Volume 12, Issue 2 (March & April 2021)

BCN 2021, 12(2): 213-222 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nekouei M, Aliahmadi A, Kiaei M, Ghassempour A R. Mutant Profilin1 Aggregation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: An in Vivo Biochemical Analysis. BCN 2021; 12 (2) :213-222

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-1383-en.html

URL: http://bcn.iums.ac.ir/article-1-1383-en.html

1- Department of Phytochemistry, Medicinal Plants and Drugs Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Biology, Medicinal Plants and Drugs Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Department of Neurology, Department of Geriatrics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, USA.

2- Department of Biology, Medicinal Plants and Drugs Research Institute, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Department of Neurology, Department of Geriatrics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, USA.

Full-Text [PDF 1717 kb]

| Abstract (HTML)

PFN1, a ubiquitously expressed protein in most cell and tissue types, is best known for its ability to bind G-actin via its actin-binding domain and regulate actin polymerization (Alkam, Feldman, Singh, & Kiaei, 2017). Besides being involved in cytoskeletal organization, this protein has over 50 ligands and binding partners, suggesting that it has multiple other functions. Most ligands were found to bind to PFN1 Poly-L-Proline (PLP)-binding domain, which is different from the actin-binding site. The PFN1 protein identified in various organisms is highly conserved not only in primary sequence but also in protein folding (Jockusch, Murk, & Rothkegel, 2007; Witke, 2004). Single amino acid mutation in each binding site was found to alter the secondary and tertiary structures of folded PFN1 protein that may impair the interaction of PFN1 with its ligands (Boopathy et al., 2015; Del Poggetto, Bemporad, Tatini, & Chiti, 2015; Del Poggetto, Gori, & Chiti, 2016; Nekouei et al., 2018). Moreover, these structural alterations are consistent with aggregation propensities of ALS-linked mutant PFN1 proteins studied in vivo and in vitro (Del Poggetto et al., 2018; Fil et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2016). The cytoplasmic aggregate of PFN1 can also include other functional proteins that may play critical roles in the mechanism of ALS. The protein co-aggregation may contain soluble proteins (Bondarev, Antonets, Kajava, Nizhnikov, & Zhouravleva, 2018) interacting with PFN1 by a specific binding site which may result in distinct cellular defects that contribute to the pathogenesis of motor neuron degeneration in ALS. As reported previously, PFN1 protein interacts with endogenous TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) (Tanaka, Nonaka, Suzuki, Kametani, & Hasegawa, 2016). ALS-linked mutant PFN1 may serve as inclusion bodies that initiate the formation of TDP-43 aggregates by sequestration of TDP-43 into PFN1 aggregates (positive for ubiquitin and p62) and its conversion to prion-like species, which imply the association of mutant PFN1 toxicity with TDP-43 function (Tanaka & Hasegawa, 2016; Tanaka et al., 2016).

To gain insight into the mechanism of ALS, various mouse models have been generated using some of the identified ALS causative genes, among which the most widely used is SOD1-based mouse models (Philips & Rothstein, 2015). Transgenic mouse lines overexpressing hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V produced recently (Fil et al., 2017) can also be used to study the molecular behavior of mutant PFN1 and understand its role in ALS. According to the previous studies, the G118V mutation, which is located most proximal to the actin-binding site, affects actin polymerization that may become unable to bind actin. Moreover, this mutant variant forms aggregates in vivo (neuronal cytoplasm) and in vitro (Brettle, Suchowerska, Chua, Ittner, & Fath, 2015; Fil et al., 2017; Freischmidt et al., 2015; Nekouei et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2012). Hence, this mutation can be an excellent model to study the mechanism of PFN1 neurotoxicity in ALS. In this study, we investigated the aggregation of hPFN1 protein using tissue homogenates of PFN1 mouse models by immunoblotting. The insoluble fractions of the brain and spinal cord homogenates from transgenic (hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V) and non-transgenic mice showed that only mutant PFN1 could form aggregate, not wild type and non-transgenic controls. Additionally, we expressed and purified wild type and mutant (G118V) His6-tagged PFN1 to identify additional candidate proteins in the insoluble fraction from the spinal cord by using a pull-down assay.

2. Methods

2.1. Transgenic mice

As described previously (Fil et al., 2017), transgenic (hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V) mice were generated, and the selected mice with and without ALS-like symptoms were genotyped to determine the presence of the transgene. All the animal work was approved by UAMS IACUC (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees) and carried out accordingly. Tissues used in this study were the tissue samples from mutant and wild-type PFN1 mice that were previously isolated as part of the research described in Fil et al. (2017) and were stored for further use. To analyze the expression level of hPFN1 in the tissues from these mice, brain, spinal cord, liver, and leg muscles were isolated and stored at -80°C till use. Then the frozen tissues were thawed out on the ice, and the whole brain, spinal cord, liver, and leg muscles were homogenized with RIPA buffer. After estimating protein concentration, an aliquot was mixed with sample buffer (Invitrogen), heated at 90°C for 10 min, and run on 4%-12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen). Then the separated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. Anti-PFN1 and anti-β-actin (Sigma Aldrich) were the primary antibodies followed by appropriate secondary antibodies.

2.2. Soluble and insoluble fractionation and western blotting

Previously isolated tissue samples from non-transgenic and transgenic (hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V) mice stored at -80°C as described in Fil et al. (2017) were thawed out on the ice. The motor cortex was dissected out from the whole brain. The remaining parts of the brain (referred to as the brain without motor cortex) and spinal cord were lysed for fractionation into soluble and insoluble proteins. Isolated tissues were homogenized in NP-40 lysis buffer containing (1% NP-40, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate) with EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche). The lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 13500 rpm for 20 min at 4°C to separate the supernatant as the soluble fraction. After washing the remaining pellet twice with lysis buffer, it was resuspended in NP-40 lysis buffer plus 8 M urea/3% SDS and sonicated on ice. Further, the samples were incubated on ice for 1 hour and again centrifuged (13500 rpm, 20 min, and 4°C) to remove the supernatant as an insoluble fraction. After determining protein concentration by BCA assay, 20 µg of each sample, mixed with sample buffer (Invitrogen) with and without reducing agent, was run on 4–12% gradient NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen). The proteins separated on the SDS-PAGE were transferred to the PVDF membrane using Invitrogen iBlot device. The blotted membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS-T (0.1% Tween 20) buffer for 1 hour, and then incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibodies, including anti-PFN1 (Sigma Aldrich #P7749 and Abcam #ab50667) diluted (1:1000) in PBS-T 5% milk. After rinsing the blots with PBS-T buffer, they were incubated in HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham Corp.) for 1 hour, followed by washing with PBS-T buffer. Finally, proteins were visualized using the ECLdetection system (Amersham Corp.).

2.3. Cloning and purification of recombinant His6-tagged PFN1

Plasmid DNA constructs for human His6-tagged PFN1, both wild type (PFN1WT) and mutant (PFN1G118V), were kindly gifted by Prof. Weishaupt laboratory at the University of Ulm, Germany, as described in Freischmidt et al. (2015) (Freischmidt et al., 2015). His6-PFN1 was expressed for 4 hours upon IPTG (SinaClon) induction (1 mM) at 37°C in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen). Bacterial cells were collected and sonicated in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl and 500 mM NaCl buffer with 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) containing EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche). After removing the bacterial cell debris by centrifugation (11000g, 20 min), the supernatant was subjected to Ni–NTA Agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific), pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer. Recombinant His6-PFN1 was purified under native conditions in a batch mode, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Buffers containing (20 mM Tris-HCl and 500 mM NaCl) with 25 mM and 250 mM imidazole at pH 7.5 were used as wash and elution buffers, respectively. The expression and proteomic identification of recombinant His6-PFN1 proteins were assessed by SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF, as reported in our previous work (Nekouei et al., 2018).

2.4. Pull-down assay

For pull-down assay (Louche, Salcedo, & Bigot, 2017), purified His6-tagged PFN1G118V in lysis buffer was incubated with equilibrated Ni-NTA Agarose beads for 2 hours at 4°C with constant rotation. After centrifugation of flow through at 700g for 1 min, insoluble fraction of spinal cord lysate from transgenic (hPFN1G118V) mice was diluted, added to the column, and further incubated for 2 hours. Then, the beads were washed with wash buffer, and finally, interacting proteins were eluted from the column with elution buffer, as described above. To eliminate nonspecific interaction of proteins with beads, the spinal cord lysate without His6-tagged PFN1 was used as the negative control. Samples were run on 15% SDS-PAGE according to Laemmli protocol (Laemmli, 1970) and detected by Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 or silver nitrate staining.

The protein bands of interest were excised from the Coomassie blue-stained gels and digested in-gel with trypsin. Then, MALDI mass spectrometry (Applied Biosystems 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF) in positive reflector mode was used to analyze the digested proteins as described previously (Nekouei et al., 2018; Shevchenko,Tomas, Havlis, Olsen, & Mann, 2007). Before MALDI analysis, equal volumes of the resulting peptide mixtures and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix solution were thoroughly mixed, and then 1 μL of the solution was deposited on a MALDI plate. The mass analysis was followed by data processing of the monoisotopic peptide mass values of tryptic peptides using the MASCOT peptide mass fingerprinting program to identify the proteins. All reagents used in this section were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

3. Results

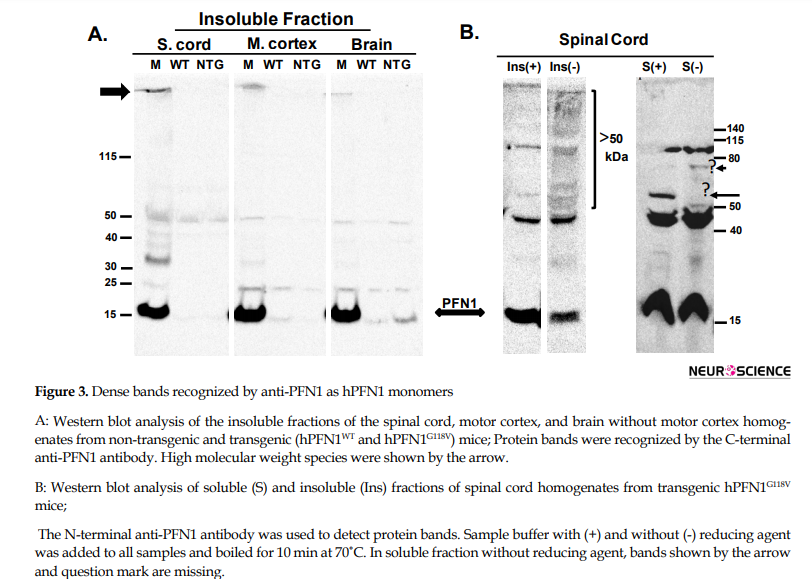

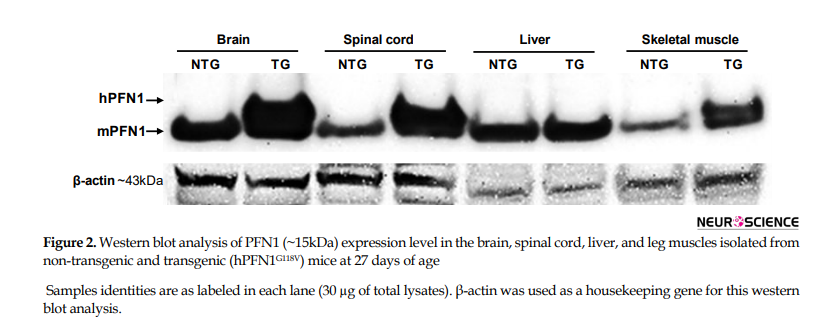

The transgenic mutant PFN1 mice, which we have created, developed ALS-like phenotypes and pathologies (Fil et al., 2017). Here, we have studied the effect of mutant PFN1 further. We found that hPFN1 (WT or G118V) driven by prion promoter is selectively expressed in the brain, spinal cord, and leg muscles of transgenic mice compared with non-transgenic, whereas no expression of hPFN1 was observed in the liver of these mice (Figure 2). The ALS-causing mutations in PFN1 are supposed to affect the PFN1 protein folding and 3D-structural assembly that drive the mutant PFN1 to aggregate. We have found evidence of aggregation of PFN1 in our mutant PFN1 mice and reported this initially in Fil et al. (2017). To further investigate the mechanism of PFN1 aggregation in vivo, we lysed the spinal cord, motor cortex, and brain without motor cortex of non-transgenic and transgenic (hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V) mice with a buffer containing mild non-ionic detergent (NP-40). Western blot analysis of soluble fractions, separated from insoluble proteins by centrifugation, showed the presence of PFN1 proteins in all tissue homogenates. As shown in Figure 3A, dense bands recognized by anti-PFN1 as hPFN1 monomers are detected in the insoluble fractions of the spinal cord, motor cortex, and brain without motor cortex of mutant transgenic mice; whereas no monomeric bands of hPFN1 protein were detected in the insoluble fractions of wild type and non-transgenic controls.

Besides, we observed other bands with higher molecular weights ranging from 30-50 kDa (likely to be dimers and trimers of PFN1) in the insoluble fraction of the spinal cord compared with the insoluble fractions of the motor cortex and brain without motor cortex isolated from transgenic (hPFN1G118V) mice. These bands, along with high molecular weight species, were retained in the stacking gel (shown by an arrow), represent stable interactions against urea, detergents, and reducing agents (Figure 3A).

The soluble and insoluble fractions obtained from spinal cord homogenate were subjected to SDS-PAGE with and without reducing agent in the loading sample buffer (Figure 3B). Migration pattern based on reducing and non-reducing conditions is different and reveals new protein aggregation and complexes with PFN1. Proteins with molecular weights heavier than 40 kDa are more abundant in insoluble fractions of hPFN1G118V mice spinal cord without reducing agent vs. soluble fraction and insoluble fractions in the presence of reducing agent. We also observe smears of hPFN1G118V proteins that may indicate oligomers and represent the formation of disulfide bonds in the absence of Dithiothreitol (DTT) as a reducing agent. Interestingly, there is a difference between the blots of the two soluble fractions in the number of visible bands shown by arrows (Figure 3B).

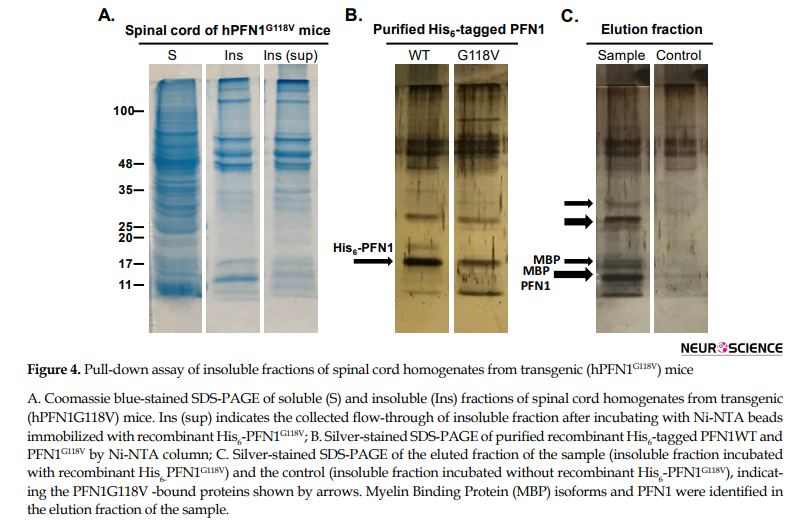

As shown by SDS-PAGE in Figure 4A, we did not observe identical protein distributions in the soluble and insoluble fractions of the hPFN1G118V mice spinal cord. Prominent bands detected on SDS-PAGE of the insoluble fraction may be complexes of PFN1 protein and other proteins entrapped in the aggregation.

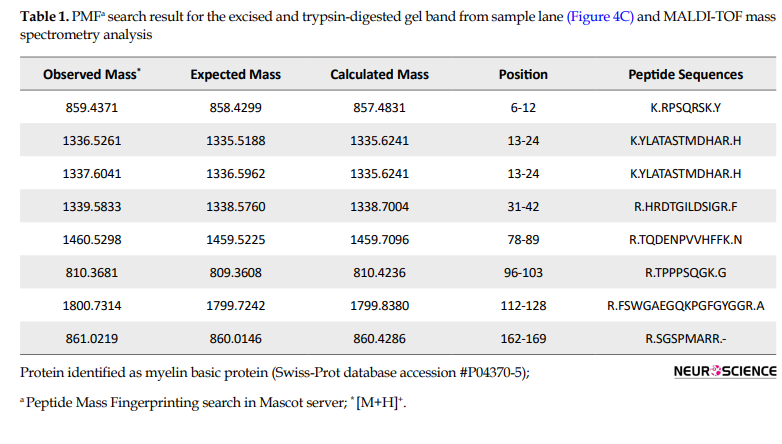

To identify what could be in the aggregate complex, we performed a pull-down assay using recombinant His6-PFN1G118V. We used a negative control column without recombinant His6-PFN1G118V to eliminate the nonspecific interacting proteins of spinal cord insoluble fraction with the affinity chromatography resin. Further, the purified Ni-NTA column again under pull-down assay condition to control for any co-purified, nonspecific host cell proteins. The arrows in Figure 3C points to PFN1-bound protein bands that are present in the eluted fraction of the sample, whereas almost none were detected in the eluted fraction of the controls. Before Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI)-Time-of-Flight (TOF) analysis of proteins, the differential protein bands were excised from the polyacrylamide gels and processed with in-gel digestion. The detected peptide masses were searched against non-redundant protein sequence databases (NCBI) using the Mascot search program. These analyses enabled us to reveal that hPFN1 is one of the proteins in the insoluble fraction which interacts with recombinant His6-PFN1G118V. These data confirm that mutant PFN1 proteins tend to interact with each other and form aggregates. Furthermore, we found that Myelin Basic Protein (MBP) is present in the complex with a score of 80 and 44% sequence coverage (Table 1).

MBP is an essential protein involved in forming and stabilizing myelin membranes in the Central Nervous System (CNS) (Boggs, 2006). Coincidentally, while searching the literature, we saw a previously published study that described that the prion-like aggregation of MBP formed during demyelination might contribute to the neurotoxicity mechanism of multiple sclerosis (Frid et al., 2015). Hence, the presence of MBP in the insoluble fraction of the ALS-linked spinal cord is of great importance and may be relevant to the loss of motor neurons in ALS.

4. Discussion

Different identified mutations located in actin- and PLP-binding sites of PFN1 protein (Figure 1) may impact various functions of PFN1, leading to ALS disease by diverse neurotoxicity mechanisms. Of those, the expression of hPFN1C71G and hPFN1G118V in two recently generated transgenic mice models displayed ALS-like phenotypes, spinal cord motor neuron degeneration, and aggregation of mutant PFN1 (Fil et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2016). As shown in Figure 2, mutant PFN1 has been primarily expressed in the CNS (brain and spinal cord) region: two major organs implicated in ALS disease.

Based on these results, we further confirmed the aggregation of mutant PFN1 and observed higher molecular weight complexes in the spinal cord, brain without motor cortex, and motor cortex tissues obtained from transgenic (hPFN1G118V) mice compared with wild type and non-transgenic mice (Figure 3). The accumulation of larger forms of PFN1 in the insoluble protein aggregate might be because of their more resistance to the degradation process. Our previous finding can support this hypothesis that a thick smear of ubiquitinated proteins larger than 50 kDa was found in the insoluble fraction of hPFN1G118V mice relative to wild type and non-transgenic (Fil et al., 2017). Our preliminary western blot analysis also revealed that mutant PFN1 form aggregate in the lumbar spinal cord was significantly higher in full-symptomatic and end-stage disease (Fil et al., 2017). These results are consistent with previous findings in vitro and in mammalian cells, confirming the aggregation tendency of mutant PFN1 relative to wild type (Alkam et al., 2017).

In this work, we have used two different anti-PFN1 antibodies, C-terminal and N-terminal, which exhibited different banding patterns (Figures 3A and B). As shown in Figure 3A, prominent bands of mutant PFN1 dimer and high molecular weight proteins were recognized by C-terminal anti-PFN1 antibody in the insoluble fraction of transgenic (hPFN1G118V) mice. This can be the consequence of conformational and structural alteration that occurred in PFN1G118V (Del Poggetto et al., 2015; Nekouei et al., 2018). Our recent in silico study reveals the impact of mutations on the amino acids near the mutation sites (Kiaei et al., 2018). We conclude that the substitution of glycine to valine enhances the hydrophobicity and the rigidity of the actin-interacting loop region. In that report, our results showed that mutant forms of PFN1 had different fluctuation patterns and salt bridges and hydrogen bond formation between critical residues, compared to wild type (Kiaei et al., 2018). Therefore, we propose that the single amino acid mutation of PFN1 (e.g. G118V) may cause ALS by losing normal function and or by the gain of toxicity. Based on our biochemical analysis of the hPFN1G118V spinal cord, different protein profiles were observed in the soluble and insoluble fractions due to the toxicity and aggregation of PFN1. The result of the pull-down assay can shed light on whether mutant PFN1 can interact with other proteins and form aggregates. Among the detected co-aggregated proteins shown in Figure 4, the bands corresponding to MBP, a critical protein in the CNS myelination, were more abundant on the silver nitrate stained gel. Based on the literature, MBP is a multifunctional protein like PFN1, which interacts in vitro with cytoskeletal proteins, including actin, and causes actin polymerization and bundling of microfilaments (Harauz, Ladizhansky, & Boggs, 2009). We recently reported that separation and vacuolization of the myelin sheath is one of the cellular abnormalities that occur in the ventral root motor axons of hPFN1G118V transgenic mice (Fil et al., 2017). Additionally, degenerating myelinated axons and glia containing phagocytized myelin were found in sciatic nerves of end-stage hPFN1G118V transgenic mice (Fil et al., 2017).

Protein aggregation is the hallmark of all neurodegenerative diseases. Thus the investigation of the aggregation of mutant PFN1 in the brain and spinal cord of the ALS mouse model may provide new clues on how PFN1 contributes to the loss of upper (corticospinal motor neurons in layer V) and lower (ventral horn) motor neurons in hPFN1G118V mice. This study suggests that the proteinopathy of mutant PFN1 maybe a critical cause of neuronal stress and death. High molecular weight bands detected with anti-PFN1 may also indicate oligomers’ formation with their PFN1 and complexes appearance with other proteins.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University Research Council.

Funding

This study was supported by the Shahid Beheshti University Research Council. This work was also supported by grants to MK from the UAMS startup fund, UAMS Center for Translational Neurosciences, NIGMS IDeA Program Award P30 GM110702, P20GM109005, and NINDS NS088653 and NS101334.

Authors' contributions

Experimental studies, data analysis, and writing – original draft: Mina Nekouei; Sub-cloning and the expression of PFN1 proteins: Atousa Aliahmadi; Supervision, writing – review & editing: Mahmoud Kiaei and Alireza Ghassempour; Conceptualization, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Kiaei and UAMS have a financial interest in the technology discussed in this paper. These budgetary interests have been reviewed and affirmed as per the UAMS conflict of interest policies. Other authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Shahid Beheshti University Research Council for its financial support.

References

Al-Chalabi, A., van den Berg, L. H., & Veldink, J. (2017). Gene discovery in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Implications for clinical management. Nature Reviews Neurology, 13(2), 96-104. [DOI:10.1038/nrneurol.2016.182] [PMID]

Alkam, D., Feldman, E. Z., Singh, A., & Kiaei, M. (2017). Profilin1 biology and its mutation, actin(g) in disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 74(6), 967-81. [DOI:10.1007/s00018-016-2372-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

Boggs, J. (2006). Myelin basic protein: A multifunctional protein. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 63(17), 1945-61. [DOI:10.1007/s00018-006-6094-7] [PMID]

Bondarev, S., Antonets, K., Kajava, A., Nizhnikov, A., & Zhouravleva, G. (2018). Protein co-aggregation related to amyloids: methods of investigation, diversity, and classification. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(8), 2292.[DOI:10.3390/ijms19082292] [PMID] [PMCID]

Boopathy, S., Silvas, T. V., Tischbein, M., Jansen, S., Shandilya, S. M., & Zitzewitz, J. A., et al. (2015). Structural basis for mutation-induced destabilization of profilin 1 in ALS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(26), 7984-89. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1424108112] [PMID] [PMCID]

Brettle, M., Suchowerska, A. K., Chua, S. W., Ittner, L. M., & Fath, T. (2015). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated mutant profilin 1 increases dendritic arborisation and spine formation in primary hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience Letter, 609, 223-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2015.09.034] [PMID]

Chen, Y., Zheng, Z. Z., Huang, R., Chen, K., Song, W., & Zhao, B., et al. (2013). PFN1 mutations are rare in Han Chinese populations with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiology of Aging, 34(7), 1922-e1. [DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.01.013] [PMID]

Del Poggetto, E., Bemporad, F., Tatini, F., & Chiti, F. (2015). Mutations of Profilin-1 associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis promote aggregation due to structural changes of its native state. ACS Chemical Biology, 10(11), 2553-63. [DOI:10.1021/acschembio.5b00598] [PMID]

Del Poggetto, E., Gori, L., & Chiti, F. (2016). Biophysical analysis of three novel profilin-1 variants associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis indicates a correlation between their aggregation propensity and the structural features of their globular state. Biological Chemistry, 397(9), 927-37. [DOI:10.1515/hsz-2016-0154] [PMID]

Del Poggetto, E., Toto, A., Aloise, C., Di Piro, F., Gori, L., & Malatesta, F., et al. (2018). Stability of an aggregation-prone partially folded state of human profilin-1 correlates with aggregation propensity. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 293(26), 10303-1031. [DOI:10.1074/jbc.RA118.002087] [PMID] [PMCID]

Fil, D., DeLoach, A., Yadav, S., Alkam, D., MacNicol, M., & Singh, A., et al. (2017). Mutant Profilin1 transgenic mice recapitulate cardinal features of motor neuron disease. Human Molecular Genetics, 26(4), 686-701. [DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddw429] [PMID] [PMCID]

Freischmidt, A., Schopflin, M., Feiler, M. S., Fleck, A. K., Ludolph, A. C., & Weishaupt, J. H. (2015). Profilin 1 with the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated mutation T109M displays unaltered actin binding and does not affect the actin cytoskeleton. BMC Neuroscience, 16(1), 77. [DOI:10.1186/s12868-015-0214-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

Frid, K., Einstein, O., Friedman-Levi, Y., Binyamin, O., Ben-Hur, T., & Gabizon, R. (2015). Aggregation of MBP in chronic demyelination. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, 2(7), 711-21. [DOI:10.1002/acn3.207] [PMID] [PMCID]

Harauz, G., Ladizhansky, V., & Boggs, J. M. (2009). Structural polymorphism and multifunctionality of myelin basic protein. Biochemistry, 48(34), 8094-104. [DOI:10.1021/bi901005f] [PMID]

Hardiman, O., Al-Chalabi, A., Chio, A., Corr, E. M., Logroscino, G., & Robberecht, W., et al. (2017). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 3, 17071-85. [DOI:10.1038/nrdp.2017.85] [PMID]

Ingre, C., Landers, J. E., Rizik, N., Volk, A. E., Akimoto, C., & Birve, A., et al. (2013). A novel phosphorylation site mutation in profilin 1 revealed in a large screen of US, Nordic, and German amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia cohorts. Neurobiology of Aging, 34(6), 1708-e1. [DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.009] [PMID] [PMCID]

Jockusch, B. M., Murk, K., & Rothkegel, M. (2007). The profile of profilins. Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology, 131-49. [DOI:10.1007/112_2007_704] [PMID]

Kiaei, M. (2013). New hopes and challenges for treatment of neurodegenerative disorders: Great opportunities for young neuroscientists. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 4(1), 3-4. [PMCID] [PMID]

Kiaei, M., Balasubramaniam, M., Govind Kumar, V., Shmookler Reis, R. J., Moradi, M., & Varughese, K. I. (2018). ALS-causing mutations in profilin-1 alter its conformational dynamics: A computational approach to explain propensity for aggregation. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 13102. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-31199-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680-5. [DOI:10.1038/227680a0] [PMID]

Louche, A., Salcedo, S. P., & Bigot, S. (2017). Protein-protein interactions: Pull-down assays. German: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4939-7033-9_20] [PMID]

Nekouei, M., Ghezellou, P., Aliahmadi, A., Arjmand, S., Kiaei, M., & Ghassempour, A. (2018). Changes in biophysical characteristics of PFN1 due to mutation causing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Metabolic Brain Disease, 33(6), 1975-84. [DOI:10.1007/s11011-018-0305-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

Shevchenko, A., Tomas, H., Havlis, J., Olsen, J. V., & Mann, M. (2007). In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nature Protocols, 1(6), 2856-0. [DOI:10.1038/nprot.2006.468] [PMID]

Smith, B. N., Vance, C., Scotter, E. L., Troakes, C., Wong, C. H., & Topp, S., et al. (2015). Novel mutations support a role for Profilin 1 in the pathogenesis of ALS. Neurobiology of Aging, 36(3), 1602-e17. [DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.032] [PMID] [PMCID]

Tanaka, Y., & Hasegawa, M. (2016). Profilin 1 mutants form aggregates that induce accumulation of prion-like TDP-43. Prion, 10(4), 283-9. [DOI:10.1080/19336896.2016.1207033] [PMID] [PMCID]

Tanaka, Y., Nonaka, T., Suzuki, G., Kametani, F., & Hasegawa, M. (2016). Gain-of-function profilin 1 mutations linked to familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cause seed-dependent intracellular TDP-43 aggregation. Human Molecular Genetics, 25(7), 1420-33. [DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddw024] [PMID]

Witke, W. (2004). The role of profilin complexes in cell motility and other cellular processes. Trends in Cell Biology, 14(8), 461-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.003] [PMID]

Wu, C. H., Fallini, C., Ticozzi, N., Keagle, P. J., Sapp, P. C., & Piotrowska, K., et al. (2012). Mutations in the profilin 1 gene cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature, 488(7412), 499-503. [DOI:10.1038/nature11280] [PMID] [PMCID]

Yang, C., Danielson, E. W., Qiao, T., Metterville, J., Brown, R. H., & Landers, J. E., et al. (2016). Mutant PFN1 causes ALS phenotypes and progressive motor neuron degeneration in mice by a gain of toxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(41), E6209-E6218. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1605964113] [PMID] [PMCID]

Full-Text:

1. Introduction

myotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), or motor neuron disease, also called Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disorder characterized by significant pathology and loss of upper and lower motor neurons (Hardiman et al., 2017). To initiate

the voluntary muscle movement, impulses generated from the motor cortex traveled down from upper motor neurons in the brain and lower motor nerves in the spinal cord to reach the neuromuscular junction and cross from the motor nerve to receptors on various skeletal muscles. Therefore, degeneration of motor neurons leads to muscle wasting and loss of voluntary movement (Kiaei, 2013). ALS is found to be in two types: Familial (fALS), which accounts for 10%-15% of cases, and the rest are sporadic (sALS). The etiology of fALS is associate with the mutation in the genes with varying cellular functions (Al-Chalabi, van den Berg, & Veldink, 2017). In addition to four significant genes (SOD1, FUS, TARDBP, and C9ORF72), accounting for 60-80% of fALS patients, other genes like PFN1 encoding profilin1 (PFN1) protein has been implicated in ALS (Brown & Al-Chalabi, 2017). Thus far, eight ALS-linked mutations (A20T, C71G, T109M, M114T, E117G, G118V, R136W, and Q139L) have been reported in the PFN1 protein (Chen et al., 2013; Ingre et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2012). The locations of four mutations on the actin-binding site linked to ALS are shown in Figure 1.

myotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), or motor neuron disease, also called Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disorder characterized by significant pathology and loss of upper and lower motor neurons (Hardiman et al., 2017). To initiate

the voluntary muscle movement, impulses generated from the motor cortex traveled down from upper motor neurons in the brain and lower motor nerves in the spinal cord to reach the neuromuscular junction and cross from the motor nerve to receptors on various skeletal muscles. Therefore, degeneration of motor neurons leads to muscle wasting and loss of voluntary movement (Kiaei, 2013). ALS is found to be in two types: Familial (fALS), which accounts for 10%-15% of cases, and the rest are sporadic (sALS). The etiology of fALS is associate with the mutation in the genes with varying cellular functions (Al-Chalabi, van den Berg, & Veldink, 2017). In addition to four significant genes (SOD1, FUS, TARDBP, and C9ORF72), accounting for 60-80% of fALS patients, other genes like PFN1 encoding profilin1 (PFN1) protein has been implicated in ALS (Brown & Al-Chalabi, 2017). Thus far, eight ALS-linked mutations (A20T, C71G, T109M, M114T, E117G, G118V, R136W, and Q139L) have been reported in the PFN1 protein (Chen et al., 2013; Ingre et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2012). The locations of four mutations on the actin-binding site linked to ALS are shown in Figure 1.

PFN1, a ubiquitously expressed protein in most cell and tissue types, is best known for its ability to bind G-actin via its actin-binding domain and regulate actin polymerization (Alkam, Feldman, Singh, & Kiaei, 2017). Besides being involved in cytoskeletal organization, this protein has over 50 ligands and binding partners, suggesting that it has multiple other functions. Most ligands were found to bind to PFN1 Poly-L-Proline (PLP)-binding domain, which is different from the actin-binding site. The PFN1 protein identified in various organisms is highly conserved not only in primary sequence but also in protein folding (Jockusch, Murk, & Rothkegel, 2007; Witke, 2004). Single amino acid mutation in each binding site was found to alter the secondary and tertiary structures of folded PFN1 protein that may impair the interaction of PFN1 with its ligands (Boopathy et al., 2015; Del Poggetto, Bemporad, Tatini, & Chiti, 2015; Del Poggetto, Gori, & Chiti, 2016; Nekouei et al., 2018). Moreover, these structural alterations are consistent with aggregation propensities of ALS-linked mutant PFN1 proteins studied in vivo and in vitro (Del Poggetto et al., 2018; Fil et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2016). The cytoplasmic aggregate of PFN1 can also include other functional proteins that may play critical roles in the mechanism of ALS. The protein co-aggregation may contain soluble proteins (Bondarev, Antonets, Kajava, Nizhnikov, & Zhouravleva, 2018) interacting with PFN1 by a specific binding site which may result in distinct cellular defects that contribute to the pathogenesis of motor neuron degeneration in ALS. As reported previously, PFN1 protein interacts with endogenous TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) (Tanaka, Nonaka, Suzuki, Kametani, & Hasegawa, 2016). ALS-linked mutant PFN1 may serve as inclusion bodies that initiate the formation of TDP-43 aggregates by sequestration of TDP-43 into PFN1 aggregates (positive for ubiquitin and p62) and its conversion to prion-like species, which imply the association of mutant PFN1 toxicity with TDP-43 function (Tanaka & Hasegawa, 2016; Tanaka et al., 2016).

To gain insight into the mechanism of ALS, various mouse models have been generated using some of the identified ALS causative genes, among which the most widely used is SOD1-based mouse models (Philips & Rothstein, 2015). Transgenic mouse lines overexpressing hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V produced recently (Fil et al., 2017) can also be used to study the molecular behavior of mutant PFN1 and understand its role in ALS. According to the previous studies, the G118V mutation, which is located most proximal to the actin-binding site, affects actin polymerization that may become unable to bind actin. Moreover, this mutant variant forms aggregates in vivo (neuronal cytoplasm) and in vitro (Brettle, Suchowerska, Chua, Ittner, & Fath, 2015; Fil et al., 2017; Freischmidt et al., 2015; Nekouei et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2012). Hence, this mutation can be an excellent model to study the mechanism of PFN1 neurotoxicity in ALS. In this study, we investigated the aggregation of hPFN1 protein using tissue homogenates of PFN1 mouse models by immunoblotting. The insoluble fractions of the brain and spinal cord homogenates from transgenic (hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V) and non-transgenic mice showed that only mutant PFN1 could form aggregate, not wild type and non-transgenic controls. Additionally, we expressed and purified wild type and mutant (G118V) His6-tagged PFN1 to identify additional candidate proteins in the insoluble fraction from the spinal cord by using a pull-down assay.

2. Methods

2.1. Transgenic mice

As described previously (Fil et al., 2017), transgenic (hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V) mice were generated, and the selected mice with and without ALS-like symptoms were genotyped to determine the presence of the transgene. All the animal work was approved by UAMS IACUC (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees) and carried out accordingly. Tissues used in this study were the tissue samples from mutant and wild-type PFN1 mice that were previously isolated as part of the research described in Fil et al. (2017) and were stored for further use. To analyze the expression level of hPFN1 in the tissues from these mice, brain, spinal cord, liver, and leg muscles were isolated and stored at -80°C till use. Then the frozen tissues were thawed out on the ice, and the whole brain, spinal cord, liver, and leg muscles were homogenized with RIPA buffer. After estimating protein concentration, an aliquot was mixed with sample buffer (Invitrogen), heated at 90°C for 10 min, and run on 4%-12% Bis-Tris Gel (Invitrogen). Then the separated proteins were analyzed by western blotting. Anti-PFN1 and anti-β-actin (Sigma Aldrich) were the primary antibodies followed by appropriate secondary antibodies.

2.2. Soluble and insoluble fractionation and western blotting

Previously isolated tissue samples from non-transgenic and transgenic (hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V) mice stored at -80°C as described in Fil et al. (2017) were thawed out on the ice. The motor cortex was dissected out from the whole brain. The remaining parts of the brain (referred to as the brain without motor cortex) and spinal cord were lysed for fractionation into soluble and insoluble proteins. Isolated tissues were homogenized in NP-40 lysis buffer containing (1% NP-40, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate) with EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche). The lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min and then centrifuged at 13500 rpm for 20 min at 4°C to separate the supernatant as the soluble fraction. After washing the remaining pellet twice with lysis buffer, it was resuspended in NP-40 lysis buffer plus 8 M urea/3% SDS and sonicated on ice. Further, the samples were incubated on ice for 1 hour and again centrifuged (13500 rpm, 20 min, and 4°C) to remove the supernatant as an insoluble fraction. After determining protein concentration by BCA assay, 20 µg of each sample, mixed with sample buffer (Invitrogen) with and without reducing agent, was run on 4–12% gradient NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen). The proteins separated on the SDS-PAGE were transferred to the PVDF membrane using Invitrogen iBlot device. The blotted membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS-T (0.1% Tween 20) buffer for 1 hour, and then incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibodies, including anti-PFN1 (Sigma Aldrich #P7749 and Abcam #ab50667) diluted (1:1000) in PBS-T 5% milk. After rinsing the blots with PBS-T buffer, they were incubated in HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham Corp.) for 1 hour, followed by washing with PBS-T buffer. Finally, proteins were visualized using the ECLdetection system (Amersham Corp.).

2.3. Cloning and purification of recombinant His6-tagged PFN1

Plasmid DNA constructs for human His6-tagged PFN1, both wild type (PFN1WT) and mutant (PFN1G118V), were kindly gifted by Prof. Weishaupt laboratory at the University of Ulm, Germany, as described in Freischmidt et al. (2015) (Freischmidt et al., 2015). His6-PFN1 was expressed for 4 hours upon IPTG (SinaClon) induction (1 mM) at 37°C in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen). Bacterial cells were collected and sonicated in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl and 500 mM NaCl buffer with 10 mM imidazole, pH 7.5) containing EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche). After removing the bacterial cell debris by centrifugation (11000g, 20 min), the supernatant was subjected to Ni–NTA Agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific), pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer. Recombinant His6-PFN1 was purified under native conditions in a batch mode, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Buffers containing (20 mM Tris-HCl and 500 mM NaCl) with 25 mM and 250 mM imidazole at pH 7.5 were used as wash and elution buffers, respectively. The expression and proteomic identification of recombinant His6-PFN1 proteins were assessed by SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF, as reported in our previous work (Nekouei et al., 2018).

2.4. Pull-down assay

For pull-down assay (Louche, Salcedo, & Bigot, 2017), purified His6-tagged PFN1G118V in lysis buffer was incubated with equilibrated Ni-NTA Agarose beads for 2 hours at 4°C with constant rotation. After centrifugation of flow through at 700g for 1 min, insoluble fraction of spinal cord lysate from transgenic (hPFN1G118V) mice was diluted, added to the column, and further incubated for 2 hours. Then, the beads were washed with wash buffer, and finally, interacting proteins were eluted from the column with elution buffer, as described above. To eliminate nonspecific interaction of proteins with beads, the spinal cord lysate without His6-tagged PFN1 was used as the negative control. Samples were run on 15% SDS-PAGE according to Laemmli protocol (Laemmli, 1970) and detected by Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 or silver nitrate staining.

The protein bands of interest were excised from the Coomassie blue-stained gels and digested in-gel with trypsin. Then, MALDI mass spectrometry (Applied Biosystems 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF) in positive reflector mode was used to analyze the digested proteins as described previously (Nekouei et al., 2018; Shevchenko,Tomas, Havlis, Olsen, & Mann, 2007). Before MALDI analysis, equal volumes of the resulting peptide mixtures and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix solution were thoroughly mixed, and then 1 μL of the solution was deposited on a MALDI plate. The mass analysis was followed by data processing of the monoisotopic peptide mass values of tryptic peptides using the MASCOT peptide mass fingerprinting program to identify the proteins. All reagents used in this section were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

3. Results

The transgenic mutant PFN1 mice, which we have created, developed ALS-like phenotypes and pathologies (Fil et al., 2017). Here, we have studied the effect of mutant PFN1 further. We found that hPFN1 (WT or G118V) driven by prion promoter is selectively expressed in the brain, spinal cord, and leg muscles of transgenic mice compared with non-transgenic, whereas no expression of hPFN1 was observed in the liver of these mice (Figure 2). The ALS-causing mutations in PFN1 are supposed to affect the PFN1 protein folding and 3D-structural assembly that drive the mutant PFN1 to aggregate. We have found evidence of aggregation of PFN1 in our mutant PFN1 mice and reported this initially in Fil et al. (2017). To further investigate the mechanism of PFN1 aggregation in vivo, we lysed the spinal cord, motor cortex, and brain without motor cortex of non-transgenic and transgenic (hPFN1WT and hPFN1G118V) mice with a buffer containing mild non-ionic detergent (NP-40). Western blot analysis of soluble fractions, separated from insoluble proteins by centrifugation, showed the presence of PFN1 proteins in all tissue homogenates. As shown in Figure 3A, dense bands recognized by anti-PFN1 as hPFN1 monomers are detected in the insoluble fractions of the spinal cord, motor cortex, and brain without motor cortex of mutant transgenic mice; whereas no monomeric bands of hPFN1 protein were detected in the insoluble fractions of wild type and non-transgenic controls.

Besides, we observed other bands with higher molecular weights ranging from 30-50 kDa (likely to be dimers and trimers of PFN1) in the insoluble fraction of the spinal cord compared with the insoluble fractions of the motor cortex and brain without motor cortex isolated from transgenic (hPFN1G118V) mice. These bands, along with high molecular weight species, were retained in the stacking gel (shown by an arrow), represent stable interactions against urea, detergents, and reducing agents (Figure 3A).

The soluble and insoluble fractions obtained from spinal cord homogenate were subjected to SDS-PAGE with and without reducing agent in the loading sample buffer (Figure 3B). Migration pattern based on reducing and non-reducing conditions is different and reveals new protein aggregation and complexes with PFN1. Proteins with molecular weights heavier than 40 kDa are more abundant in insoluble fractions of hPFN1G118V mice spinal cord without reducing agent vs. soluble fraction and insoluble fractions in the presence of reducing agent. We also observe smears of hPFN1G118V proteins that may indicate oligomers and represent the formation of disulfide bonds in the absence of Dithiothreitol (DTT) as a reducing agent. Interestingly, there is a difference between the blots of the two soluble fractions in the number of visible bands shown by arrows (Figure 3B).

As shown by SDS-PAGE in Figure 4A, we did not observe identical protein distributions in the soluble and insoluble fractions of the hPFN1G118V mice spinal cord. Prominent bands detected on SDS-PAGE of the insoluble fraction may be complexes of PFN1 protein and other proteins entrapped in the aggregation.

To identify what could be in the aggregate complex, we performed a pull-down assay using recombinant His6-PFN1G118V. We used a negative control column without recombinant His6-PFN1G118V to eliminate the nonspecific interacting proteins of spinal cord insoluble fraction with the affinity chromatography resin. Further, the purified Ni-NTA column again under pull-down assay condition to control for any co-purified, nonspecific host cell proteins. The arrows in Figure 3C points to PFN1-bound protein bands that are present in the eluted fraction of the sample, whereas almost none were detected in the eluted fraction of the controls. Before Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI)-Time-of-Flight (TOF) analysis of proteins, the differential protein bands were excised from the polyacrylamide gels and processed with in-gel digestion. The detected peptide masses were searched against non-redundant protein sequence databases (NCBI) using the Mascot search program. These analyses enabled us to reveal that hPFN1 is one of the proteins in the insoluble fraction which interacts with recombinant His6-PFN1G118V. These data confirm that mutant PFN1 proteins tend to interact with each other and form aggregates. Furthermore, we found that Myelin Basic Protein (MBP) is present in the complex with a score of 80 and 44% sequence coverage (Table 1).

MBP is an essential protein involved in forming and stabilizing myelin membranes in the Central Nervous System (CNS) (Boggs, 2006). Coincidentally, while searching the literature, we saw a previously published study that described that the prion-like aggregation of MBP formed during demyelination might contribute to the neurotoxicity mechanism of multiple sclerosis (Frid et al., 2015). Hence, the presence of MBP in the insoluble fraction of the ALS-linked spinal cord is of great importance and may be relevant to the loss of motor neurons in ALS.

4. Discussion

Different identified mutations located in actin- and PLP-binding sites of PFN1 protein (Figure 1) may impact various functions of PFN1, leading to ALS disease by diverse neurotoxicity mechanisms. Of those, the expression of hPFN1C71G and hPFN1G118V in two recently generated transgenic mice models displayed ALS-like phenotypes, spinal cord motor neuron degeneration, and aggregation of mutant PFN1 (Fil et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2016). As shown in Figure 2, mutant PFN1 has been primarily expressed in the CNS (brain and spinal cord) region: two major organs implicated in ALS disease.

Based on these results, we further confirmed the aggregation of mutant PFN1 and observed higher molecular weight complexes in the spinal cord, brain without motor cortex, and motor cortex tissues obtained from transgenic (hPFN1G118V) mice compared with wild type and non-transgenic mice (Figure 3). The accumulation of larger forms of PFN1 in the insoluble protein aggregate might be because of their more resistance to the degradation process. Our previous finding can support this hypothesis that a thick smear of ubiquitinated proteins larger than 50 kDa was found in the insoluble fraction of hPFN1G118V mice relative to wild type and non-transgenic (Fil et al., 2017). Our preliminary western blot analysis also revealed that mutant PFN1 form aggregate in the lumbar spinal cord was significantly higher in full-symptomatic and end-stage disease (Fil et al., 2017). These results are consistent with previous findings in vitro and in mammalian cells, confirming the aggregation tendency of mutant PFN1 relative to wild type (Alkam et al., 2017).

In this work, we have used two different anti-PFN1 antibodies, C-terminal and N-terminal, which exhibited different banding patterns (Figures 3A and B). As shown in Figure 3A, prominent bands of mutant PFN1 dimer and high molecular weight proteins were recognized by C-terminal anti-PFN1 antibody in the insoluble fraction of transgenic (hPFN1G118V) mice. This can be the consequence of conformational and structural alteration that occurred in PFN1G118V (Del Poggetto et al., 2015; Nekouei et al., 2018). Our recent in silico study reveals the impact of mutations on the amino acids near the mutation sites (Kiaei et al., 2018). We conclude that the substitution of glycine to valine enhances the hydrophobicity and the rigidity of the actin-interacting loop region. In that report, our results showed that mutant forms of PFN1 had different fluctuation patterns and salt bridges and hydrogen bond formation between critical residues, compared to wild type (Kiaei et al., 2018). Therefore, we propose that the single amino acid mutation of PFN1 (e.g. G118V) may cause ALS by losing normal function and or by the gain of toxicity. Based on our biochemical analysis of the hPFN1G118V spinal cord, different protein profiles were observed in the soluble and insoluble fractions due to the toxicity and aggregation of PFN1. The result of the pull-down assay can shed light on whether mutant PFN1 can interact with other proteins and form aggregates. Among the detected co-aggregated proteins shown in Figure 4, the bands corresponding to MBP, a critical protein in the CNS myelination, were more abundant on the silver nitrate stained gel. Based on the literature, MBP is a multifunctional protein like PFN1, which interacts in vitro with cytoskeletal proteins, including actin, and causes actin polymerization and bundling of microfilaments (Harauz, Ladizhansky, & Boggs, 2009). We recently reported that separation and vacuolization of the myelin sheath is one of the cellular abnormalities that occur in the ventral root motor axons of hPFN1G118V transgenic mice (Fil et al., 2017). Additionally, degenerating myelinated axons and glia containing phagocytized myelin were found in sciatic nerves of end-stage hPFN1G118V transgenic mice (Fil et al., 2017).

Protein aggregation is the hallmark of all neurodegenerative diseases. Thus the investigation of the aggregation of mutant PFN1 in the brain and spinal cord of the ALS mouse model may provide new clues on how PFN1 contributes to the loss of upper (corticospinal motor neurons in layer V) and lower (ventral horn) motor neurons in hPFN1G118V mice. This study suggests that the proteinopathy of mutant PFN1 maybe a critical cause of neuronal stress and death. High molecular weight bands detected with anti-PFN1 may also indicate oligomers’ formation with their PFN1 and complexes appearance with other proteins.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University Research Council.

Funding

This study was supported by the Shahid Beheshti University Research Council. This work was also supported by grants to MK from the UAMS startup fund, UAMS Center for Translational Neurosciences, NIGMS IDeA Program Award P30 GM110702, P20GM109005, and NINDS NS088653 and NS101334.

Authors' contributions

Experimental studies, data analysis, and writing – original draft: Mina Nekouei; Sub-cloning and the expression of PFN1 proteins: Atousa Aliahmadi; Supervision, writing – review & editing: Mahmoud Kiaei and Alireza Ghassempour; Conceptualization, and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Kiaei and UAMS have a financial interest in the technology discussed in this paper. These budgetary interests have been reviewed and affirmed as per the UAMS conflict of interest policies. Other authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Shahid Beheshti University Research Council for its financial support.

References

Al-Chalabi, A., van den Berg, L. H., & Veldink, J. (2017). Gene discovery in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Implications for clinical management. Nature Reviews Neurology, 13(2), 96-104. [DOI:10.1038/nrneurol.2016.182] [PMID]

Alkam, D., Feldman, E. Z., Singh, A., & Kiaei, M. (2017). Profilin1 biology and its mutation, actin(g) in disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 74(6), 967-81. [DOI:10.1007/s00018-016-2372-1] [PMID] [PMCID]

Boggs, J. (2006). Myelin basic protein: A multifunctional protein. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 63(17), 1945-61. [DOI:10.1007/s00018-006-6094-7] [PMID]

Bondarev, S., Antonets, K., Kajava, A., Nizhnikov, A., & Zhouravleva, G. (2018). Protein co-aggregation related to amyloids: methods of investigation, diversity, and classification. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(8), 2292.[DOI:10.3390/ijms19082292] [PMID] [PMCID]

Boopathy, S., Silvas, T. V., Tischbein, M., Jansen, S., Shandilya, S. M., & Zitzewitz, J. A., et al. (2015). Structural basis for mutation-induced destabilization of profilin 1 in ALS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(26), 7984-89. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1424108112] [PMID] [PMCID]

Brettle, M., Suchowerska, A. K., Chua, S. W., Ittner, L. M., & Fath, T. (2015). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated mutant profilin 1 increases dendritic arborisation and spine formation in primary hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience Letter, 609, 223-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.neulet.2015.09.034] [PMID]

Chen, Y., Zheng, Z. Z., Huang, R., Chen, K., Song, W., & Zhao, B., et al. (2013). PFN1 mutations are rare in Han Chinese populations with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiology of Aging, 34(7), 1922-e1. [DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.01.013] [PMID]

Del Poggetto, E., Bemporad, F., Tatini, F., & Chiti, F. (2015). Mutations of Profilin-1 associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis promote aggregation due to structural changes of its native state. ACS Chemical Biology, 10(11), 2553-63. [DOI:10.1021/acschembio.5b00598] [PMID]

Del Poggetto, E., Gori, L., & Chiti, F. (2016). Biophysical analysis of three novel profilin-1 variants associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis indicates a correlation between their aggregation propensity and the structural features of their globular state. Biological Chemistry, 397(9), 927-37. [DOI:10.1515/hsz-2016-0154] [PMID]

Del Poggetto, E., Toto, A., Aloise, C., Di Piro, F., Gori, L., & Malatesta, F., et al. (2018). Stability of an aggregation-prone partially folded state of human profilin-1 correlates with aggregation propensity. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 293(26), 10303-1031. [DOI:10.1074/jbc.RA118.002087] [PMID] [PMCID]

Fil, D., DeLoach, A., Yadav, S., Alkam, D., MacNicol, M., & Singh, A., et al. (2017). Mutant Profilin1 transgenic mice recapitulate cardinal features of motor neuron disease. Human Molecular Genetics, 26(4), 686-701. [DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddw429] [PMID] [PMCID]

Freischmidt, A., Schopflin, M., Feiler, M. S., Fleck, A. K., Ludolph, A. C., & Weishaupt, J. H. (2015). Profilin 1 with the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis associated mutation T109M displays unaltered actin binding and does not affect the actin cytoskeleton. BMC Neuroscience, 16(1), 77. [DOI:10.1186/s12868-015-0214-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

Frid, K., Einstein, O., Friedman-Levi, Y., Binyamin, O., Ben-Hur, T., & Gabizon, R. (2015). Aggregation of MBP in chronic demyelination. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, 2(7), 711-21. [DOI:10.1002/acn3.207] [PMID] [PMCID]

Harauz, G., Ladizhansky, V., & Boggs, J. M. (2009). Structural polymorphism and multifunctionality of myelin basic protein. Biochemistry, 48(34), 8094-104. [DOI:10.1021/bi901005f] [PMID]

Hardiman, O., Al-Chalabi, A., Chio, A., Corr, E. M., Logroscino, G., & Robberecht, W., et al. (2017). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 3, 17071-85. [DOI:10.1038/nrdp.2017.85] [PMID]

Ingre, C., Landers, J. E., Rizik, N., Volk, A. E., Akimoto, C., & Birve, A., et al. (2013). A novel phosphorylation site mutation in profilin 1 revealed in a large screen of US, Nordic, and German amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia cohorts. Neurobiology of Aging, 34(6), 1708-e1. [DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.009] [PMID] [PMCID]

Jockusch, B. M., Murk, K., & Rothkegel, M. (2007). The profile of profilins. Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology, 131-49. [DOI:10.1007/112_2007_704] [PMID]

Kiaei, M. (2013). New hopes and challenges for treatment of neurodegenerative disorders: Great opportunities for young neuroscientists. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 4(1), 3-4. [PMCID] [PMID]

Kiaei, M., Balasubramaniam, M., Govind Kumar, V., Shmookler Reis, R. J., Moradi, M., & Varughese, K. I. (2018). ALS-causing mutations in profilin-1 alter its conformational dynamics: A computational approach to explain propensity for aggregation. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 13102. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-31199-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680-5. [DOI:10.1038/227680a0] [PMID]

Louche, A., Salcedo, S. P., & Bigot, S. (2017). Protein-protein interactions: Pull-down assays. German: Springer. [DOI:10.1007/978-1-4939-7033-9_20] [PMID]

Nekouei, M., Ghezellou, P., Aliahmadi, A., Arjmand, S., Kiaei, M., & Ghassempour, A. (2018). Changes in biophysical characteristics of PFN1 due to mutation causing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Metabolic Brain Disease, 33(6), 1975-84. [DOI:10.1007/s11011-018-0305-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

Shevchenko, A., Tomas, H., Havlis, J., Olsen, J. V., & Mann, M. (2007). In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nature Protocols, 1(6), 2856-0. [DOI:10.1038/nprot.2006.468] [PMID]

Smith, B. N., Vance, C., Scotter, E. L., Troakes, C., Wong, C. H., & Topp, S., et al. (2015). Novel mutations support a role for Profilin 1 in the pathogenesis of ALS. Neurobiology of Aging, 36(3), 1602-e17. [DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.032] [PMID] [PMCID]

Tanaka, Y., & Hasegawa, M. (2016). Profilin 1 mutants form aggregates that induce accumulation of prion-like TDP-43. Prion, 10(4), 283-9. [DOI:10.1080/19336896.2016.1207033] [PMID] [PMCID]

Tanaka, Y., Nonaka, T., Suzuki, G., Kametani, F., & Hasegawa, M. (2016). Gain-of-function profilin 1 mutations linked to familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cause seed-dependent intracellular TDP-43 aggregation. Human Molecular Genetics, 25(7), 1420-33. [DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddw024] [PMID]

Witke, W. (2004). The role of profilin complexes in cell motility and other cellular processes. Trends in Cell Biology, 14(8), 461-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.tcb.2004.07.003] [PMID]

Wu, C. H., Fallini, C., Ticozzi, N., Keagle, P. J., Sapp, P. C., & Piotrowska, K., et al. (2012). Mutations in the profilin 1 gene cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature, 488(7412), 499-503. [DOI:10.1038/nature11280] [PMID] [PMCID]

Yang, C., Danielson, E. W., Qiao, T., Metterville, J., Brown, R. H., & Landers, J. E., et al. (2016). Mutant PFN1 causes ALS phenotypes and progressive motor neuron degeneration in mice by a gain of toxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(41), E6209-E6218. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1605964113] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Cellular and molecular Neuroscience

Received: 2019/12/15 | Accepted: 2020/01/23 | Published: 2021/03/1

Received: 2019/12/15 | Accepted: 2020/01/23 | Published: 2021/03/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.PNG)