BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-1785-en.html

2- Department of Family Medicine, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Clinical Psychology, Search Results, Faculty of Psychology & Educational Sciences, Allameh Tabataba'i University, Tehran, Iran.

5- Mental Health Research Center, Tehran Institute of Psychiatry, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

● All the stages of grief can be affected by the COVID–19 quarantine policies.

● There is a need for a policy response to prevent a peak in the prevalence of mental health problems due to loss of a loved one.

● Mental health professionals should be prepared to face an upcoming wave of unresolved bereavement, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

● Mental health professionals and primary health care providers must find active cases that includes screening, diagnosis, and treatment of prolonged bereavement disorder.

● Educational campaigns and development of a new mental health workforce may be needed as a comprehensive response to the post-COVID-19 era.

Plain Language Summary

Millions of people around the world have experienced the loss of a loved one due to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Given the restrictive lockdown regulations and stay-at-home orders, most of these individuals did not get a chance to say goodbye to their loved ones, properly to have a funeral/ceremony for their loss or to bury them. As a result, millions of individuals have not experienced a regular grief cycle that enables individuals to rapidly adjust to the situation and recover themselves. In this article, first we discuss the stages of the Kübler–Ross grief cycle, and then we explain how all the stages of the grief, namely denial, anger and guilt, bargaining, depression, and acceptance can be affected by implemented quarantine policies. We then explain a phenomenon called complicated grief or prolonged bereavement disorder. Acknowledging the incredible number of families affected, we provide some recommendations for mental health policy and practice. A comprehensive response should be multi-sectoral and includes aspects, such as leadership commitment, public education, stigma reduction, increasing access to mental health resources, active case finding, and increasing the mental workforce. In the absence of a radical comprehensive mental health response, we may observe a new epidemic of mental health problems and death of despair, defined as preventable death due to high-risk behaviors, like suicide and drug use.

1. Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic drastically changed human relations in the first half of the year 2020. The fear, the lockdown orders, and social distancing qualitatively changed some aspects of human relations. For several months, people, unlike always, showed their love to their elderly by distancing from them. While the deadly virus was still spreading at the highest speed, millions of people encountered the death of their loved ones. As such, this virus (pandemic) could alter experiences of loss, grief, and bereavement at the population level. This paper discussed how the quality of our experiences of loss and grief changed during this disease. Accordingly, we made our discussion based on the Kübler-Ross model of grief (Maciejewski, Zhang, Block, & Prigerson, 2007). Kübler-Ross is one of the most widely known models of grief that has received considerable empirical clinical and epidemiological support (Maciejewski, Zhang, Block, & Prigerson, 2007). We also discuss the implication of this change in terms of public policy to maintain mental health at the population level.

2. COVID-19

In December 2019, China experienced a large outbreak of a novel coronavirus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Chatterjee et al., 2020; “COVID-19 CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC”, 2020; McHugh, Hind, Davey, & Wilson, 2019; Sohrabi Alsafi, O’Neill, Khan, Kerwan, & Al-Jabir, 2020). The virus can cause a respiratory syndrome characterized by severe pneumonia and a high fatality rate, named as COVID-19 (Borges do Nascimento et al., 2020; Wang, Wang, Ye, & Liu, 2020). By the end of April 2020, more than 200,000 deaths caused by this disease were reported worldwide. The real number may be even higher as deaths may have been systemically underestimated (Richterich, 2020). This number can reflect the minimum number of families who have lost a loved one due to COVID-19 by April 2020 (“COVID-19 CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC”, 2020). The death toll is expected to continue to rise in the coming months and some experts have warned us about a possibility of a new wave in winter 2020 (Neher, Dyrdak, Druelle, Hodcroft, & Albert, 2020).

Due to the radical and unprecedented restrictions (social distancing) in response to the pandemic, some traditional and core concepts of human lives have been shifted: death, loss, and grief. These changes challenged all sectors of society, such as public health professionals, mental health professionals, and policymakers. In this paper, we argued that the COVID-19 pandemic will result in emerging and unprecedented mental health challenges and needs. To respond properly, serious attention should be given to the prevention and reduction of COVID-19-related adverse psychological consequences. In planning and resource allocation during the COVID-19 pandemic and post-COVID-19 era, mental health should not be overlooked (Assari & Habibzadeh, 2020).

Budgets and the mental health workforce should be increased, and the consequences of failing to invest in mental health in the COVID-19 era can be a peak in depression, aggression, suicide, lack of productivity, alcohol use, drug use, and associated death of despair (as a consequence of mental health problems) (Geronimus, Bound, Waidmann, Rodriguez, & Timpe, 2019). We will argue that in the post-COVID-19 era, facing the great recession and depression (Koltai & Stuckler, 2020; Li, Wallace, & Hyde, 2019; Pruchno, Heid, & Wilson-Genderson, 2017; Rathmann, Pfortner, Elgar, Hurrelmann, & Richter, 2017; Tapia Granados & Rodriguez, 2015), the mission of mental health professionals will enter a critically important phase, if we want to prevent the occurrence of unforeseen events.

3. Loss a Risk Factor for Depression, Anxiety, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

The experience of the loss of a loved one is one of the most stressful events in a person’s life (Rafiee, Eskandari, Borjali, & Farrokhi, 2018; Simon, 2013; Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007). The epidemiological, sociological, and clinical studies also have shown the role of loss of a loved one as a major risk factor for depression (Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner, & Prescott, 2003), anxiety (Keyes, Pratt,Galea, McLaughlin, Koenen, & Shear, 2014; Kristensen, Weisaeth, Hussain, & Heir, 2015; Lenferink, Nickerson, de Keijser, Smid, & Boelen, 2020; Stroebe, Abakoumkin, & Stroebe, 2010), suicide (Heeke, Kampisiou, Niemeyer, & Knaevelsrud, 2019; Williams, Eddinger, Rynearson, & Rheingold, 2018; Zetumer et al., 2015), and substance use (Mauro, 2007).

4. Complicated Grief

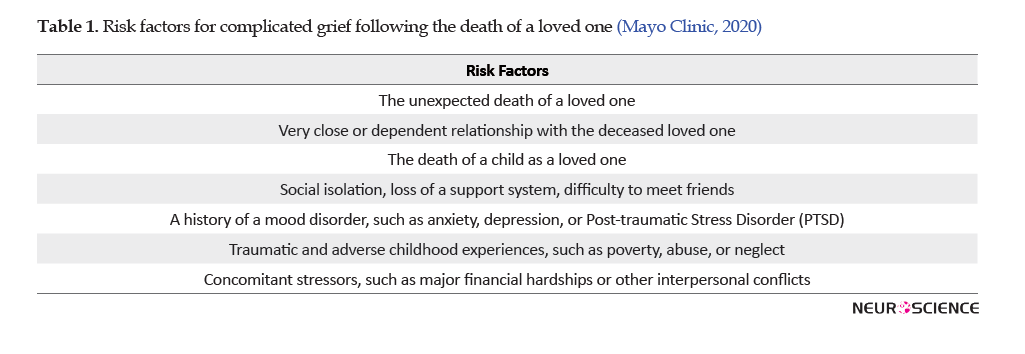

Complicated grief, also called as persistent complex bereavement disorder, is a phenomenon characterized by long-term and severe painful emotions, due to which the individual has trouble recovering from the loss of and resuming his or her normal life (Boelen & Prigerson, 2012; Boelen, Spuij, & Lenferink, 2019; Hall, Reynolds, Butters, Zisook, Simon, & Corey-Bloom, 2014; Rafiee, Eskandari, Borjali, & Farrokhi, 2019; Weber & Lehmann, 2005). Disruption of the normal grief reaction (Nakajima, 2018; Stroebe et al., 2010) is more likely to occur when the individual does not get a chance to adjust and respond to the loss or access social support. Table 1 lists the risk factors that should be screened to prevent, detect, and treat COVID-19-related complicated grief (Table 1).

5. Kübler–Ross Grief Cycle

Grief is a natural response during the death of loved ones and responses such as, denial, anger and guilt, bargaining, depression, and ultimately acceptance are the five stages of grief that are normal at the beginning of the loss of loved ones (Maciejewski, Zhang, Block, & Prigerson, 2007). Graph 1 shows a summary of the five phases of the model.

If the natural grief cycle is not taken into account and it does not go through its own period, depression, guilt, and anger in a person can turn into an adjustment or even a psychiatric problem (Boelen et al., 2019). Under general conditions, 7% (Shear, 2012) of those who experience grief suffer from unresolved bereavement and other mental health problems (Wallace, Wladkowski, Gibson, White, & Management, 2020) for various reasons, such as the inability to say goodbye to the deceased before death (Otani et al., 2017), excessive guilt (Li, Tendeiro, & Stroebe, 2019), and lack of social support (Romero, Ott, & Kelber, 2014). However, in the coronavirus pandemic and its accompanying limitations, when almost all determinants associated with unresolved bereavement affect people, and many people have to experience grief alone, this percent will certainly increase.

6. The Effects of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Grief Stages

Denial: In the first stage of grief, accompanying the body of the deceased by holding mourning ceremonies specific to their own cultures facilitate the lack of the denial of death. These conventional ceremonies that almost form our presupposition and the collective mental image of a person’s death are effective in the acceptance process (Lensing & Trauma, 2001). However, in the current situation, these practices are possible for the survivors, providing the grounds for staying in the denial stage of grief. Generally, considering the severity of the coronavirus outbreak in each region and the local laws, the conditions for accompanying the deceased person should be provided as much as possible for his/her family members. Alternatively, the conditions for the lack of denial should be facilitated for the family members by recording the film from the process of holding ceremonies. Making video or audio calls with the family members during the disease assisted by the medical staff can also facilitate the acceptance process (Francesca, 2020).

Anger: On the other hand, guilt and anger are complex issues during this pandemic because of the inability to accompany the patients in their last days of lives due to the high spread of the disease and the possible transmission of the disease from the dead cases to their relatives. Normally, holding a ceremony may reduce guilt in some cultures. The inability to hold a ceremony intensifies feelings of guilt, while it is culturally expected. The survivors’ anger also finds its object in this condition and may be directed at the government for failing to take timely action. Similarly, the person may experience anger towards other people who do not observe physical restrictions. In such conditions, giving information to survivors about the normalness of the feelings of guilt and providing the context for emotions to be expressed can be the main task at this stage. We have to inform survivors that anger is a necessary stage of the healing process and they must be willing to feel their anger, even though it may seem endless. The more they truly feel it, the more it will begin to dissipate and the more they will heal (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005).

Bargaining: In one view, the spread of the virus to the dead person can be attributed to the lack of adherence of their family members to the principles of hygiene and precautions. This view may lead to a repetition of the thoughts among survivors about what principles and actions they could have followed to prevent the death of their loved ones. This can cause negative thoughts and emotions, which complicates this period. Survivors need to know that bargaining is normal and provides a temporary escape from one’s pain through wishful thinking and hope, which gives them time to adjust to the reality of the situation (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005).

Depression: The lack of social support and the inability to hold conventional funeral ceremonies due to the limitations caused by the coronavirus pandemic make people experience this situation alone from the beginning, leading to depression. Using the only remaining means, namely social networks and making video and audio calls, can reduce the amount of loneliness that affects survivors. Additionally, planning to use a platform, such as public media can be helpful in this field (Francesca, 2020).

Acceptance: depending on individuals and other stages, it takes about 6 weeks to several months to reach this stage (Penman, Breen, Hewitt, & Prigerson, 2014), which is more achievable by the presence of social support (Marks, 2004). Considering the given problem and the unprecedented nature of the conditions, it seems a little difficult to speak about acceptance. Also, due to the high spread of the disease, the possibility of multiple deaths in a family and the existence of social stigma is a phenomenon that can make the situation harder for survivors.

7. Policy Implications

Only a comprehensive radical response may successfully address risk and first, we need the will and commitment in the policymakers. Thus, it is up to us to educate the decision-makers at global, national, and local levels. They should be informed that our emergency response should continue and shift from physical to mental recovery. If in the active phase of the epidemic, experts in communicable diseases, virologists, internists, pulmonologist, and intensive care unit experts were in the front line, after controlling the COVID-19 outbreak, psychiatrists, psychologists, consultants, and primary health care providers would become the first responders to the post-COVID-19-related mental health crisis.

Media should try to destigmatize mental health issues; therefore, people can seek care. Given that men may have a higher tendency to avoid mental health care, and given that suicide is more common in men who use more lethal means (in many cultures), men should be more considered. Elder spouses of those who have died should be more closely monitored for symptoms of depression and lack of interest. At an old age, depression may reduce the willingness to take medications and the willingness to live. Such issues may interfere with the successful disease management of the elderly who have lost a loved one. Support groups, talking with the family members and friends about bargaining hopes, and joining a support group can be helpful.

Our response should be multilayer, from case finding to increasing access to public education. It is necessary to train and inform the survivors and those around them as much as possible to use the existing structures to better deal with the emerging phenomenon. For example, holding ceremonies, such as virtual memorials in the form of virtual groups, adapting some religious and cultural customs to the structure of the virtual networks, and inviting survivors to write letters to the dead person and express their feelings can be helpful in such occasions.

Using more creative ways in this condition, such as producing memorial videos by relatives to comfort the survivors or creating a social chain based on the shared lack among the survivors of different families can help to express their shared experiences. Mental health professionals have a duty to explain and translate this phenomenon to survivors and help them to express their feelings in words and strengthen their social bonds as much as possible. In addition, this issue can be addressed seriously by mental health counseling services, which are now provided online by experts in many countries. Mental health system managers should actively trace the families of the deceased and conduct comprehensive mental health evaluations in order to actively take control measures and provide necessary interventions, as well as provide the prerequisites and different kinds of resources for delivering services, such as counseling, social support, and ultimately individual and collective therapy nationally.

8. Conclusion

In summary, communities and mental health professionals should be prepared to face an upcoming wave of unresolved bereavement and depression, and PTSD due to the complicated grief and prolonged bereavement/grief disorder. We hope that our description of the phenomenon can help policymakers recognize the situation and be prepared for an organized response.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

No ethical considerations were required in this study.

Funding

The study was conducted with no funds from external sources.

Authors' contributions

The original idea and wrote the initial topics, headlines, and the first draft: Seyede Salehe Mortazavi and Amirali Alimohamadi; Participated in the literature review, writing, editing, and revision of the paper and reached a consensus on the conclusion: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Assari, S., & Habibzadeh, P. (2020). The COVID-19 emergency response should include a mental health component. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 23(4), 281-2. [DOI:10.34172/aim.2020.12] [PMID]

Boelen, P. A., & Prigerson, H. G. (2012). Commentary on the inclusion of persistent complex bereavement-related disorder in DSM-5. Death Studies, 36(9), 771-94. [DOI:10.1080/07481187.2012.706982] [PMID]

Boelen, P. A., Spuij, M., & Lenferink, L. I. M. (2019). Comparison of DSM-5 criteria for persistent complex bereavement disorder and ICD-11 criteria for prolonged grief disorder in help-seeking bereaved children. Journal of Affective Disorders, 250, 71-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.046] [PMID]

Borges do Nascimento, I. J., Cacic, N., Abdulazeem, H. M., von Groote, T. C., Jayarajah, U., & Weerasekara, I., et al. (2020). Novel Coronavirus Infection (COVID-19) in humans: A scoping review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(4), 941. [DOI:10.3390/jcm9040941] [PMID] [PMCID]

Chatterjee, P., Nagi, N., Agarwal, A., Das, B., Banerjee, S., & Sarkar, S., et al. (2020). The 2019 novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic: A review of the current evidence. Indian Journal of Medical Research. [DOI:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_519_20] [PMID]

Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic. (2020). Retrieved from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

Francesca, I. (2020). Death in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 5(5):e258.

Geronimus, A. T., Bound, J., Waidmann, T. A., Rodriguez, J. M., & Timpe, B. (2019). Weathering, Drugs, and Whack-a-Mole: Fundamental and Proximate Causes of Widening Educational Inequity in U.S. Life Expectancy by sex and race, 1990-2015. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 60(2), 222-39. [DOI:10.1177/0022146519849932] [PMID] [PMCID]

Hall, C. A., Reynolds, C. F., Butters, M., Zisook, S., Simon, N., & Corey-Bloom, J. (2014). Cognitive functioning in complicated grief. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 58, 20-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.002] [PMID] [PMCID]

Heeke, C., Kampisiou, C., Niemeyer, H., & Knaevelsrud, C. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates of prolonged grief disorder in adults exposed to violent loss. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1583524. [DOI:10.1080/20008198.2019.1583524] [PMID] [PMCID]

Kendler, K. S., Hettema, J. M., Butera, F., Gardner, C. O., & Prescott, C. A. (2003). Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Archives Of General Psychiatry, 60(8), 789-96. [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789] [PMID]

Keyes, K. M., Pratt, C., Galea, S., McLaughlin, K. A., Koenen, K. C., & Shear, M. K. (2014). The burden of loss: unexpected death of a loved one and psychiatric disorders across the life course in a national study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(8), 864-71. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081132] [PMID] [PMCID]

Koltai, J., & Stuckler, D. (2020). Recession hardships, personal control, and the amplification of psychological distress: Differential responses to cumulative stress exposure during the U.S. Great Recession. SSM-Population Health, 10, 100521. [DOI:10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100521] [PMID] [PMCID]

Kristensen, P., Weisaeth, L., Hussain, A., & Heir, T. (2015). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment after loss of a family member: A longitudinal study after the 2004 Tsunami. Depress Anxiety, 32(1), 49-56. [DOI:10.1002/da.22269] [PMID]

Kübler-Ross, E., & Kessler, D. (2005). On grief and grieving: Finding the meaning of grief through the five stages of loss. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Lenferink, L. I. M., Nickerson, A., de Keijser, J., Smid, G. E., & Boelen, P. A. (2020). Trajectories of grief, depression, and posttraumatic stress in disaster-bereaved people. Depression and Anxiety, 37(1), 35-44. [DOI:10.1002/da.22850] [PMID] [PMCID]

Lensing, V. J. J. o. L., & Trauma. (2001). Grief support: The role of funeral service. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 6(1), 45-63. [DOI:10.1080/108114401753197468]

Li, A., Wallace, M., & Hyde, A. (2019). Degrees of inequality: The Great Recession and the college earnings premium in U.S. metropolitan areas. Social Science Research, 84, 102342. [DOI:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.102342] [PMID]

Li, J., Tendeiro, J. N., & Stroebe, M. J. I. J. O. P. (2019). Guilt in bereavement: Its relationship with complicated grief and depression. International Journal of Psychology, 54(4), 454-461. [DOI:10.1002/ijop.12483] [PMID]

Maciejewski, P. K., Zhang, B., Block, S. D., & Prigerson, H. G. (2007). An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. Journal of the American Medical Association , 297(7), 716-23. [DOI:10.1001/jama.297.7.716] [PMID]

Maciejewski, P. K., Zhang, B., Block, S. D., & Prigerson, H. G. J. J. (2007). An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(7), 716-723. [DOI:10.1001/jama.297.7.716] [PMID]

Mayo Clinic (2020). Complicated Grief. Retrieved:https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/complicated-grief/symptoms-causes/syc-20360374

Marks, A. (2004). [Understanding and working with complicated grief. The therapeutic relationship: a literature review with clinical illustrations (English)]. [MSc. thesis]. New Zealand: Auckland University of Technology.

Mauro, T. (2007). The many victims of substance abuse. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 4(9), 43-51.

McHugh, C., Hind, K., Davey, D., & Wilson, F. (2019). Cardiovascular health of retired field-based athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 7(8), 2325967119862750. [DOI:10.1177/2325967119862750] [PMID] [PMCID]

Nakajima, S. (2018). Complicated grief: Recent developments in diagnostic criteria and treatment. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1754):20170273. [DOI:10.1098/rstb.2017.0273] [PMID] [PMCID]

Neher, R. A., Dyrdak, R., Druelle, V., Hodcroft, E. B., & Albert, J. (2020). Potential impact of seasonal forcing on a SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Swiss Medical Weekly, 150, w20224. [DOI:10.4414/smw.2020.20224]

Otani, H., Yoshida, S., Morita, T., Aoyama, M., Kizawa, Y., & Shima, Y., et al. (2017). Meaningful communication before death, but not present at the time of death itself, is associated with better outcomes on measures of depression and complicated grief among bereaved family members of cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(3), 273-279. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.010] [PMID]

Penman, E. L., Breen, L. J., Hewitt, L. Y., & Prigerson, H. G. J. D. S. (2014). Public attitudes about normal and pathological grief. Death Studies, 38(8), 510-516. [DOI:10.1080/07481187.2013.873839] [PMID]

Pruchno, R., Heid, A. R., & Wilson-Genderson, M. (2017). The Great Recession, Life Events, and Mental Health of Older Adults. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 84(3), 294-312. [DOI:10.1177/0091415016671722] [PMID]

Rafiee, M., Eskandari, H., Borjali, A., & Farokhi, N. (2019). Investigation on Experienced losses in the life story of young people living in Tehran: A phenomenological study. Counseling Culture and Psychotherapy, 10, 63-98.

Rafiee, M., Eskandari, H., Borjali, A., & Farrokhi, N. J. J. O. R. I. P. H. (2018). Reaction to loss among young generation of tehran’s population: A qualitative study. Journal of Research in Psychological Health, 12(3), 75-90.

Rathmann, K., Pfortner, T. K., Elgar, F. J., Hurrelmann, K., & Richter, M. (2017). The great recession, adolescent smoking, and smoking inequalities: What role does youth unemployment play in 24 european countries? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(11), 1284-91. [DOI:10.1093/ntr/ntw298] [PMID]

Richterich, P. (2020). Severe underestimation of COVID-19 case numbers: effect of epidemic growth rate and test restrictions. medRxiv, 2020.2004.2013.20064220. [DOI:10.1101/2020.04.13.20064220]

Romero, M. M., Ott, C. H., & Kelber, S. T. J. D. s. (2014). Predictors of grief in bereaved family caregivers of person’s with Alzheimer’s disease: A prospective study. Death Studies, 38(6), 395-403. [DOI:10.1080/07481187.2013.809031] [PMID]

Shear, M. K. J. D. I. C. N. (2012). Grief and mourning gone awry: pathway and course of complicated grief. Death Studies, 14(2), 119.

Simon, N. M. J. J. (2013). Treating complicated grief. Journal of the American Medical Association, 310(4), 416-23. [DOI:10.1001/jama.2013.8614] [PMID] [PMCID]

Sohrabi, C., Alsafi, Z., O’Neill, N., Khan, M., Kerwan, A., & Al-Jabir, A. (2020). World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). International Journal of Surgery, 76, 71-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034] [PMID] [PMCID]

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Stroebe, W. J. T. L. (2007). Health outcomes of bereavement. The Lancet, 370(9603):1960-73 [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9]

Stroebe, W., Abakoumkin, G., & Stroebe, M. (2010). Beyond depression: yearning for the loss of a loved one. Omega (Westport), 61(2), 85-101. [DOI:10.2190/OM.61.2.a] [PMID]

Tapia Granados, J. A., & Rodriguez, J. M. (2015). Health, economic crisis, and austerity: A comparison of Greece, Finland and Iceland. Health Policy, 119(7), 941-53. [DOI:10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.04.009] [PMID]

Wallace, C. L., Wladkowski, S. P., Gibson, A., White, P. J. J. o. P., & Management, S. (2020). Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: Considerations for palliative care providers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1):e70–e6. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012] [PMID] [PMCID]

Wang, L., Wang, Y., Ye, D., & Liu, Q. (2020). Review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) based on current evidence. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 55(6), 105948. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105948] [PMID] [PMCID]

Weber, S., & Lehmann, E. (2005). Abnormal responses to the loss of a loved one. MMW Fortschritte der Medizin, 147(6), 36-37.

Williams, J. L., Eddinger, J. R., Rynearson, E. K., & Rheingold, A. A. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation in a treatment-seeking sample of violent loss survivors. Crisis, 39(5), 377-85. [DOI:10.1027/0227-5910/a000520] [PMID]

Zetumer, S., Young, I., Shear, M. K., Skritskaya, N., Lebowitz, B., & Simon, N. (2015). The impact of losing a child on the clinical presentation of complicated grief. Journal of Affective Disorders, 170, 15-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.021] [PMID] [PMCID]

Received: 2020/05/8 | Accepted: 2020/06/9 | Published: 2020/07/8

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |