Volume 16, Issue 4 (July & August 2025)

BCN 2025, 16(4): 691-700 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mansouri V, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Okhovatian F. Highlighting the Role of Neurofilament Light and Medium Polypeptides in Peripheral Diabetic Neuropathy. BCN 2025; 16 (4) :691-700

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-1945-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-1945-en.html

1- Proteomics Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Physiotherapy Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Physiotherapy Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1360 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

Full-Text:

1. Introduction

The well-known factor in the incidence of diabetes mellitus is deregulated metabolic pathways and genetic predispositions (Merchant & Klein, 2007), a disease that a vast majority of people worldwide are living with. Diabetic neuropathy (DN) is one of the most common complications of diabetes, observed in 50% of patients (Dyck et al., 1987). This disorder is a long-term complication in type I diabetic patients and, conversely, in type II diabetic individuals (Dyck et al., 1987). Initial classification of DN includes sensory-motor neuropathy and autonomic neuropathy (Boulton, 2007). DN is characterized by several processes, including progressive loss of peripheral axons, decreasing sensation, and pain feeling (Callaghan et al., 2012). The detection of DN is accompanied by irreversible damage caused by the disease (Tesfaye et al., 2010). Patients may show only one or all three types of neuropathies. Distal symmetrical neuropathy (DSN) is the most common kind of neuropathy (Bennett et al., 2014). DN can manifest as motor impairment (Ness et al., 2013), latent cardiac ischemia (Gupta & Pandit, 1992), situational hypotension (Sundaram et al., 1986), vasomotor impairment (Aso et al., 1997), increased sweating, bladder dysfunction (Gaur et al., 2000), and sexual dysfunction (Koutsojannis & Hatzilygeroudis, 2004). Careful monitoring of blood sugar and daily food care are key to preventing DN (White et al., 1981). The variety of complications from diabetes reflects the wide range of damages. The lack of knowledge about the cause of post-diabetes complications, such as DN, has increased our distance from understanding the mechanism of the disease (Shilubane & Potgieter, 2007).

Recently, biomarker discovery from the body fluids of diabetic individuals to improve the management of the patients has been implemented as an attractive approach. They use proteomic techniques as a powerful tool with high accuracy in this regard (Pasinetti et al., 2006). Although Western blot and immunohistochemistry were used for protein quantification in pathological and normal tissues; however, their inherent ability to process some proteins at a time is a part of technical limitations (Singh et al., 2009). Proteomics techniques could solve this problem by analyzing thousands of proteins quantification simultaneously. In addition, proteomics could provide information about protein structure and protein-protein interactions (Orme et al., 2010). Proteomics, with the assistance of system biology, could explore the network interaction between proteins to understand the pathophysiology of diseases (Langley et al., 2013). Most of the proteomic studies for protein quantification about DN were done using 2D-PAGE (Niederberger & Geisslinger, 2008b). It is possible to separate thousands of proteins with the 2D-PAGE technique, but the limitation to abundant and soluble proteins is inevitable (Bantscheff et al., 2007).

Meanwhile, most of the proteins in the nervous system are hydrophobic and membrane receptors (Wetterhall et al., 2011) and mass spectrometry-based proteomics could rapidly identify both heavy and low-abundant hydrophilic and hydrophobic proteins. Treatment of DN is still a challenging task. The molecular mechanism for DN is still unclear, and there are many different hypotheses about the origin of the disease (Negi et al., 2011). Genes and protein databases such as GEO are useful sources to find key genes and proteins related to DN (Li et al., 2016). Cytoscape software and STRING database are useful tools to investigate and screen the set of genes and proteins which are related to the DN (Jian & Yang, 2020; Yu et al., 2019). Numerous studies have been performed on neuropathic pain in animal models, and due to its diverse origins, changes in protein levels depend on the pain model and the time of its development. Nevertheless, several proteomic overlapping models are defined for protein expression changes and their role in neuropathic pain (Niederberger & Geisslinger, 2008a). Fundamentally categorized proteins for neuropathic pain, arranged based on their physiologic functions, as proteins related to homeostasis, neuronal functions, chaperons and heat shock proteins, proteins related to neurodegeneration and apoptosis, immune system related and signaling proteins, and neurodegenerative and regenerative proteins (Niederberger & Geisslinger, 2008a). Inhibition of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) pathway may cause DN progression in animal models (Omote et al., 2014).

Another study revealed that changes in ion channel functions and energy metabolism that are related to axon-glia interaction may cause DN development (Li et al., 2016). Chen et al. reported that “nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain like receptor 3” (NLRP3) activation mediated by signaling of ATP-P2X4 may cause inflammation related to DN (Chen et al., 2013). In vivo research suggested that knocking down micro-ribonucleic acid (RNA), miR-29c, and miR-27a could reduce DN progression (Wu et al., 2016). Scientists introduced miR-21 and miR-29 as biomarkers of DN progression (Chien et al., 2016). Demyelination is an early pathological aspect of peripheral DN (PDN) with precedes axon degeneration (Dyck & Tracy, 2018). Molecular biology of demyelination could help find biomarkers of PDN. Systematic research has investigated the relationship between the molecules that are involved in the PDN. In a study, gene expression in different DN patients was compared and concluded that the intervention genes, which are involved in DN, were associated with lipid metabolism and inflammatory reactions (Hur et al., 2011). A study based on network analysis using weighted gene databases related to DN introduced genetic differences between progressive and non-progressive types of DN (Langfelder & Horvath, 2008). Annotation methods as gene ontology or mapping genes and proteins, are helpful instruments for understanding and gaining a better view of biological features of the interest sets of proteins in DN (Doncheva et al., 2022).

The identification of interventional biomarkers in the development of diabetes and subsequently DN can help us to identify the contradictory and diverse factors of diabetes-related diseases to assist in treating them. In this study, we use existing data to try to find the key genes involved in the development of DN of the sural nerve via network analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

The gene expression dataset GSE24290 was downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) as a secondary study, which included 35 samples from patients with progressive and non-progressive sural nerve DN (SDN). The GSM597469-85 as non-progressive sural nerve and GSM597451-68 as progressive sural nerve samples were selected to analyze. The samples were statistically matched via GEO2R software. The distribution of gene expression profiles in the matched samples was median median-centered pattern. A total of 250 top-score genes (based on P) were selected to calculate the difference between progressive and non-progressive SDN groups via GEO2R. The 26 significant DEGs among the 250 DEGs were identified based on P<0.05 and FC >1.5 as cutoff criteria. The network was constructed by the 26 DEGs plus 100 first neighbors from the STRING database by Cytoscape software 3.7.2. The network analyzer application of Cytoscape was used to analyze the network. Central parameters, such as degree, betweenness centrality, closeness, and stress, were determined for the elements of the network. Meanwhile, 10% of the top nodes based on degree value were selected as hub nodes. The first 10 neighbors of the queried potent hub node were identified from the STRING database.

3. Results

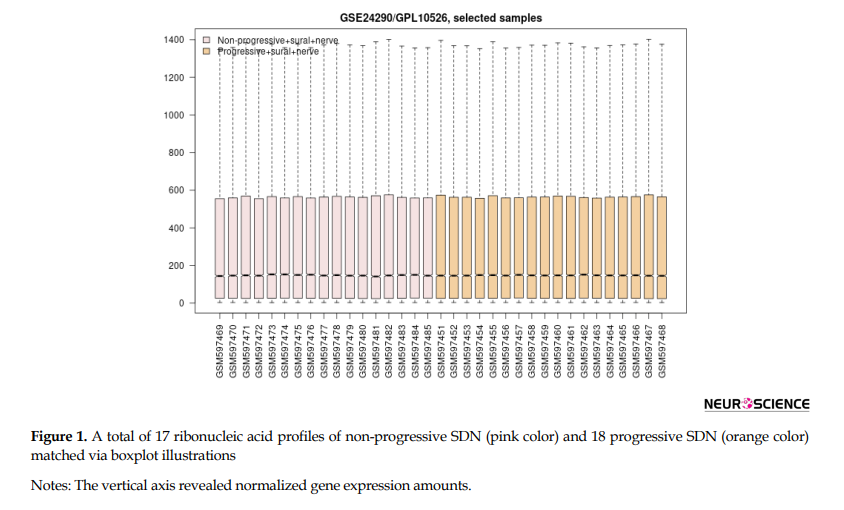

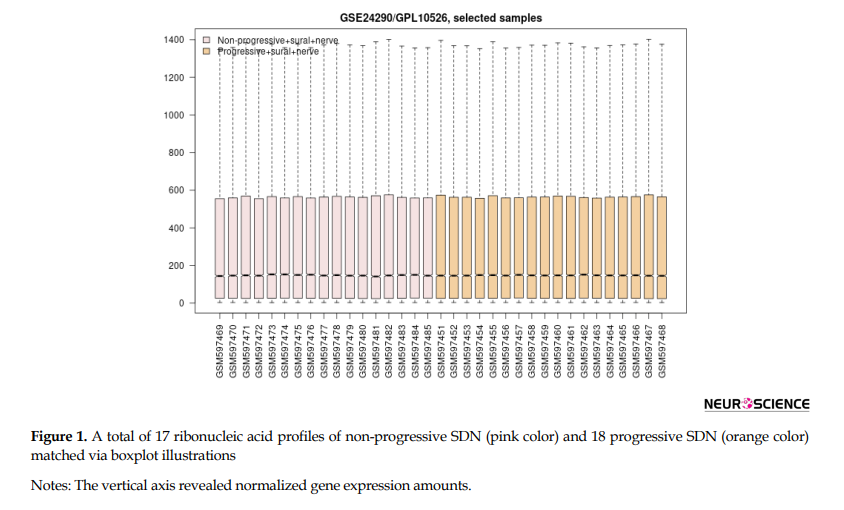

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 17 control samples (non-progressive sural nerve neuropathy) gene expression profiles matched with 18 progressive sural nerve neuropathy samples. There were aligned midpoints, demonstrating that the samples were comparable.

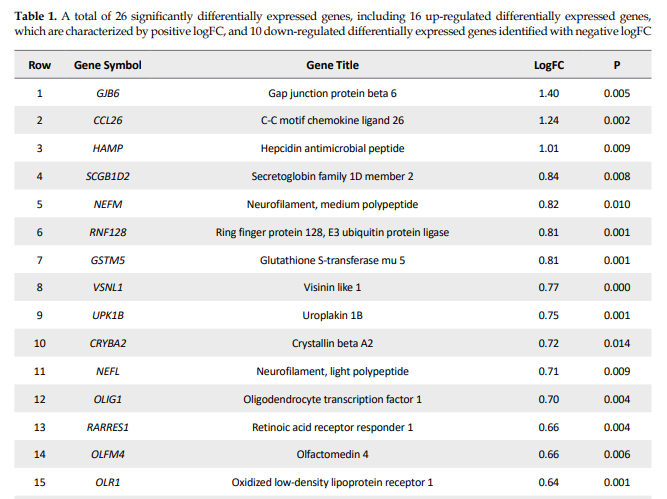

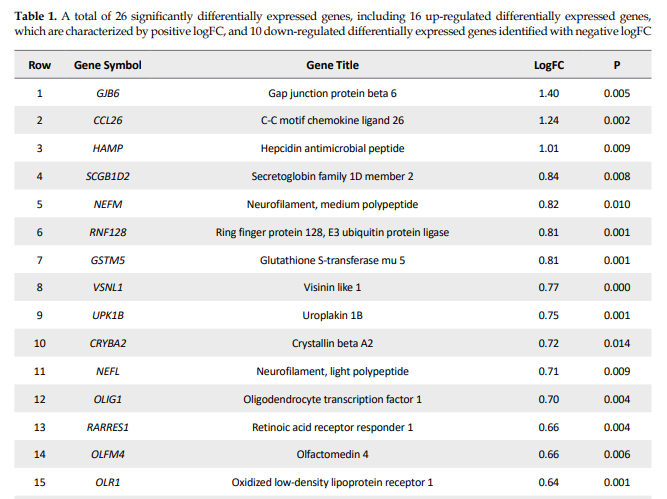

Among 250 top-score genes, 26 genes (FC ≥1.5 and P<0.05) were identified as significant DEGs (Table 1).

.PNG)

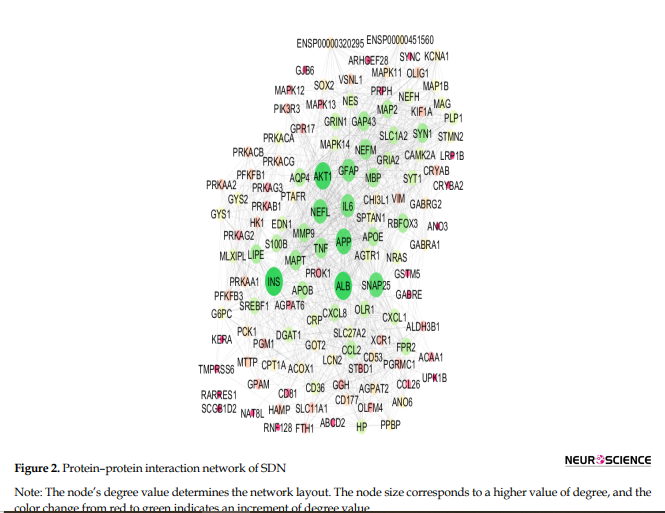

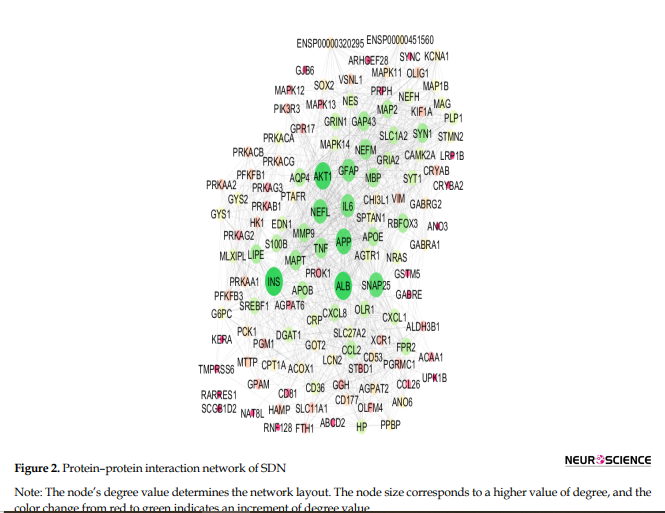

The network, including 26 DEGs plus 100 first neighbors, was constructed. The analyzed network based on degree value is shown in Figure 2.

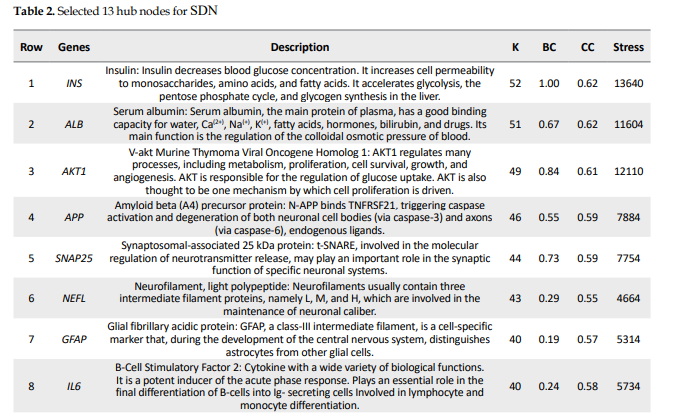

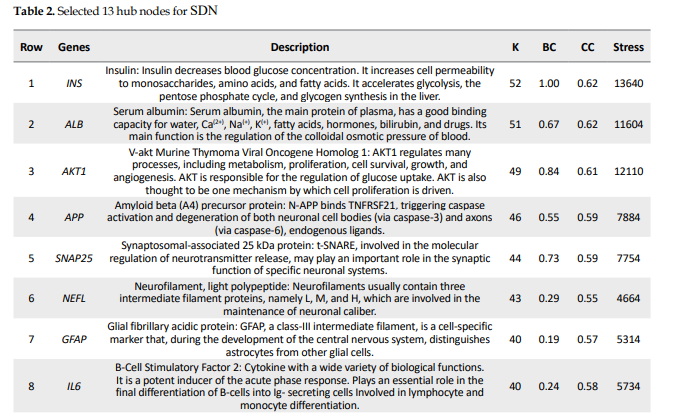

The 13 hub nodes were determined and tabulated in Table 2.

.PNG)

Among the 13 hubs, only 2 nodes are queried genes named NEFL and NEFM. The first 10 neighbors of NEFL (as the potent queried hub nodes) as an interactome are shown in Figure 3.

.PNG)

4. Discussion

This study represents a critical advancement toward identifying a specific set of genes whose expression levels are closely associated with the onset and progression of SDN. By analyzing gene interactions within known cellular pathways, we could identify common elements in this complicated network to yield novel insights into disease pathogenesis and therapeutic targets to identify potential DN biomarkers. Proteomics is a suitable screening tool for extracting a large amount of data to identify biomarkers related to PDN. A proteomic research, for example, suggested serum apolipoprotein C1 precursor for detecting and classification of DN (Tang et al., 2011). Our initial analysis of data sets classified as progression of DN. The reported data related to DN were screened by PPI network analysis to trace key related elements. The samples, including progressive and non-progressive DN, were matched as equal boxplots demonstrated in Figure 1 and statistically comparable. A total of 26 significant genes were selected considering restricted conditions for further investigations (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the two overexpressed genes were GJB6 and CCL26, respectively. The GJB6 gene, or gap junction protein beta 6, as the highest over-expressed gene (Log FC=1.4), provides instructions for making a protein named gap junction beta 6 or connexin 30. Its related pathways are gap junction trafficking and vesicle-mediated transport (Nahili et al., 2008). GJB6 upregulation in progressive DN is associated with fatty acid homeostasis and glucose homeostasis, which is confirmed by our results (Zhou & Zhang, 2019). GJB3 is an important paralog of this gene and is expressed in peripheral and auditory nerves, which could cause peripheral nerve neuropathy and auditory impairment (López-Bigas et al., 2001). The second overexpressed one was CCL26 or C-C motif chemokine ligand 26, which is a protein-coding gene involved in PEDF-induced signaling and AKD signaling. Gene ontology related to this gene has chemokine activity, and an important paralog of this gene is CCL2, which enhances microglial activation, leading to increased expression of receptor CCR2, suggesting an important role of chemokine CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 in the development of neuropathic pain (Kwiatkowski & Mika, 2014). On the other hand, two lower-expressed genes were GYS2 and PFKFB1, respectively. GYS2 is involved in glucose metabolism, and its expression is decreased in diabetic patients, which conforms to our findings (Nilsson et al., 2014). The GYS2 gene provides instructions for making liver glycogen synthase, an enzyme produced in the liver to form glycogen from glucose monomers. GYS2 plays a role in the denosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway in PDN (Zhou & Zhang, 2019). PFKFB1 (6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 1) is a protein-coding gene, and one of its related pathways is glucose metabolism. Signaling pathway of AMPK in progressive and non-progressive DN is significantly enriched with PFKFB1 and other genes as PPARG and SDC. Network analysis suggested AMPK and PPAR pathways may be implicated in DN, confirmed by our results (Li et al., 2016). Table 2 demonstrates the identified hubs that are ranked and tabulated based on degree value. Myelin formation is the result of the circumferential wrapping of Schwann cells’ cytoplasm, and it is particularly enriched with cholesterol and saturated long-chain fatty acids (Saher et al., 2011). Some researchers believed that diabetic hyperglycemia leads to malfunction in differentiation and re-differentiation of Schwann cells in accompany with myelin damage (Sango et al., 2011). New myelin formation after Schwann cells malfunction could be difficult and may cause DN progression (Cinci et al., 2015). As it is depicted in Table 2, a total of 13 nodes of the constructed network were highlighted as hub genes. Among the hub nodes (INS, ALB, AKT1, APP, Snap25, NEFL, GFAP, IL6, NEFM, TNF, MAPT, GAP43, and MBP), there are 11 first neighbors. According to the assumptions in Table 2, there are two queried hubs among the introduced hubs, including NEFL and NEFM.

According to Table 2, INS gene centrality is accompanied by degree 52, which is more than the other 12 genes. INS gene expression dysregulation following diabetes and hyperglycemia plays a critical role in disease progression. As it is shown in Table 2, INS is the potent bottleneck and is also characterized by the highest values of closeness centrality and stress. Further findings were obtained from roles of NEFM and NEFL as the only queried hub genes in progression of disease based on published documents, NEFL and NEFM encode the neurofilament proteins, and mutation of them leads to Charcot Mariye neuropathy and peripheral nerve neuropathy (Jordanova et al., 2003). Neurofilaments are intermediate filament type IV heterodimers composed of three different heavy, intermediate, and light chains, and they functionally maintain the neural caliber because neurofilaments comprise an exoskeleton (Abe et al., 2009). They may play a role in intracellular transportation into axons and dendrites. NEFL encodes light chain neurofilament protein. A mutation of this gene could cause disorders of peripheral nerves characterized by neuropathy (Drew et al., 2015). As it is demonstrated in Figure 3, NEFL and NEFM are linked with edges together, and the other 9 neighboring genes can be considered as the other related genes that have a significant impact on progressive DN incidence.

5. Conclusion

NEFL and NEFM play a critical role in the progression of DN, and more in vitro and in vivo investigations are needed to assess the specificity and sensitivity of these two highlighted differentially expressed genes in progressive DN. The investigation may result in NEFL or NEFM as biomarkers of DN.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a data-analysis with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This study was supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

References

Abe, A., Numakura, C., Saito, K., Koide, H., Oka, N., & Honma, A., et al. (2009). Neurofilament light chain polypeptide gene mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: Nonsense mutation probably causes a recessive phenotype. Journal of Human Genetics, 54(2), 94–97. [DOI:10.1038/jhg.2008.13] [PMID]

Aso, Y., Inukai, T., & Takemura, Y. (1997). Evaluation of skin vasomotor reflexes in response to deep inspiration in diabetic patients by laser doppler flowmetry: A new approach to the diagnosis of diabetic peripheral autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes Care, 20(8), 1324–1328. [DOI:10.2337/diacare.20.8.1324] [PMID]

Bantscheff, M., Schirle, M., Sweetman, G., Rick, J., & Kuster, B. (2007). Quantitative mass spectrometry in proteomics: A critical review. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 389(4), 1017-1031. [DOI:10.1007/s00216-007-1486-6] [PMID]

Bennett, G. J., Doyle, T., & Salvemini, D. (2014). Mitotoxicity in distal symmetrical sensory peripheral neuropathies. Nature Reviews Neurology, 10(6), 326-336. [DOI:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.77] [PMID]

Boulton, A. J. (2007). Diabetic neuropathy: Classification, measurement and treatment. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, 14(2), 141-145. [DOI:10.1097/MED.0b013e328014979e] [PMID]

Callaghan, B. C., Cheng, H. T., Stables, C. L., Smith, A. L., & Feldman, E. L. (2012). Diabetic neuropathy: clinical manifestations and current treatments. The Lancet Neurology, 11(6), 521-534. [DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70065-0] [PMID]

Chen, K., Zhang, J., Zhang, W., Zhang, J., Yang, J., & Li, K., et al. (2013). ATP-P2X4 signaling mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation: A novel pathway of diabetic nephropathy. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 45(5), 932-943. [DOI:10.1016/j.biocel.2013.02.009] [PMID]

Chien, H. Y., Chen, C. Y., Chiu, Y. H., Lin, Y. C., & Li, W. C. (2016). Differential microRNA profiles predict diabetic nephropathy progression in Taiwan. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 13(6), 457-465. [DOI:10.7150/ijms.15548] [PMID]

Cinci, L., Corti, F., Di Cesare Mannelli, L., Micheli, L., Zanardelli, M., & Ghelardini, C. (2015). Oxidative, metabolic, and apoptotic responses of Schwann cells to high glucose levels. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology, 29(6), 274-279. [DOI:10.1002/jbt.21695] [PMID]

Doncheva, N. T., Morris, J. H., Holze, H., Kirsch, R., Nastou, K. C., & Cuesta-Astroz, Y., et al. (2022). Cytoscape stringApp 2.0: Analysis and visualization of heterogeneous biological networks. Journal of Proteome Research, 22(2), 637-646. [DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00651]

Drew, A. P., Zhu, D., Kidambi, A., Ly, C., Tey, S., & Brewer, M. H., et al. (2015). Improved inherited peripheral neuropathy genetic diagnosis by whole‐exome sequencing. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine, 3(2), 143-154. [DOI:10.1002/mgg3.126] [PMID]

Dyck, P. J., Karnes, J. L., O'brien, P. C., Litchy, W. J., Low, P. A., & Melton Iii, L. J. (1992). The Rochester diabetic neuropathy study: Reassessment of tests and criteria for diagnosis and staged severity. Neurology, 42(6), 1164-1164. [DOI: 10.1212/WNL.42.6.1164]

Dyck, P. J. B., & Tracy, J. A. (2018). History, diagnosis, and management of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 93(6), 777–793. [DOI:10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.03.026] [PMID]

Gaur, C., Mathur, A., Agarwal, A., Verma, K., Jain, R., & Swaroop, A. (2000). Diabetic autonomic neuropathy causing gall bladder dysfunction. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 48(6), 603-605. [PMID]

Gupta, S., & Pandit, R. (1992). Silent myocardial ischaemia and cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetics. Indian Heart Journal, 44(4), 227-229. [PMID]

Hur, J., Sullivan, K. A., Pande, M., Hong, Y., Sima, A. A., Jagadish, H. V., Kretzler, M., & Feldman, E. L. (2011). The identification of gene expression profiles associated with progression of human diabetic neuropathy. Brain, 134(11), 3222-3235. [DOI:10.1093/brain/awr228] [PMID]

Jian, L., & Yang, G. (2020). Identification of key genes involved in diabetic peripheral neuropathy progression and associated with pancreatic cancer. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 13, 463. [DOI:10.2147/DMSO.S235011] [PMID]

Jordanova, A., De Jonghe, P., Boerkoel, C., Takashima, H., De Vriendt, E., & Ceuterick, C., et al. (2003). Mutations in the neurofilament light chain gene (NEFL) cause early onset severe Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Brain, 126(3), 590-597. [DOI:10.1093/brain/awg059] [PMID]

Koutsojannis, C., & Hatzilygeroudis, I. (2004). FESMI: A fuzzy expert system for diagnosis and treatment of male impotence. In: M. G. Negoita, R. J. Howlett & L.C. Jain (Eds), Knowledge-Based Intelligent Information and Engineering Systems. KES 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 3214. Berlin: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-540-30133-2_147]

Kwiatkowski, K., & Mika, J. (2014). Chemokines under neuropathic pain. Ból, 15(1), 19-35. [Link]

Langfelder, P., & Horvath, S. (2008). WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics, 9, 559. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2105-9-559] [PMID]

Langley, S. R., Dwyer, J., Drozdov, I., Yin, X., & Mayr, M. (2013). Proteomics: From single molecules to biological pathways. Cardiovascular Research, 97(4), 612-622. [DOI:10.1093/cvr/cvs346] [PMID]

Li, Y., Ma, W., Xie, C., Zhang, M., Yin, X., & Wang, F., et al. (2016). Identification of genes and signaling pathways associated with diabetic neuropathy using a weighted correlation network analysis: A consort study. Medicine, 95(47), e5443.[DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000005443] [PMID]

López-Bigas, N., Olivé, M., Rabionet, R., Ben-David, O., Martínez-Matos, J. A., & Bravo, O., et al. (2001). Connexin 31 (GJB3) is expressed in the peripheral and auditory nerves and causes neuropathy and hearing impairment. Human Molecular Genetics, 10(9), 947-952. [DOI:10.1093/hmg/10.9.947] [PMID]

Merchant, M. L., & Klein, J. B. (2007). Proteomics and diabetic nephropathy. Seminars in Nephrology, 27(6), 627–636. [DOI:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.09.003] [PMID]

Nahili, H., Ridal, M., Boulouiz, R., Abidi, O., Imken, L., & Rouba, H., et al. (2008). Absence of GJB3 and GJB6 mutations in Moroccan familial and sporadic patients with autosomal recessive non-syndromic deafness. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 72(11), 1633-1636. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.07.015] [PMID]

Negi, G., Kumar, A., Joshi, R. P., & Sharma, S. S. (2011). Oxidative stress and Nrf2 in the pathophysiology of diabetic neuropathy: Old perspective with a new angle. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 408(1), 1-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.087] [PMID]

Ness, K. K., Jones, K. E., Smith, W. A., Spunt, S. L., Wilson, C. L., & Armstrong, G. T., et al. (2013). Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptoms and functional impairment in adult survivors of extracranial solid tumors of childhood: Results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94(8), 1451-1457. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.03.009] [PMID]

Niederberger, E., & Geisslinger, G. (2008). Proteomics in neuropathic pain research. Anesthesiology, 108(2), 314-323. [DOI:10.1097/01.anes.0000299838.13368.6e] [PMID]

Niederberger, E., & Geisslinger, G. (2008). Proteomics in neuropathic pain research. Anesthesiology, 108(2), 314–323. [DOI:10.1097/01.anes.0000299838.13368.6e] [PMID]

Nilsson, E., Jansson, P. A., Perfilyev, A., Volkov, P., Pedersen, M., & Svensson, M. K., et al. (2014). Altered DNA methylation and differential expression of genes influencing metabolism and inflammation in adipose tissue from subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 63(9), 2962-2976. [DOI:10.2337/db13-1459] [PMID]

Omote, K., Gohda, T., Murakoshi, M., Sasaki, Y., Kazuno, S., & Fujimura, T., et al. (2014). Role of the TNF pathway in the progression of diabetic nephropathy in KK-Ay mice. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology, 306(11), F1335-F1347. [DOI:10.1152/ajprenal.00509.2013] [PMID]

Orme, R. P., Gates, M. A., & Fricker-Gates, R. A. (2010). A multiplexed quantitative proteomics approach for investigating protein expression in the developing central nervous system. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 191(1), 75-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.009] [PMID]

Pasinetti, G., Ungar, L., Lange, D., Yemul, S., Deng, H., & Yuan, X., et al. (2006). Identification of potential CSF biomarkers in ALS. Neurology, 66(8), 1218-1222. [DOI:10.1212/01.wnl.0000203129.82104.07] [PMID]

Saher, G., Quintes, S., & Nave, K. A. (2011). Cholesterol: A novel regulatory role in myelin formation. The Neuroscientist, 17(1), 79-93. [DOI:10.1177/1073858410373835] [PMID]

Sango, K., Yanagisawa, H., Takaku, S., Kawakami, E., & Watabe, K. (2011). Immortalized adult rodent Schwann cells as in vitro models to study diabetic neuropathy. Experimental Diabetes Research, 2011, 374943. [DOI:10.1155/2011/374943] [PMID]

Shilubane, H. N., & Potgieter, E. (2007). Patients’ and family members’ knowledge and views regarding diabetes mellitus and its treatment. Curationis, 30(2), 58-65. [DOI:10.4102/curationis.v30i2.1074] [PMID]

Singh, O. V., Yaster, M., Xu, J. T., Guan, Y., Guan, X., & Dharmarajan, A. M., et al. (2009). Proteome of synaptosome‐associated proteins in spinal cord dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury. Proteomics, 9(5), 1241-1253. [DOI:10.1002/pmic.200800636] [PMID]

Sundaram, M., Avram, D., & Cziffer, A. (1986). Unilateral ischaemic optic neuropathy following systemic hypotension. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 79(4), 250. [PMID]

Tang, W., Shi, Y., Zou, J., Chen, X., Zheng, J., & Zhao, S., et al. (2011). Serum biomarker of diabetic peripheral neuropathy indentified by differential proteomics. Frontiers in Bioscience (Landmark edition), 16(7), 2671–2681. [DOI:10.2741/3879] [PMID]

Tesfaye, S., Boulton, A. J., Dyck, P. J., Freeman, R., Horowitz, M., & Kempler, P., et al. (2010). Diabetic neuropathies: Update on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatments. Diabetes Care, 33(10), 2285-2293. [DOI:10.2337/dc10-1303] [PMID]

Wetterhall, M., Shevchenko, G., Artemenko, K., Sjödin, M. O., & Bergquist, J. (2011). Analysis of membrane and hydrophilic proteins simultaneously derived from the mouse brain using cloud-point extraction. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 400(9), 2827-2836. [DOI:10.1007/s00216-011-5037-9] [PMID]

White, N. H., Waltman, S. R., Krupin, T., & Santiago, J. V. (1981). Reversal of neuropathic and gastrointestinal complications related to diabetes mellitus in adolescents with improved metabolic control. The Journal of Pediatrics, 99(1), 41-45. [DOI:10.1016/S0022-3476(81)80954-7] [PMID]

Wu, L., Wang, Q., Guo, F., Ma, X., Ji, H., Liu, F., Zhao, Y., & Qin, G. (2016). MicroRNA-27a induces mesangial cell injury by targeting of PPARγ, and its in vivo knockdown prevents progression of diabetic nephropathy. Scientific Reports, 6, 26072. [DOI:10.1038/srep26072] [PMID]

Yu, M., Song, X., Yang, W., Li, Z., Ma, X., & Hao, C. (2019). Identify the key active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms of compound XiongShao capsule in treating diabetic peripheral neuropathy by network pharmacology approach. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2019, 5801591. [DOI:10.1155/2019/5801591] [PMID]

Zhou, H., & Zhang, W. (2019). Gene expression profiling reveals candidate biomarkers and probable molecular mechanism in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 12, 1213-1223. [DOI:10.2147/DMSO.S209118] [PMID]

The well-known factor in the incidence of diabetes mellitus is deregulated metabolic pathways and genetic predispositions (Merchant & Klein, 2007), a disease that a vast majority of people worldwide are living with. Diabetic neuropathy (DN) is one of the most common complications of diabetes, observed in 50% of patients (Dyck et al., 1987). This disorder is a long-term complication in type I diabetic patients and, conversely, in type II diabetic individuals (Dyck et al., 1987). Initial classification of DN includes sensory-motor neuropathy and autonomic neuropathy (Boulton, 2007). DN is characterized by several processes, including progressive loss of peripheral axons, decreasing sensation, and pain feeling (Callaghan et al., 2012). The detection of DN is accompanied by irreversible damage caused by the disease (Tesfaye et al., 2010). Patients may show only one or all three types of neuropathies. Distal symmetrical neuropathy (DSN) is the most common kind of neuropathy (Bennett et al., 2014). DN can manifest as motor impairment (Ness et al., 2013), latent cardiac ischemia (Gupta & Pandit, 1992), situational hypotension (Sundaram et al., 1986), vasomotor impairment (Aso et al., 1997), increased sweating, bladder dysfunction (Gaur et al., 2000), and sexual dysfunction (Koutsojannis & Hatzilygeroudis, 2004). Careful monitoring of blood sugar and daily food care are key to preventing DN (White et al., 1981). The variety of complications from diabetes reflects the wide range of damages. The lack of knowledge about the cause of post-diabetes complications, such as DN, has increased our distance from understanding the mechanism of the disease (Shilubane & Potgieter, 2007).

Recently, biomarker discovery from the body fluids of diabetic individuals to improve the management of the patients has been implemented as an attractive approach. They use proteomic techniques as a powerful tool with high accuracy in this regard (Pasinetti et al., 2006). Although Western blot and immunohistochemistry were used for protein quantification in pathological and normal tissues; however, their inherent ability to process some proteins at a time is a part of technical limitations (Singh et al., 2009). Proteomics techniques could solve this problem by analyzing thousands of proteins quantification simultaneously. In addition, proteomics could provide information about protein structure and protein-protein interactions (Orme et al., 2010). Proteomics, with the assistance of system biology, could explore the network interaction between proteins to understand the pathophysiology of diseases (Langley et al., 2013). Most of the proteomic studies for protein quantification about DN were done using 2D-PAGE (Niederberger & Geisslinger, 2008b). It is possible to separate thousands of proteins with the 2D-PAGE technique, but the limitation to abundant and soluble proteins is inevitable (Bantscheff et al., 2007).

Meanwhile, most of the proteins in the nervous system are hydrophobic and membrane receptors (Wetterhall et al., 2011) and mass spectrometry-based proteomics could rapidly identify both heavy and low-abundant hydrophilic and hydrophobic proteins. Treatment of DN is still a challenging task. The molecular mechanism for DN is still unclear, and there are many different hypotheses about the origin of the disease (Negi et al., 2011). Genes and protein databases such as GEO are useful sources to find key genes and proteins related to DN (Li et al., 2016). Cytoscape software and STRING database are useful tools to investigate and screen the set of genes and proteins which are related to the DN (Jian & Yang, 2020; Yu et al., 2019). Numerous studies have been performed on neuropathic pain in animal models, and due to its diverse origins, changes in protein levels depend on the pain model and the time of its development. Nevertheless, several proteomic overlapping models are defined for protein expression changes and their role in neuropathic pain (Niederberger & Geisslinger, 2008a). Fundamentally categorized proteins for neuropathic pain, arranged based on their physiologic functions, as proteins related to homeostasis, neuronal functions, chaperons and heat shock proteins, proteins related to neurodegeneration and apoptosis, immune system related and signaling proteins, and neurodegenerative and regenerative proteins (Niederberger & Geisslinger, 2008a). Inhibition of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) pathway may cause DN progression in animal models (Omote et al., 2014).

Another study revealed that changes in ion channel functions and energy metabolism that are related to axon-glia interaction may cause DN development (Li et al., 2016). Chen et al. reported that “nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain like receptor 3” (NLRP3) activation mediated by signaling of ATP-P2X4 may cause inflammation related to DN (Chen et al., 2013). In vivo research suggested that knocking down micro-ribonucleic acid (RNA), miR-29c, and miR-27a could reduce DN progression (Wu et al., 2016). Scientists introduced miR-21 and miR-29 as biomarkers of DN progression (Chien et al., 2016). Demyelination is an early pathological aspect of peripheral DN (PDN) with precedes axon degeneration (Dyck & Tracy, 2018). Molecular biology of demyelination could help find biomarkers of PDN. Systematic research has investigated the relationship between the molecules that are involved in the PDN. In a study, gene expression in different DN patients was compared and concluded that the intervention genes, which are involved in DN, were associated with lipid metabolism and inflammatory reactions (Hur et al., 2011). A study based on network analysis using weighted gene databases related to DN introduced genetic differences between progressive and non-progressive types of DN (Langfelder & Horvath, 2008). Annotation methods as gene ontology or mapping genes and proteins, are helpful instruments for understanding and gaining a better view of biological features of the interest sets of proteins in DN (Doncheva et al., 2022).

The identification of interventional biomarkers in the development of diabetes and subsequently DN can help us to identify the contradictory and diverse factors of diabetes-related diseases to assist in treating them. In this study, we use existing data to try to find the key genes involved in the development of DN of the sural nerve via network analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

The gene expression dataset GSE24290 was downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) as a secondary study, which included 35 samples from patients with progressive and non-progressive sural nerve DN (SDN). The GSM597469-85 as non-progressive sural nerve and GSM597451-68 as progressive sural nerve samples were selected to analyze. The samples were statistically matched via GEO2R software. The distribution of gene expression profiles in the matched samples was median median-centered pattern. A total of 250 top-score genes (based on P) were selected to calculate the difference between progressive and non-progressive SDN groups via GEO2R. The 26 significant DEGs among the 250 DEGs were identified based on P<0.05 and FC >1.5 as cutoff criteria. The network was constructed by the 26 DEGs plus 100 first neighbors from the STRING database by Cytoscape software 3.7.2. The network analyzer application of Cytoscape was used to analyze the network. Central parameters, such as degree, betweenness centrality, closeness, and stress, were determined for the elements of the network. Meanwhile, 10% of the top nodes based on degree value were selected as hub nodes. The first 10 neighbors of the queried potent hub node were identified from the STRING database.

3. Results

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 17 control samples (non-progressive sural nerve neuropathy) gene expression profiles matched with 18 progressive sural nerve neuropathy samples. There were aligned midpoints, demonstrating that the samples were comparable.

Among 250 top-score genes, 26 genes (FC ≥1.5 and P<0.05) were identified as significant DEGs (Table 1).

.PNG)

The network, including 26 DEGs plus 100 first neighbors, was constructed. The analyzed network based on degree value is shown in Figure 2.

The 13 hub nodes were determined and tabulated in Table 2.

.PNG)

Among the 13 hubs, only 2 nodes are queried genes named NEFL and NEFM. The first 10 neighbors of NEFL (as the potent queried hub nodes) as an interactome are shown in Figure 3.

.PNG)

4. Discussion

This study represents a critical advancement toward identifying a specific set of genes whose expression levels are closely associated with the onset and progression of SDN. By analyzing gene interactions within known cellular pathways, we could identify common elements in this complicated network to yield novel insights into disease pathogenesis and therapeutic targets to identify potential DN biomarkers. Proteomics is a suitable screening tool for extracting a large amount of data to identify biomarkers related to PDN. A proteomic research, for example, suggested serum apolipoprotein C1 precursor for detecting and classification of DN (Tang et al., 2011). Our initial analysis of data sets classified as progression of DN. The reported data related to DN were screened by PPI network analysis to trace key related elements. The samples, including progressive and non-progressive DN, were matched as equal boxplots demonstrated in Figure 1 and statistically comparable. A total of 26 significant genes were selected considering restricted conditions for further investigations (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the two overexpressed genes were GJB6 and CCL26, respectively. The GJB6 gene, or gap junction protein beta 6, as the highest over-expressed gene (Log FC=1.4), provides instructions for making a protein named gap junction beta 6 or connexin 30. Its related pathways are gap junction trafficking and vesicle-mediated transport (Nahili et al., 2008). GJB6 upregulation in progressive DN is associated with fatty acid homeostasis and glucose homeostasis, which is confirmed by our results (Zhou & Zhang, 2019). GJB3 is an important paralog of this gene and is expressed in peripheral and auditory nerves, which could cause peripheral nerve neuropathy and auditory impairment (López-Bigas et al., 2001). The second overexpressed one was CCL26 or C-C motif chemokine ligand 26, which is a protein-coding gene involved in PEDF-induced signaling and AKD signaling. Gene ontology related to this gene has chemokine activity, and an important paralog of this gene is CCL2, which enhances microglial activation, leading to increased expression of receptor CCR2, suggesting an important role of chemokine CCL2 and its receptor CCR2 in the development of neuropathic pain (Kwiatkowski & Mika, 2014). On the other hand, two lower-expressed genes were GYS2 and PFKFB1, respectively. GYS2 is involved in glucose metabolism, and its expression is decreased in diabetic patients, which conforms to our findings (Nilsson et al., 2014). The GYS2 gene provides instructions for making liver glycogen synthase, an enzyme produced in the liver to form glycogen from glucose monomers. GYS2 plays a role in the denosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway in PDN (Zhou & Zhang, 2019). PFKFB1 (6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 1) is a protein-coding gene, and one of its related pathways is glucose metabolism. Signaling pathway of AMPK in progressive and non-progressive DN is significantly enriched with PFKFB1 and other genes as PPARG and SDC. Network analysis suggested AMPK and PPAR pathways may be implicated in DN, confirmed by our results (Li et al., 2016). Table 2 demonstrates the identified hubs that are ranked and tabulated based on degree value. Myelin formation is the result of the circumferential wrapping of Schwann cells’ cytoplasm, and it is particularly enriched with cholesterol and saturated long-chain fatty acids (Saher et al., 2011). Some researchers believed that diabetic hyperglycemia leads to malfunction in differentiation and re-differentiation of Schwann cells in accompany with myelin damage (Sango et al., 2011). New myelin formation after Schwann cells malfunction could be difficult and may cause DN progression (Cinci et al., 2015). As it is depicted in Table 2, a total of 13 nodes of the constructed network were highlighted as hub genes. Among the hub nodes (INS, ALB, AKT1, APP, Snap25, NEFL, GFAP, IL6, NEFM, TNF, MAPT, GAP43, and MBP), there are 11 first neighbors. According to the assumptions in Table 2, there are two queried hubs among the introduced hubs, including NEFL and NEFM.

According to Table 2, INS gene centrality is accompanied by degree 52, which is more than the other 12 genes. INS gene expression dysregulation following diabetes and hyperglycemia plays a critical role in disease progression. As it is shown in Table 2, INS is the potent bottleneck and is also characterized by the highest values of closeness centrality and stress. Further findings were obtained from roles of NEFM and NEFL as the only queried hub genes in progression of disease based on published documents, NEFL and NEFM encode the neurofilament proteins, and mutation of them leads to Charcot Mariye neuropathy and peripheral nerve neuropathy (Jordanova et al., 2003). Neurofilaments are intermediate filament type IV heterodimers composed of three different heavy, intermediate, and light chains, and they functionally maintain the neural caliber because neurofilaments comprise an exoskeleton (Abe et al., 2009). They may play a role in intracellular transportation into axons and dendrites. NEFL encodes light chain neurofilament protein. A mutation of this gene could cause disorders of peripheral nerves characterized by neuropathy (Drew et al., 2015). As it is demonstrated in Figure 3, NEFL and NEFM are linked with edges together, and the other 9 neighboring genes can be considered as the other related genes that have a significant impact on progressive DN incidence.

5. Conclusion

NEFL and NEFM play a critical role in the progression of DN, and more in vitro and in vivo investigations are needed to assess the specificity and sensitivity of these two highlighted differentially expressed genes in progressive DN. The investigation may result in NEFL or NEFM as biomarkers of DN.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a data-analysis with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This study was supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

References

Abe, A., Numakura, C., Saito, K., Koide, H., Oka, N., & Honma, A., et al. (2009). Neurofilament light chain polypeptide gene mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: Nonsense mutation probably causes a recessive phenotype. Journal of Human Genetics, 54(2), 94–97. [DOI:10.1038/jhg.2008.13] [PMID]

Aso, Y., Inukai, T., & Takemura, Y. (1997). Evaluation of skin vasomotor reflexes in response to deep inspiration in diabetic patients by laser doppler flowmetry: A new approach to the diagnosis of diabetic peripheral autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes Care, 20(8), 1324–1328. [DOI:10.2337/diacare.20.8.1324] [PMID]

Bantscheff, M., Schirle, M., Sweetman, G., Rick, J., & Kuster, B. (2007). Quantitative mass spectrometry in proteomics: A critical review. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 389(4), 1017-1031. [DOI:10.1007/s00216-007-1486-6] [PMID]

Bennett, G. J., Doyle, T., & Salvemini, D. (2014). Mitotoxicity in distal symmetrical sensory peripheral neuropathies. Nature Reviews Neurology, 10(6), 326-336. [DOI:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.77] [PMID]

Boulton, A. J. (2007). Diabetic neuropathy: Classification, measurement and treatment. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity, 14(2), 141-145. [DOI:10.1097/MED.0b013e328014979e] [PMID]

Callaghan, B. C., Cheng, H. T., Stables, C. L., Smith, A. L., & Feldman, E. L. (2012). Diabetic neuropathy: clinical manifestations and current treatments. The Lancet Neurology, 11(6), 521-534. [DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70065-0] [PMID]

Chen, K., Zhang, J., Zhang, W., Zhang, J., Yang, J., & Li, K., et al. (2013). ATP-P2X4 signaling mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation: A novel pathway of diabetic nephropathy. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 45(5), 932-943. [DOI:10.1016/j.biocel.2013.02.009] [PMID]

Chien, H. Y., Chen, C. Y., Chiu, Y. H., Lin, Y. C., & Li, W. C. (2016). Differential microRNA profiles predict diabetic nephropathy progression in Taiwan. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 13(6), 457-465. [DOI:10.7150/ijms.15548] [PMID]

Cinci, L., Corti, F., Di Cesare Mannelli, L., Micheli, L., Zanardelli, M., & Ghelardini, C. (2015). Oxidative, metabolic, and apoptotic responses of Schwann cells to high glucose levels. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology, 29(6), 274-279. [DOI:10.1002/jbt.21695] [PMID]

Doncheva, N. T., Morris, J. H., Holze, H., Kirsch, R., Nastou, K. C., & Cuesta-Astroz, Y., et al. (2022). Cytoscape stringApp 2.0: Analysis and visualization of heterogeneous biological networks. Journal of Proteome Research, 22(2), 637-646. [DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00651]

Drew, A. P., Zhu, D., Kidambi, A., Ly, C., Tey, S., & Brewer, M. H., et al. (2015). Improved inherited peripheral neuropathy genetic diagnosis by whole‐exome sequencing. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine, 3(2), 143-154. [DOI:10.1002/mgg3.126] [PMID]

Dyck, P. J., Karnes, J. L., O'brien, P. C., Litchy, W. J., Low, P. A., & Melton Iii, L. J. (1992). The Rochester diabetic neuropathy study: Reassessment of tests and criteria for diagnosis and staged severity. Neurology, 42(6), 1164-1164. [DOI: 10.1212/WNL.42.6.1164]

Dyck, P. J. B., & Tracy, J. A. (2018). History, diagnosis, and management of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 93(6), 777–793. [DOI:10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.03.026] [PMID]

Gaur, C., Mathur, A., Agarwal, A., Verma, K., Jain, R., & Swaroop, A. (2000). Diabetic autonomic neuropathy causing gall bladder dysfunction. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 48(6), 603-605. [PMID]

Gupta, S., & Pandit, R. (1992). Silent myocardial ischaemia and cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetics. Indian Heart Journal, 44(4), 227-229. [PMID]

Hur, J., Sullivan, K. A., Pande, M., Hong, Y., Sima, A. A., Jagadish, H. V., Kretzler, M., & Feldman, E. L. (2011). The identification of gene expression profiles associated with progression of human diabetic neuropathy. Brain, 134(11), 3222-3235. [DOI:10.1093/brain/awr228] [PMID]

Jian, L., & Yang, G. (2020). Identification of key genes involved in diabetic peripheral neuropathy progression and associated with pancreatic cancer. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 13, 463. [DOI:10.2147/DMSO.S235011] [PMID]

Jordanova, A., De Jonghe, P., Boerkoel, C., Takashima, H., De Vriendt, E., & Ceuterick, C., et al. (2003). Mutations in the neurofilament light chain gene (NEFL) cause early onset severe Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Brain, 126(3), 590-597. [DOI:10.1093/brain/awg059] [PMID]

Koutsojannis, C., & Hatzilygeroudis, I. (2004). FESMI: A fuzzy expert system for diagnosis and treatment of male impotence. In: M. G. Negoita, R. J. Howlett & L.C. Jain (Eds), Knowledge-Based Intelligent Information and Engineering Systems. KES 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 3214. Berlin: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-540-30133-2_147]

Kwiatkowski, K., & Mika, J. (2014). Chemokines under neuropathic pain. Ból, 15(1), 19-35. [Link]

Langfelder, P., & Horvath, S. (2008). WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics, 9, 559. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2105-9-559] [PMID]

Langley, S. R., Dwyer, J., Drozdov, I., Yin, X., & Mayr, M. (2013). Proteomics: From single molecules to biological pathways. Cardiovascular Research, 97(4), 612-622. [DOI:10.1093/cvr/cvs346] [PMID]

Li, Y., Ma, W., Xie, C., Zhang, M., Yin, X., & Wang, F., et al. (2016). Identification of genes and signaling pathways associated with diabetic neuropathy using a weighted correlation network analysis: A consort study. Medicine, 95(47), e5443.[DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000005443] [PMID]

López-Bigas, N., Olivé, M., Rabionet, R., Ben-David, O., Martínez-Matos, J. A., & Bravo, O., et al. (2001). Connexin 31 (GJB3) is expressed in the peripheral and auditory nerves and causes neuropathy and hearing impairment. Human Molecular Genetics, 10(9), 947-952. [DOI:10.1093/hmg/10.9.947] [PMID]

Merchant, M. L., & Klein, J. B. (2007). Proteomics and diabetic nephropathy. Seminars in Nephrology, 27(6), 627–636. [DOI:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.09.003] [PMID]

Nahili, H., Ridal, M., Boulouiz, R., Abidi, O., Imken, L., & Rouba, H., et al. (2008). Absence of GJB3 and GJB6 mutations in Moroccan familial and sporadic patients with autosomal recessive non-syndromic deafness. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 72(11), 1633-1636. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.07.015] [PMID]

Negi, G., Kumar, A., Joshi, R. P., & Sharma, S. S. (2011). Oxidative stress and Nrf2 in the pathophysiology of diabetic neuropathy: Old perspective with a new angle. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 408(1), 1-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.087] [PMID]

Ness, K. K., Jones, K. E., Smith, W. A., Spunt, S. L., Wilson, C. L., & Armstrong, G. T., et al. (2013). Chemotherapy-related neuropathic symptoms and functional impairment in adult survivors of extracranial solid tumors of childhood: Results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94(8), 1451-1457. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.03.009] [PMID]

Niederberger, E., & Geisslinger, G. (2008). Proteomics in neuropathic pain research. Anesthesiology, 108(2), 314-323. [DOI:10.1097/01.anes.0000299838.13368.6e] [PMID]

Niederberger, E., & Geisslinger, G. (2008). Proteomics in neuropathic pain research. Anesthesiology, 108(2), 314–323. [DOI:10.1097/01.anes.0000299838.13368.6e] [PMID]

Nilsson, E., Jansson, P. A., Perfilyev, A., Volkov, P., Pedersen, M., & Svensson, M. K., et al. (2014). Altered DNA methylation and differential expression of genes influencing metabolism and inflammation in adipose tissue from subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, 63(9), 2962-2976. [DOI:10.2337/db13-1459] [PMID]

Omote, K., Gohda, T., Murakoshi, M., Sasaki, Y., Kazuno, S., & Fujimura, T., et al. (2014). Role of the TNF pathway in the progression of diabetic nephropathy in KK-Ay mice. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology, 306(11), F1335-F1347. [DOI:10.1152/ajprenal.00509.2013] [PMID]

Orme, R. P., Gates, M. A., & Fricker-Gates, R. A. (2010). A multiplexed quantitative proteomics approach for investigating protein expression in the developing central nervous system. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 191(1), 75-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.009] [PMID]

Pasinetti, G., Ungar, L., Lange, D., Yemul, S., Deng, H., & Yuan, X., et al. (2006). Identification of potential CSF biomarkers in ALS. Neurology, 66(8), 1218-1222. [DOI:10.1212/01.wnl.0000203129.82104.07] [PMID]

Saher, G., Quintes, S., & Nave, K. A. (2011). Cholesterol: A novel regulatory role in myelin formation. The Neuroscientist, 17(1), 79-93. [DOI:10.1177/1073858410373835] [PMID]

Sango, K., Yanagisawa, H., Takaku, S., Kawakami, E., & Watabe, K. (2011). Immortalized adult rodent Schwann cells as in vitro models to study diabetic neuropathy. Experimental Diabetes Research, 2011, 374943. [DOI:10.1155/2011/374943] [PMID]

Shilubane, H. N., & Potgieter, E. (2007). Patients’ and family members’ knowledge and views regarding diabetes mellitus and its treatment. Curationis, 30(2), 58-65. [DOI:10.4102/curationis.v30i2.1074] [PMID]

Singh, O. V., Yaster, M., Xu, J. T., Guan, Y., Guan, X., & Dharmarajan, A. M., et al. (2009). Proteome of synaptosome‐associated proteins in spinal cord dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury. Proteomics, 9(5), 1241-1253. [DOI:10.1002/pmic.200800636] [PMID]

Sundaram, M., Avram, D., & Cziffer, A. (1986). Unilateral ischaemic optic neuropathy following systemic hypotension. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 79(4), 250. [PMID]

Tang, W., Shi, Y., Zou, J., Chen, X., Zheng, J., & Zhao, S., et al. (2011). Serum biomarker of diabetic peripheral neuropathy indentified by differential proteomics. Frontiers in Bioscience (Landmark edition), 16(7), 2671–2681. [DOI:10.2741/3879] [PMID]

Tesfaye, S., Boulton, A. J., Dyck, P. J., Freeman, R., Horowitz, M., & Kempler, P., et al. (2010). Diabetic neuropathies: Update on definitions, diagnostic criteria, estimation of severity, and treatments. Diabetes Care, 33(10), 2285-2293. [DOI:10.2337/dc10-1303] [PMID]

Wetterhall, M., Shevchenko, G., Artemenko, K., Sjödin, M. O., & Bergquist, J. (2011). Analysis of membrane and hydrophilic proteins simultaneously derived from the mouse brain using cloud-point extraction. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 400(9), 2827-2836. [DOI:10.1007/s00216-011-5037-9] [PMID]

White, N. H., Waltman, S. R., Krupin, T., & Santiago, J. V. (1981). Reversal of neuropathic and gastrointestinal complications related to diabetes mellitus in adolescents with improved metabolic control. The Journal of Pediatrics, 99(1), 41-45. [DOI:10.1016/S0022-3476(81)80954-7] [PMID]

Wu, L., Wang, Q., Guo, F., Ma, X., Ji, H., Liu, F., Zhao, Y., & Qin, G. (2016). MicroRNA-27a induces mesangial cell injury by targeting of PPARγ, and its in vivo knockdown prevents progression of diabetic nephropathy. Scientific Reports, 6, 26072. [DOI:10.1038/srep26072] [PMID]

Yu, M., Song, X., Yang, W., Li, Z., Ma, X., & Hao, C. (2019). Identify the key active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms of compound XiongShao capsule in treating diabetic peripheral neuropathy by network pharmacology approach. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2019, 5801591. [DOI:10.1155/2019/5801591] [PMID]

Zhou, H., & Zhang, W. (2019). Gene expression profiling reveals candidate biomarkers and probable molecular mechanism in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy, 12, 1213-1223. [DOI:10.2147/DMSO.S209118] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Behavioral Neuroscience

Received: 2020/09/29 | Accepted: 2020/10/19 | Published: 2025/07/1

Received: 2020/09/29 | Accepted: 2020/10/19 | Published: 2025/07/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |