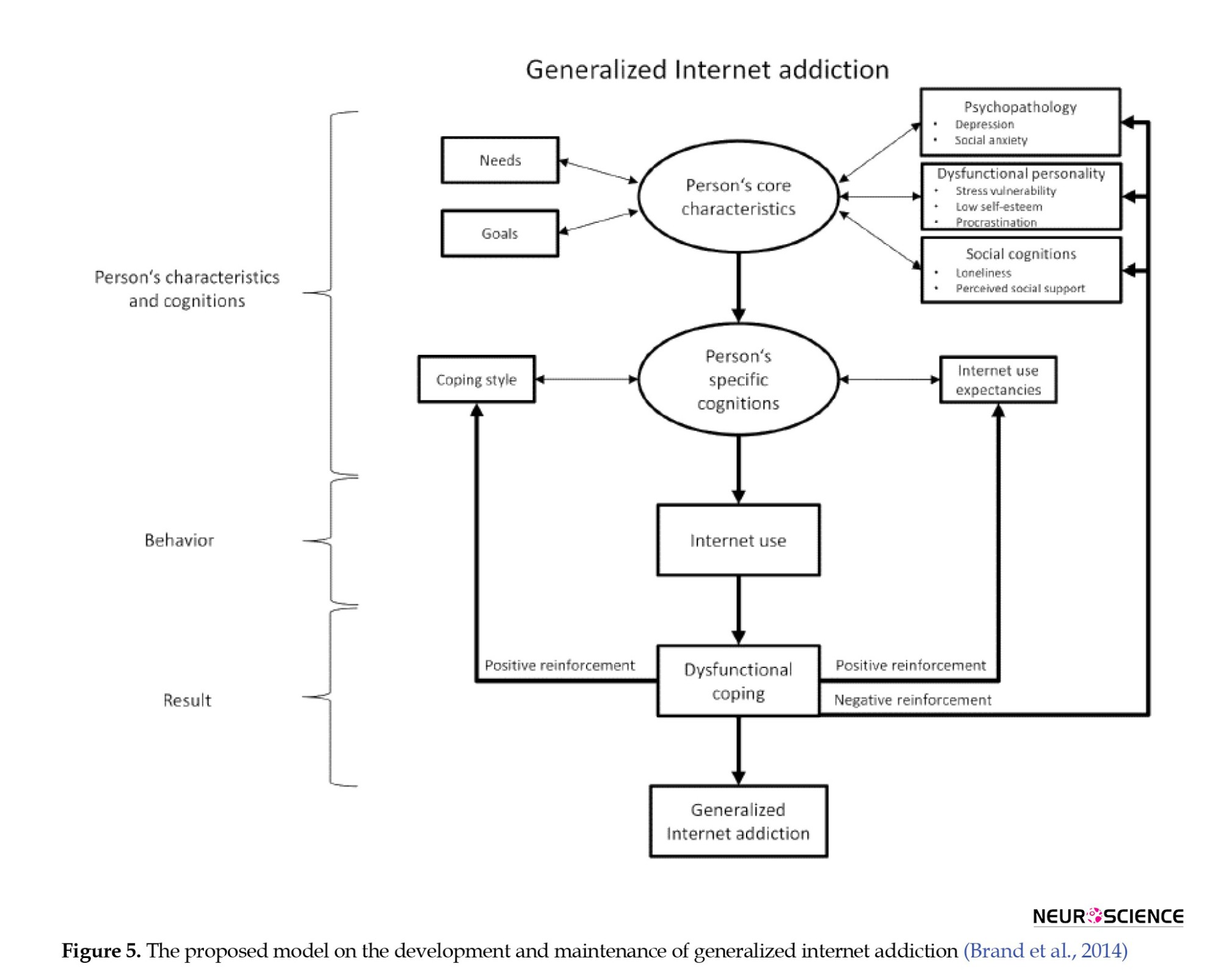

We also found a significant association of PIU with GHQ scores suggestive of psychological morbidity such as anxiety/depression (r=0.34, P<0.0001) and UCLA loneliness scores (r=0.20, P=0.01). Though it is a cross-sectional study and the causal association cannot be determined, there are some theories to explain the association between psychosocial factors and PIU. Lack of social support in real life and feelings of social isolation or loneliness are accounted as the main factors contributing to the development of internet addiction (Davis et al., 2002). Certain psychopathological symptoms have been proposed to cause generalized internet addiction, such as depression and social anxiety (Whang et al., 2003) as well as dysfunctional personality facets like shyness, low self-efficacy, vulnerability due to stress, and tendency to procrastinate (Brand et al., 2014; Caplan, 2007; Chak & Leung, 2004; Ebeling-Witte et al., 2007; Hardie & Tee, 2007; Whang et al., 2003). In addition, specific internet addiction may also be found in individuals with specific predispositions for certain applications (Brand et al., 2014). This condition may then intensify the overuse of the internet as a (dysfunctional) coping strategy to fulfill expectancies from the internet, help distract from problems, escape from reality (positive reinforcement), or reduce negative emotions (negative reinforcement) (Figure 5) (Brand et al., 2014).

Unfortunately, the use of the internet as a coping strategy for negative psychological states may also perpetuate these states in the long term (Li et al., 2015). Eventually, the cognitive control of an individual becomes more difficult due to the strong reinforcing character of specific internet applications, causing a reduction in prefrontal control, leading to decreased grey matter, executive, and decision-making ability (Brand et al., 2014; Thatcher et al., 2008). The most consistent findings from the imaging studies available are atrophy in the prefrontal cortex (i.e. orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), striatum, and insula (Lin & Lei, 2015). Diffusion tensor imaging abnormalities also demonstrated decreased connectivity between the striatum and the inferior frontal gyrus, a connection known to be involved in inhibitory control (Chambers et al., 2009; Swick et al., 2011). This condition might eventually lead to an inability of the prefrontal cortex to regulate the limbic system and may contribute to the persistence of online activity despite personal distress, symptoms of psychological dependence, and diverse negative consequences, thereby exhibiting more impulsivity (i.e. deficits in response inhibition) in certain individuals (Cao et al., 2007; Dalbudak et al., 2013). Individuals with internet addiction are known to have difficulties with response inhibition, which likely contributes to their propensity to relapse in the presence of internet-related cues. Therefore, poor inhibitory control, a decreased ability to suppress automatic and habitual behaviors (Lin et al., 2015) and the role of 'reward pathways' could explain why it is so difficult for some individuals to control their internet use and why they experience "craving" for internet akin to substance abuse (Brand et al., 2014).

Correlation with the purpose of use

In our study population, we found out that the daily use of the internet was maximum for social media (51.2%), followed by academics (20%), other purposes (20%), and gaming (8.2%). There was a significant positive correlation between PIU with social media and a negative correlation with academics. This finding could suggest that certain applications could have a relatively higher addictive potential compared to others.

Social media seems to be a priority for our study population. Research suggests that some young people may be more willing to disclose information on a social network site (SNS) than others (Christofides et al., 2009). While SNS use may result in unhealthy online interactions for some (O’Keeffe et al., 2011), it may provide needed opportunities for many vulnerable youngsters (Burke, 2018) with potential mental health benefits, including socialization, facilitation of supportive relationships, belongingness, self-esteem, identity formation, communication, and learning (O’Keeffe et al., 2011). Some identified risks include cyberbullying, harassment, sexting, and privacy concerns (O’Keeffe et al., 2011; Rice et al., 2014). Decreases in depression have been documented by longitudinal research (Bessière et al., 2010) and re-establishing friendships following social withdrawal (Veretilo & Billick, 2012). However, SNS-induced depression has also been reported with greater depressive symptomology and negative affect (Feinstein et al., 2013; Takahashi et al., 2009). The intervention content, safety, and type of interaction may mediate this bidirectional effect of SNS on depression. For example, positive online interactions may increase social support and reduce depression, and negative online interactions (or with a negative focus) may increase depression and perceived burden (Ge et al., 2014). Qualitative differences among young people may also play a role; for example, those higher in hopelessness (a key predictor of suicidal ideation) may be more likely to engage in blogging-type sites, e.g. online support groups (OSGs) versus sites focused on briefer posts and content, which may in turn help alleviate depression (Dunlop et al., 2011; Griffiths et al., 2012).

One of the longitudinal studies done on female college students to assess media use and academics concluded that cell phone use and social networking distract from concentration on academics. These social media might reflect personality differences (Wilson et al., 2010) or the prioritization of social activities over academics (Davis et al., 2002). It has been suggested that the major predictive variable of internet addiction lies in its function of releasing. The informative function is not a factor in the increase in internet addiction degree. This issue may explain the significant decrease in internet use for academic purposes and our study's positive correlation with social media.

Other internet uses may include online shopping, watching movies and videos, pursuing hobbies, reading news, and pornography. Results of a study indicate that increased email and chat room/instant messaging hours are associated with decreased depressive symptoms, while increased internet hours for shopping, playing games, or research are associated with increased depressive symptoms (Morgan & Cotten, 2003). Literature suggests that an overlap between various addictions is quite common (Sussman et al., 2011), and addictive behaviors co-occur. Problematic computer (game) use could coexist with pornography (Voss et al., 2015), substance use (Grüsser et al., 2005), or gambling (VAN Rooij et al., 2014; Wood et al., 2007). Patients are less likely to be forthcoming about pornography use due to the sensitive and personal nature of the subject.

In our study population, gaming was the least important preoccupation where the internet was considered. This finding contrasts with Chinese people, where gaming is a primary subtype of internet addiction (Li et al., 2015). The appendix of the DSM-5 also includes IGD as a "condition for further study" (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). There is evidence that computer game practice improves the spatial performance and iconic (image representation) and visual attention skills of adolescents (Subrahmanyam et al., 2000) and may be associated with decreased depressive mood and improved self-esteem (VAN Rooij et al., 2014). However, when indulged excessively, gaming may decrease psychosocial functioning and lower grades (VAN Rooij et al., 2014). It is proposed that pleasure, excitement, social interactivity, increased immersion, and seemingly endless achievements associated with certain activities like gaming cause neuropsychological stimulation (Yee, 2006) of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and endogenous dopaminergic reward pathways resulting in increased heart rate, blood pressure, and sympathetic tone (Chaput et al., 2011) as seen by functional magnetic resonance imaging fMRI scans (Ko et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2012). For instance, built-in music adds to the immersive environment of the video game, stimulating the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal stress response and release of cortisol (Hébert et al., 2005). Playing the game competitively with other human players results in higher levels of testosterone in men (Voss et al., 2015; Zilioli & Watson, 2012) and an increased food intake, regardless of appetite sensations (Chaput et al., 2011). It is `a kind of operant conditioning where the individual feels rewarded and is more likely to engage in that behavior again, causing a pattern similar to substance abuse (Brand et al., 2014). Moreover, it provides an escape from rigid parenting structure, in addition to the satisfaction players feel when they advance levels or complete tasks.

Internet usage may have cultural differences and may reflect a society's needs, preferences, and priorities. Also, certain applications of the internet, such as social media interaction and gaming could be more addictive than others, thus highlighting the importance of self-regulation.

Technology is a double-edged sword. It is how we use it that makes all the difference. Excessive time spent on web-based activities, neglect of activities such as sleeping, physical exercise, social interaction, and symptoms of withdrawal when those activities cannot be accessed are the reasons why internet use affects mental health (Block, 2008; Petry et al., 2014). Thus, internet use is not intrinsically harmful but depends on the activity one engages in and how it affects the individual. So, it seems possible that the internet has some benefits when used to a certain extent, but negative consequences might overshadow these properties when used excessively. Therefore, interventions to reduce internet use negative mental health effects could target the negative consequences instead of the internet use itself (Hökby et al., 2016). "Integrated internet addiction prevention program" could help individuals self-regulate excessive internet use (Mun & Lee, 2015). Since the internet has become indispensable in everyday life, future efforts must be made towards developing protocols to integrate the beneficial effects of the internet within a safe and supportive framework and provide positive alternatives to internet usage (Rice et al., 2014).

There are some limitations of this study. First, the causal association could not be assessed since it is a cross-sectional study. Second, accurate information about the duration of internet usage could not be collected and correlated with the severity and purpose of PIU.

5. Conclusion

Based on our study, the severity of PIU had a significant positive correlation with poorer psychological health and loneliness, internet use for social media, and a decrease in academic use. There could be cultural preferences in internet usage, and specific applications may be more addictive than others. This outcome may depend upon personality, needs, and psychosocial factors. Thus, efforts must be made so that internet use is regulated and used judiciously, especially in adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All participants gave informed consent. The study design was cross-sectional and descriptive. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute (BMCRI), Bengaluru, India.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, data collection and writing the original draft: Megha Agrawal; Methodology and data analysis: Megha Agrawal, and Sowmya Rajaram; Review and editing: Sowmya Rajaram, Girija Kumar; Supervision: Sowmya Rajaram, and Girija Kumar.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all participants and Vishwanatha Neela, Statistician, Department of Community Medicine, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, for the help on statistics calculations.

References

The internet has become indispensable in modern times, offering multiple benefits, such as information, recreation, and communication. However, excessive internet usage has been associated with many problems in some individuals, affecting their personal, professional, and social lives. This "loss of control" or "inability to regulate internet use" has been termed "internet addiction" at its extreme and has been compared to a phenomenon akin to substance abuse, leading to an inquiry into its mechanism, whether its disadvantages outweigh its advantages and if it can be regulated or curtailed by proper intervention (Brand et al., 2014).

The use of the internet and its after-effects vary significantly in different cultures and populations. Thus, few scientists agree with this term, and the field is still extensively researched worldwide. Though "internet addiction" has not been recognized as a clinical entity yet, internet gaming disorder (IGD) was included in diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM5) as a "condition for further study" in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Interestingly, the term "internet addiction" was proposed as a satirical hoax by a New York-based psychiatrist, Ivan Goldberg, in 1995 (New Yorker, 2015). Later, Young observed a young man who developed severe psychosocial problems due to excessive internet use and detected its close association with pathological gambling, a disorder of impulse control in DSM IV (Young, 1998a). She gave the first scientific description in 1996 and later developed an internet addiction test (IAT). She also suggested that there could be various types of internet addiction: Cyber-sexual addiction, cyber-relationship addiction, net compulsions, information overload, and computer addiction (Young, 2004). Many other single- and multiple-case studies were done later. Griffith considered it a subset of behavior addiction, meeting the 6 core components of addiction: Salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse (Griffiths, 2000). Davis, however, avoided the term internet addiction and preferred the term "pathological internet use," referring to "addiction" as a dependency on psychoactive substances (Davis, 2001). Caplan suggested replacing the term "pathological internet use" with "problematic internet use" (PIU) after testing Davis' cognitive-behavioral model of PIU. He suggested that social isolation plays a more significant role in behavioral symptoms of PIU than does the presence of psychopathology (Caplan, 2007).

The terminology is still under debate as to whether it is a relatively less severe maladaptive coping mechanism akin to obsessive-compulsive disorder or impulse control disorder rather than addiction per se (Shapira et al., 2000). People with addiction generally use the internet excessively, ranging anywhere between 40 to 80 hours per week with individual sessions that could last up to 20 hours; however, timing is not considered a hallmark of internet addiction (Young, 2004). Instead, the loss of control is more crucial in assessing this disorder, as seen in various questionnaires. This phenomenon is being studied globally, and assessment tools and cut-off scores are yet to be standardized (Brand et al., 2014).

There has been a lot of speculation to assess if the "addiction" is real. The most important criterion to ascertain "addiction" is "unsuccessful attempts to control the behavior" or "loss of control" (Brand et al., 2014). Using imaging techniques, it has been found recently that prolonged internet use may result in grey matter atrophy, causing a decrease in concentration, memory, and executive ability (Brand et al., 2014). This phenomenon is very similar to other substance abuse and is associated with abnormalities in the dopaminergic system (Hou et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2011) and increased sympathetic nervous activity (Lin et al., 2014), which are related to one another. Increased sympathetic activity is linked to an increase in adrenaline and cortisol levels, which decreases immune function, especially in people with high levels of reported stress (McClelland & Jemmott, 1980; Reed et al., 2015) and psychological morbidity (Agrawal et al., 2021; Brand et al., 2014). Poorer school and work performance (Derbyshire et al., 2013), problems with interpersonal relationships (Kerkhof et al., 2011), neurological impairments (Kim et al., 2011; Kühn & Gallinat, 2014), physical health issues, such as obesity due to lack of physical activity as well as sleep disorders (Vandelanotte et al., 2009) like insomnia, poor sleep duration, latency, and quality have also been documented (Li et al., 2015).

The objectives of this study were to explore the severity of PIU in Indian medical students in their adolescence, to assess its relationship with psychological health/loneliness, and to correlate PIU with the purpose of use.

Although internet abuse is a crucial issue globally, very few studies have explored the situation in India. Adolescents are a particularly vulnerable group owing to their higher experimental and risk-taking behaviors (Young, 1998b), lesser cognitive maturity (Casey et al., 2008), and limited critical thinking ability (Agrawal et al., 2021). Adolescents struggle with issues of self-identity and social adjustment. This study was done on an academic group of Indian medical students in their late adolescence to assess how the purpose of their use impacts their psychosocial health.

2. Materials and Methods

Study subjects

A total of 185 (105 males, 80 females) healthy first-year MBBS (bachelor of medicine, bachelor of surgery) students of Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute (BMCRI) of age group 17-19 years were included in the study (mean age:18.07 years). The exclusion criteria consisted of any previous history of anxiety/depression/psychiatric problems, drug history of antidepressants/tranquilizers, etc. thyroid disorders, or history of substance abuse.

Study instruments

Young’s IAT (YIAT20)

The IAT was used to determine the severity of the internet addiction. The test contains 20 self-reported items, each rated on a scale from 1 to 5, where a score of 1 is defined as "rarely" and 5 as "always." It includes questions on how internet behavior affects the daily lives, social intercourse, sleeping patterns, and feelings of the individual (Faraci et al., 2013). High scores indicate greater problems associated with internet use. As per a recent meta-analysis (Frangos et al., 2012), the scoring was done as follows: 20-39, average users with complete control; 40-69, internet usage with frequent problems/"possible addicts;" and 70-100, internet usage with significant problems/"addicts." Since the cut-off scores for addiction have not been established, we have considered scores ≥40 as PIU. It is a more acceptable term in the scientific community.

UCLA loneliness questionnaire (version 3)

The revised UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) loneliness scale (version 3) consists of 20 statements designed to assess the degree of loneliness. Participants respond to each question using a 4-point scale ("never" to "often"), and each item is scored from 1 to 4, giving the total score from 20 to 80. A higher score indicates a higher severity of loneliness. The measure has high internal consistency (coefficient α=0.89-0.94) and a test re-test correlation over two months of 0.73 (Russell, 1996).

General health questionnaire (GHQ-12)

GHQ-12 is used to detect psychological distress with high sensitivity and specificity. Developed in the 70s, it detects non-psychotic psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety, and related psychiatric morbidity. Studies of GHQ-12 have yielded high validity coefficients when administered in several languages and have been used in countries including India. It consists of 12 questions on a Likert scale with best to worst scores (0-3) (Goldberg, 1972; Goldberg et al., 1997).

Self-administered questionnaire

This questionnaire assessed the duration and purpose of internet use in terms of "% of average time spent using the internet daily" in four areas: Social media, gaming, academics, and others (e.g. hobbies, movies, recreation). For example, out of 100% of the time spent using the internet daily, what is the rough proportion of time (in %) they use for social media, academics, others, or gaming? The exact duration in hours could not be assessed accurately as the participants could not quantify the time spent using the internet.

Statistical analysis

The obtained data are represented as Mean±SD. The sample size was calculated based on a recent study on Indian medical students that found internet addiction to be 58.87% (Chaudhari et al., 2015). The formula used was n=Z2 p(1-p)/E2.

Z for α=0.5 is 1.96. The unpaired t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare mean values between the groups. The Pearson correlation was used to find the strength of the association. P<0.05 (two-tailed) were considered significant. This cross-sectional study was done per the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

3. Results

Prevalence of PIU in the study population

The YIAT was divided into three categories: Average users (20-39), frequent problems/ possible addicts (40-69), and significant problems/ addicts (70-100). Scores above 40 were considered PIU. Out of 185 first-year students, 36% were average users with complete control over internet use, and 64% of medical students showed PIU (61% were possible addicts with frequent problems, 3% were addicts with significant problems) (Figure 1).

PIU and gender differences

There was a slight preponderance of PIU in males (65.7%) as compared to females (61.25%) (Figure 2)but no significant difference was found between the two genders in internet use (P>0.05) (Figure 2, Table 1).

GHQ and UCLA scores in the study population

A significant positive correlation was found between DOCS (dimensional obsessive-compulsive scale) scores and GHQ (r=0.34, P<0.01) as well as loneliness (r=0.20, P=0.01) (Figure 3).

PIU and purpose of use

In our population, the maximum average % of total daily time spent using the internet was mostly on social media (51.2%), followed by academics (20%), others (20%), and gaming (8.2%). PIU had a positive correlation with social media (r=0.27, P=0.00) and gaming (r=0.14, P=0.05), whereas a negative correlation with academics (r=-0.37, P<0.0001) and other purposes (r=-0.96, P=0.20) with significant values for social media and academics (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Background characteristics and extent of use

Among 185 medical students, 64% had PIU (61% had frequent problems, and 3% had significant problems). This finding is in agreement with previous studies. In a study, 58.87% of Indian medical students had internet addiction, out of which about 51.42% were mildly addicted while 7.45% were moderately addicted to the internet (Chaudhari et al., 2015). However, due to the heterogeneity of study samples and different diagnostic tools used, there is a marked variation in the prevalence of PIU globally (Brand et al., 2014).

Slight preponderance was found in males (65.7%) compared to females (61.25%). However, no significant difference was found between the two genders. Another study suggests girls are more mature and self-disciplined and pay more attention to information and knowledge provided by the internet compared to boys of the same age, who take the internet as one of life's necessities. Regarding disposition, boys are likelier to indulge in the adventurous, exciting, novel and challenging things. Some studies have shown that boys are more prone to be addicted to online games, and girls are more prone to be addicted to online relations (Ge et al., 2014).

Association with psychological morbidity

We also found a significant association of PIU with GHQ scores suggestive of psychological morbidity such as anxiety/depression (r=0.34, P<0.0001) and UCLA loneliness scores (r=0.20, P=0.01). Though it is a cross-sectional study and the causal association cannot be determined, there are some theories to explain the association between psychosocial factors and PIU. Lack of social support in real life and feelings of social isolation or loneliness are accounted as the main factors contributing to the development of internet addiction (Davis et al., 2002). Certain psychopathological symptoms have been proposed to cause generalized internet addiction, such as depression and social anxiety (Whang et al., 2003) as well as dysfunctional personality facets like shyness, low self-efficacy, vulnerability due to stress, and tendency to procrastinate (Brand et al., 2014; Caplan, 2007; Chak & Leung, 2004; Ebeling-Witte et al., 2007; Hardie & Tee, 2007; Whang et al., 2003). In addition, specific internet addiction may also be found in individuals with specific predispositions for certain applications (Brand et al., 2014). This condition may then intensify the overuse of the internet as a (dysfunctional) coping strategy to fulfill expectancies from the internet, help distract from problems, escape from reality (positive reinforcement), or reduce negative emotions (negative reinforcement) (Figure 5) (Brand et al., 2014).

Unfortunately, the use of the internet as a coping strategy for negative psychological states may also perpetuate these states in the long term (Li et al., 2015). Eventually, the cognitive control of an individual becomes more difficult due to the strong reinforcing character of specific internet applications, causing a reduction in prefrontal control, leading to decreased grey matter, executive, and decision-making ability (Brand et al., 2014; Thatcher et al., 2008). The most consistent findings from the imaging studies available are atrophy in the prefrontal cortex (i.e. orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), striatum, and insula (Lin & Lei, 2015). Diffusion tensor imaging abnormalities also demonstrated decreased connectivity between the striatum and the inferior frontal gyrus, a connection known to be involved in inhibitory control (Chambers et al., 2009; Swick et al., 2011). This condition might eventually lead to an inability of the prefrontal cortex to regulate the limbic system and may contribute to the persistence of online activity despite personal distress, symptoms of psychological dependence, and diverse negative consequences, thereby exhibiting more impulsivity (i.e. deficits in response inhibition) in certain individuals (Cao et al., 2007; Dalbudak et al., 2013). Individuals with internet addiction are known to have difficulties with response inhibition, which likely contributes to their propensity to relapse in the presence of internet-related cues. Therefore, poor inhibitory control, a decreased ability to suppress automatic and habitual behaviors (Lin et al., 2015) and the role of 'reward pathways' could explain why it is so difficult for some individuals to control their internet use and why they experience "craving" for internet akin to substance abuse (Brand et al., 2014).

Correlation with the purpose of use

In our study population, we found out that the daily use of the internet was maximum for social media (51.2%), followed by academics (20%), other purposes (20%), and gaming (8.2%). There was a significant positive correlation between PIU with social media and a negative correlation with academics. This finding could suggest that certain applications could have a relatively higher addictive potential compared to others.

Social media seems to be a priority for our study population. Research suggests that some young people may be more willing to disclose information on a social network site (SNS) than others (Christofides et al., 2009). While SNS use may result in unhealthy online interactions for some (O’Keeffe et al., 2011), it may provide needed opportunities for many vulnerable youngsters (Burke, 2018) with potential mental health benefits, including socialization, facilitation of supportive relationships, belongingness, self-esteem, identity formation, communication, and learning (O’Keeffe et al., 2011). Some identified risks include cyberbullying, harassment, sexting, and privacy concerns (O’Keeffe et al., 2011; Rice et al., 2014). Decreases in depression have been documented by longitudinal research (Bessière et al., 2010) and re-establishing friendships following social withdrawal (Veretilo & Billick, 2012). However, SNS-induced depression has also been reported with greater depressive symptomology and negative affect (Feinstein et al., 2013; Takahashi et al., 2009). The intervention content, safety, and type of interaction may mediate this bidirectional effect of SNS on depression. For example, positive online interactions may increase social support and reduce depression, and negative online interactions (or with a negative focus) may increase depression and perceived burden (Ge et al., 2014). Qualitative differences among young people may also play a role; for example, those higher in hopelessness (a key predictor of suicidal ideation) may be more likely to engage in blogging-type sites, e.g. online support groups (OSGs) versus sites focused on briefer posts and content, which may in turn help alleviate depression (Dunlop et al., 2011; Griffiths et al., 2012).

One of the longitudinal studies done on female college students to assess media use and academics concluded that cell phone use and social networking distract from concentration on academics. These social media might reflect personality differences (Wilson et al., 2010) or the prioritization of social activities over academics (Davis et al., 2002). It has been suggested that the major predictive variable of internet addiction lies in its function of releasing. The informative function is not a factor in the increase in internet addiction degree. This issue may explain the significant decrease in internet use for academic purposes and our study's positive correlation with social media.

Other internet uses may include online shopping, watching movies and videos, pursuing hobbies, reading news, and pornography. Results of a study indicate that increased email and chat room/instant messaging hours are associated with decreased depressive symptoms, while increased internet hours for shopping, playing games, or research are associated with increased depressive symptoms (Morgan & Cotten, 2003). Literature suggests that an overlap between various addictions is quite common (Sussman et al., 2011), and addictive behaviors co-occur. Problematic computer (game) use could coexist with pornography (Voss et al., 2015), substance use (Grüsser et al., 2005), or gambling (VAN Rooij et al., 2014; Wood et al., 2007). Patients are less likely to be forthcoming about pornography use due to the sensitive and personal nature of the subject.

In our study population, gaming was the least important preoccupation where the internet was considered. This finding contrasts with Chinese people, where gaming is a primary subtype of internet addiction (Li et al., 2015). The appendix of the DSM-5 also includes IGD as a "condition for further study" (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). There is evidence that computer game practice improves the spatial performance and iconic (image representation) and visual attention skills of adolescents (Subrahmanyam et al., 2000) and may be associated with decreased depressive mood and improved self-esteem (VAN Rooij et al., 2014). However, when indulged excessively, gaming may decrease psychosocial functioning and lower grades (VAN Rooij et al., 2014). It is proposed that pleasure, excitement, social interactivity, increased immersion, and seemingly endless achievements associated with certain activities like gaming cause neuropsychological stimulation (Yee, 2006) of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and endogenous dopaminergic reward pathways resulting in increased heart rate, blood pressure, and sympathetic tone (Chaput et al., 2011) as seen by functional magnetic resonance imaging fMRI scans (Ko et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2012). For instance, built-in music adds to the immersive environment of the video game, stimulating the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal stress response and release of cortisol (Hébert et al., 2005). Playing the game competitively with other human players results in higher levels of testosterone in men (Voss et al., 2015; Zilioli & Watson, 2012) and an increased food intake, regardless of appetite sensations (Chaput et al., 2011). It is `a kind of operant conditioning where the individual feels rewarded and is more likely to engage in that behavior again, causing a pattern similar to substance abuse (Brand et al., 2014). Moreover, it provides an escape from rigid parenting structure, in addition to the satisfaction players feel when they advance levels or complete tasks.

Internet usage may have cultural differences and may reflect a society's needs, preferences, and priorities. Also, certain applications of the internet, such as social media interaction and gaming could be more addictive than others, thus highlighting the importance of self-regulation.

Technology is a double-edged sword. It is how we use it that makes all the difference. Excessive time spent on web-based activities, neglect of activities such as sleeping, physical exercise, social interaction, and symptoms of withdrawal when those activities cannot be accessed are the reasons why internet use affects mental health (Block, 2008; Petry et al., 2014). Thus, internet use is not intrinsically harmful but depends on the activity one engages in and how it affects the individual. So, it seems possible that the internet has some benefits when used to a certain extent, but negative consequences might overshadow these properties when used excessively. Therefore, interventions to reduce internet use negative mental health effects could target the negative consequences instead of the internet use itself (Hökby et al., 2016). "Integrated internet addiction prevention program" could help individuals self-regulate excessive internet use (Mun & Lee, 2015). Since the internet has become indispensable in everyday life, future efforts must be made towards developing protocols to integrate the beneficial effects of the internet within a safe and supportive framework and provide positive alternatives to internet usage (Rice et al., 2014).

There are some limitations of this study. First, the causal association could not be assessed since it is a cross-sectional study. Second, accurate information about the duration of internet usage could not be collected and correlated with the severity and purpose of PIU.

5. Conclusion

Based on our study, the severity of PIU had a significant positive correlation with poorer psychological health and loneliness, internet use for social media, and a decrease in academic use. There could be cultural preferences in internet usage, and specific applications may be more addictive than others. This outcome may depend upon personality, needs, and psychosocial factors. Thus, efforts must be made so that internet use is regulated and used judiciously, especially in adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All participants gave informed consent. The study design was cross-sectional and descriptive. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute (BMCRI), Bengaluru, India.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, data collection and writing the original draft: Megha Agrawal; Methodology and data analysis: Megha Agrawal, and Sowmya Rajaram; Review and editing: Sowmya Rajaram, Girija Kumar; Supervision: Sowmya Rajaram, and Girija Kumar.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all participants and Vishwanatha Neela, Statistician, Department of Community Medicine, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute, for the help on statistics calculations.

References

Agrawal, M., Rajaram, S., & Girija, B. (2021). Exploring the effects of Internet on cognition and sleep in Indian medical students - A cross-sectional study. National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 11(5), 506-506. [DOI:10.5455/njppp.2021.11.12346202011012021]

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5TM, 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596]

Bessière, K., Pressman, S., Kiesler, S., & Kraut, R. (2010). Effects of internet use on health and depression: A longitudinal study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 12(1), e1149. [DOI:10.2196/jmir.1149]

Block, J. J. (2008). Issues for DSM-V: Internet addiction. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(3), 306-307. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101556]

Brand, M., Young, K. S., & Laier, C. (2014). Prefrontal control and internet addiction: A theoretical model and review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging findings. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 375. [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00375]

Burke, M. (2018). Reading, writing, relationships: The impact of social network sites on relationships and well-being (PhD dissertation). Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University. [DOI: 10.1184/R1/6721256.v1]

Cao, F., Su, L., Liu, T., & Gao, X. (2007). The relationship between impulsivity and Internet addiction in a sample of Chinese adolescents. European Psychiatry: The Journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 22(7), 466-471. [DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.05.004]

Caplan, S. E. (2007). Relations among loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic internet use. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(2), 234-242. [DOI:10.1089/cpb.2006.9963]

Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., & Hare, T. A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1124(1), 111-126. [DOI:10.1196/annals.1440.010]

Chak, K., & Leung, L. (2004). Shyness and locus of control as predictors of internet addiction and internet use. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(5), 559-570. [DOI:10.1089/cpb.2004.7.559]

Chambers, S. M., Fasano, C. A., Papapetrou, E. P., Tomishima, M., Sadelain, M., & Studer, L. (2009). Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nature Biotechnology, 27(3), 275-280. [DOI:10.1038/nbt.1529]

Chaput, J. P., Visby, T., Nyby, S., Klingenberg, L., Gregersen, N. T., & Tremblay, A., et al. (2011). Video game playing increases food intake in adolescents: A randomized crossover study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 93(6), 1196-1203. [DOI:10.3945/ajcn.110.008680]

Chaudhari, B., Menon, P., Saldanha, D., Tewari, A., & Bhattacharya, L. (2015). Internet addiction and its determinants among medical students. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 24(2), 158-162. [DOI:10.4103/0972-6748.181729]

Christofides, E., Muise, A., & Desmarais, S. (2009). Information disclosure and control on Facebook: Are they two sides of the same coin or two different processes? Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 12(3), 341-345. [DOI:10.1089/cpb.2008.0226]

Dalbudak, E., Evren, C., Aldemir, S., Coskun, K. S., Ugurlu, H., & Yildirim, F. G. (2013). Relationship of internet addiction severity with depression, anxiety, and alexithymia, temperament and character in university students. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16(4), 272-278. [DOI:10.1089/cyber.2012.0390]

Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17(2), 187-195. [DOI:10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8]

Davis, R. A., Flett, G. L., & Besser, A. (2002). Validation of a new scale for measuring problematic internet use: Implications for pre-employment screening. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 5(4), 331-345. [DOI:10.1089/109493102760275581]

Derbyshire, K. L., Lust, K. A., Schreiber, L. R. N., Odlaug, B. L., Christenson, G. A., & Golden, D. J., et al. (2013). Problematic Internet use and associated risks in a college sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(5), 415-422. [DOI:10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.11.003]

Dunlop, S. M., More, E., & Romer, D. (2011). Where do youth learn about suicides on the Internet, and what influence does this have on suicidal ideation? The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(10), 1073-1080. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02416.x]

Ebeling-Witte, S., Frank, M. L., & Lester, D. (2007). Shyness, Internet use, and personality. Cyberpsychology & Behavior: The Impact of the Internet, Multimedia and Virtual Reality on Behavior and Society, 10(5), 713-716. [DOI:10.1089/cpb.2007.9964]

Faraci, P., Craparo, G., Messina, R., & Severino, S. (2013). Internet Addiction Test (IAT): Which is the best factorial solution? Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(10), e2935. [DOI:10.2196/jmir.2935]

Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., & Davila, J. (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(3), 161-170. [DOI:10.1037/a0033111]

Frangos, C. C., Frangos, C. C., & Sotiropoulos, I. (2012). A meta-analysis of the reliabilty of young’s internet addiction test. Paper presented at: The World Congress on Engineering 2012. London, 4 - 6 July 2012. [Link]

Ge, Y., Se, J., & Zhang, J. (2014). Research on relationship among internet-addiction, personality traits and mental health of urban left-behind children. Global Journal of Health Science, 7(4), 60-69. [DOI:10.5539/gjhs.v7n4p60]

Goldberg, D. (1972). The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire: A technique for the identification and assessment of non-psychotic psychiatric illness. Maudsley Monograph, 21. [Link]

Goldberg, D. P., Gater, R., Sartorius, N., Ustun, T. B., Piccinelli, M., & Gureje, O., et al. (1997). The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 191-197. [DOI:10.1017/s0033291796004242]

Griffiths, K. M., Mackinnon, A. J., Crisp, D. A., Christensen, H., Bennett, K., & Farrer, L. (2012). The effectiveness of an online support group for members of the community with depression: A randomised controlled trial. Plos One, 7(12), e53244. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0053244]

Griffiths, M. (2000). Does Internet and computer “addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3(2), 211-218. [DOI:10.1089/109493100316067]

Grüsser, S. M., Thalemann, R., Albrecht, U., & Thalemann, C. N. (2005). Excessive computer usage in adolescents-Results of a psychometric evaluation. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 117(5-6), 188-195. [DOI:10.1007/s00508-005-0339-6]

Hardie, E., & Tee, M. (2007). Excessive Internet Use: The role of personality, loneliness and social support networks in internet addiction. Australian Journal of Emerging Technologies and Society, 5(1), 34. [Link]

Hébert, S., Béland, R., Dionne-Fournelle, O., Crête, M., & Lupien, S. J. (2005). Physiological stress response to video-game playing: The contribution of built-in music. Life Sciences, 76(20), 2371-2380. [DOI:10.1016/j.lfs.2004.11.011]

Hökby, S., Hadlaczky, G., Westerlund, J., Wasserman, D., Balazs, J., & Germanavicius, A., et al. (2016). Are mental health effects of internet use attributable to the web-based content or perceived consequences of usage? A longitudinal study of European Adolescents. JMIR Mental Health, 3(3), e31. [DOI:10.2196/mental.5925]

Hou, H., Jia, S., Hu, S., Fan, R., Sun, W., & Sun, T., et al. (2012). Reduced striatal dopamine transporters in people with internet addiction disorder. Journal of Biomedicine & Biotechnology, 2012, 854524. [PMID]

Kerkhof, P., Finkenauer, C., & Muusses, L. D. (2011). Relational consequences of compulsive Internet use: A longitudinal study among newlyweds. Human Communication Research, 37(2), 147-173. [DOI:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01397.x]

Kim, S. H., Baik, S. H., Park, C. S., Kim, S. J., Choi, S. W., & Kim, S. E. (2011). Reduced striatal dopamine D2 receptors in people with Internet addiction. Neuroreport, 22(8), 407-411. [DOI:10.1097/WNR.0b013e328346e16e]

Ko, C. H., Liu, G. C., Yen, J. Y., Chen, C. Y., Yen, C.F., & Chen, C. S. (2013). Brain correlates of craving for online gaming under cue exposure in subjects with Internet gaming addiction and in remitted subjects. Addiction Biology, 18(3), 559-569. [DOI:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00405.x]

Kühn, S., & Gallinat, J. (2014). Brain structure and functional connectivity associated with pornography consumption: The brain on porn. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(7), 827-834. [DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.93]

Li, W., O’Brien, J. E., Snyder, S. M., & Howard, M. O. (2015). Characteristics of internet addiction/pathological internet use in U.S. university students: A qualitative-method investigation. Plos One, 10(2), e0117372. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0117372]

Lin, F., & Lei, H. (2015). Structural brain imaging and internet addiction. In: C. Montag, M. Reuter (Eds.). Internet addiction. Studies in neuroscience, psychology and behavioral economics. Cham: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-07242-5_2]

Lin, F., Zhou, Y., Du, Y., Zhao, Z., Qin, L., & Xu, J., et al. (2015). Aberrant corticostriatal functional circuits in adolescents with Internet addiction disorder. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 356. [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00356]

Lin, P. C., Kuo, S. Y., Lee, P. H., Sheen, T.C., & Chen, S. R. (2014). Effects of internet addiction on heart rate variability in school-aged children. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 29(6), 493-498. [DOI:10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182a477d5]

McClelland, D. C., & Jemmott, J. B. (1980). Power motivation, stress and physical illness. Journal of Human Stress, 6(4), 6-15. [DOI:10.1080/0097840X.1980.9936101]

Morgan, C., & Cotten, S. R. (2003). The relationship between internet activities and depressive symptoms in a sample of college freshmen. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 6(2), 133-142. [DOI:10.1089/109493103321640329]

Mun, S. Y., & Lee, B. S. (2015). [Effects of an Integrated Internet Addiction Prevention Program on Elementary Students’ Self-regulation and Internet Addiction]. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 45(2), 251-261. [DOI:10.4040/jkan.2015.45.2.251]

O’Keeffe, G. S., Clarke-Pearson, K., & Council on Communications and Media. (2011). The impact of social media on children, adolescents, and families. Pediatrics, 127(4), 800-804. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2011-0054]

Petry, N. M., Rehbein, F., Gentile, D. A., Lemmens, J. S., Rumpf, H. J., & Mößle, T., et al. (2014). An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 109(9), 1399-1406. [DOI:10.1111/add.12457]

Reed, P., Vile, R., Osborne, L. A., Romano, M., & Truzoli, R. (2015). Problematic internet usage and immune function. Plos One, 10(8), e0134538. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0134538]

Rice, S. M., Goodall, J., Hetrick, S. E., Parker, A. G., Gilbertson, T., & Amminger, G. P., et al. (2014). Online and social networking interventions for the treatment of depression in young people: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(9), e206. [DOI:10.2196/jmir.3304]

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20-40. [DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2] [PMID]

Shapira, N. A., Goldsmith, T. D., Keck, P. E., Khosla, U. M., & McElroy, S. L. (2000). Psychiatric features of individuals with problematic internet use. Journal of Affective Disorders, 57(1-3), 267-272. [DOI:10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00107-x]

Subrahmanyam, K., Kraut, R. E., Greenfield, P. M., & Gross, E. F. (2000). The impact of home computer use on children’s activities and development. The Future of Children, 10(2), 123-144. [DOI:10.2307/1602692]

Sun, Y., Ying, H., Seetohul, R. M., Xuemei, W., Ya, Z., & Qian, L., et al. (2012). Brain fMRI study of crave induced by cue pictures in online game addicts (male adolescents). Behavioural Brain Research, 233(2), 563-576. [DOI:10.1016/j.bbr.2012.05.005]

Sussman, S., Lisha, N., & Griffiths, M. (2011). Prevalence of the addictions: A problem of the majority or the minority? Evaluation & the Health Professions, 34(1), 3-56. [DOI:10.1177/0163278710380124]

Swick, D., Ashley, V., & Turken, U. (2011). Are the neural correlates of stopping and not going identical? Quantitative meta-analysis of two response inhibition tasks. NeuroImage, 56(3), 1655-1665. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.070]

Takahashi, Y., Uchida, C., Miyaki, K., Sakai, M., Shimbo, T., & Nakayama, T. (2009). Potential benefits and harms of a peer support social network service on the internet for people with depressive tendencies: Qualitative content analysis and social network analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(3), e29. [DOI:10.2196/jmir.1142]

Thatcher, A., Wretschko, G., & Fridjhon, P. (2008). Online flow experiences, problematic Internet use and Internet procrastination. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(5), 2236-2254. [DOI:10.1016/j.chb.2007.10.008]

VAN Rooij, A. J., Kuss, D. J., Griffiths, M. D., Shorter, G. W., Schoenmakers, M. T., & VAN DE Mheen, D. (2014). The (co-)occurrence of problematic video gaming, substance use, and psychosocial problems in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(3), 157-165. [DOI:10.1556/JBA.3.2014.013]

Vandelanotte, C., Sugiyama, T., Gardiner, P., & Owen, N. (2009). Associations of leisure-time internet and computer use with overweight and obesity, physical activity and sedentary behaviors: Cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(3), e28. [DOI:10.2196/jmir.1084]

Veretilo, P., & Billick, S. B. (2012). Psychiatric illness and facebook: A case report. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 83(3), 385-389. [DOI:10.1007/s11126-012-9207-5]

Voss, A., Cash, H., Hurdiss, S., Bishop, F., Klam, W. P., & Doan, A. P. (2015). Focus: Addiction: Case Report: Internet gaming disorder associated with pornography use. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 88(3), 319-324. [PMID]

Whang, L. S. M., Lee, S., & Chang, G. (2003). Internet over-users’ psychological profiles: A behavior sampling analysis on internet addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 6(2), 143-150. [DOI:10.1089/109493103321640338]

Wilson, K., Fornasier, S., & White, K. M. (2010). Psychological predictors of young adults’ use of social networking sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 13(2), 173-177. [DOI:10.1089/cyber.2009.0094]

Wood, R. T., Williams, R. J., & Lawton, P. K. (2007). Why do Internet gamblers prefer online versus land-based venues? Some preliminary findings and implications. Journal of Gambling Issues, 20, 235-252. [Link]

Yee, N. (2006). Motivations for play in online games. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 9(6), 772-775. [DOI:10.1089/cpb.2006.9.772]

Young, K. S. (1998a). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(3), 237-244. [DOI:10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237]

Young, K. S. (2004). Internet Addiction: A new clinical phenomenon and its consequences. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(4), 402-415. [DOI:10.1177/0002764204270278]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Cognitive Neuroscience

Received: 2021/03/24 | Accepted: 2021/05/12 | Published: 2024/07/20

Received: 2021/03/24 | Accepted: 2021/05/12 | Published: 2024/07/20

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |